Gastarbeiter

Gastarbeiter (pronounced [ˈɡastˌʔaɐ̯baɪtɐ] (![]() listen); both singular and plural; literally German for 'guest worker') are foreign or migrant workers, particularly those who had moved to West Germany between 1955 and 1973, seeking work as part of a formal guest worker program (Gastarbeiterprogramm). Other countries had similar programs: in the Netherlands and Belgium it was called the gastarbeider program; in Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland it was called arbetskraftsinvandring (workforce-immigration); and in East Germany such workers were called Vertragsarbeiter. The term was used during the Nazi era as was Fremdarbeiter (German for 'foreign worker'). However, the latter term had negative connotations, and was no longer used after World War II.

listen); both singular and plural; literally German for 'guest worker') are foreign or migrant workers, particularly those who had moved to West Germany between 1955 and 1973, seeking work as part of a formal guest worker program (Gastarbeiterprogramm). Other countries had similar programs: in the Netherlands and Belgium it was called the gastarbeider program; in Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland it was called arbetskraftsinvandring (workforce-immigration); and in East Germany such workers were called Vertragsarbeiter. The term was used during the Nazi era as was Fremdarbeiter (German for 'foreign worker'). However, the latter term had negative connotations, and was no longer used after World War II.

The term is widely used in Russia (Russian: гастарбайтер) to refer to foreign workers from post-USSR or third-world countries.[1][2]

Historical background

Following World War II there were severe labour shortages in continental northern Europe, and high unemployment in southern European countries and in Turkey.[3]

West Germany

During the 1950s and 1960s, West Germany signed bilateral recruitment agreements with a number of countries:[4] Italy (22 November 1955), Spain (29 March 1960), Greece (30 March 1960), Turkey (30 October 1961), Morocco (21 June 1963), South Korea (16 December 1963), Portugal (17 March 1964), Tunisia (18 October 1965), and Yugoslavia (12 October 1968).[5][6] These agreements allowed the recruitment of guest workers to work in the industrial sector in jobs that required few qualifications.

There were several justifications for these arrangements. Firstly, during the 1950s, Germany experienced a so-called Wirtschaftswunder or "economic miracle" and needed laborers.[7] The labour shortage was made more acute after the building of the Berlin Wall in August 1961, which drastically reduced the large-scale flow of East German workers. Secondly, West Germany justified these programs as a form of developmental aid. It was expected that guest workers would learn useful skills which could help them build their own countries after returning home.[3]

The first guest workers were recruited from European nations. However, Turkey pressured West Germany to admit its citizens as guest workers.[3] Theodor Blank, Secretary of State for Employment, opposed such agreements. He held the opinion that the cultural gap between Germany and Turkey would be too large and also held the opinion that Germany didn't need any more laborers because there were enough unemployed people living in the poorer regions of Germany who could fill these vacancies. The United States, however, put some political pressure on Germany, wanting to stabilize and create goodwill from a potential ally. West Germany and Turkey reached an agreement in 1961.[8]

After 1961 Turkish citizens (largely from rural areas) soon became the largest group of guest workers in West Germany. The expectation at the time on the part of both the West German and Turkish governments was that working in Germany would be only "temporary." The migrants, mostly male, were allowed to work in Germany for a period of one or two years before returning to their home country in order to make room for other migrants. Some migrants did return, after having built up savings for their return.

Until very recently, Germany had not been perceived as a country of immigration ("kein Einwanderungsland") by both the majority of its political leaders and the majority of its population. When the country's political leaders realized that many of the persons from certain countries living in Germany were jobless, some calculations were done and according to those calculations, paying unemployed foreigners for leaving the country was cheaper in the long run than paying unemployment benefits. A "Gesetz zur Förderung der Rückkehrbereitsschaft" ("law to advance the willingness to return home") was passed. The government started paying jobless people from a number of countries, such as Turks, Moroccans and Tunisians, a so-called Rückkehrprämie ("repatriation grant") or Rückkehrhilfe ("repatriation help") if they returned home. A person returning home received 10,500 Deutsche Mark and an additional 1,500 Deutsche Mark for his spouse and also 1,500 Deutsche Mark for each of his children if they returned to the country of his origin.[9][10]

The agreement with Turkey ended in 1973 but few workers returned because there were few good jobs in Turkey.[11] Instead they brought in wives and family members and settled in ethnic enclaves.[12]

In 2013 it was revealed that ex-chancellor Helmut Kohl had plans to halve the Turkish population of Germany in the 1980s.[13]

By 2010 there were about 4 million people of Turkish descent in Germany. The generation born in Germany attended German schools, but some had a poor command of either German or Turkish, and thus had either low-skilled jobs or were unemployed. Most are Muslims and are presently reluctant to become German citizens.[14][15]

Germany used the jus sanguinis principle in its nationality or citizenship law, which determined the right to citizenship based on a person's German ancestry, and not by place of birth. Accordingly, children born in Germany of a guest worker were not automatically entitled to citizenship, but were granted the "Aufenthaltsberechtigung" ("right to reside") and might choose to apply for German citizenship later in their lives, which was granted to persons who had lived in Germany for at least 15 years and fulfilled a number of other preconditions (they must work for their living, they should not have a criminal record, and other preconditions). Today, children of foreigners born on German soil are granted German citizenship automatically if the parent has been in Germany for at least eight years as a legal immigrant. As a rule those children may also have the citizenship of the parents' home country. Those between 18 and 23 years of age must choose to keep either German citizenship or their ancestral citizenship. The governments of the German States have begun campaigns to persuade immigrants to acquire German citizenship.[16]

Those who hold German citizenship have a number of advantages. For example, only those holding German citizenship may vote in certain elections. Also, some jobs may only be performed by German citizens. As a rule these are jobs which require a deep identification with the government. Only those holding German citizenship are allowed to become a schoolteacher, a police officer, or a soldier. Most jobs, however, do not require German citizenship. Those who do not hold German citizenship but instead just a "right to reside" may still receive many social benefits. They may attend schools, receive medical insurance, be paid children's benefits, receive welfare and housing assistance.

In many cases guest workers integrated neatly into German society, in particular those from other European countries with a Christian background, even if they started out poor. For example, Dietrich Tränhardt researched this topic in relation to Spanish guest workers. While many Spanish that came to Germany were illiterate peasants, their offspring were academically successful (see: Academic achievement among different groups in Germany) and do well in the job market. Spanish Gastarbeiter were more likely to marry Germans, which could be considered an indicator of assimilation. According to a study in 2000, 81.2% of all Spanish or partly Spanish children in Germany were from a Spanish-German family.[17]

There were some, and still are, tensions in German society, because Muslim immigrants feel they have been religiously discriminated against. For example, while the Christian churches are allowed to collect church tax in Germany, Muslim mosques are not able to do so as they are not as yet organised in a cooperative association (which is sometimes criticised as forcing Christian organisation-style on non-Christians). While German universities have educated Jewish, Catholic and Protestant clerics and religious teachers, in the past none of the German universities have offered education for Muslim teachers and clerics. However, today such university courses exist.[18]

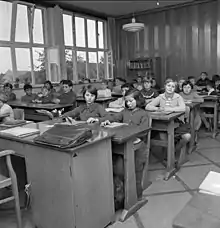

Muslims were often also not pleased to find the Christian cross displayed in German classrooms, something that at the time was relatively common. The fact that most schools offer Catholic and Protestant religious education and ethics but no Islamic religious education has also been criticised (especially because religious education is compulsory, replaceable by ethics). Students are allowed to wear a normal headscarf in school, however in 2010 a Muslim student sued a Gymnasium headmaster, because she was not allowed to wear a Khimar in school.[19]

East Germany

After the division of Germany into East and West in 1949, East Germany faced an acute labour shortage, mainly because of East Germans fleeing into the western zones occupied by the Allies; in 1963 the GDR (German Democratic Republic) signed its first guest worker contract with Poland. In contrast to the guest workers in West Germany, the guest workers that arrived in East Germany came mainly from Communist countries allied with the Soviets and the SED used its guest worker programme to build international solidarity among fellow communist governments.

The guest workers in East Germany came mainly from the Eastern Bloc, Vietnam, North Korea, Angola, Mozambique, and Cuba. Residency was typically limited to only three years. The conditions East German Gastarbeiter had to live in were much harsher than the living conditions of the Gastarbeiter in West Germany; accommodation was mainly in single-sex dormitories.[20] In addition, contact between guest workers and East German citizens was extremely limited; Gastarbeiter were usually restricted to their dormitory or an area of the city which Germans were not allowed to enter - furthermore sexual relations with a German led to deportation.[20][21][22] Female Vertragsarbeiter were not allowed to become pregnant during their stay. If they did, they were forced to have an abortion.[23]

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification in 1990, the population of guest workers still remaining in the former East Germany faced deportation, premature discontinuation of residence and work permits as well as open discrimination in the workplace. Of the 100,000 guest workers remaining in East Germany after reunification, about 75% left because of the rising tide of xenophobia in former East German territories. Vietnamese were not considered legal immigrants and lived in "grey area". Many started selling goods at the roadside. Ten years after the fall of the Berlin wall most Vietnamese were granted the right to reside however and many started opening little shops.[21]

After the reunification, Germany offered the guest workers US$2,000 and a ticket home if they left. The country of Vietnam did not accept the ones back who refused to accept the money, Germany considered them "illegal immigrants" after 1994. In 1995, Germany paid $140 million to the Vietnamese government and made a contract about repatriation which stated that repatriation could be forced if necessary. By 2004, 11,000 former Vietnamese guest workers had been repatriated, 8,000 of them against their will.[24]

The children of the Vietnamese Gastarbeiter caused what has been called the "Vietnamese miracle".[25] As shown by a study while in the Berlin districts of Lichtenberg and Marzahn, where those of Vietnamese descent account for only 2% of the general population, but make up 17% of the university preparatory school population of those districts.[26] According to the headmaster of the Barnim Gymnasium, for a university preparatory school (Gymnasium) that has a focus on the natural sciences, 30% of the school's freshmen come from Vietnamese families.[25]

Austria

On December 28, 1961, under the Raab-Olah agreement, Austria began a recruitment agreement with Spain, but compared to West Germany and Switzerland, the wage level in Austria was not attractive to many potential Spanish job-seekers.[27] However, the agreements signed with Turkey (1963) and Yugoslavia (1966) were more successful, resulting in approximately 265,000 people migrating to Austria from these two countries between 1969 and 1973, until being halted by the early 1970s economic crisis. In 1973, 78.5% of guest workers in Austria came from Yugoslavia and 11.8% from Turkey.[28]

Currently

Today the term Gastarbeiter is no longer accurate, as the former guest worker communities, insofar as they have not returned to their countries of origins, have become permanent residents or citizens, and therefore are in no meaningful sense "guests". However, although many of the former "guest workers" have now become German citizens, the term Ausländer or "foreigner" is still colloquially applied to them as well as to their naturalised children and grandchildren. A new word has been used by politicians for several years: Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund (German term for: people with an immigration background). The term was thought to be politically correct because it includes both immigrants and those who, being naturalized, cannot be referred to as immigrants—who are colloquially (and not by necessity xenophobically) called "naturalized immigrants" or "immigrants with a German passport". It also applies to German-born descendants of people who immigrated after 1949. To emphasize their Germanness, they are also quite often called fellowcitizens, which may result in calling "our Turkish fellow citizens" also those who are foreigners still, or even such Turks in Turkey who never had any contact to Germany.

Gastarbeiter, as a historical term however, referring to the guest worker programme and situation of the 1960s, is neutral and remains the most correct designation. In literary theory, some German migrant writers (e.g. Rafik Schami) use the terminology of "guest" and "host" provocatively.

The term Gastarbeiter lives on in Serbian, Bosnian, Croatian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Slovene languages, generally meaning "expatriate" (mostly referring to a second generation from the former Yugoslavia or Bulgaria born or living abroad). The South Slavic spelling reflects the local pronunciation of gastarbajter (in Cyrillic: гастарбаjтер or гастарбайтер). In Belgrade's jargon, it is commonly shortened to gastoz (гастоз) derived by the Serbian immigrant YouTube star nicknamed "Gasttozz", and in Zagreb's to gastić. Sometimes, in a negative context, they would be referred as Švabe and gastozi as well, after the Danube Swabians that inhabited the former Yugoslavia. This is often equated to the English term "rich kid/spoiled brat" due to the unprecedented wealth that gastarbeiters accumulate compared to their relatives that still live in the former Yugoslavia that often struggle to get the equal amount due to high employment rates across that region.

In modern Russia, the transliterated term gastarbeiter (гастарбайтер) is used to denote workers from former Soviet republics coming to Russia (mainly Moscow and Saint Petersburg) in search of work. These workers come primarily from Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, and Tajikistan; also for a guest worker from outside Europe, from China, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Angola, Mozambique, and Ethiopia. In contrast to such words as gastrolle (гастроль, сoncert tour), "gast professor" (invited to read the course at another university), which came to Russian from German, the word gastarbeiter is not neutral in modern Russian and has a negative connotation.

Notable Gastarbeiter

Sons of Gastarbeiter:

See also

Notes

- Felperin, Leslie (1 July 2010). "Gastarbeiter". Variety. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Beyond the gastarbeiter: the other side of post-Soviet migration". openDemocracy. 18 September 2012.

- Gerling, Vera: Soziale Dienste für zugewanderte Senioren/innen: Erfahrungen aus Deutschland, ISBN 978-3-8311-2803-7, S.78

- Horrocks, David; Kolinsky, Eva (11 September 1996). "Turkish Culture in German Society Today". Berghahn Books – via Google Books.

- Germany: Immigration in Transition by Veysel Oezcan. Social Science Centre Berlin. July 2004.

- Kaja Shonick, "Politics, Culture, and Economics: Reassessing the West German Guest Worker Agreement with Yugoslavia," Journal of Contemporary History, Oct 2009, Vol. 44 Issue 4, pp 719-736

- "Materieller und geistiger Wiederaufbau Österreichs - ORF ON Science". sciencev1.orf.at.

- Heike Knortz: Diplomatische Tauschgeschäfte. "Gastarbeiter" in der westdeutschen Diplomatie und Beschäftigungspolitik 1953-1973. Böhlau Verlag, Köln 2008

- S. Dünkel (2008) "Interkulturalität und Differenzwahrnehmung in der Migrationsliteratur", p. 20

- IAB: "Gesetz zur Förderung der Rückkehrbereitschaft von Ausländern"

- Stephen Castles, "The Guests Who Stayed - The Debate on 'Foreigners Policy' in the German Federal Republic," International Migration Review Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 517-534 in JSTOR

- Gottfried E. Volker, "Turkish Labour Migration to Germany: Impact on both Economies," Middle Eastern Studies, Jan 1976, Vol. 12 Issue 1, pp 45-72

- "Kohl Defends Plan to Halve Turkish Population". Spiegel Online. 2 August 2013.

- Katherine Pratt Ewing, "Living Islam in the Diaspora: Between Turkey and Germany," South Atlantic Quarterly, Volume 102, Number 2/3, Spring/Summer 2003, pp. 405-431 in Project MUSE

- Ruth Mandel, Cosmopolitan Anxieties: Turkish Challenges to Citizenship and Belonging in Germany (Duke University Press, 2008)

- zuletzt aktualisiert: 14.09.2009 - 15:02 (14 September 2009). "NRW-Regierung startet Einbürgerungskampagne: Mehr Ausländer sollen Deutsche werden | RP ONLINE". Rp-online.de. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- Thränhardt, Dietrich (4 December 2006). "Spanische Einwanderer schaffen Bildungskapital: Selbsthilfe-Netzwerke und Integrationserfolg in Europa Archived 30 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine" (in German). Universität Münster.

- Die Zeit, Hamburg, Germany (23 December 2009). "Religionsunterricht: Der Islam kommt an die Universitäten | Studium | ZEIT ONLINE" (in German). Zeit.de. Retrieved 13 October 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Die Zeit, Hamburg, Germany (5 February 2010). "Schülerinnen im Schleier: Umstrittener Dress-Code in der Schule | Gesellschaft | ZEIT ONLINE" (in German). Zeit.de. Retrieved 13 October 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stepahn Lanz: "Berlin aufgemischt - abendländisch - multikulturell - kosmopolitisch? Die politische Konstruktion einer Einwanderungsstadt". 2007. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag; p. 113

- taz, die tageszeitung (25 January 2010). "Vietnamesen in Deutschland: Unauffällig an die Spitze". taz.de. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- Pfohl, Manuela (1 October 2008), "Vietnamesen in Deutschland: Phuongs Traum", Stern, retrieved 18 October 2008

- Karin Weiss: "Die Einbindung ehemaliger vietnamesischer Vertragsarbeiterinnen und Vertragsarbeiter in Strukturen der Selbstorganisation", In: Almut Zwengel: "Die Gastarbeiter der DDR - politischer Kontext und Lebenswelt". Studien zur DDR Gesellschaft; p. 264

- Minority rights group international. World directory of Minorities and Indigenous people --> Europe --> Germany --> Vietnamese

- Die Zeit, Hamburg, Germany. "Integration: Das vietnamesische Wunder | Gesellschaft | ZEIT ONLINE" (in German). Zeit.de. Retrieved 13 October 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Von Berg, Stefan; Darnstädt, Thomas; Elger, Katrin; Hammerstein, Konstantin von; Hornig, Frank; Wensierski, Peter: "Politik der Vermeidung". Spiegel.

- "50 Jahre Gastarbeiter in Österreich". news.ORF.at (in German). 27 December 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- "Anwerbe-Abkommen mit Türkei – geschichtlicher Hintergrund | Medien Servicestelle Neue ÖsterreicherInnen". web.archive.org. 18 May 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/09/biontechs-covid-vaccine-a-shot-in-the-arm-for-germanys-turkish-community

References

- Behrends, Jan C., Thomas Lindenberger and Patrice Poutrus, eds. Fremd und Fremd-Sein in der DDR: Zu historischen Ursachen der Fremdfeindlichkeit in Ostdeutschland. Berlin: Metropole Verlag, 2003.

- Chin, Rita, The Guest Worker Question in Postwar Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- Chin, Rita, Heide Fehrenbach, Geoff Eley and Atina Grossmann. After the Nazi Racial State: Difference and Democracy in Germany and Europe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

- Göktürk, Deniz, David Gramling and Anton Kaes. Germany in Transit: Nation and Migration 1955-2005. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

- Horrocks, David, and Eva Kolinsky, eds. Turkish Culture in German Society Today (Berghahn Books, 1996) online

- Koop, Brett. German Multiculturalism: Immigrant Integration and the Transformation of Citizenship Book (Praeger, 2002) online

- Kurthen, Hermann, Werner Bergmann and Rainer Erb, eds. Antisemitism and Xenophobia in Germany after Unification. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- O'Brien, Peter. "Continuity and Change in Germany's Treatment of Non-Germans," International Migration Review Vol. 22, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 109–134 in JSTOR

- Yurdakul Gökce. From Guest Workers into Muslims: The Transformation of Turkish Immigrant Organisations in Germany (Cambridge Scholars Press; 2009)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gastarbeiter. |