Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti (/ˌdɒnɪˈzɛti/,[1] also UK: /-ɪtˈsɛti/,[2] US: /ˌdoʊn-, -ɪdˈzɛti/,[3] Italian: [doˈmeːniko ɡaeˈtaːno maˈriːa donidˈdzetti] (![]() listen); 29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, Donizetti was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style during the first half of the nineteenth century. Donizetti's close association with the bel canto style was undoubtedly an influence on other composers such as Giuseppe Verdi.[4] Donizetti was born in Bergamo in Lombardy. Although he did not come from a musical background, at an early age he was taken under the wing of composer Simon Mayr[5] who had enrolled him by means of a full scholarship in a school which he had set up. There he received detailed training in the arts of fugue and counterpoint. Mayr was also instrumental in obtaining a place for the young man at the Bologna Academy, where, at the age of 19,[6] he wrote his first one-act opera, the comedy Il Pigmalione, which may never have been performed during his lifetime.[7]

listen); 29 November 1797 – 8 April 1848) was an Italian composer, best known for his almost 70 operas. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, Donizetti was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style during the first half of the nineteenth century. Donizetti's close association with the bel canto style was undoubtedly an influence on other composers such as Giuseppe Verdi.[4] Donizetti was born in Bergamo in Lombardy. Although he did not come from a musical background, at an early age he was taken under the wing of composer Simon Mayr[5] who had enrolled him by means of a full scholarship in a school which he had set up. There he received detailed training in the arts of fugue and counterpoint. Mayr was also instrumental in obtaining a place for the young man at the Bologna Academy, where, at the age of 19,[6] he wrote his first one-act opera, the comedy Il Pigmalione, which may never have been performed during his lifetime.[7]

.jpg.webp)

An offer in 1822 from Domenico Barbaja, the impresario of the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, which followed the composer's ninth opera, led to his move to that city and his residency there which lasted until the production of Caterina Cornaro in January 1844.[8] In all, Naples presented 51 of Donizetti's operas.[8] Before 1830, success came primarily with his comic operas, the serious ones failing to attract significant audiences.[9] However, his first notable success came with an opera seria, Zoraida di Granata, which was presented in 1822 in Rome. In 1830, when Anna Bolena was premiered, Donizetti made a major impact on the Italian and international opera scene and this shifted the balance of success away from primarily comedic operas,[9] although even after that date, his best-known works included comedies such as L'elisir d'amore (1832) and Don Pasquale (1843). Significant historical dramas did appear and succeed; they included Lucia di Lammermoor (the first to have a libretto written by Salvadore Cammarano) given in Naples in 1835, and one of the most successful Neapolitan operas, Roberto Devereux in 1837.[10] Up to that point, all of his operas had been set to Italian libretti.

Donizetti found himself increasingly chafing against the censorship limitations which existed in Italy (and especially in Naples). From about 1836, he became interested in working in Paris, where he saw much greater freedom to choose subject matter,[11] in addition to receiving larger fees and greater prestige. Starting in 1838 with an offer from the Paris Opéra for two new works, he spent a considerable part of the following ten years in that city, and set several operas to French texts as well as overseeing staging of his Italian works. The first opera was a French version of the then-unperformed Poliuto which, in April 1840, was revised to become Les martyrs. Two new operas were also given in Paris at that time. As the 1840s progressed, Donizetti moved regularly between Naples, Rome, Paris, and Vienna, continuing to compose and stage his own operas as well as those of other composers. But from around 1843, severe illness began to take hold and to limit his activities. Eventually, by early 1846 he was obliged to be confined to an institution for the mentally ill and, by late 1847, friends had him moved back to Bergamo, where he died in a state of mental derangement due to neurosyphilis in April 1848.[12]

Early life and musical education in Bergamo and Bologna

The youngest of three sons, Donizetti was born in 1797 in Bergamo's Borgo Canale quarter, located just outside the city walls. His family was very poor and had no tradition of music, his father Andrea being the caretaker of the town pawnshop. Simone Mayr, a German composer of internationally successful operas, had become maestro di cappella at Bergamo's principal church in 1802. He founded the Lezioni Caritatevoli school in Bergamo in 1805 for the purpose of providing musical training, including classes in literature, beyond what choirboys ordinarily received up until the time that their voices broke. In 1807, Andrea Donizetti attempted to enroll both his sons, but the elder, Giuseppe (then 18), was considered too old. Gaetano (then 9) was accepted.[13]

While not especially successful as a choirboy during the first three trial months of 1807 (there being some concern about a difetto di gola, a throat defect), Mayr was soon reporting that Gaetano "surpasses all the others in musical progress"[14] and he was able to persuade the authorities that the young boy's talents were worthy of keeping him in the school. He remained there for nine years, until 1815.

However, as Donizetti scholar William Ashbrook notes, in 1809 he was threatened with having to leave because his voice was changing. In 1810 he applied for and was accepted by the local art school, the Academia Carrara, but it is not known whether he attended classes. Then, in 1811, Mayr once again intervened. Having written both libretto and music for a "pasticcio-farsa", Il piccolo compositore di musica, as the final concert of the academic year, Mayr cast five young students, among them his young pupil Donizetti as "the little composer". As Ashbrook states, this "was nothing less than Mayr's argument that Donizetti be allowed to continue his musical studies".[15]

The piece was performed on 13 September 1811 and included the composer character stating the following:

Ah, by Bacchus, with this aria / I'll have universal applause. / They'll say to me, "Bravo, Maestro! / I, with a sufficiently modest air, / Will go around with my head bent... / I’ll have eulogies in the newspaper / I know how to make myself immortal.[16]

In reply to the chiding which comes from the other four characters in the piece after the "little composer" 's boasts, in the drama the "composer" responds with:

I have a vast mind, swift talent, ready fantasy—and I'm a thunderbolt at composing.[16]

The performance also included a waltz which Donizetti played and for which he received credit in the libretto.[17] In singing this piece, all five young men were given opportunities to show off their musical knowledge and talent.

The following two years were somewhat precarious for the young Donizetti: the 16-year-old created quite a reputation for what he did do—which is regularly to fail to attend classes—and also for what he did instead, which as to make something of a spectacle of himself in the town.[18]

However, in spite of all this, Mayr not only persuaded Gaetano's parents to allow him to continue studies, but also secured funding from the Congregazione di Carità in Bergamo for two years of scholarships. In addition, he provided the young musician with letters of recommendation to both the publisher Giovanni Ricordi as well as to the Marchese Francesco Sampieri in Bologna (who would find him suitable lodging) and where, at the Liceo Musicale, he was given the opportunity to study musical structure under the renowned Padre Stanislao Mattei.[18]

In Bologna, he would justify the faith which Mayr had placed in him. Author John Stewart Allitt describes his 1816 "initial exercises in operatic style",[19] the opera Il pigmalione, as well as his composition of portions of Olympiade and L'ira d'Achille in 1817, as no more than "suggest[ing] the work of a student".[19] Encouraged by Mayr to return to Bergamo in 1817, he began his "quartet years" as well as composing piano pieces and, most likely, being a performing member of quartets where he would have also heard music of other composers.[19] In addition, he began seeking employment.

Career as an opera composer

1818–1822: Early compositions

After extending his time in Bologna for as long as he could, Donizetti was forced to return to Bergamo since no other prospects appeared. Various small opportunities came his way and, at the same time, he made the acquaintance of several of the singers appearing during the 1817/18 Carnival season. Among them was the soprano Giuseppina Ronzi de Begnis and her husband, the bass Giuseppe de Begnis.[20]

A coincidental meeting around April 1818 with an old school friend, Bartolomeo Merelli (who was to go on to a distinguished career), led to an offer to compose the music from a libretto which became Enrico di Borgogna. Without a commission from any opera house, Donizetti decided to write the music first and then try to find a company to accept it. He was able to do so when Paolo Zancla, the impresario of the Teatro San Luca (an early theatre built in 1629, which later became the Teatro Goldoni) in Venice accepted it. Thus Enrico was presented on 14 November 1818, but with little success, the audience appearing to be more interested in the newly re-decorated opera house rather than the performances, which suffered from the last-minute withdrawal of the soprano Adelaide Catalani due to stage fright and the consequent omission of some her music. Musicologist and Donizetti scholar William Ashbrook provides a quotation from a review in the Nuovo osservatore veneziano of 17 November in which the reviewer notes some of these performance issues which faced the composer, but he adds: "one cannot but recognize a regular handling and expressive quality in his style. For these the public wanted to salute Signor Donizetti on stage at the end of the opera."[21]

For Donizetti, the result was a further commission and, using another of Merelli's librettos, this became the one-act, Una follia which was presented a month later. However, with no other work forthcoming, the composer once again returned to Bergamo, where a cast of singers made up from the Venice production the month before, presented Enrico di Borgogna in his home town on 26 December.[22] He spent the early months of 1819 working on some sacred and instrumental music, but little else came of his efforts until the latter part of the year when he wrote Il falegname di Livonia from a libretto by Gherardo Bevilacqua-Aldobrandini. The opera was given first at the Teatro San Samuele in Venice in December. Other work included expansion of Le nozze in villa, a project which he had started in mid-1819, but the opera was not presented until the carnival season of 1820/21 in Mantua. Little is known about it except its lack of success and the fact that the score has totally disappeared.[23]

Success in Rome

After these minor compositions under the commission of Paolo Zancla, Donizetti retreated to Bergamo once again to examine how he could make his career move along. From the point of view of Donizetti's evolving style, Ashbrook states that, in order to please the opera-going public in the first quarter of the 19th century, it was necessary to cater to their tastes, to make a major impression at the first performance (otherwise there would be no others), and to emulate the preferred musical style of the day, that of Rossini whose music "was the public's yardstick when they were assessing new scores".[23]

Remaining in Bergamo until October 1821, the composer busied himself with a variety of instrumental and choral pieces, but during that year, he had been in negotiation with Giovanni Paterni, intendant of the Teatro Argentina in Rome, and by 17 June had received a contract to compose another opera from a libretto being prepared by Merelli. It is unclear as to how this connection came about: whether it had been at Merelli's suggestion or whether, as William Ashbrook speculates, it had been Mayr who had initially been approached by Paterni to write the opera but who, due to advancing age, had recommended his prize pupil.[24] This new opera seria became Donizetti's Zoraida di Granata, his ninth work. The libretto had been started by August and, between then and 1 October, when Donizetti was provided with a letter of introduction from Mayr to Jacopo Ferretti, the Roman poet and librettist who was later to feature in the young composer's career, much of the music had been composed.[25]

The twenty-four-year-old composer arrived in Rome on 21 October, but plans for staging the opera were plagued with a major problem: the tenor cast in the major role died a few days before the opening night on 28 January 1822 and the role had to be re-written for a musico, a mezzo-soprano singing a male role, a not uncommon feature of the era and of Rossini's operas. Opening night was a triumph for Donizetti; as reported in the weekly Notizie del giorno:

A new and very happy hope is rising for the Italian musical theatre. The young Maestro Gaetano Donizetti...has launched himself strongly in his truly serious opera, Zoraida. Unanimous, sincere, universal was the applause he justly collected from the capacity audience....[26]

Donizetti moves to Naples

Soon after 19 February, Donizetti left Rome for Naples, where he was to settle for a large part of his life. It appears that he had asked Mayr for a letter of introduction,[27] but his fame had preceded him for, on 28th, the announcement of the summer season at the Teatro Nuovo in the Giornale del Regno delle Due Sicilie stated that it would include a Donizetti opera, describing the composer as:

a young pupil of one of the most valued Maestros of the century, Mayer (sic), a large part of whose glory might be called ours, he having modeled his style on that of the great luminaries of the musical art sprung up among us. [His opera in Rome] was accepted with the most flattering applause.[28]

News of this work impressed Domenico Barbaja, the prominent Intendant of the Teatro San Carlo and other royal houses in the city such as the smaller Teatro Nuovo and the Teatro del Fondo. By late March Donizetti had been offered a contract not only to compose new operas, but also to be responsible for preparing performances of new productions by other composers whose work had been given elsewhere.[29] On 12 May the first new opera, La zingara, was given at the Nuovo "with hot enthusiasm", as scholar Herbert Weinstock states.[27]

It ran for 28 consecutive evenings, followed by 20 more in July, receiving high praise in the Giornale.[29] One of the later performances became the occasion for Donizetti to meet the then-21-year-old music student, Vincenzo Bellini, an event recounted by Francesco Florimo some sixty years later.[30] ' The second new work, which appeared six weeks later on 29 June, was a one-act farsa, La lettera anonima. Ashbrook's comments—which reinforce those of the Giornali critic who reviewed the work on 1 July[31]—recognize an important aspect of Donizetti's burgeoning musical style: [he shows that] "his concern with the dramatic essence of opera rather than the mechanical working out of musical formulas was, even at this early stage, was already present and active."[32]

Late July 1822 to February 1824: Assignments in Milan and Rome

On 3 August for what would become Chiara e Serafina, ossia I pirati, Donizetti entered into a contract with librettist Felice Romani, but he was over-committed and unable to deliver anything until 3 October. The premiere had been scheduled for only about three weeks away and, due to the delays and illnesses among the cast members, it did not receive good reviews, although it did receive a respectable 12 performances.

Returning north via Rome, Donizetti signed a contract for performances of Zoraida by the Teatro Argentina which included the requirement that the libretto to be revised by Ferretti, given Donizetti's low opinion of the work of the original Neapolitan librettist, Andrea Leone Tottola: he referred to it as "a great barking".[33] In addition to the revision, he committed to write another new opera for the Rome's Teatro Valle which would also be set to a libretto written by Ferretti. Donizetti finally returned to Naples by late March.[34]

Immediately busy in the spring months of 1823 with a cantata, an opera seria for the San Carlo, and an opera buffa for the Nuovo, Donizetti also had to work on the revised Zoraide for Rome. Unfortunately however, the music set for the San Carlo premiere of Alfredo il grande on 2 July was described in the Giornali as "...one could not recognize the composer of La zingara." It received only one performance, while his two-act farsa, Il fortunato inganno, given in September at the Teatro del Fondo, received only three performances.

In October and for the remainder of the year, he was back in Rome, where he spent time adding five new pieces to Zoraida, which was performed at the Teatro Argentina on 7 January 1824. However, this version was less successful than the original. The second opera for Rome's Teatro Valle also had a libretto by Ferretti, one which has since been regarded as one of his best.[35] It was the opera buffa L'ajo nell'imbarazzo (The Tutor Embarrassed), the premiere of which took place on 4 February 1824 and "was greeted with wild enthusiasm [and] it was with this opera that [...] Donizetti had his first really lasting success."[36] Allitt notes that with a good libretto to hand, "Donizetti never failed its dramatic content" and he adds that "Donizetti had a far better sense of what would succeed on the stage than his librettists."[37]

1824–1830: Palermo and Naples

Back in Naples, he embarked upon his first venture into English Romanticism[37] with the opera semiseria, Emilia di Liverpool, which was given only seven performances in July 1824 at the Nuovo. The critical reaction in the Giornali some months later focused on the weaknesses of the semiseria genre itself, although it did describe Donizetti's music for Emilia as "pretty".[38] The composer's activities in Naples became limited because 1825 was a Holy Year in Rome and the death of Ferdinand I in Naples caused little or no opera to be produced in either city for a considerable time.

However, he did obtain a year-long position for the 1825/26 season at the Teatro Carolino in Palermo, where he became musical director (as well teaching at the Conservatory).[39] There, he staged his 1824 version of L'ajo nell'imbarazzo as well as his new opera Alahor in Granata. But overall, his experience in Palermo does not appear to have been pleasant, mainly because of the poorly managed theatre, the continual indisposition of singers, or their failure to appear on time. These issues caused a delay until January 1827 for the premiere of Alahor, after which he went back in Naples in February, but with no specific commitments until midsummer.[40]

That summer was to see the successful presentations at the Teatro Nuovo of the adapted version of L'ajo nell'imbarazzo given as Don Gregorio and, a month later, a one-act melodramma or opera, Elvida, a pièce d'occasion for the birthday of Queen Maria of the Two Sicilies, which contained some florid music for the tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini; but it only received three performances.[41]

Writer John Stewart Allitt observes that, by 1827/28, three important elements in Donizetti's professional and personal life came together: Firstly, he met and began to work with the librettist Domenico Gilardoni, who wrote eleven librettos for him, beginning with Otto mesi in due ore in 1827 and continuing until 1833. Gilardoni shared with the composer a very good sense of what would work on stage.[42] Next, the Naples impresario Barbaja engaged him to write twelve new operas during the following three years.[42] In addition, he was to be appointed to the position of Director of the Royal Theatres of Naples beginning in 1829, a job that the composer accepted and held until 1838. Like Rossini, who had occupied this position before him, Donizetti was free to compose for other opera houses. Finally, in May 1827 he announced his engagement to Virginia Vasselli, the then 18-year-old daughter of the Roman family who had befriended him there.[42]

The couple were married in July 1828 and immediately settled in a new home in Naples. Within two months he had written another opera semiseria, Gianni di Calais, from a libretto by Gilardoni. It was their fourth collaboration, and became a success not only in Naples but also in Rome over the 1830/31 season. Writing about the Naples premiere, the correspondent of the Gazzetta privilegiata di Milano stated: "The situations that the libretto offers are truly ingenious and do honour to the poet, Gilardoni. Maestro Donizetti has known how to take advantage of them...",[43] thus reaffirming the growing dramatic skills displayed by the young composer.

1830–1838: International fame

(posthumous portrait by Ponziano Loverini)

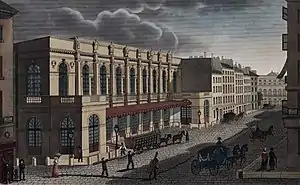

In 1830, Donizetti scored his most acclaimed and his first international success with Anna Bolena, given at the Teatro Carcano in Milan on 26 December 1830 with Giuditta Pasta in the title role. Also, the acclaimed tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini appeared in the role of Percy. With this opera, Donizetti achieved instant fame throughout Europe. Performances were staged "up and down the Italian peninsula" between 1830 and 1834 and then throughout Europe's capitals well into the 1840s, with revivals being presented up to about 1881.[44] London was the first European capital to see the work; it was given at the King's Theatre on 8 July 1831.

In regard to which operatic form Donizetti was to have the greater success, when the semi-seria work of 1828, Gianni di Calais, was given in Rome very soon after Anna Bolena had appeared, the Gazzetta privilegiata di Milano described the relationship between the two forms of opera and concluded that "in two classes—tragic and comic—very close together...the former wins incomparably over the latter".[43] This appears to have solidified Donizetti's reputation as a composer of successful serious opera, although other comedies were to appear quite quickly.

With his commissions, the years from 1830 to 1835 saw a huge outpouring of work; L'elisir d'amore, a comedy produced in 1832, came soon after Anna Bolena's success and is deemed to be one of the masterpieces of 19th-century opera buffa.

Then came a rapid series of operas from Naples including Francesca di Foix (May 1831); La romanziera e l'uomo nero (June 1831); and Fausta (January 1832). Two new operas were presented in Milan: Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali (April 1831) and Ugo, conte di Parigi (March 1832). Rome presented Il furioso all'isola di San Domingo (January 1833) and Torquato Tasso (September 1833). Otto mesi in due ore (1833) was given in Livorno and Parisina (March 1833) was given in Florence.

After the successful staging of Lucrezia Borgia in 1833, his reputation was further consolidated, and Donizetti followed the paths of both Rossini and Bellini by visiting Paris, where his Marin Faliero was given at the Théâtre-Italien in March 1835. However, it suffered by comparison to Bellini's I puritani which appeared at the same time.

Donizetti returned from Paris to oversee the staging of Lucia di Lammermoor on 26 September 1835. It was set to a libretto by Salvadore Cammarano, the first of eight for the composer. The opera was based on The Bride of Lammermoor, the novel by Sir Walter Scott,[45] and it was to become his most famous opera, one of the high points of the bel canto tradition, the opera reaching a stature similar to that achieved by Bellini's Norma.

This dramma tragico appeared at a time when several factors were moving Donizetti's reputation as a composer of opera to greater heights: Gioachino Rossini had recently retired and Vincenzo Bellini had died shortly before the premiere of Lucia leaving Donizetti as "the sole reigning genius of Italian opera".[46] Not only were conditions ripe for Donizetti to achieve greater fame as a composer, but there was also an interest across the continent of Europe in the history and culture of Scotland. The perceived romance of its violent wars and feuds, as well as its folklore and mythology, intrigued 19th century readers and audiences,[46] and Scott made use of these stereotypes in his novel.

At the same time, continental audiences of that time seemed to be fascinated by the Tudor period of 16th century English history, revolving as it does around the lives of King Henry VIII (and his six wives), Mary I of England ("Bloody Mary"), Queen Elizabeth I, as well as the doomed Mary Stuart, known in England as Mary, Queen of Scots. Many of these historical characters appear in Donizetti's dramas, operas which both preceded and followed Anna Bolena. They were Elisabetta al castello di Kenilworth, based on Scribe's Leicester and Hugo's Amy Robsart (given in Naples in July 1829 and revised in 1830). Then came Maria Stuarda (Mary Stuart), based on Schiller's play and given at La Scala in December 1835. It was followed by the third in the "Three Donizetti Queens" series, Roberto Devereux, which features the relationship between Elizabeth and the Earl of Essex. It was given at the San Carlo in Naples in October 1837.

As Donizetti's fame grew, so did his engagements. He was offered commissions by both La Fenice in Venice—a house he had not visited for about seventeen years and to which he returned to present Belisario on 4 February 1836. Just as importantly, after the success of his Lucia at the Théâtre-Italien in Paris in December 1837, approaches came from the Paris Opéra. As musicologists Roger Parker and William Ashbrook have stated, "negotiations with Charles Duponchel, the director of the Opéra, took on a positive note for the first time"[47] and "the road to Paris lay open for him",[48] the first Italian to obtain a commission to write a real grand opera.[49]

1838–1840: Donizetti abandons Naples for Paris

In October 1838, Donizetti moved to Paris vowing never to have dealings with the San Carlo again after the King of Naples banned the production of Poliuto on the grounds that such a sacred subject was inappropriate for the stage. In Paris, he offered Poliuto to the Opéra and it was set to a new and expanded four-act French-language libretto by Eugène Scribe with the title, Les Martyrs. Performed in April 1840, it was his first grand opera in the French tradition and was quite successful. Before leaving that city in June 1840, he had time to oversee the translation of Lucia di Lammermoor into Lucie de Lammermoor as well as to write La fille du régiment, his first opera written specifically to a French libretto. This became another success.

1840–1843: Back and forth between Paris, Milan, Vienna, and Naples

After leaving Paris in June 1840, Donizetti was to write ten new operas, although not all were performed in his lifetime. Before arriving in Milan by August 1840, he visited Switzerland and then his hometown of Bergamo, eventually reaching Milan where he was to prepare an Italian version of La fille du régiment. No sooner was that accomplished than he was back in Paris to adapt the never-performed 1839 libretto L'Ange de Nisida as the French-language La favorite, the premiere of which took place on 2 December 1840. Then he rushed back to Milan for Christmas, but returned almost immediately and by late February 1841 was preparing a new opera, Rita, ou Deux hommes et une femme. However, it was not staged until 1860.[50]

Donizetti returned once more to Milan where he stayed with the accommodating Giuseppina Appiano Stringeli with whom he had a pleasant time. Unwilling to leave Milan,[51] but encouraged to return to Paris by Michele Accursi (with whom the composer was to be involved in Paris in 1843), he oversaw the December production of Maria Padilla at La Scala, and began writing Linda di Chamounix in preparation for March 1842 travels to Vienna, in which city he had been engaged by the royal court.

During this time and prior to leaving for Vienna, he was persuaded to conduct the premiere of Rossini's Stabat Mater in Bologna in March 1842. Friends—including his brother-in-law, Antonio Vasselli (known as Totò)—continually attempted to persuade him to take up an academic position in Bologna rather than the Vienna court engagement, if for no other reason that it would give the composer a base from which to work and teach and not be continually exhausting himself with travel between cities. But in a letter to Vasselli, he adamantly refused.[52]

When Donizetti went to Bologna for the Stabat Mater, Rossini attended the third performance, and the two men—each former students of the Bologna Conservatory—met for the first time, with Rossini declaring that Donizetti was "the only maestro in Italy capable of conducting my Stabat as I would have it".[53]

Arriving in Vienna in the Spring of 1842 with a letter of recommendation from Rossini, Donizetti became involved in rehearsals for Linda di Chamounix which was given its premiere in May and which was a huge success. In addition, he was appointed kapellmeister to the chapel of the royal court, the same post which had been held by Mozart.

He left Vienna on 1 July 1842 after the Spring Italian season, travelling to Milan, Bergamo (in order to see the now-aging Mayr, but where the deterioration of his own health became more apparent[54]), and then on to Naples in August, a city he had not visited since 1838. A contract with the San Carlo remained unresolved. Also, it appears that he wished to sell his Naples house, but could not bring himself to go through with it, such was the sorrow which remained after his wife's death in 1837.[55]

However, on 6 September he was on his way back to Genoa from where he would leave for a three-month planned stay in Paris to be followed by time in Vienna once again. He wrote that he would work on translations of Maria Padilla and Linda di Chamounix and "God knows what else I'll do".[56] During the time in Naples, his poor health was again a problem causing him to remain in bed for days at a time.

Arriving once again in Paris in late September 1842, he accomplished the revisions to the two Italian operas and he received a suggestion from Jules Janin, the newly appointed director of the Théâtre-Italien, that he might compose a new opera for that house.[57] Janin's idea was that it should be a new opera buffa and tailored to the talents of some major singers including Giulia Grisi, Antonio Tamburini, and Luigi Lablache who had been hired.[57] The result turned out to be the comic opera, Don Pasquale, planned for January 1843. While preparations were underway, other ideas came to Donizetti and, discovering Cammarano's libretto for Giuseppe Lillo's unsuccessful 1839 Il Conte di Chalais, he turned it into the first two acts of Maria di Rohan within twenty-four hours. Another opera with Scribe as librettist was in the works: it was to be Dom Sébastien, roi de Portugal planned for November 1843 in Paris.[58]

When Don Pasquale was presented on 3 January, it was an overwhelming success with performances continuing until late March. Writing in the Journal des débats on 6 January, the critic Étienne-Jean Delécluze proclaimed:

No opera composed expressly for the Théâtre-Italien has had a more clamorous success. Four or five numbers repeated, callings-out of the singers, callings-out of the Maestro—in sum, one of those ovations.....which in Paris are reserved for the truly great.[59]

1843–1845: Paris to Vienna to Italy; final return to Paris

By 1843, Donizetti was exhibiting symptoms of syphilis and probable bipolar disorder: "the inner man was broken, sad, and incurably sick", states Allitt.[60] Ashbrook observes that the preoccupation with work which obsessed Donizetti in the last months of 1842 and throughout 1843 "suggests that he recognised what was wrong with him and that he wanted to compose as much as he could while he was still able"[61] But after the success in Paris, he continued working and left once again for Vienna, arriving there by mid-January 1843.

Shortly thereafter, he wrote to Antonio Vasselli outlining his plans for that year, concluding with the somewhat ominous: "All of this with a new illness contracted in Paris, which has still not passed and for which I am awaiting your prescription"[62] But, in the body of the letter, he lays out what he will be aiming to accomplish in 1843: in Vienna, a French drama; in Naples, a planned Ruy-Blas [but it was never composed]; in Paris for the Opéra-Comique, "a Flemish subject", and for the Opéra, "I am using a Portuguese subject in five acts" (which was to be Dom Sébastien, Roi de Portugal, and actually given on 13 November.) Finally, he adds "and first I am remounting Les Martyrs which is creating a furor in the provinces".[62]

However, by early February, he is already writing via an intermediary to Vincenzo Flauto, then the impresario at the San Carlo in Naples, in an attempt to break his agreement to compose for that house in July. He was increasingly becoming aware of the limitations which his poor health is imposing upon him. As it turned out, he was able to revive a half-completed work which had been started for Vienna, but only after receiving a rejection to his request to be released from his Naples' obligations did he work on finishing Caterina Cornaro by May for a production in Naples in January 1844, but without the composer being present. When it did appear, it was not very successful. As far as the work for the Opéra-Comique was concerned—Ne m'oubliez moi it was to be called—it appears that he was able to break his contract with that house, although he had already composed and orchestrated seven numbers.[61]

Work in Vienna

Donizetti's obligations in Vienna included overseeing the annual Italian season at the Theater am Kärntnertor which began in May. Verdi's Nabucco (which Donizetti had seen in Milan at its premiere in March 1842 and with which he had been impressed) was featured as part of that season. However, his main preoccupation was to complete the orchestration of Maria di Rohan, which was accomplished by 13 February for planned performances in June. The season began with a very successful revival of Linda di Chamounix. Nabucco followed, the first production of a Verdi opera in Vienna. The season also included Don Pasquale in addition to The Barber of Seville.[63] Finally, Maria di Rohan was given on 5 June. In reporting the reaction to this opera in a teasing letter to Antonio Vasselli in Rome, he tried to build suspense, stating that "With the utmost sorrow, I must announce to you that last evening I have given my Maria di Rohan [and he names the singers]. All their talent was not enough to save me from "a sea of [pause, space] – applause....Everything went well. Everything."[63]

Return to Paris

Returning to Paris as quickly as possible, Donizetti left Vienna around 11 July 1843 in his newly purchased carriage and arrived on about 20th, immediately getting down to work on finishing Dom Sébastien, which he describes as a massive enterprise: "what a staggering spectacle.....I am terribly wearied by this enormous opera in five acts which carries bags full of music for singing and dancing."[64] It is his longest opera as well as the one on which he spent the most time.

With rehearsals in progress at the Opéra for Dom Sébastien, the first performance being planned for 13 November, the composer was also working on readying Maria di Rohan for the Théâtre-Italien on the following evening, 14 November. Both were successful, although author Herbert Weinstock states that "the older opera was an immediate, unquestioned success with both audience and critics". However, Maria di Rohan continued for 33 performances in all,[65] whereas Dom Sébastien remained in the repertory until 1845 with a total of 32 performances.

1844: In Vienna

On 30 December 1843, Donizetti was back in Vienna, having delayed leaving until the 20th because of illness. Ashbrook comments on how he was viewed in that city, with "friends notic[ing] an alarming change in his physical condition",[66] and with his ability to concentrate and simply to remaining standing often being impaired.

Having entered into a contract with Léon Pillet of the Opéra for a new work for the coming year, he found nothing to be suitable and immediately wrote to Pillet proposing that another composer take his place. While waiting to see if he could be relieved from writing a large-scale work if Mayerbeer would allow Le Prophète to be staged instead that autumn, he looked forward to the arrival of his brother from Turkey in May and to the prospect of their traveling to Italy together that summer. Eventually, it was agreed that his commitment to the Opéra could be postponed until November 1845.[67]

While taking care of some of his obligations to the Viennese court, for the remainder of the month he awaited news on the outcome of the 12 January premiere of Caterina Cornaro in Naples. By the 31st (or 1 February), he learned the truth: it had been a failure.[68] What was worse were the rumours that it was not in fact Donizetti's work, although a report from Guido Zavadini suggested that it was probably a combination of elements which caused the failure, including the singers' difficulty in finding the right tone in the absence of the maestro, plus the heavily censored libretto.[69] Primarily, however, the opera's failure appears to have been due to the maestro's absence, because he was unable to be present to oversee and control the staging, normally one of Donizetti's strengths.[70]

The Italian season in Vienna, which included Bellini's Norma and revivals of Linda di Chamounix and of Don Pasquale, also included the first production there of Verdi's Ernani. Donizetti had made a promise to Giacomo Pedroni of the publishing house Casa Ricordi to oversee the production of the opera, which was given on 30 May with Donizetti conducting. The result was a very warm letter from Giuseppe Verdi entrusting the production to his care; it concluded: "With the most profound esteem, your most devoted servant, G. Verdi".[71]

Summer/Autumn 1844: Travel to and within Italy

Gaetano's brother Giuseppe, on leave from Constantinople, arrived in Vienna in early June. He had intended to leave by about 22nd, but Gaetano's bout of illness delayed his departure, and the brothers traveled together to Bergamo on about 12 or 13 July proceeding slowly but arriving around the 21st.

William Ashbrook describes the second half of 1844 as a period of "pathetic restlessness". He continues: "Donizetti went to Bergamo, Lovere on Lake Iseo [about 26 miles from Bergamo], back to Bergamo, to Milan [31 July], to Genoa [with his friend Antonio Dolci, on 3 August, where they stayed until 10 August because of illness], to Naples [by steamer, from which he wrote to Vasselli in Rome explaining that the upcoming visit may be last time he would see his brother], [then] to Rome [on 14 September to see Vasselli], back to Naples [on 2 October after being invited back to Naples for the first San Carlo performances of Maria di Rohan on 11 November, which was immensely successful], to Genoa [on 14 November by boat; arrived on the 19th] and on to Milan again [for two days]"[72] before reaching Bergamo on 23 November where his found his old friend Mayr to be very ill. He delayed his departure for as long as possible, but Mayr died on 2 December shortly after Donizetti had left Bergamo.

December 1844 – July 1845: Last visit to Vienna

By 5 December he was in Vienna writing a letter to his friend Guglielmo Cottrau on 6th and again on 12th, stating "I am not well. I am in the hands of a doctor."[73] While there were periods of relative calm, his health continued to fail him periodically and then there were relapses into depression, as expressed in a letter: "I am half-destroyed, it's a miracle that I'm still on my feet".[73]

Writing to unnamed Paris friends on 7 February, even after the very positive reaction received at the premiere of a specially-prepared Dom Sébastien on 6 February 1845 (which he had conducted for three performances of the total of 162 given over the following years until 1884),[74] he grumbles about the reactions of the Parisian audiences and continues with a brief report on his health which, he says, "if it is no better and this continues, I'll find myself forced to go to spend some months resting in Bergamo."[74] At the same time, he rejected offers to compose, one offer coming from London and requiring an opera four months away; the objection of having limited time was given. Other appeals came from Paris, one directly from Vatel, the new impresario of the Théâtre-Italien, who traveled to Vienna to see the composer. As other biographers also note, there is an increasing sense that, during 1845, Donizetti became more and more aware of the real state of his health and the limitations it has begun to impose on his activities.[74] Other letters into April and May reveal much of the same, and the fact that he did not attend the opening performance of Verdi's I due Foscari on 3 April, finally seeing it only at its fourth performance, confirms that.

By the end of May, no decision as what to do or where to go had been made, but—finally—he decided on Paris where he would claim a forfeit from the Opéra for the non-production of Le duc d'Albe, his unfulfilled second commission from 1840 which, although still unfinished, had a completed libretto. He left Vienna for the last time on 10 July 1845.

1845–1848: Return to Paris; declining health; return to Bergamo; death

By the time he reached Paris, Donizetti had been suffering from malaises, headaches, and nausea for decades, but had never been formally treated. In early August, he initiated a lawsuit against the Opéra which dragged on until April 1846 and in which he prevailed.

The culmination of the crisis in Donizetti's health came in August 1845 when he was diagnosed with cerebro-spinal syphilis and severe mental illness. Two doctors, including Dr. Philippe Ricord (a specialist in syphilis), recommended that, along with various remedies, he abandon work altogether and both agreed that the Italian climate would be better for his health. But letters to friends reveal two things: that he continued to work on Gemma di Vergy that autumn for its performance in Paris on 16 December, and that he revealed a lot about the progression of his illness.[75]

As his condition worsened, the composer's brother Giuseppe dispatched his son Andrea to Paris from Constantinople. Arriving there on 25 December, Andrea lodged at the Hôtel Manchester with his uncle, but immediately consulted Dr. Ricord on his uncle's condition. Ricord recorded his opinion in mid-January that, while it ultimately might be better for the composer's health for him to be in Italy, it was not advisable for him to travel until the spring. Consulting two additional doctors as well as Dr. Ricord, Andrea received their written opinion after an examination on 28 January 1846. In summary, it stated that the doctors "believe that M. Donizetti no longer is capable of calculating sanely the significance of his decisions".[76]

Institutionalization

In February 1846, reluctant to consider going further towards institutionalization, he relied on the further advice of two of the doctors who had examined his uncle in late January. They stated:

We....certify that M. Gaetan (sic) Donizetti is the victim of a mental disease that brings disorder into his actions and his decisions; that it is to be desired in the interest of his preservation and his treatment that he be isolated in an establishment devoted to cerebral and intellectual maladies.[77]

Therefore, Andrea agreed to allow his uncle to be taken to a facility which has been described as "resemb[ling] that of a health spa.... with a central hospital more-or-less in the guise of a country house"[78] and Donizetti left Paris by coach with Andrea, believing that they were travelling to Vienna, where he was due by 12 February to fulfill his contract. Following behind in another coach was Dr. Ricord. After three hours they arrived at the Maison Esquirol in Ivry-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris,[79] where an explanation involving an accident was concocted to explain the need to spend the night at a "comfortable inn".[78] Within a few days—realizing that he was being confined—Donizetti wrote urgent letters seeking help from friends, but they were never delivered. However, evidence provided from friends who visited Donizetti over the following months, states that he was being treated very well, the facility having a reputation for the care given to its patients.[78] Various aggressive treatments were tried, and were described as having their "successes, however fleeting".[78]

By the end of May, Andrea had decided that his uncle would be better off in the Italian climate, and three outside physicians were called in for their opinions. Their report concluded with the advice that he leave for Italy without delay.[80] But, as Andrea began to make plans for his uncle's journey to and upkeep in Bergamo, he was forced by the Paris Prefect of Police to have his uncle undergo another examination by other physicians appointed by the Prefect. Their conclusion was the opposite of that of the previous doctors: "we are of the opinion that the trip should be forbidden formally as offering very real dangers and being far from allowing hope of any useful result."[81] With that, the Prefect informed Andrea that Donizetti could not be moved from Ivry. Andrea saw little use in remaining in Paris. He sought a final opinion from the three doctors practicing at the clinic, and on 30 August, they provided a lengthy report outlining step-by-step the complete physical condition of their declining patient, concluding that the rigours of travel—the jolting of the carriage, for example—could bring on new symptoms or complications impossible to treat on such a journey.[82] Andrea left for Bergamo on 7 (or 8) September 1846, taking with him a partial score of Le duc d'Albe, the completed score of Rita, and a variety of personal effects, including jewelry.[83]

Attempts to move Donizetti back to Paris

In late December, early January 1847, visits from a friend from Vienna who lived in Paris—Baron Eduard von Lannoy—resulted in a letter from Lannoy to Giuseppe Donizetti in Constantinople outlining what he saw as a better solution: rather than have friends travel the five hours to see his brother, Lannoy recommended that Gaetano be moved to Paris where he could be taken care of by the same doctors. Giuseppe agreed and sent Andrea back to Paris, which he reached on 23 April. Visiting his uncle the following day, he found himself recognized. He was able to go on to convince the Paris Prefect, by threats of family action and general public concern, that the composer should be moved to an apartment in Paris. This took place on 23 June and, while there, he was able to take rides in his carriage and appeared to be much more aware of his surroundings. However, he was held under virtual house arrest by the police for several more months, although able to be visited by friends and even by Verdi while he was in Paris. Finally—on 16 August—in Constantinople, Giuseppe filed a formal complaint with the Austrian ambassador (given that the composer was an Austrian citizen).

In Paris, the police insisted on a further medical examination. Six doctors were called in and, of the six, only four approved of the travel. Then the police sent in their own doctor (who opposed the move), posted gendarmes outside the apartment, and forbade the daily carriage rides. Now desperate, Andrea then consulted three lawyers and sent detailed reports to his father in Constantinople. Finally, action taken by Count Sturmer of the Austrian Embassy in Turkey caused action to be taken from Vienna which, via the Embassy in Paris, sent a formal complaint to the French government. Within a few days, Donizetti was given permission to leave and he set out from Paris on what was to be a seventeen-day trip to Bergamo.[84]

Final journey to Bergamo

Arrangements had been made well ahead of time as to where Donizetti would live when he arrived in Bergamo. In fact, on his second visit to Paris, when it appeared that his uncle would return to Italy, Andrea had an agreement from the noble Scotti family for his uncle to be able to stay in their palace. The accompanying party of four consisted of Andrea, the composer's younger brother Francesco who had come specially from Bergamo for this purpose, Dr. Rendu, and nurse-custodian Antoine Pourcelot. They traveled by train to Amiens, then on to Brussels, after which they traveled in two coaches (one of which was Donizetti's, sent ahead to await the party). They crossed Belgium and Germany to Switzerland, crossing the Alps via the St Gotthard Pass, and came down into Italy arriving in Bergamo on the evening of 6 October, where they were welcomed by friends as well as the mayor.

Based on the report of the accompanying doctor, Donizetti did not appear to have suffered from the journey. He was settled comfortably in a large chair, speaking very rarely or only in occasional monosyllables, and mostly remaining detached from everyone around him. However, when Giovannina Basoni (who eventually became Baroness Scotti) played and sang arias from the composer's operas, he did appear to pay some attention. On the other hand, when the tenor Rubini visited and, together with Giovannina, sang music from Lucia di Lammermoor, Antonio Vasselli reported that there was no sign of recognition at all.[84] This condition continued well into 1848, more or less unchanged until a serious bout of apoplexy occurred on 1 April followed by further decline and the inability to take in food. Finally, after the intense night of 7 April, Gaetano Donizetti died on the afternoon of 8 April.

Initially Donizetti was buried in the cemetery of Valtesse but in 1875 his body was transferred to Bergamo's Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore near the grave of his teacher Simon Mayr.

Personal life

It was during the months which Donizetti spent in Rome for the production of Zoraida that he met the Vasselli family, with Antonio initially becoming a good friend. Antonio's sister Virginia was at that point only 13.[37] However, Virginia was to become Donizetti's wife in 1828. She gave birth to three children, none of whom survived and, within a year of his parents' deaths—on 30 July 1837—she also died from what is believed to be cholera or measles, but Ashbrook speculates that it was connected to what he describes as a "severe syphilitic infection."[85]

By nine years, he was the younger brother of Giuseppe Donizetti, who had become, in 1828, Instructor General of the Imperial Ottoman Music at the court of Sultan Mahmud II (1808–1839). The youngest of the three brothers was Francesco whose life was spent entirely in Bergamo, except for a brief visit to Paris during his brother's decline. He survived him by only eight months.

Critical reception

After the death of Bellini, Donizetti was the most significant composer of Italian opera until Verdi.[86] His reputation fluctuated,[87] but since the 1940s and 1950s his work has been increasingly performed.[88] His best known operas today are Lucia di Lammermoor, La fille du régiment, L'elisir d'amore and Don Pasquale.

Donizetti's compositions

Donizetti, a prolific composer, is best known for his operatic works, but he also wrote music in a number of other forms, including some church music, a number of string quartets, and some orchestral pieces. Altogether, he composed about 75 operas, 16 symphonies, 19 string quartets, 193 songs, 45 duets, 3 oratorios, 28 cantatas, instrumental concertos, sonatas, and other chamber pieces.

| Operas (see List of operas by Gaetano Donizetti) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choral works | |||||||

| Ave Maria | Grande Offertorio | Il sospiro | Messa da Requiem | Messa di Gloria e Credo | Miserere (Psalm 50) | ||

| Orchestral works | |||||||

| Allegro for Strings in C major | Larghetto, tema e variazioni in E flat major | Sinfonia Concertante in D major (1817)[89] | Sinfonia in A major | Sinfonia in C major | Sinfonia in D major (1818)[90] | Sinfonia in D minor | |

| Concertos | |||||||

| Concertino for Clarinet in B flat major | Concertino for English Horn in G major (1816) | Concertino in C minor for flute and chamber orchestra (1819) | Concertino for Flute and Orchestra in C major | Concertino for Flute and Orchestra in D major | Concertino for Oboe in F major | Concertino for Violin and Cello in D minor | Concerto for Violin and Cello in D minor |

| Concerto for 2 Clarinets "Maria Padilla" | |||||||

| Chamber works | |||||||

| Andante sostenuto for Oboe and Harp in F minor | Introduction for Strings in D major | Larghetto and Allegro for Violin and Harp in G minor | Largo/Moderato for Cello and Piano in G minor | Nocturnes (4) for Winds and Strings | Sonata for Flute and Harp | Sonata for Flute and Piano in C major | |

| Sinfonia for Winds in G minor (1817) | Quintet for Guitar and Strings no 2 in C major | Study for Clarinet no 1 in B flat major | Trio for Flute, Bassoon and Piano in F major | ||||

| Quartets for strings | |||||||

| String Quartet in D major | No. 3 in C minor: 2nd movement, Adagio ma non troppo | No. 4 in D major | No. 5 in E minor | No. 5 in E minor: Larghetto | No. 6 in G minor | No. 7 in F minor | No. 8 in B flat major |

| No. 9 in D minor | No. 11 in C major | No. 12 in C major | No. 13 in A major | No. 14 in D major | No. 15 in F major | No. 16 in B minor | No 17 in D major |

| No. 18 in E minor | No. 18 in E minor: Allegro | ||||||

| Piano works | |||||||

| Adagio and Allegro in G major | Allegro in C major | Allegro in F minor | Fugue in G minor | Grand Waltz in A major | Larghetto in A minor "Una furtiva lagrima" | Larghetto in C major | Pastorale in E major |

| Presto in F minor | Sinfonia in A major | Sinfonia No. 1 in C major | Sinfonia No. 1 in D major | Sinfonia No. 2 in C major | Sinfonia No. 2 in D major | Sonata in C major | Sonata in F major |

| Sonata in G major | Variations in E major | Variations in G major | Waltz in A major | Waltz in C major | Waltz in C major "The Invitation" | ||

References

Notes

- "Donizetti". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Donizetti, Gaetano". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Donizetti". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Smart, Mary Ann; Budden, Julian. "Donizetti, Gaetano". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Allitt 1991, p. 9

- Osborne 1994, p. 139

- Weinstock 1963, p. 13

- Black 1982, p. 1

- Black 1982, pp. 50–51

- Black 1982, p. 52

- Ashbrook & Hibberd 2001, p. 225

- Peschel & Peschel 1992.

- Weinstock 1963, pp. 5–6

- Mayr to the school administrators, in Weinstock, p. 6

- Ashbrook 1982, pp. 8–9

- Lines from Mayr's libretto, as spoken by Donizetti in 1811, quoted in Weinstock 1963, p. 8.

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 9

- Ashbrook 1982, pp. 9 ff.

- Allitt 1991, pp. 9–11

- Weinstock 1963, p. 19

- quoted in Ashbrook 1982, p. 16

- Weinstock 1963, p. 22

- Ashbrook 1982, pp. 18–19

- Ashbrook 1982, pp. 20–21

- Weinstock 1963, pp. 24–25

- In Osborne 1994

- Weinstock 1963, pp. 28–32

- in Weinstock, pp. 28–29

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 25

- Florimo's account, in Weinstock 1963, pp. 32–33

- in Weinstock 1963, p. 34

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 27

- in Weinstock, 1963, p. 37: Weinstock further asks the question as to why Donizetti spread "his energy and talent so thinly over so many compositions and continued to set librettos by Tottola and Giovanni Schmidt while conscious of their abysmal quality." Essentially, his answer is that the composer needed the money for his various commitments to his family, which included a younger brother and his parents.

- Ashbrok, 1982, p. 29

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 31

- Osborne 1994, p. 156

- Allitt 1991, pp. 27–28

- The Giornali in Ashbrook 1982, p. 32

- Weinstock 1963, pp. 43–44

- Allitt 1991, pp. 28–29

- Ashbrook 1982, pp. 38–39

- Allitt 1991, pp. 29–30

- Review in the Gazzetta privilegiata, in Weinstock 1963, p. 64

- Weinstock 1963, Performance history, pp. 325–328. Confirmed in Osborne 1994, pp. 194–197

- The plot of Scott's original novel is based on an actual incident that took place in 1669 in the Lammermuir Hills area of Lowland Scotland. The real family involved were the Dalrymples and the libretto retains much of Scott's basic intrigue, as well as very substantial changes in terms of characters and events.

- Mackerras, p. 29

- Parker and Ashbrook, p. 17

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 137

- Girardi, p. 1

- Allitt 1991, p. 40

- Allitt 1991, p. 41

- Weinstock 1963, p. 177: Donizetti to Vasselli, 25 July 1841, in Weinstock

- Rossini in Allitt 1991, p. 42

- Weinstock 1963, p. 184: A letter from a Doctor Galli which describes his condition

- Weinstock 1963, p. 186

- Donizetti to Antonio Dolci (a Bergamo friend), 15 September 1842, in Weinstock 1963, p. 186

- Weinstock 1963, pp. 188 ff.

- Weinstock 1963, p. 195

- Délécluze quoted in Weinstock 1963, p. 194.

- Allitt 1991, p. 43

- Ashbrook 1982, pp. 177–178

- Donizetti to Vasselli, 30 January 1843, in Weinstock 1963, p. 196

- Ashbrook 1982, pp. 178–179

- Donizetti to Mayr, 2 September 1843, in Weinstock 1963, p. 204

- Weinstock 1963, pp. 206–207

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 190

- Weinstock 1963, p. 217

- Weinstock 1963, p. 213

- Zavadini 1948

- Weinstock 1963, p. 215

- Verdi to Donizetti, in Weinstock 1963, p. 220

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 191. Further details of specific dates from Weinstock, pp. 221–224

- Weinstock, p. 227

- Weinstock 1963, pp. 228–229

- Weinstock 1963, Ch. X: August 1845 – September 1846, pp. 233–255

- Drs. Calmeil, Mitivié, and Ricord to Andrea Donizetti, 28 January 1846, in Weinstock 1963, p. 246

- Drs. Calmeil and Ricord to Andrea Donizetti, 31 January 1846, in Weinstock 1963, p. 247

- Weatherson 2013, pp. 12–17

- Weatherson 2013, pp. 12–14

- Report of 12 June 1846, in Weinstock 1963, p. 246

- Report of three doctors, 10 July 1846, in Weinstock 1963, p. 243

- Report from Drs. Calmeil, Ricord, and Moreau to Andrea Donizetti, 30 August 1846, in Weinstock 1963, pp. 254–255

- Weinstock and Ashbrook provide different departure days.

- Weinstock 1963, Ch. XI: September 1846 – April 1848, pp. 256–271

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 121

- "Gaetano Donizetti ", English National Opera

- http://www.donizettisociety.com/donizettiworks.htm

- http://www.interlude.hk/front/center-musical-universe-gaetano-donizetti/

- Weinstock 1963, p. 17

- Weinstock 1963, p. 20

Sources

- Allitt, John Stewart (1991), Donizetti – in the light of romanticism and the teaching of Johann Simon Mayr, Shaftesbury, Dorset, UK: Element Books. Also see Allitt's website

- Allitt, John Stewart (2003), Gaetano Donizetti – Pensiero, musica, opere scelte, Milano: Edizione Villadiseriane

- Ashbrook, Wiliam and Budden, Julian (1980),

"[Article title unknown]", The New Grove Masters of Italian Opera, London: Papermac. pp. 93–154

- Ashbrook, William (1982), Donizetti and his Operas, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27663-4, 0-521-23526-X

- Ashbrook, William (with John Black); Julian Budden (1998), "Gaetano Donizetti" in Stanley Sadie (Ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Volume 1. London: Macmillan Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-333-73432-2, 1-56159-228-5

- Ashbrook, Wiliam; Budden, Julian (2001), "[Article title unknown]" in Sadie, Stanley (Ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Volume 7, London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd. pp. 761–796.

- Ashbrook, William; Sarah Hibberd (2001), in Holden, Amanda (Ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 978-0-14-029312-8.

- Bini, Annalisa and Jeremy Commons (1997), Le prime rappresentazioni delle opere di Donizetti nella stampa coeva, Milan: Skira.

- Black, John (1982), Donizetti's Operas in Naples 1822–1848, London: The Donizetti Society

- Cassaro, James P. (2000), Gaetano Donizetti – A Guide to Research, New York: Garland Publishing.

- Donati-Petténi, Giuliano (1928), L'Istituto Musicale Gaetano Donizetti. La Cappella Musicale di Santa Maria Maggiore. Il Museo Donizettiano, Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d'Arti Grafiche. (In Italian)

- Donati-Petténi, Giuliano (1930), Donizetti, Milano: Fratelli Treves Editori. (In Italian)

- Donati-Petténi, Giuliano (1930), L'arte della musica in Bergamo, Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d'Arti Grafiche. (In Italian)

- Engel, Louis (1886), From Mozart to Mario: Reminiscences of Half a Century vols. 1 & 2., London, Richard Bentley.

- Giradi, Michele, "Donizetti e il grand-opéra: il caso di Les Martyrs" on www-5.unipv.it (in Italian)

- Gossett, Philip (1985), "Anna Bolena" and the Artistic Maturity of Gaetano Donizetti, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-313205-4

- Kantner, Leopold M (Ed.), Donizetti in Wien, papers from a symposium in various languages. Primo Ottocento, available from Edition Praesens. ISBN 978-3-7069-0006-5

- Keller, Marcello Sorce (1978), "Gaetano Donizetti: un bergamasco compositore di canzoni napoletane", Studi Donizettiani, Vol. III, pp. 100–107.

- Keller, Marcello Sorce (1984), "Io te voglio bene assaje: a Famous Neapolitan Song Traditionally Attributed to Gaetano Donizetti", The Music Review, Vol. XLV, No. 3–4, pp. 251–264. Also published as: Io te voglio bene assaje: una famosa canzone napoletana tradizionalmente attribuita a Gaetano Donizetti, La Nuova Rivista Musicale Italiana, 1985, No. 4, pp. 642–653.

- Mackerras, Sir Charles (1998). Lucia di Lammermoor (CD booklet). Sony Classical. pp. 29–33. ISBN 978-0-521-27663-4.

- Minden, Pieter (Ed.); Gaetano Donizetti (1999), Scarsa Mercè Saranno. Duett für Alt und Tenor mit Klavierbegleitung [Partitur]. Mit dem Faksimile des Autographs von 1815. Tübingen : Noûs-Verlag. 18 pp., [13] fol.; ISBN 978-3-924249-25-0. [Caesar vs. Cleopatra.]

- Osborne, Charles, (1994), The Bel Canto Operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini, Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-0-931340-71-0

- Parker, Roger; William Ashbrook (1994), "Poliuto: the Critical Edition of an 'International Opera'", in booklet accompanying the 1994 recording on Ricordi.

- Peschel, E[nid Rhodes]; Peschel, R[ichard E.] (May–June 1992). "Donizetti and the music of mental derangement: Anna Bolena, Lucia di Lammermoor, and the composer's neurobiological illness". Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 65 (3): 189–200. PMC 2589608. PMID 1285447.

- Saracino, Egidio (Ed.) (1993), Tutti I libretti di Donizetti, Garzanti Editore.

- Weatherson, Alexander (February 2013), "Donizetti at Ivry: Notes from a Tragic Coda", Newsletter No. 118, London: Donizetti Society.

- Weinstock, Herbert (1963), Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris and Vienna in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, New York: Random House.

- Zavadini, Guido (1948), Donizetti: Vita – Musiche – Epistolario, Bergamo.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gaetano Donizetti. |

- Donizetti Society (London) for further research. Online at donizettisociety.com

- Dotto, Gabriele; Roger Parker, (General Editors), "The Critical Edition of the Operas of Gaetano Donizetti published by Casa Ricordi, Milan, with the collaboration and contribution of Fondazione Donizetti, Bergamo" online at ricordi.com.

- List of Donizetti operas compiled by Stanford University on opera.stanford.edu

- "About the Composer: Gaetano Maria Donizetti" on the Manitoba Opera's website

- Donizetti biography on Arizona Opera website

- Libretti: source for a large number of Donizetti's operas

- Free scores by Gaetano Donizetti at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Gaetano Donizetti in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Gaetano Donizetti cylinder recordings, from the UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Library.