Frenzy

Frenzy is a 1972 British thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. It is the penultimate feature film of his extensive career. The screenplay by Anthony Shaffer was based on the 1966 novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square by Arthur La Bern. The film stars Jon Finch, Alec McCowen, and Barry Foster and features Billie Whitelaw, Anna Massey, Barbara Leigh-Hunt, Bernard Cribbins and Vivien Merchant. The original music score was composed by Ron Goodwin.

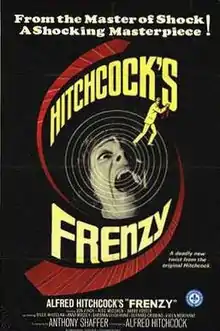

| Frenzy | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Produced by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Written by | Anthony Shaffer |

| Based on | Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square by Arthur La Bern |

| Starring | Jon Finch Alec McCowen Barry Foster |

| Music by | Ron Goodwin |

| Cinematography | Gilbert Taylor Leonard J. South |

| Edited by | John Jympson |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[1] |

| Box office | $12.6 million[2] |

The plot centres on a serial killer in contemporary London and the ex-RAF serviceman he implicates. In a very early scene there is dialogue that mentions two actual London serial murder cases: the Christie murders in the early 1950s, and the Jack the Ripper murders in 1888. Barry Foster has said that, in order to prepare for his role, he was asked by Hitchcock to study two books about Neville Heath, an English serial killer who would often pass himself off as an officer in the RAF.[3]

Frenzy was the third and final film that Hitchcock made in Britain after he moved to Hollywood in 1939. The other two were Under Capricorn in 1949 and Stage Fright in 1950 (but there were some interior and exterior scenes filmed in London for the 1956 remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much). The last film he had made in Britain before his move to America was Jamaica Inn (1939). The film was screened at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, but was not entered into the main competition.[4]

Plot

Set in the early 1970s, the plot centres on a serial killer terrorizing London by raping and then strangling women with a necktie. Bob Rusk (Barry Foster), a Covent Garden wholesale produce merchant, is the murderer. However, circumstantial evidence, partially engineered by Rusk, will implicate Rusk's friend Richard Blaney (Jon Finch), who becomes a fugitive attempting to prove his innocence.

Blaney, recently fired from his pub job, visits his ex-wife Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt) at her matchmaking business. They briefly argue, but she invites him out to dinner. Broke, Blaney ends up spending the night at a Salvation Army shelter; while there he discovers that Brenda had slipped money into his coat pocket. Soon afterward, Rusk arrives at Brenda's office. She previously refused him as a client due to his sexual peculiarities. When she spurns his advances, he rapes and strangles her with his tie. After Rusk leaves, Blaney arrives to see Brenda, only to find the office locked. Suspicion falls on Blaney after Brenda's secretary tells police that she saw Blaney leaving the building just as she was returning from lunch.

Blaney meets up with Barbara "Babs" Milligan (Anna Massey), his girlfriend and former pub co-worker. They spend the afternoon making love in a hotel that Blaney can now afford with Brenda's gift. They soon learn about Brenda's murder and that Blaney is the suspect when the afternoon paper is slipped under the door. They manage to leave the hotel by the back stairs in time to avoid the summoned police. Blaney and Babs sit in the park across the street from the hotel and try to decide what to do. There they meet Johnny Porter (Clive Swift), a friend of Blaney. He invites them up to his apartment nearby and offers to let them hide there. Johnny's wife Hetty (Billie Whitelaw) is angry at her husband for hiding Blaney, being convinced of his guilt, but Johnny offers the couple jobs in Paris.

Babs returns to the pub to fetch her and Blaney's belongings, intending to meet him the next morning to go to Paris. There, Babs runs into Rusk, who claims he is leaving town and offers her his flat for the night; after leading her there, he rapes and murders her (off-screen). Rusk hides Babs's body in a sack and stows it in the back of a lorry hauling potatoes. Back in his room, he discovers his distinctive jeweled tie pin (with the initial R) is missing, and realizes that Babs must have torn it off. Knowing the tie pin will incriminate him, Rusk goes to retrieve it, but the lorry starts off on its northern journey while he is still inside. Rigor mortis has set in, forcing Rusk to break Babs's fingers to get the pin. Disheveled and dirty, he gets out when the lorry stops at a roadside cafe. Babs's body is discovered when her leg is spotted sticking out of the back of the truck as it passes by a police car.

Blaney, now the prime suspect in Babs's murder as well as the others, seeks out Rusk's help. Although the police are actively searching Covent Garden, Rusk offers to hide Blaney at his flat. Rusk goes there first with Blaney's bag and plants Babs's belongings inside it. He then tips off the police, who arrest Blaney and find the clothing. Blaney is convicted, but he so strongly protests his innocence and accuses Rusk that Chief Inspector Oxford (Alec McCowen) reconsiders the evidence and secretly investigates Rusk. Oxford discusses the case with his wife (Vivien Merchant) in several comic relief scenes that concern her pretensions as a gourmet cook.

Blaney, now in prison, deliberately injures himself and is taken to the hospital, where his fellow inmates help him escape the locked ward. He intends to murder Rusk in revenge. Oxford, learning of Blaney's escape, suspects he is heading to Rusk's flat and immediately goes there. Blaney arrives first and finds the door unlocked. He strikes what he assumes is the sleeping Rusk with a tyre iron. However, the person in the bed is not Rusk but the corpse of his latest female victim. Oxford arrives as Blaney is standing next to the body, holding the tyre iron. He begins to proclaim his innocence, but a large banging noise coming up the staircase interrupts them. Rusk enters, dragging a large trunk into the flat. The film ends with Oxford's urbane but pointed comment "Mr. Rusk, you're not wearing your tie." Rusk drops the trunk in defeat. The credits roll in front of the trunk, with its cross motif.

Cast

- Jon Finch as Richard Ian "Dick" Blaney

- Alec McCowen as Chief Inspector Timothy Oxford

- Barry Foster as Robert "Bob" Rusk

- Billie Whitelaw as Hetty Porter

- Anna Massey as Barbara Jane "Babs" Milligan

- Barbara Leigh-Hunt as Brenda Margaret Blaney

- Bernard Cribbins as Felix Forsythe

- Vivien Merchant as Mrs. Oxford

- Michael Bates as Sergeant Spearman

- Jean Marsh as Monica Barling

- Clive Swift as Johnny Porter

- Madge Ryan as Mrs. Davison

- Elsie Randolph as Gladys

- John Boxer as Sir George

- George Tovey as Neville Salt

- Jimmy Gardner as hotel porter

- Gerald Sim as Solicitor in pub

- Noel Johnson as Doctor in pub

- Rita Webb as Mrs. Rusk (uncredited)

- Michael Sheard as Jim, Rusk's friend in pub (uncredited)

Cast notes

- Alfred Hitchcock's cameo appearance can be seen three minutes into the film in the centre of a crowd scene, wearing a bowler hat. Teaser trailers show a Hitchcock-like dummy floating in the River Thames and Hitchcock introducing the audience to Covent Garden via the fourth wall.

- Michael Caine was Hitchcock's first choice for the role of Rusk, the main antagonist, but Caine thought the character was disgusting and said "I don't want to be associated with the part." Foster was cast after Hitchcock saw him in Twisted Nerve (which featured Frenzy co-star Billie Whitelaw).

- Vanessa Redgrave reportedly turned down the role of Brenda, and Deep Red's David Hemmings (who had co-starred with Redgrave in Blowup) was considered to play Blaney.

- Helen Mirren, who later in life played Hitchcock's wife Alma Reville in Hitchcock, met with the director to discuss the role of Babs Milligan. Eventually she rejected the role, and years later said she regretted doing so.

Production

After a pair of unsuccessful films depicting political intrigue and espionage, Hitchcock returned to the murder genre with this film. The narrative makes use of the familiar Hitchcock theme of an innocent man overwhelmed by circumstantial evidence and wrongly assumed to be guilty. Some critics consider Frenzy the last great Hitchcock film and a return to form after his two previous works: Topaz and Torn Curtain.

Hitchcock announced the project in March 1968.[5]

Hitchcock approached Vladimir Nabokov to write the script, but the author turned him down because he was busy on a book. He then hired Anthony Schaffer.[6]

"It will be done comedically", said Hitchcock.[7]

The film starred relative newcomers in the lead roles. "I prefer a fresh face," he said.[8]

Shooting

Filming began in July 1971.[9]

Hitchcock set and filmed Frenzy in London after many years making films in the United States. The film opens with a sweeping shot along the Thames to Tower Bridge, and while the interior scenes were filmed at Pinewood Studios, much of the location filming was done in and around Covent Garden and was an homage to the London of Hitchcock's childhood. The son of a Covent Garden merchant, Hitchcock filmed several key scenes showing the area as the working produce market that it was. Aware that the area's days as a market were numbered, Hitchcock wanted to record the area as he remembered it. According to the 'making-of' feature on the DVD, an elderly man who remembered Hitchcock's father as a dealer in the vegetable market came to visit the set during the filming, and was treated to lunch by the director.

No. 31, Ennismore Gardens Mews, was used as the home of Brenda Margaret Blaney during the filming of Frenzy.[10]

During shooting for the film, Hitchcock's wife and longtime collaborator Alma had a stroke. As a result, some sequences were shot without Hitchcock on the set so he could tend to his wife.[11]

The film was the first Hitchcock film to have nudity (with the arguable exception of the shower scene in Psycho). There are a number of classic Hitchcock set pieces in the film, particularly the long tracking shot down the stairs when Babs is murdered. The camera moves down the stairs, out of the doorway (with a rather clever edit just after the camera exits the door which marks where the scene moves from the studio to the location footage) and across the street, where the usual activity in the market district goes on with patrons unaware that a murder is occurring in the building. A second sequence set in the back of a delivery truck full of potatoes increases the suspense, as the murderer Rusk attempts to retrieve his tie pin from the corpse of Babs. Rusk struggles with the hand and has to break the fingers of the corpse in order to retrieve his tie pin and try to escape unseen from the truck.[12]

The part of London shown in the film still exists more or less intact, but the fruit and vegetable market no longer operates from that site, having relocated in 1974. The buildings seen in the film are now occupied by banks and legal offices, restaurants and nightclubs, such as Henrietta Street, where Rusk lived (and Babs met her untimely demise). Oxford Street, which had the back alley (Dryden Chambers, now demolished) leading to Brenda Blaney's matrimonial agency, is the busiest shopping area in Britain. Nell of Old Drury, which is the public house where the doctor and solicitor had their frank, plot-assisting discussion on sex killers, is still a thriving bar. The lanes where merchants and workers once carried their produce, as seen in the film, are now occupied by tourists and street performers.

Novelist La Bern later expressed his dissatisfaction with Shaffer's adaptation of his book.[13]

Soundtrack

Henry Mancini originally was hired as the film's composer. "If the same film was made ten years ago it would've had twice the amount of music in it", he said.[14]

His opening theme was written in Bachian organ andante, opening in D minor, for organ and an orchestra of strings and brass, and was intended to express the formality of the grey London landmarks, but Hitchcock thought it sounded too much like Bernard Herrmann's scores. According to Mancini, "Hitchcock came to the recording session, listened awhile and said 'Look, if I want Herrmann, I'd ask for Herrmann.'" After an enigmatic, behind-the-scenes melodrama, the composer was fired. He never understood the experience, insisting that his score sounded nothing like Herrmann's work. Mancini had to pay all transportation and accommodations himself. In his autobiography, Mancini reports that the discussions between himself and Hitchcock seemed clear, and he thought he understood what was wanted; but he was replaced and flew back home to Hollywood. The irony was that Mancini was being second-guessed for being too dark and symphonic after having been criticized for being too light before. Mancini's experience with Frenzy was a painful topic for the composer for years to come.

Hitchcock then hired composer Ron Goodwin to write the score after being impressed with some of his earlier work. He had Goodwin rescore the opening titles in the style of a London travelogue - the director had heard his score for the Peter Sellers sketch Balham, Gateway to the South.[15] Goodwin's music had a lighter tone in the opening scenes, and scenes featuring London scenery, while there were darker undertones in certain other scenes.

Reception

Frenzy received positive reviews from critics. Vincent Canby of [he New York Times called it "a passionately entertaining film" with "a marvelously funny script" and a "superb" cast.[16] He put it on his year-end list of the ten best films of 1972.[17] Variety also posted a rave review, declaring: "Ingeniously fresh story-telling ideas, stamped with the same mischievous, audacious and often outrageous mixture of humor and suspense that first made him and later sustained him, make the Universal release one of Hitchcock's major achievements."[18] Roger Ebert gave the film his highest grade of four stars, calling it "a return to old forms by the master of suspense, whose newer forms have pleased movie critics but not his public. This is the kind of thriller Hitchcock was making in the 1940s, filled with macabre details, incongruous humor, and the desperation of a man convicted of a crime he didn't commit."[19] Penelope Gilliatt of The New Yorker wrote of Hitchcock that "we are nearly back in the days of his great English films", adding "He is lucky to have been able to draw on Anthony Shaffer to do Frenzy's sly screenplay, not to speak of a cast of first-rate, well-equated actors pretty much unknown outside England, so that audiences have no preconceptions about who are the stars and therefore unkillable."[20] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called the film "Alfred Hitchcock's best picture in years, with "all the marks of work by a master at his craft and at his most assured."[21]

Some reviews were more mixed. Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote that the film "has a promising opening sequence and a witty curtain line, but the material in between is decidedly pedestrian. The reviewers who've been hailing 'Frenzy' as a new classic and the triumphant return of the master of suspense are, to put it kindly, exaggerating the occasion ... If this picture had been made by anyone else, it would be described, justly, as a mildly diverting attempt to imitate Hitchcock."[22] The Monthly Film Bulletin was unsure what to make of the picture, noting an "old-fashioned air" to it that seemed to suggest that Hitchcock's return to England "signalled a regression to an almost pre-war style of filmmaking." It concluded: "For all its apparent awkwardness of script and characterisation (Jon Finch especially can make little of Shaffer's anemically written hero) there is enough in Frenzy to suggest that, after the routine critical dismissals, it will repay serious assessment."[23]

Frenzy ranked 14th on Variety's list of the Big Rental Films of 1972, with rentals of $6.3 million in the United States and Canada.[24]

The film was the subject of the 2012 book Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece by Raymond Foery.[25] Frenzy currently holds an 87% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 31 reviews. The critical consensus reads: "Marking Alfred Hitchcock's return to England and first foray into viscerally explicit carnage, Frenzy finds the master of horror regaining his grip on the audience's pulse -- and making their blood run cold."[26] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 92 out of 100 based on 15 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[27]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Alfred Hitchcock | Nominated |

| Best Director | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay | Anthony Shaffer | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Ron Goodwin | Nominated | |

References

- Nat Segaloff, Final Cuts: The Last Films of 50 Great Directors, Bear Manor Media 2013 p 131

- "Frenzy, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- Osteen, Mark; Williams, Tony (2014). Hitchcock and Adaptation: On the Page and Screen. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 169. ISBN 9781442230880. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Festival de Cannes: Frenzy". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- It's Psycho Time Again for Hitchcock. By A.H. WEILER. The New York Times, 31 March 1968: D15.

- THE EYEHOLE OF KNOWLEDGE. Appel, Alfred, Jr. Film Comment; New York Vol. 9, Iss. 3 (May/June 1973): 20-26.

- "What's It All About, Alfie?" Champlin, Charles. Los Angeles Times, 2 June 1971: f1.

- 'I Tried to Be Discreet With That Nude Corpse'. By Guy Flatley. The New York Times, 18 June 1972: D13.

- "Beth Brickell in Star Role". Murphy, Mary. Los Angeles Times, 24 July 1971: a7.

- Mews News. Issue 32. Lurot Brand. Published winter 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- McGilligan, Patrick (30 September 2003). Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books.

- Wood, Robin, Hitchcock's Films Revisited. Columbia University Press, 2002

- "Letters to the Editor: Hitchcock's "Frenzy", The Times, 29 May 1972". Hitchcockwiki.com. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Henry Mancini: 'people who regard film composers as whores are merely snobs'". The Guardian, 29 December 1971: 9.

- Alexander Gleason (11 January 2003). "Obituary: Ron Goodwin". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Canby, Vincent (22 June 1972). "'Frenzy,' Hitchcock in Dazzling Form". The New York Times: 48.

- Canby, Vincent (31 December 1972). "Critic's Choice — Ten Best Films of '72". The New York Times: D1.

- "Frenzy". Variety: 6. 31 May 1972.

- Ebert, Roger. "Frenzy". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Gilliatt, Penelope (24 June 1972). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 52.

- Thomas, Kevin (June 25, 1972). "Hitchcock's Best Picture in Years -- 'Frenzy'". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 22.

- Arnold, Gary (23 June 1972). "'Frenzy': The Thrill Is Gone". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- "Frenzy". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 39 (461): 113. June 1972.

- "Big Rental Films of 1972". Variety. 3 January 1973. p. 7.

- Foery, Raymond (2012). Alfred Hitchcock's Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7756-6.

- Frenzy, retrieved 6 March 2018

- "Frenzy". Metacritic.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frenzy |