Fulshear, Texas

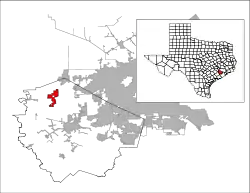

Fulshear (/ˈfʊlʃər/ FUUL-shər)[5] is a city in northwest Fort Bend County, Texas, and is located on the western edge of the Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land metropolitan area.

Fulshear, Texas | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): "Fort Bend County's Premier Address" | |

Location of Fulshear, Texas | |

| Coordinates: 29°41′27″N 95°53′26″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Fort Bend |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.06 sq mi (28.65 km2) |

| • Land | 11.01 sq mi (28.52 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.14 km2) |

| Elevation | 131 ft (40 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 408 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 13,914 |

| • Density | 1,263.76/sq mi (487.92/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 77441 |

| Area code(s) | 281, 832, 713, 346 |

| FIPS code | 48-27876[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1336299[4] |

| Website | www |

History

Before the Texas Independence

The history of Fulshear is closely intertwined with the historical events leading up to Texas Independence and eventual statehood within the United States of America. The small agricultural community traces its origins to the arrival of Churchill Fulshear, one of Stephen F. Austin's original Old Three Hundred.[6][7] He moved from Tennessee to Texas in the summer of 1824 with his wife, Betsy Summers, daughter, Mary, and three sons, Benjamin, Graves, and Churchill Fulshear, Jr.[8]

As a man with considerable wealth and property, Churchill Fulshear Sr. obtained on July 16, 1824 a land grant from the Mexican government and Stephen F. Austin that allowed him and his family to settle in Austin's colony.[9][10] He established a slave plantation that raised cotton, corn, rice, pecans and livestock. Churchill Fulshear Sr. died on January 18, 1831 with the plantation ownership passed onto his youngest son, Churchill Fulshear, Jr.,[8] who added a cotton gin and flour mill which flourished well into the late 1880s.[9][11]

During the Texas Revolution, Churchill Jr. and his two brothers, Graves and Benjamin, served as scouts for the Texan army as the Mexican army under the command of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna pursued Sam Houston's army and civilians who fled after Santa Anna's victory at the 1836 Battle of the Alamo. The Fulshear area was on the route of both the Mexicans and the Texan soldiers. Churchill and his brothers scouted Santa Anna's army as they crossed the Brazos River near their plantation on April 14, 1836.[11]

According to one account, the Texan army trying to prevent Santa Anna and the Mexican army from crossing the Brazos River camped on the Fulshear plantation. They retreated when they learned that:

1,500 Mexican soldiers had crossed nearby at Thompson's Ferry, they, too, had to retreat. Randolph Foster was one of the Old 300 settlers whose plantation was in the John Foster grant that lay between what is now FM 359 and FM 723 just south of Fulshear. He was a member of Martin's Company and, from William Harris Wharton's account, we ascertain that the Company "camped on the night of the 11th at Churchill Fulshear's." Churchill Fulshear's plantation lay on the north side of the Brazos River in what is now Fulshear township.[12]

Texas Independence to the early 1900s

In the years after Texas Independence, Churchill Jr. expanded the plantation and commercial interests. This included a horse race track called "Churchill Downs" (not the same as the present-day Churchill Downs, which is in Kentucky) that he operated during the 1850s to 1870s in Pittsville, Texas, located several miles north of Fulsher. One of the most famous horses bred by Churchill Jr. was "Get-A-Way" (known as "Old Get"), which raced on numerous tracks throughout the United States and Europe.[10] He also actively sold and purchased real estate, including the 654 acres sold to John Randon on May 10, 1844 for $4,000.[10]

The old tombstones in the Fulshear Cemetery (previously called Union Chapel Cemetery Grounds) identify the names of some of the original pioneers who settled the Fulshear area: Andrews, Avery, Avis, Bains, Bond, Boone, Brasell, Bulwinkel, Cooper, Davis, Dozier, Edmonson, Everett, Gibson, Foster, Harris, Holmes, Hoskins, Huggins, Hunter, Jager, Kemp, Lovelace, Mayes, McElwee, McJunkin, McLeod, Miller, Nesbitt, Parker, Patton, Quinn, Rowles, Sass, Shieve, Sheriff, Simonton, Sparks, Thompson, Utley, Wade, Walker, Wilson, Wimberly, and Winner.[13]

Mention must be made of several men who made outstanding contributions to the Fulshear community and who are buried in this cemetery. They are: (l) Randolph Foster - an "Old 300" Settler of the area, (2) Rev. John Patton - the first Methodist Minister connected to Union Chappel, and (3) Dr. Robert Locke Harris - a Confederate War Surgeon who visited after the War in 1865 and remained to become a prominent doctor of the area.[13][14]

A significant historical development occurred in 1888 when Churchill Jr. granted the San Antonio and Aransas Pass (SA & AP) Railroad (SA&AP) the right of way through his plantation.[15][16][17] The town of Fulshear grew around the railroad in the 1890s, a period that also saw the demise of other local communities which, like Pittsville, had rejected the SA & AP Railroad the right of way on their lands.[16]

Churchill Fulshear Jr. died in 1892.[11] In the same year, the Southern Pacific Railroad gained ownership of the SA & AP Railroad.[17] In the decades following, the town established a public school district (1893), a Methodist Church (1894) and business establishments that included a barber shop, doctor, drug store, blacksmith, saloon, hotel, and post office.[18]

A Texas Historical Marker located in downtown Fulshear succinctly summarizes its 19th Century history:

On July 16, 1824, land grant of Mexico to Churchill Fulshear, one of the "Old 300" settlers of Stephen F. Austin, father of Texas. Churchill Fulshear, Jr., veteran of Texas War for Independence, built 4-story brick mansion in 1850s, bred and raced horses at Churchill Downs (at Pittsville, 2 mi. N). His pupil, John Huggins, won world fame by training first American horse to win the English Derby. Town platted here 1890 by San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railroad, soon was trade center, with many facilities. The Rev. J. H. Holt was first (1894) pastor of the still existant Methodist church.[19]

Civil War, slavery and sharecropping

While few historical records exist on the Civil War and the people of Fulshear, there are accounts that local landowners, surgeons, and commercial business men actively supported and enrolled in the Confederate Army during the US Civil War.[18]

Two of the three active Fulshear cemeteries provide insights into the history of the non-white racial minorities.[20] As was common practice prior to the US Civil War, plantation owners like Churchill Fulshear would build separate cemeteries based on race. In addition to farm labor, "Churchill Fulshear's slaves were put to work making the bricks for the Fulshear plantation mansion, called Lake Hill."[21] Since the mid-1800s, minority families were buried either in the Fulshear Black Cemetery or the Fulshear Spanish Cemetery, which were originally part of the Fulshear family plantation.[22] This includes many of the black sharecroppers who worked the land after the end of slavery in the United States. A Texas Historical Marker here gives the historical information of the Black Cemetery:

Oral tradition says that this cemetery begin as a slave cemetery on the plantation of Tennessee native Churchill Fulshear. Many early burials are unmarked, and the oldest headstone is that of Rebecca Scott in 1915. In addition, midwives, a chef, a horse trainer and cowboy, the first colored school house founders, business men and women, two local entrepreneurs, religious leaders, and veterans from WWI to the Vietnam War are buried here. The rural landscape of the rolling hills and trees surrounding a variety of headstones made of fieldstone, granite, marble, steel, homemade concrete, wood and resin. The cemetery is evidence of the rich heritage of the people in this area. Historic Texas Cemetery - 2010[23]

After the abolition of slavery with defeat of the Confederacy, many of the emancipated slaves became sharecroppers, which meant they rented land to farm it. Many grew cotton and potatoes, and supplemented their livelihood by raising chickens, eggs, and pigs as well as helping other farmers pick beans, potatoes, and peanuts.[24] Many of these sharecroppers are buried in the Fulshear Black Cemetery. In 1995, Fulshear Mayor Viola Randle won a class-action lawsuit to legally define the Fulshear Black Cemetery as belonging to the Fulshear Black Cemetery Association and to prevent an attempt by a local property owner to restrict more burials in the cemetery.[24]

The Spanish Cemetery, which was often referred to as the "Catholic Cemetery," is just south of the Fulshear Cemetery and an estimated 300 grave sites.[25]

Like elsewhere in Texas and the American South, the schools segregated based on race. The original "white-only" school house was built in 1893 that was later expanded into a two-story building in 1912.[26] The segregated school for Mexican students was located nearby. Two "black-only" school houses were built in rural areas several miles to the south and northwest of town.[26] These Fulshear schools were merged into the Lamar Consolidated Independent School District in 1948.[27]

Boom and bust, 1900s–1970s

By 1898 a thriving population of 250 residents supported eleven stores, three saloons, a school and a hotel. A block of businesses was destroyed by a fire in 1910 but the town recovered quickly and soon downtown consisted of several general stores, a drug store, a doctor's office, a post office, a millinery shop, three churches, an undertaker's supply store, a depot, a grist mill, a cotton gin, a blacksmith shop, a barber shop, six saloons, four schools, a boarding house, a hotel and a local telephone system. On Saturdays, when the local hands were paid, Fulshear was so busy that residents complained that the sidewalks were too crowded to walk on. The town had 300 residents and ten stores in 1929. But the population fell to 100 in 1933, around the time that the Fulshear plantation house was torn down. The Depression and a changed lifestyle caused residents to leave Fulshear. Fulshear did her share toward the war effort during WWII. Not only did she contribute men and women for the armed forces and war industries but an airplane lookout station was also manned daily on the roof of one of the brick buildings.[28]

Fulshear remained a rural agricultural town with population ranging from 300 to 700 into the 1970s.[29]

Incorporated city, 1977–present

The city was incorporated in 1977.[30] The town served as a marketing center for locally produced rice, cotton, soybeans, corn, poultry, sorghum, pecan, horses and cattle. Growth in Fulshear exploded in the 2000s due to its proximity to Houston.[31] Around 2008 the community had around 700 residents. In October 2013 the population went over 5,000. By that time, traffic was commonplace while historically it had not been.[32] In May 2017, Fulshear was listed the richest small town in Texas[33] on MSN.com.

Geography

Fulshear is located in northern Fort Bend County at 29°41′27″N 95°53′26″W (29.690824, -95.890531).[34]

The city is 50 miles inland from the Gulf Coast. April, October and November are the most pleasant months in Fulshear, while August and July are the least comfortable months. Sediments deposited over time from the Brazos River has created rich soil and many native trees grow in the area, including oak, cottonwood, ash, and pecan. The growing season is very long (296 days) thanks to the county's geographical proximity to the Gulf of Mexico, and temperatures are mild year-round.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.15 square miles (21.12 km2), of which 8.09 square miles (20.95 km2) are land and 0.066 square miles (0.17 km2), or 0.79%, is covered by water.[35]

It is located at the intersection of Farm to Market Road 359 and Farm to Market Road 1093.[30] Downtown Houston is 33 miles (53 km) to the east, and Wallis is 15 miles (24 km) to the west. Interstate 10 at Brookshire is 7 miles (11 km) to the north.

Fulshear has an extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ) of 37.11 square miles (96.1 km2). Of the general law cities in Texas, Fulshear has one of the largest ETJs.[30]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 2019 (est.) | 13,914 | [2] | |

Fulshear, TX is home to a population of 6.2k people, from which 90.8% are citizens. As of 2017, 16.6% of Fulshear, TX residents were born outside of the country (1.03k people). The ethnic composition of the population of Fulshear, TX is composed of 3.87k White Alone residents (62.5%), 940 Hispanic or Latino residents (15.2%), 733 Asian Alone residents (11.8%), 350 Black or African American Alone residents (5.64%), 288 Two or More Races residents (4.64%), 15 Some Other Race Alone residents (0.242%), 3 American Indian & Alaska Native Alone residents (0.0484%), and 0 Native Hawaiian & Other Pacific Islander Alone residents (0%).[37]

In 2017, the most common birthplace for the foreign-born residents of Texas was Mexico, the natal country of 2,547,886 Texas residents, followed by India with 231,271 and El Salvador with 200,904.[37] The median household income in Fulshear, TX is $174,194. Males in Fulshear, TX have an average income that is 1.41 times higher than the average income of females, which is $45,959. The income inequality in Fulshear, TX (measured using the Gini index) is 0.482, which is higher than the national average.[38] From 2016 to 2017, employment in Fulshear, TX grew at a rate of 35.6%, from 1.99k employees to 2.7k employees. The most common job groups, by number of people living in Fulshear, TX, are Management Occupations (675 people), Sales & Related Occupations (356 people), and Business & Financial Operations Occupations (243 people).[38]

View south on FM 359 toward signal at FM 1093

View south on FM 359 toward signal at FM 1093 Wildflowers on Winner-Foster Road south of Fulshear

Wildflowers on Winner-Foster Road south of Fulshear

Government and infrastructure

Fulshear is incorporated as a general law city. As of 2015 the taxation rate is 0.161631% per $100 valuation. Of the taxation rates in Fort Bend County, Fulshear's is among the lowest.[30]

Mayor Aaron Groff was elected mayor in 2018 after serving two years as a member of the Fulshear Development Corporation, the City's Type B Economic Development Sales Tax Corporation.[39]

| Office | Office Holder |

|---|---|

| Mayor | Aaron Groff |

| Mayor Pro Tem | Kaye Kahlich |

| At-large Position 1 | Kent Pool |

| At-large Position 2 | John Kelly |

| District 1 | Kevin White |

| District 2 | Debra Cates |

| District 3 | Lisa Kettler Martin |

| District 4 | Joel M. Patterson |

Postal service

The United States Postal Service operates the Fulshear Post Office at 8055 Farm to Market Road 359 South.[40]

Public libraries

Fulshear's Bob Lutts Fulshear/Simonton Branch Library is a part of the Fort Bend County Libraries system. The branch, which opened in May 1998, was the third branch built with 1989 bond funds. The land currently occupied by the library was previously the Fort Bend County Precinct 4 headquarters. Bob Lutts, the precinct commissioner, offered the land to the library system. The Fulshear City Council asked the county to name the library after Lutts. The library is now within Precinct 3.[41]

Fulshear City Hall on FM 1093

Fulshear City Hall on FM 1093 Fire Station No. 1 on 5th Street

Fire Station No. 1 on 5th Street Bob Lutts Library on FM 359

Bob Lutts Library on FM 359 US Post Office on FM 359 in Fulshear

US Post Office on FM 359 in Fulshear

Education

Public schools

Fulshear is zoned to schools in the Lamar Consolidated Independent School District (LCISD) and the Katy Independent School District (KISD) in separate portions.

LCISD portion

- The LCISD portion is served by:

- Huggins Elementary School (Fulshear) - The elementary school is named after John Huggins who won world fame by training the first horse to win the English Derby.[42]

- Leaman Junior High School (Unincorporated Fort Bend County) - The junior high school is named after Dean Leaman, the owner of Allied Concrete.[43]

- Fulshear High School (Unincorporated Fort Bend County) - The high school is named after the city founder, Churchill Fulshear Jr

Dean Leaman Junior High School

Dean Leaman Junior High School Huggins Elementary School

Huggins Elementary School

Katy ISD portion

The Katy ISD portion is served by:

- James Randolph Elementary (Fulshear)

- Seven Lakes Junior High School (Unincorporated Fort Bend County- Cinco Ranch/Seven Meadows area)

- Obra Tompkins High School (Unincorporated Fort Bend County- Cinco Ranch/Kings Lake/Silver Ranch area)

- Jordan High School (opening 2020)

Private schools

As of 2019 the British International School of Houston in Greater Katy has a school bus service to Fulshear.[44]

Transportation

Airports near Fulshear, located in unincorporated Fort Bend County, include Westheimer Air Park, Cardiff Brothers Airport, and Dewberry Heliport.

Area airports with commercial airline service include George Bush Intercontinental Airport and William P. Hobby Airport, both of which are in Houston.

Arts and culture

In 2011, the Fulshear Art Council (FAC), a non-profit 501c3 organization, was created to encourage and support the arts and arts education in Fulshear and the surrounding areas.[45] The council began showcasing local artists and their artwork at events hosted in downtown Fulshear. These showcases now occur the first Tuesday of the month and are referred to as Arts and Drafts events. FAC changed its name to Arts Fulshear in 2012, and the organization began providing art and theater classes to local youth. In 2013, Arts Fulshear added adult art classes, and it began hosting the annual Fulshear Art Walk.

Documentaries

The documentary The Heart of Texas was filmed partly in Fulshear.

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "How to Pronounce: F Cities". Texastripper.com. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- Churchill Fulshear

- "Old 300 and Austin's Colony | Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)". tshaonline.org. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Crawford, Ann (June 12, 2010). "Fulshear, Churchill". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Nguyen, Dianna (July 10, 2017). "Celebrating Churchill Fulshear, Jr". Fort Bend Herald. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- CROCKETT, TERRY (2020). "Churchill Fulshear Jr -His Land, His Family, His Home and His Legacy". Explore Texas. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "Fulshear, Churchill, Jr Yes". Handbook of Texas. November 5, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- STRICKLAND, Susan (July 2017). "Fulshear in the Path of Texas History" (PDF). Fulshear Magazine. 03: 38–41.

- Wendt, Billie (2013). "FULSHEAR CEMETERY". Fort Bend County. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Randolph Foster

- San Antonio and Aransas Pass (SA & AP) Railroad

- "Fulshear, Pittsville and the one decision that completely changed their futures". Fort Bend Museum. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- McJunkin, Daniel (February 4, 2019). "A Tale of Two Cities: Fulshear's Turning Point". Issuu. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- "Details - Pittsville - Atlas Number 5507016356 - Atlas: Texas Historical Commission". atlas.thc.texas.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "Details - Town of Fulshear - Atlas Number 5157008998 - Atlas: Texas Historical Commission". atlas.thc.state.tx.us. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Fulshear cemeteries

- Fort Bend County. Fulshear Black Cemetery.

- Brust, Amelia (October 25, 2017). "Historic Fulshear ethnic cemeteries are families' link to the past". impact. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "Details - Fulshear Black Cemetery - Atlas Number 5507017257 - Atlas: Texas Historical Commission". atlas.thc.state.tx.us. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Strickland, Susan (March 27, 2018). "Grande Dame of Fushear Viola Gilmore Randle". Fulshear Magazine. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- McJunkin, Daniel (March 30, 2017). "Fulshear Area Cemeteries". Fulshear Magazine. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Strickland, Susan. "Fulshear Magazine Volume 2 - Number 2". issuu. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Home to a Proud Past". www.fulsheartexas.gov. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Home to a Proud Past". www.fulsheartexas.gov. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Fulshear, Pittsville and the one decision that completely changed their futures". Fort Bend Museum. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "City Demographics." City of Fulshear. Retrieved on November 6, 2011.

- "The city is moving to the country Archived 2007-09-09 at the Wayback Machine." KHOU-TV. April 6, 2007. Retrieved on December 4, 2008.

- Mulvaney, Erin. "Fulshear growing pains hit ballot." Houston Chronicle. November 3, 2013. Retrieved on April 7, 2014.

- https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/realestate/the-richest-town-in-every-state/ar-BBBddkD?li=AA4Zjn#image=BBBdhy8%7C2

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Fulshear city, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- "Fulshear, TX | Data USA". datausa.io. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Fulshear, TX | Data USA". datausa.io. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- City of Fulshear

- "Post Office Location - FULSHEAR Archived 2010-07-01 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 14, 2010.

- "Bob Lutts Fulshear/Simonton Branch Library." Fort Bend County Libraries. Retrieved on May 14, 2010.

- "Town of Fulshear". Texas Historical Markers. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Dolan, Betsy. "Lamar Consolidated ISD chooses names for new schools Archived 2014-04-08 at the Wayback Machine." Fort Bend Star. June 27, 2012. Retrieved on April 7, 2014.

- "School Bus Transportation". British International School of Houston. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- "Arts Fulshear" Retrieved on April 21, 2014

Further reading

- "City of Fulshear Update" (Archive), Fort Bend Economic Development Council.

- "FULSHEAR, TX," Handbook of Texas Online, Ann Fears Crawford, accessed April 26, 2020.

- Fulshear Black Cemetery, Fort Bend County

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fulshear, Texas. |

- Official website

- Fulshear, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online