Gum arabic

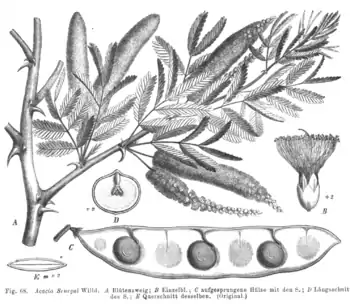

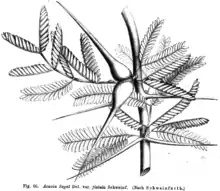

Gum arabic, also known as gum sudani, acacia gum, Arabic gum, gum acacia, acacia, Senegal gum, Indian gum, and by other names,[1] is a natural gum consisting of the hardened sap of two species of the acacia (sensu lato) tree, Acacia senegal[2] (now known as Senegalia senegal) and Vachellia (Acacia) seyal. The term "gum arabic" does not indicate a particular botanical source. In a few cases, the so-called "gum arabic" may not even have been collected from acacia species, but may originate from Combretum, Albizia, or some other genus.[1] The gum is harvested commercially from wild trees, mostly in Sudan (80%) and throughout the Sahel, from Senegal to Somalia. The name "gum Arabic" (al-samgh al-'arabi) was used in the Middle East at least as early as the 9th century. Gum arabic first found its way to Europe via Arabic ports, so retained its name.[3] Gum arabic is a complex mixture of glycoproteins and polysaccharides predominantly consisting of arabinose and galactose. It is soluble in water, edible, and used primarily in the food industry and soft-drink industry as a stabilizer, with E number E414 (I414 in the US). Gum arabic is a key ingredient in traditional lithography and is used in printing, paint production, glue, cosmetics, and various industrial applications, including viscosity control in inks and in textile industries, though less expensive materials compete with it for many of these roles.

Definition

Gum arabic was defined by the 31st Codex Committee for Food Additives, held at The Hague from 19–23 March 1999, as the dried exudate from the trunks and branches of Acacia senegal or Vachellia (Acacia) seyal in the family Fabaceae (Leguminosae).[4]:4 A 2017 safety re-evaluation by the Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) said that the term "gum arabic" does not indicate a particular botanical source; in a few cases, so‐called "gum arabic" may not even have been collected from Acacia species.[1]

Usage

Gum arabic's mixture of polysaccharides and glycoproteins gives it the properties of a glue and binder that is edible by humans. Other substances have replaced it where toxicity is not an issue, as the proportions of the various chemicals in gum arabic vary widely and make it unpredictable. Still, it remains an important ingredient in soft drink syrup and "hard" gummy candies such as gumdrops, marshmallows, and M&M's chocolate candies. For artists, it is the traditional binder in watercolor paint and in photography for gum printing, and it is used as a binder in pyrotechnic compositions. Pharmaceutical drugs and cosmetics also use the gum as a binder, emulsifying agent, and a suspending or viscosity-increasing agent.[5] Wine makers have used gum arabic as a wine fining agent.[6]

It is an important ingredient in shoe polish, and can be used in making homemade incense cones. It is also used as a lickable adhesive, for example on postage stamps, envelopes, and cigarette papers. Lithographic printers employ it to keep the non-image areas of the plate receptive to water.[7] This treatment also helps to stop oxidation of aluminium printing plates in the interval between processing of the plate and its use on a printing press.

Food

Gum arabic is used in the food industry as a stabilizer, emulsifier, and thickening agent in icing, fillings, soft candy, chewing gum, and other confectionery,[8] and to bind the sweeteners and flavorings in soft drinks.[9] A solution of sugar and gum arabic in water, gomme syrup, is sometimes used in cocktails to prevent the sugar from crystallizing and provide a smooth texture.

Gum arabic is a complex polysaccharide and soluble dietary fibre that is generally recognized as safe for human consumption. An indication of harmless flatulence occurs in some people taking large doses of 30 g or more per day.[1] It is not degraded in the intestine, but fermented in the colon under the influence of microorganisms; it is a prebiotic (as distinct from a probiotic). No regulatory or scientific consensus has been reached about its caloric value; an upper limit of 2 kcal/g was set for rats, but this is not valid for humans. The US FDA initially set a value of 4 kcal/g for food labelling, but in Europe no value was assigned for soluble dietary fibre. A 1998 review concluded that "based on present scientific knowledge, only an arbitrary value can be used for regulatory purposes".[10] In 2008, the USFDA sent a letter of no objection in response to an application to reduce the rated caloric value of gum arabic to 1.7 kcal/g.[11]

Painting and art

Gum arabic is used as a binder for watercolor painting because it dissolves easily in water. Pigment of any color is suspended within the acacia gum in varying amounts, resulting in watercolor paint. Water acts as a vehicle or a diluent to thin the watercolor paint and helps to transfer the paint to a surface such as paper. When all moisture evaporates, the acacia gum typically does not bind the pigment to the paper surface, but is totally absorbed by deeper layers.[12]

If little water is used, after evaporation, the acacia gum functions as a true binder in a paint film, increasing luminosity and helping prevent the colors from lightening. Gum arabic allows more subtle control over washes, because it facilitates the dispersion of the pigment particles. In addition, acacia gum slows evaporation of water, giving slightly longer working time.

The addition of a little gum arabic to watercolor pigment and water allows for easier lifting of pigment from paper, thus can be a useful tool when lifting out color when painting in watercolor.[12]

Ceramics

Gum arabic has a long history as additives to ceramic glazes. It acts as a binder, helping the glaze adhere to the clay before it is fired, thereby minimising damage by handling during the manufacture of the piece. As a secondary effect, it also acts as a deflocculant, increasing the fluidity of the glaze mixture, but also making it more likely to sediment out into a hard cake if not used for a while.

The gum is normally made up into a solution in hot water (typically 10–25 g/l), and then added to the glaze solution after any ball milling in concentrations from 0.02% to 3.0% of gum arabic to the dry weight of the glaze.[13] On firing, the gum burns out at a low temperature, leaving no residues in the glaze. More recently, particularly in commercial manufacturing, gum arabic is often replaced by more refined and consistent alternatives, such as carboxymethyl cellulose.

Photography

The historical photography process of gum bichromate photography uses gum arabic mixed with ammonium or potassium dichromate and pigment to create a coloured photographic emulsion that becomes relatively insoluble in water upon exposure to ultraviolet light. In the final print, the acacia gum permanently binds the pigments onto the paper.

Printmaking

Gum arabic is also used to protect and etch an image in lithographic processes, both from traditional stones and aluminum plates. In lithography, gum by itself may be used to etch very light tones, such as those made with a number-five crayon. Phosphoric, nitric, or tannic acid is added in varying concentrations to the acacia gum to etch the darker tones up to dark blacks. The etching process creates a gum adsorb layer within the matrix that attracts water, ensuring that the oil-based ink does not stick to those areas. Gum is also essential to what is sometimes called paper lithography, printing from an image created by a laser printer or photocopier.

Pyrotechnics

Gum arabic is also used as a water-soluble binder in fireworks composition.

Fuel charcoal

Gum arabic is used as a binding agent in the making of fuel charcoal. Charcoal made from the taifa plant is powdery, and so in order to form charcoal cakes, gum arabic is mixed with this powder and allowed to dry. Fuel charcoal made from taifa and gum arabic is used for cooking fires in Senegal and a few other African countries. [14]

Composition

Arabinogalactan is a biopolymer consisting of arabinose and galactose monosaccharides. It is a major component of many plant gums, including gum arabic. 8-5' Noncyclic diferulic acid has been identified as covalently linked to carbohydrate moieties of the arabinogalactan-protein fraction.[15]

Production

While gum arabic has been harvested in Arabia, Sudan, and West Asia since antiquity, sub-Saharan acacia gum has a long history as a prized export. The gum exported came from the band of acacia trees that once covered much of the Sahel region, the southern littoral of the Sahara Desert that runs from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. Today, the main populations of gum-producing Acacia species are found in Mauritania, Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. Acacia is tapped for gum by stripping bits off the bark, from which gum then exudes. Traditionally harvested by seminomadic desert pastoralists in the course of their transhumance cycle, acacia gum remains a main export of several African nations, including Mauritania, Niger, Chad, and Sudan. Total world gum arabic exports are today (2019) estimated at 160,000 tonnes, having recovered from 1987–1989 and 2003–2005 crises caused by the destruction of trees by the desert locust.

West Africa

In 1445, Prince Henry the Navigator set up a trading post on Arguin Island (off the coast of modern Mauritania), which acquired acacia gum and slaves for Portugal. With the merger of the Portuguese and Spanish crowns in 1580, the Spaniards became the dominant influence along the coast. In 1638, however, they were replaced by the Dutch, who were the first to begin exploiting the acacia gum trade. Produced by the acacia trees of Trarza and Brakna, this acacia gum was considered superior to that previously obtained in Arabia. By 1678, the French had driven out the Dutch and established a permanent settlement at Saint Louis at the mouth of the Senegal River.[16] Gum Arabic came to play an essential role in textile printing and therefore in pre-industrial economies of France, Great-Britain and other European countries. Throughout the 18th century, their competition over the commodity was so fierce, that some have spoken of gum wars.[3]

For much of the 18th and 19th centuries, gum arabic was the major export from French and British trading colonies in modern Senegal and Mauritania. West Africa had become the sole supplier of world acacia gum by the 18th century, and its export at the French colony of Saint-Louis doubled in the decade of 1830 alone. Taxes, and a threat to bypass Saint-Louis by sending gum to the British traders at Portendick, eventually brought the Emirate of Trarza into direct conflict with the French. In the 1820s, the French launched the Franco-Trarzan War of 1825. The new emir, Muhammad al Habib, had signed an agreement with the Waalo Kingdom, directly to the south of the river. In return for an end to raids in Waalo territory, the Emir took the heiress of Waalo as a bride. The prospect that Trarza might inherit control of both banks of the Senegal struck at the security of French traders, and the French responded by sending a large expeditionary force that crushed Muhammad's army. The war incited the French to expand to the north of the Senegal River for the first time, heralding French direct involvement in the interior of West Africa.[17] Africa continued to export gum arabic in large quantities—from the Sahel areas of French West Africa (modern Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger) and French Equatorial Africa (modern Chad) until these nations gained their independence in 1959–61.

Sudan

Hundreds of thousands of Sudanese are dependent on gum arabic for their livelihoods. After market reforms, Sudan's exports of gum arabic are now (2019) at about 160.000 tonnes. The production of gum arabic is heavily controlled by the Sudanese government.[18]

Pharmacology

Gum arabic slows the rate of absorption of some drugs, including amoxycillin, from the gut.[19] Nomadic populations of the Sahel and Arabia have known the beneficial effects of gum arabic for ages. In Europe, pharmaceutical applications were also among the first uses.[3]

Symbolic value

In the work of Shakespeare, Jacob Cats and many other European poets of the 13th to 17th centuries, gum arabic represented the "noble Orient". In the Sahel, it is a symbol of the purity of youth.[3]

References

- Mortensen, Alicja; Aguilar, Fernando; Crebelli, Riccardo; Di Domenico, Alessandro; Frutos, Maria Jose; Galtier, Pierre; Gott, David; Gundert‐Remy, Ursula; Lambré, Claude; Leblanc, Jean‐Charles; Lindtner, Oliver; Moldeus, Peter; Mosesso, Pasquale; Oskarsson, Agneta; Parent‐Massin, Dominique; Stankovic, Ivan; Waalkens‐Berendsen, Ine; Woutersen, Rudolf Antonius; Wright, Matthew; Younes, Maged; Brimer, Leon; Christodoulidou, Anna; Lodi, Federica; Tard, Alexandra; Dusemund, Birgit (2017). "Re‐evaluation of acacia gum (E 414) as a food additive". EFSA Journal. 15 (4): e04741. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4741. ISSN 1831-4732. PMC 7010027. PMID 32625453.

- "Acacia senegal (gum arabic)". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018.

- Dalen, van, Dorrit (2020). Gum Arabic.The Golden Tears of the Acacia Tree. Leiden: Leiden University Press. ISBN 9789087283360.

- "Production and marketing of gum arabic" (PDF). Nairobi, Kenya: Network for Natural Gums and Resins in Africa (NGARA). 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Smolinske, Susan C. (1992). Handbook of Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Excipients. p. 7. ISBN 0-8493-3585-X.

- Vivas N; Vivas de Gaulejac N; Nonier MF; Nedjma M (2001). "Effect of gum arabic on wine astringency and colloidal stability". Progres Agricole et Viticole (in French). 118 (8): 175–176. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Printing Process Explained". dynodan.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- Laura Halpin Rinsky; Glenn Rinsky (2009). The Pastry Chef's Companion: A Comprehensive Resource Guide for the Baking and Pastry Professional. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1, 134. ISBN 978-0-470-00955-0. OCLC 173182689.

- McEachran, Rich (16 August 2013). "Gum arabic: the invisible ingredient in soft drink supply chains". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Phillips, Glyn O. (1998). "Acacia gum (Gum Arabic): A nutritional fibre; metabolism and calorific value". Food Additives and Contaminants. 15 (3): 251–264. doi:10.1080/02652039809374639. ISSN 0265-203X. PMID 9666883.

- Sarah Hills (17 November 2008). "Gum arabic caloric value lowered". foodnavigator-usa. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- D. Kraaijpoel & C. Herenius. (2007) Het kunstschilderboek — handboek voor materialen en technieken, Cantecleer, p. 183

- Parmalee, Cullen W.; Harman, Cameron G. (1973). Ceramic Glazes (3rd ed.). Cahners Bookj. pp. 131–133, 145, 589. ISBN 0-8436-0609-6.

- Azzaoui, Khalil; Hammouti, B; Lamhamdi, Abdellatif; Mejdoubi, El; Berrabah, M (20 December 2014). "The Gum Arabic in the southern region of Morocco". Moroccan Journal of Chemistry. 3: 99–107.

- Renard, D; Lavenant-Gourgeon, L; Ralet, MC; Sanchez, C (2006). "Acacia senegal gum: Continuum of molecular species differing by their protein to sugar ratio, molecular weight, and charges". Biomacromolecules. 7 (9): 2637–49. doi:10.1021/bm060145j. PMID 16961328.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 482.

- Webb, James L. A. (2009). "The Trade in Gum Arabic: Prelude to French Conquest in Senegal". The Journal of African History. 26 (2–3): 149–168. doi:10.1017/S0021853700036914. JSTOR 181721.

- Gerstenzang, James; Sanders, Edmund (30 May 2007). "Impact of Bush's Sudan sanctions doubted". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 1 June 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- Eltayeb, IB; Awad, AI; Elderbi, MA; Shadad, SA (August 2004). "Effect of gum arabic on the absorption of a single oral dose of amoxicillin in healthy Sudanese volunteers". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 54 (2): 577–8. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh372. PMID 15269196.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gum arabic. |