Geology of the Canary Islands

The geology of the Canary Islands is dominated by volcanic rock. The Canary Islands and some seamounts to the north-east form the Canary Volcanic Province whose volcanic history started about 70 million years ago.[1] The Canary Islands region is still volcanically active. The most recent volcanic eruption on land occurred in 1971 and the most recent underwater eruption was in 2011-12.[2]

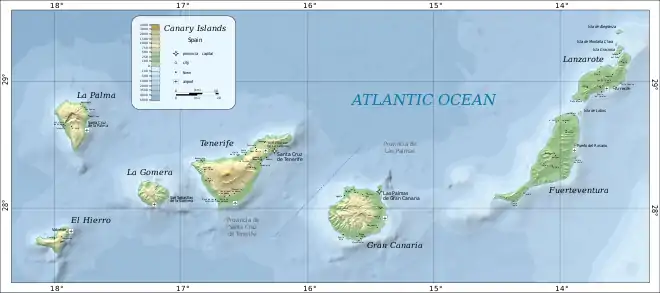

The Canary Islands are a 450 km (280 mi) long, east-west trending, archipelago of volcanic islands in the North Atlantic Ocean, 100–500 km (62–311 mi) off the coast of Northwest Africa.[3]

From east to west, the main islands are Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Gomera, La Palma, and El Hierro.[Note 1] There are also several minor islands and islets. The seven main Canary Islands originated as separate submarine seamount volcanoes on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, which is 1,000–4,000 m (3,300–13,100 ft) deep in the Canarian region.

Lanzarote and Fuerteventura are parts of a single volcanic ridge called the Canary Ridge. These two present-day islands were a single island in the past. Part of the ridge has been submerged and now Lanzarote and Fuerteventura are separate islands, separated by an 11 km (6.8 mi) wide, 40 m (130 ft) deep strait.[5]

Volcanic activity has occurred during the last 11,700 years on all of the main islands except La Gomera.[6]

Growth stages

Volcanic oceanic islands, such as the Canary Islands, form in deep parts of the oceans. This type of island forms by a sequence of development stages:[7]

- (1) submarine (seamount) stage

- (2) shield-building stage

- (3) declining stage (La Palma and El Hierro)

- (4) erosion stage (La Gomera)

- (5) rejuvenation/post-erosional stage (Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, Gran Canaria and Tenerife).[7]

The Canary Islands differ from other volcanic oceanic islands, such as the Hawaiian Islands, in several ways – for example, the Canary Islands have stratovolcanoes, compression structures and a lack of subsidence.[7]

The seven main Canary Islands originated as separate submarine seamount volcanoes on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Each seamount, built up by the eruption of many lava flows, eventually became an island. Subaerial volcanic eruptions continued on each island. Fissure eruptions dominated on Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, resulting in relatively subdued topography with heights below 1,000 m (3,300 ft). The other islands are much more rugged and mountainous. In the case of Tenerife, the volcanic edifice of Teide rises about 7,500 m (24,600 ft) above the ocean floor (about 3,780 m (12,400 ft) underwater and 3,715 m (12,188 ft) above sea level).[8][9]

Age

The age of the oldest subaerially-erupted lavas on each island decreases from east to west along the island chain: Lanzarote-Fuerteventura (20.2 Ma), Gran Canaria (14.6 Ma), Tenerife (11.9 Ma), La Gomera (9.4 Ma), La Palma (1.7 Ma) and El Hierro (1.1 Ma).[10]

Rock types

Volcanic rock types found on the Canary Islands are typical of oceanic islands. The volcanic rocks include alkali basalts, basanites, phonolites, trachytes, nephelinites, trachyandesites, tephrites and rhyolites.[7][11]

Outcrops of plutonic rocks (for example, syenites, gabbros and pyroxenites) occur on Fuerteventura,[12] La Gomera and La Palma. Apart from some islands of Cape Verde (another island group in the Atlantic Ocean, about 1,400 km (870 mi) south-west of the Canary Islands), Fuerteventura is the only oceanic island known to have outcrops of carbonatite.[13]

Volcanic landforms

Examples of the following types of volcanic landforms occur in the Canary Islands: shield volcano, stratovolcano, collapse caldera, erosion caldera, cinder cone, coulee, scoria cone, tuff cone, tuff ring, maar, lava flow, lava flow field, dyke, volcanic plug.[14]

Cause

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the volcanism of the Canary Islands.[15] Two hypotheses have received the most attention from geologists: (1) the volcanism is related to crustal fractures extending from the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, and (2) the volcanism is caused by the African Plate moving slowly over a hotspot in the Earth's mantle. Currently, a hotspot is the explanation accepted by most geologists who study the Canary Islands.[16]

Notes

- Since 2018, La Graciosa has been officially designated "la octava isla canaria habitada"[4] (the eighth inhabited island of the Canary Islands), in effect the eighth "main island". This is only a political and social designation. La Graciosa continues to be a geologically minor island of the Canary Islands, associated with its much larger neighbour Lanzarote.

References

- Carracedo, J.C.; Troll, V.R.; Zaczek, K.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Soler, V.; Deegan, F.M. (2015) The 2011–2012 submarine eruption off El Hierro, Canary Islands: New lessons in oceanic island growth and volcanic crisis management, Earth-Science Reviews, volume 150, pages 168–200, doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.06.007

- Carracedo, J.C.; Troll, V.R.; Zaczek, K.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Soler, V.; Deegan, F.M. (2015) The 2011–2012 submarine eruption off El Hierro, Canary Islands: New lessons in oceanic island growth and volcanic crisis management, Earth-Science Reviews, volume 150, pages 168–200, doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2015.06.007

- Schmincke, H.U. and Sumita, M. (1998) Volcanic Evolution of Gran Canaria reconstructed from Apron Sediments: Synthesis of VICAP Project Drilling in Weaver, P.P.E., Schmincke, H.U., Firth, J.V., and Duffield, W. (editors) (1998) Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, volume 157

- "El Senado reconoce a La Graciosa como la octava isla canaria habitada". El País (in Spanish). 26 June 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Carracedo, J.C. and Troll, V.R. (2016) The Geology of the Canary Islands, Amsterdam, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-12-809663-5, page 532

- Tanguy, J-C. and Scarth, A. (2001) “Volcanoes of Europe”, Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-03-3, page 101

- Viñuela, J.M. (2007). "The Canary Islands Hot Spot" (PDF). www.mantleplumes.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J.C. Canary Islands, Geology in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) Encyclopedia of Islands, page 134

- Martínez-García, E. Spain in Moores, E.M. and Fairbridge, R. (editors) (1997) Encyclopedia of European and Asian Regional Geology, London, Chapman and Hall, ISBN 0-412740-400, page 680

- Carracedo, J.C and Troll, V.R. (editors) (2013) “Teide Volcano:Geology and Eruptions of a Highly Differentiated Oceanic Stratovolcano”, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-642-25892-3, Page 24

- Tanguy, J-C. and Scarth, A. (2001) “Volcanoes of Europe”, Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-03-3, page 101

- Hoernle, K. and Carracedo, J.C. Canary Islands, Geology in Gillespie, R. and Clague, D. (editors) (2009) Encyclopedia of Islands, page 140

- Bell, K. and Tilton, G.R. (2002) Probing The Mantle: The Story From Carbonatites, EOS, Volume 83, Number 25, pages 273-280 https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2002EO000190

- Tanguy, J-C. and Scarth, A. (2001) Volcanoes of Europe. Harpenden, Terra Publishing, ISBN 1-903544-03-3, page 100

- Vonlanthen, P., Kunze, K., Burlini, L. and Grobety, B. (2006) Seismic properties of the upper mantle beneath Lanzarote (Canary Islands): Model predictions based on texture measurements by EBSD, Tectonophysics, volume 428, pages 65-85, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2006.09.005

- Yepes, J.A. (2007). "The Canary Islands Topobathymetric Relief Map - Aspect Of The Sea Bed And Geology" (PDF). Spanish Institute of Oceanography (IEO). Retrieved 25 July 2018.