Ganj Dareh

Ganj Dareh (Persian: تپه گنج دره; "Treasure Valley" in Persian,[2] or "Treasure Valley Hill" if tepe/tappeh (hill) is appended to the name) is a Neolithic settlement in the Iranian Kurdistan. It is located in the Harsin County in east of Kermanshah Province, in the central Zagros Mountains.[2]

تپه گنج دره | |

The early village site of Ganj Darreh near Kermanshah | |

Location in the Near East  Ganj Dareh (Iran) | |

| Location | Kermanshah Province, Iran |

|---|---|

| Region | Gamas-Ab Valley |

| Coordinates | 34.2721°N 47.4758°E |

| Altitude | 1,400 m (4,593 ft)[1] |

| Type | mound settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | ca. 10,000 BP |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Associated with | pastoralists |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1967-1974[1] |

Research history

First discovered in 1965, it was excavated by Canadian archaeologist, Philip Smith during the 1960s and 1970s, for four field seasons.[2][3]

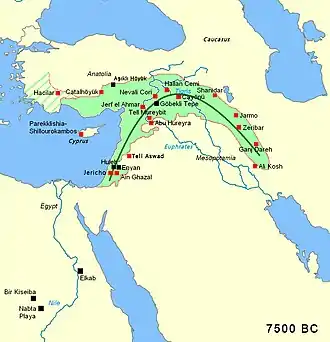

The oldest settlement remains on the site date back to ca. 10,000 years ago,[4] and have yielded the earliest evidence for goat domestication in the world.[5][6][7] The only evidence for domesticated crops found at the site so far is the presence of two-row barley.[1]

The remains have been classified into five occupation levels, from A, at the top, to E.[8]

Ceramics

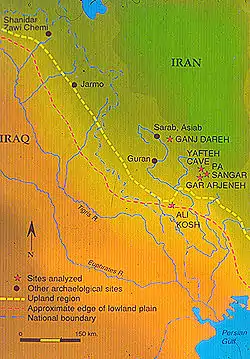

Ganj Dareh is important in the study of Neolithic ceramics in Luristan and Kurdistan. This is a period beginning in the late 8th millennium, and continuing to the middle of the 6th millennium BC. Also, the evidence from two other excavated sites nearby is important, from Tepe Guran, and Tepe Sarab (shown on the map in this article). They are all located southwest of Harsin, on the Mahidasht plain, and in the Hulailan valley.[9]

At Ganj Dareh, two early ceramic traditions are evident. One is based on the use of clay for figurines and small geometric pieces like cones and disks. These are dated ca. 7300-6900 BC.

The other ceramic tradition originated in the use of clay for mud-walled buildings (ca. 7300 BC). These traditions are also shared by Tepe Guran, and Tepe Sarab.[9] Tepe Asiab is also located near Tepe Sarab, and may be the earliest of all these sites. Both sites appear to have been seasonally occupied. Ali Kosh is also a related site of the Neolithic period.

Genetics

Researchers sequenced the genome from the petrous bone of a 30-50 year old woman from Ganj Dareh, GD13a. mtDNA analysis shows that she belonged to Haplogroup X. She is phenotypically similar to the Anatolian early farmers and Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers. Her DNA revealed that she had black hair, brown eyes and was lactose intolerant. The derived SLC45A2 variant associated with light skin was not observed in GD13a, but the derived SLC24A5 variant which is also associated with the same trait was observed.[1]

GD13a is genetically closest to the ancient Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers identified from human remains from Georgia (Satsurblia Cave and Kotias Klde), while also sharing genetic affinities with the people of the Yamna culture and the Afanasevo culture. She belonged to a population that was genetically distinct from the Neolithic Anatolian farmers. In terms of modern populations, she shows some genetic affinity with the Baloch people, Makrani caste and Brahui people due to Ancient Caucasus Hunter-Gatherer ancestry found in some Indians, in actuality they are the closest to modern Zoroastrians in Iran. Her population did not contribute very much genetically to modern Europeans.[1]

The oldest sample of haplogroup R2a was observed in the remains of a Neolithic human from Ganj Dareh in western Iran.[10][11]

Gallery

Ganj Dareh site

Ganj Dareh site_Tappeh_Sarab%252C_Kermanshah_ca._7000-6100_BCE_Neolithic_period%252C_National_Museum_of_Iran.jpg.webp) Clay human figurine (Fertility goddess) Tepe Sarab, near Ganj Dareh, Kermanshah ca. 7000-6100 BCE, Neolithic period, National Museum of Iran

Clay human figurine (Fertility goddess) Tepe Sarab, near Ganj Dareh, Kermanshah ca. 7000-6100 BCE, Neolithic period, National Museum of Iran Ganj Dareh objects

Ganj Dareh objects A clay boar figurine from the Neolithic period, found at Tepe Sarab, kept at the Museum of Ancient Iran.

A clay boar figurine from the Neolithic period, found at Tepe Sarab, kept at the Museum of Ancient Iran.

References

- Gallego-Llorente, M.; et al. (2016). "The genetics of an early Neolithic pastoralist from the Zagros, Iran". Scientific Reports. 6: 31326. doi:10.1038/srep31326. PMC 4977546. PMID 27502179.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. - Smith, Philip E.L. Architectural Innovation and Experimentation at Ganj Dareh, Iran, World Archaeology, Vol. 21, No. 3 (February, 1990), pp. 323-335

- Smith, Philip E.L., Ganj Dareh Tepe, Paleorient, Vol. 2, Issue 2-1, pp.207-09 (1974)

- Zeder, Melinda A.; Hesse, Brian (2000). "The Initial Domestication of Goats (Capra hircus) in the Zagros Mountains 10,000 Years Ago" (PDF). Science. 287 (5461): 2254–7. doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2254. PMID 10731145. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

- What's Bred in the Bone, Discover (magazine), July 2000 ("After investigating bone collections from ancient sites across the Middle East, she found a dearth of adult male goat bones—and an abundance of female and young male remains—from a 10,000-year-old settlement called Ganj Dareh, in Iran's Zagros Mountains. This provides the earliest evidence of domesticated livestock, Zeder says.")

- Harris, David R. (ed.) The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia, pp. 208, 249-52 (UCL Press 1996) (Reprint ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3)

- Natural History Highlight: Old Goats In Transition, National Museum of Natural History (July 2000)

- Yelon, A., et al. Thermal Analysis of Early Neolithic Pottery From Tepe Ganj Dareh, Iran, in Materials issues in art and archaeology III (1992)

- Peder Mortensen (2011), CERAMICS: The Neolithic Period in Central and Western Persia. iranicaonline.org

- Lazaridis et al. (2016)

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick J.; Moorjani, Priya; Lazaridis, Iosif; Mark, Lipson; Mallick, Swapan; Rohland, Nadin; Bernardos, Rebecca; Kim, Alexander M. (2018-03-31). "The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia". bioRxiv: 292581. doi:10.1101/292581.

Bibliography

- Agelarakis A., The Palaeopathological Evidence, Indicators of Stress of the Shanidar Proto-Neolithic and the Ganj-Dareh Tepe Early Neolithic Human Skeletal Collections. Columbia University, 1989, Doctoral Dissertation, UMI, Bell & Howell Information Company, Michigan 48106.

- Robert J. Wenke: "Patterns in Prehistory: Humankind's first three million years" (1990)

External links

- Peder Mortensen (2011), CERAMICS: The Neolithic Period in Central and Western Persia. iranicaonline.org

- Natural History Highlight: Old Goats In Transition, National Museum of Natural History (July 2000)

Relative chronology

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.