Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

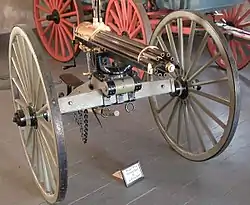

| Gatling gun | |

|---|---|

1876 Gatling gun kept at Fort Laramie National Historic Site | |

| Type | Rapid-fire gun, hand cranked Machine gun |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1862–1911 |

| Used by | United States Russian Empire British Empire France Empire of Japan Qing Empire Siam Empire Korean Empire Chile Peru |

| Wars | American Civil War Anglo-Zulu War Indian Wars Spanish–American War Philippine–American War Boxer Rebellion |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Richard Jordan Gatling |

| Designed | 1861 |

| Manufacturer | Eagle Iron Works Cooper Firearms Manufacturing Company Colt Manufacturing Company American Ordnance Company |

| Produced | 1862-1903 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 170 lb (77.2 kg)[1] |

| Length | 42.5 in (1,079 mm) |

| Barrel length | 26.5 in (673 mm) |

| Crew | Four-man crew |

| Cartridge | .30-40 Krag .45-70 Government .30-06 Springfield .43 Spanish 11x60 mm Mauser |

| Caliber | .308 inches (7.8 mm) |

| Barrels | 6–10 |

| Action | Crank handle |

| Rate of fire | 200 rounds per minute in .58 caliber, 400-900 rounds per minute in .30 caliber[2][3] |

The Gatling gun's operation centered on a cyclic multi-barrel design which facilitated cooling and synchronized the firing-reloading sequence. As the handwheel is cranked, the barrels rotate clockwise and each barrel sequentially loads a single round of cartridge from a top-mounted magazine, fires off the shot when it reaches a set position (usually at 4 o'clock), then ejects the spent casing out of the left side at the bottom, after which the barrel is empty and allowed to cool until rotated back to the top position and gravity-fed another new round. This configuration eliminated the need for a single reciprocating bolt design and allowed higher rates of fire to be achieved without the barrels overheating quickly.

One of the best-known early rapid-fire firearms, the Gatling gun saw occasional use by the Union forces during the American Civil War, which was the first time it was employed in combat. It was later used in numerous military conflicts, including the Boshin War, the Anglo-Zulu War and the assault on San Juan Hill during the Spanish–American War.[4] It was also used by the Pennsylvania militia in episodes of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, specifically in Pittsburgh. Gatling guns were even mounted aboard ships.[5]

Design

The Gatling gun operated by a hand-crank mechanism, with six barrels revolving around a central shaft (although some models had as many as ten). Each barrel fires once per revolution at about the same position. The barrels, a carrier, and a lock cylinder were separate and all mounted on a solid plate revolving around a central shaft, mounted on an oblong fixed frame. Turning the crank rotated the shaft. The carrier was grooved and the lock cylinder was drilled with holes corresponding to the barrels.

The casing was partitioned, and through this opening, the barrel shaft was journaled. In front of the casing was a cam with spiral surfaces. The cam imparted a reciprocating motion to the locks when the gun rotated. Also in the casing was a cocking ring with projections to cock and fire the gun. Each barrel had a single lock, working in the lock cylinder on a line with the barrel. The lock cylinder was encased and joined to the frame. Early models had a fibrous matting stuffed in among the barrels, which could be soaked with water to cool the barrels down. Later models eliminated the matting-filled barrels as being unnecessary.

Cartridges, held in a hopper, dropped individually into the grooves of the carrier. The lock was simultaneously forced by the cam to move forward and load the cartridge, and when the cam was at its highest point, the cocking ring freed the lock and fired the cartridge. After the cartridge was fired the continuing action of the cam drew back the lock bringing with it the spent casing which then dropped to the ground.

The grouped barrel concept had been explored by inventors since the 18th century, but poor engineering and the lack of a unitary cartridge made previous designs unsuccessful. The initial Gatling gun design used self-contained, reloadable steel cylinders with a chamber holding a ball and black-powder charge, and a percussion cap on one end. As the barrels rotated, these steel cylinders dropped into place, were fired, and were then ejected from the gun. The innovative features of the Gatling gun were its independent firing mechanism for each barrel and the simultaneous action of the locks, barrels, carrier, and breech.

The ammunition that Gatling eventually implemented was a paper cartridge charged with black powder and primed with a percussion cap because self-contained brass cartridges were not yet fully developed and available. The shells were gravity-fed into the breech through a hopper or simple box "magazine" with an unsprung gravity follower on top of the gun. Each barrel had its own firing mechanism.

Despite self-contained brass cartridges replacing the paper cartridge in the 1860s, it wasn't until the Model 1881 that Gatling switched to the 'Bruce'-style feed system (U.S. Patents 247,158 and 343,532) that accepted two rows of .45-70 cartridges. While one row was being fed into the gun, the other could be reloaded, thus allowing sustained fire. The final gun required four operators. By 1886, the gun was capable of firing more than 400 rounds per minute.

The smallest-caliber gun also had a Broadwell drum feed in place of the curved box of the other guns. The drum, named after L. W. Broadwell, an agent for Gatling's company, comprised twenty stacks of rounds arranged around a central axis, like the spokes of a wheel, each holding twenty cartridges with the bullet noses oriented toward the central axis. This invention was patented in U. S. 110,338. As each stack emptied, the drum was manually rotated to bring a new stack into use until all 400 rounds had been fired. A more common variant had 240 rounds in twenty stands of fifteen.

By 1893, the Gatling was adapted to take the new .30 Army smokeless cartridge. The new M1893 guns featured six barrels, later increased to ten barrels, and were capable of a maximum (initial) rate of fire of 800–900 rounds per minute, though 600 rpm was recommended for continuous fire.[3][6] Dr. Gatling later used examples of the M1893 powered by electric motor and belt to drive the crank.[7] Tests demonstrated the electric Gatling could fire bursts of up to 1,500 rpm.

The M1893, with minor revisions, became the M1895, and 94 guns were produced for the U.S. Army by Colt. Four M1895 Gatlings under Lt. John H. Parker saw considerable combat during the Santiago campaign in Cuba in 1898. The M1895 was designed to accept only the Bruce feeder. All previous models were unpainted, but the M1895 was painted olive drab (O.D.) green, with some parts left blued.

The Model 1900 was very similar to the model 1895, but with only a few components finished in O.D. green. The U.S. Army purchased several M1900s. All Gatling Models 1895–1903 could be mounted on an armored field carriage. In 1903, the Army converted its M1900 guns into .30 Army to fit the new .30-03 cartridge (standardized for the M1903 Springfield rifle) as the M1903. The later M1903-'06 was an M1903 converted to .30-06. This conversion was principally carried out at the Army's Springfield Armory arsenal repair shops. All models of Gatling guns were declared obsolete by the U.S. military in 1911, after 45 years of service.[8]

The original Gatling gun was a field weapon that used multiple rotating barrels turned by a hand crank, and firing loose (no links or belt) metal cartridge ammunition using a gravity feed system from a hopper. The Gatling gun's innovation lay in the use of multiple barrels to limit overheating, a rotating mechanism, and a gravity-feed reloading system, which allowed unskilled operators to achieve a relatively high rate of fire of 200 rounds per minute.[9]

Although the first Gatling gun was capable of firing continuously, it required a person to crank it; therefore it was not a true automatic weapon. The Maxim gun, invented and patented in 1883, was the first true fully automatic weapon, making use of the fired projectile's recoil force to reload the weapon. Nonetheless, the Gatling gun represented a huge leap in firearm technology.

Before the Gatling gun, the only weapons available to military forces capable of firing many projectiles in a short space of time were mass-firing volley weapons, like the Belgian and French mitrailleuse of the 1860s and 1870s, and field cannons firing canister shot, much like an upsized shotgun. The latter was widely used during and after the Napoleonic Wars. Although the maximum rate of fire was increased by firing multiple projectiles simultaneously, these weapons still needed to be reloaded after each discharge, which for multi-barrel systems like the mitrailleuse was cumbersome and time-consuming. This negated much of the advantage of their high rate of fire per discharge, making them much less powerful on the battlefield. In comparison, the Gatling gun offered a rapid and continuous rate of fire without having to be manually reloaded by opening the breech.

Early multi-barrel guns were approximately the size and weight of artillery pieces and were often perceived as a replacement for cannons firing grapeshot or canister shot.[10] Compared with earlier weapons such as the mitrailleuse, which required manual reloading, the Gatling gun was more reliable and easier to operate and had a lower, but continuous rate of fire. The large wheels required to move these guns around required a high firing position, which increased the vulnerability of their crews.[10]

Sustained firing of black powder cartridges generated a cloud of smoke, making concealment impossible until smokeless powder became available in the late 19th century.[11] When operators were firing Gatling guns against troops of industrialized nations, they were at risk, being vulnerable to artillery they could not reach and snipers they could not see.[10]

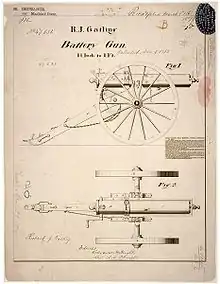

History

The Gatling gun was designed by the American inventor Dr. Richard J. Gatling in 1861 and patented on November 4, 1862.[12][9] Gatling wrote that he created it to reduce the size of armies and so reduce the number of deaths by combat and disease, and to show how futile war is.[13]

The US Army adopted Gatling guns in several calibers, including .42 caliber, .45-70, .50 caliber, 1 inch, and (M1893 and later) .30 Army, with conversions of M1900 weapons to .30-03 and .30-06.[14][15] The .45-70 weapon was also mounted on some US Navy ships of the 1880s and 1890s.[16]

British manufacturer James George Accles, previously employed by Colt 1867–1886, developed a modified Gatling gun circa 1888 known as the Accles Machine Gun.[17] Circa 1895 the American Ordnance Company acquired the rights to manufacture and distribute this weapon in the Americas. It was trialed by the US Navy in December 1895, and was said to be the only weapon to complete the trial out of five competing weapons, but was apparently not adopted by US forces.[18]

American Civil War and the Americas

The Gatling gun was first used in warfare during the American Civil War. Twelve of the guns were purchased personally by Union commanders and used in the trenches during the Siege of Petersburg, Virginia (June 1864—April 1865).[19] Eight other Gatling guns were fitted on gunboats.[20] The gun was not accepted by the American Army until 1866 when a sales representative of the manufacturing company demonstrated it in combat.[10]

On July 17, 1863, Gatling guns were purportedly used to overawe New York anti-draft rioters.[21] Two were brought by a Pennsylvania National Guard unit from Philadelphia to use against strikers in Pittsburgh.

Gatling guns were famously not used at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as "Custer's Last Stand", when Gen. George Armstrong Custer chose not to bring Gatling Guns with his main force.

In April 1867, a Gatling gun was purchased for the Argentine Army by minister Domingo F. Sarmiento under instructions from president Bartolomé Mitre.[22]

Captain Luis Germán Astete of the Peruvian Navy took with him dozens of Gatling guns from the United States to Peru in December 1879 during the Peru-Chile War of the Pacific. Gatling guns were used by the Peruvian Navy and Army, especially in the Battle of Tacna (May 1880) and the Battle of San Juan (January 1881) against the invading Chilean Army.

Lieutenant Arthur L. Howard of the Connecticut National Guard had an interest in the company manufacturing Gatling guns and took a personally owned Gatling gun to Saskatchewan, Canada, in 1885 for use with the Canadian military against Métis rebels during Louis Riel's North-West Rebellion.[10]

Africa and Asia

The Gatling gun was used most successfully to expand European colonial empires by defeating indigenous warriors mounting massed attacks, including the Zulu, the Bedouin, and the Mahdists.[10] Imperial Russia purchased 400 Gatling guns and used them against Turkmen cavalry and other nomads of central Asia.[23] The British Army first deployed the Gatling gun in 1873-74 during the Anglo-Ashanti wars, and extensively during the latter actions of the 1879 Anglo-Zulu war.[24] The Royal Navy used Gatling guns during the 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War.[11]

Spanish–American War

Because of infighting within army ordnance, Gatling guns were used by the U.S. Army during the Spanish–American War.[25] A four-gun battery of Model 1895 ten-barrel Gatling guns in .30 Army, made by Colt's Arms Company, was formed into a separate detachment led by Lt. John "Gatling Gun" Parker.[26] The detachment proved very effective, supporting the advance of American forces at the Battle of San Juan Hill. Three of the Gatlings with swivel mountings were used with great success against the Spanish defenders.[3] During the American charge up San Juan and Kettle hills, the three guns fired a total of 18,000 .30 Army rounds in 8 1⁄2 minutes (an average of over 700 rounds per minute per gun of continuous fire) against Spanish troop positions along the crest of both hills, wreaking terrible carnage.[3][27]

Despite this remarkable achievement, the Gatling's weight and cumbersome artillery carriage hindered its ability to keep up with infantry forces over difficult ground, particularly in Cuba, where roads were often little more than jungle footpaths. By this time, the U.S. Marines had been issued the modern tripod-mounted M1895 Colt–Browning machine gun using the 6mm Lee Navy round, which they employed to defeat the Spanish infantry at the battle of Cuzco Wells.

Philippine-American War

Gatling guns were used by the U.S. Army during the Philippine–American War.

One such instance was during the Battle of San Jacinto (1899) (Spanish: Batalla de San Jacinto) which was fought on November 11, 1899, in San Jacinto in the Philippines, between Philippine Republican Army soldiers and American troops.[28]

The Gatling's weight and artillery carriage hindered its ability to keep up with American troops over uneven terrain, particularly in the Philippines, where outside the cities there were heavily foliaged forests and steep mountain paths.

Further development

After the Gatling gun was replaced in service by newer recoil or gas-operated weapons, the approach of using multiple externally powered rotating barrels fell into disuse for many decades. However, some examples were developed during the interwar years, but only existed as prototypes or were rarely used. The concept resurfaced after World War II with the development of the Minigun and the M61 Vulcan. Many other versions of the Gatling gun were built from the late 20th century to the present, the largest of these being the 30mm GAU-8 Avenger autocannon as used on the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II.

Current usage favors mounted guns, either vehicular or emplaced, where the fire rate necessitates multiple barrels to space out the use of each to avoid melting a single barrel at full auto fire. These guns are not able to be fired by humans, and attempting to do so can be fatal as the rotational force from the extremely rapid rotation of modern miniguns throws the gun at the user if it is not secured.

See also

- Agar gun

- Centrifugal gun

- Gorgas machine gun

- Puckle gun

- List of multiple barrel firearms

References

- Weight listed for Colt's Model 1877 10-barrel gun, w/o carriage or mount.

- "Gatling Gun – Facts & Summary". history.com. Archived from the original on 2016-02-24.

- Parker, John H. (Lt.), The Gatlings At Santiago, Middlesex, UK: Echo Library (reprinted 2006)

- Chambers, John W. (II) (2000). "San Juan Hill, Battle of". The Oxford Companion to American Military History. HighBeam Research Inc. Archived from the original on 2009-11-26. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

- 1884 Picture of Gatling Gun on board 1875 US warship "Alliance"

- U.S. Ordnance Dept., Handbook of the Gatling Gun, Caliber .30 Models of 1895, 1900, and 1903, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, (1905) p. 21

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2010-09-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Wahl and Toppel, 1971, p. 155

- Greeley, Horace; Leon Case (1872). The Great Industries of the United States. J.B. Burr & Hyde. p. 944. ISBN 978-1-85506-627-4.

- Emmott, N.W. "The Devil's Watering Pot" United States Naval Institute Proceedings September 1972 p. 70.

- Emmott, N.W. "The Devil's Watering Pot" United States Naval Institute Proceedings September 1972 p. 72.

- Richard J. Gatling, "Improvement in revolving battery-guns," Archived 2017-01-20 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Patent No. 36,386 (issued: Nov. 4, 1862).

- Paul Wahl and Don Toppel, The Gatling Gun, Arco Publishing, 1971.

- Paul Wahl and Don Toppel, The Gatling Gun, Arco Publishing, 1971, p. 155.

- Randolph, Captain W. S., 5th US Artillery Service and Description of Gatling Guns, 1878 Archived 2016-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Friedman, Norman (1984). U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 457–463. ISBN 978-0-87021-718-0.

- History of Accles & Shelvoke from company website

- American Ordnance Company (1896). The Driggs-Schroeder System of rapid-fire guns, 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: The Deutsch Lithographing and Printing Company. pp. Preface, 76.

- Civil War Weapons And Equipment by Russ A. Pritchard Jnr.

- "The Gatling Gun In The Civil War". civilwarhome.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-25. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- Julia Keller, Mr. Gatling's Terrible Marvel (2008), p. 168-170

- Rauch, George v (1 January 1999). Conflict in the Southern Cone: The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute with Chile, 1870-1902. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96347-7.

- Emmott, N.W. "The Devil's Watering Pot" United States Naval Institute Proceedings September 1972 p. 71.

- Laband, John (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Zulu Wars. Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8108-6078-0.

- Patrick McSherry. "Gatling". spanamwar.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-09. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- Parker, John H. (Lt.), History of the Gatling Gun Detachment, Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co. (1898), pp. 20, 23–32

- Parker, John H.: Cranked by hand at its highest speed until the first magazine of ammunition had been emptied, the M1895 .30 Gatling Gun had an initial rate of fire of 800–900 rounds per minute.

- Linn, B.M., 2000, The Philippine War, 1899-1902, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0700612254

Further reading

- Ordnance Department, United States (1917). Handbook of the Gatling Gun, Caliber .30. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gatling gun. |

- Randolph, Captain W. S., 5th US Artillery Service and Description of Gatling Guns, 1878

- 19th Century Machine Guns

- List of Military Gatling & Revolver cannons

- Austro-Hungarian Gatling Guns

- U.S. Patent 36,836 -- Gatling gun

- U.S. Patent 47,631 -- improved Gatling gun

- U.S. Patent 112,138 -- revolving battery gun

- U.S. Patent 125,563 -- improvement in revolving battery guns

- U.S. Patent 110,338 -- feeder for repeating firearms

- Description of operating principle (with animation) from HowStuffWorks

- CGI animated GAU-17/A

- Animations and technical descriptions of 1862, 1865 and 1874 models (Requires QuickTime and not suitable for slow-speed links)

- Presentation by Keller about Mr. Gatling's Terrible Marvel: The Gun That Changed Everything and the Misunderstood Genius Who Invented It at the Printers Row Book Fair, June 8, 2008

- The Gatling Gun

- Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II