Phonolite

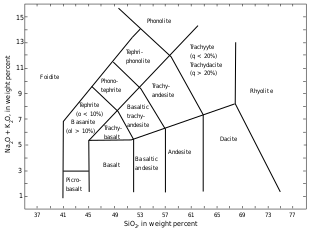

Phonolite is an uncommon extrusive rock, of intermediate chemical composition between felsic and mafic, with texture ranging from aphanitic (fine-grain) to porphyritic (mixed fine- and coarse-grain). Its intrusive equivalent is nepheline syenite.

| Extrusive igneous rock | |

| |

| Composition | |

|---|---|

| Primary | nepheline, sodalite, hauyne, leucite, analcite, sanidine, anorthoclase |

| Secondary | biotite, amphibole, pyroxene, olivine |

The name phonolite comes from the Ancient Greek meaning "sounding stone" because of the metallic sound it produces if an unfractured plate is hit; hence the English name clinkstone.

Formation

Unusually, phonolite forms from magma with a relatively low silica content, generated by low degrees of partial melting (less than 10%) of highly aluminous rocks of the lower crust such as tonalite, monzonite and metamorphic rocks. Melting of such rocks to a very low degree promotes the liberation of aluminium, potassium, sodium and calcium by melting of feldspar, with some involvement of mafic minerals. Because the rock is silica-undersaturated, it has no quartz or other silica crystals, and is dominated by low-silica feldspathoid minerals more than feldspar minerals.

A few geological processes and tectonic events can melt the necessary precursor rocks to form phonolite. These include intracontinental hotspot volcanism,[1] such as may form above mantle plumes covered by thick continental crust. A-type granites and alkaline igneous provinces usually occur alongside phonolites. Low-degree partial melting of underplates of granitic material in collisional orogenic belts may also produce phonolites.

Mineralogy and petrology

Phonolite is a fine-grained equivalent of nepheline syenite. They are products of partial melting, are silica-undersaturated, and have feldspathoids in their normative mineralogy.

Mineral assemblages in phonolite occurrences are usually abundant feldspathoids (nepheline, sodalite, hauyne, leucite and analcite) and alkali feldspar (sanidine, anorthoclase or orthoclase), and rare sodic plagioclase. Biotite, sodium-rich amphiboles and pyroxenes along with iron-rich olivine are common minor minerals. Accessory phases include titanite, apatite, corundum, zircon, magnetite and ilmenite.[3]

Blairmorite is an analcite-rich variety of phonolite.[4][5]

Occurrence

Nepheline syenites and phonolites occur widely distributed throughout the world[6] in Canada, Norway, Greenland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the Ural Mountains, the Pyrenees, Italy, Eifel and Kaiserstuhl in Germany, Brazil, the Transvaal region, the Magnet Cove igneous complex of Arkansas, the Beemerville Complex of New Jersey,[7] as well as on oceanic islands such as the Canary Islands.[8]

Nepheline-normative rocks occur in close association with the Bushveld Igneous Complex, possibly formed from partial melting of the wall rocks adjacent to that large ultramafic layered intrusion. Phonolite occurs in the related Pilanesberg Complex and Pienaars River Complex.[9]

Examples

- Devils Tower, Wyoming, United States, an example of columnar-jointed phonolite[10]

- Missouri Buttes, Crook County, northeast Wyoming, United States

- Dunedin, New Zealand[11]

- Bořeň, northwestern Czech Republic

- Hoodoo Mountain, northwestern British Columbia, Canada

- Jebel Nefusa, Libya[12]

- Teide, a stratovolcano on the island of Tenerife[13]

- Mont Gerbier de Jonc, Ardèche, France[14]

- The phonolitic lava lake in Mount Erebus, Ross Island, Antarctica

- Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine phonolite pipe

- Montiferru, Sardinia

- Wolf Rock, Cornwall

- Bass Rock, North Berwick Law and Traprain Law in southeast Scotland, UK[15]

- The 'Bellstone' in Saint Helena[16]

Economic importance

Phonolites can be of interest as dimension stone or as aggregate for gravels.

Rarely, economically mineralised phonolite-nepheline syenite alkaline complexes can be associated with rare-earth mineralisation, uranium mineralisation and phosphates, such as at Phalaborwa, South Africa.

Phonolite tuff was used as a source of flint for adze heads and such by prehistoric people from Hohentwiel and Hegau, Germany.[17]

Phonolites can be separated into slabs of appropriate dimensions to be used as roofing tiles in place of roofing slate. One such occurrence is in the French Massif Central region such as the Haute Loire département.

References

- Wiesmaier, Sebastian; Troll, Valentin R.; Carracedo, Juan Carlos; Ellam, Robert M.; Bindeman, Ilya; Wolff, John A. (2012-12-01). "Bimodality of Lavas in the Teide–Pico Viejo Succession in Tenerife—the Role of Crustal Melting in the Origin of Recent Phonolites". Journal of Petrology. 53 (12): 2465–2495. doi:10.1093/petrology/egs056. ISSN 0022-3530.

- Ridley, W. I., 2012, Petrology of Igneous Rocks, Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide Occurrence Model, USGS Scientific Report 2010-5070-C, Chapter 15.

- Blatt, Harvey and Robert J. Tracy, Petrology, Freeman, 2nd ed. 1996, p. 52, ISBN 0-7167-2438-3.

- Peterson, T.D.; Currie, K.L. (1993). Analcite-bearing igneous rocks from the Crowsnest Formation, southwestern Alberta (Current Research report 93-B1) (PDF). Geological Survey of Canada. pp. 51–56.

- Deer, W.A.; Howie, R.A.; Zussman, J. (2013). An Introduction to the Rock-Forming Minerals (3rd edition). London: Mineralogical Society. ISBN 9780903056274.

- Woolley, A.R., 1995. Alkaline rocks and carbonatites of the world., Geological Society of London.

- Eby, G. N., 2012, The Beemerville alkaline complex, northern New Jersey, in Harper, J. A., ed., Journey along the Taconic unconformity, northeastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and southeastern New York: Guidebook, 77th Annual Field Conference of Pennsylvania Geologists, Shawnee on Delaware, PA, p. 85-91.

- Bryan, S. E; Cas, R. A. F.; Martı́, J (May 1998). "Lithic breccias in intermediate volume phonolitic ignimbrites, Tenerife (Canary Islands): constraints on pyroclastic flow depositional processes". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 81 (3–4): 269–296. Bibcode:1998JVGR...81..269B. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(98)00004-3.

- Pirajno, Franco (1992). Hydrothermal Mineral Deposits: Principles and Fundamental Concepts for the Exploration Geologist. Berlin: Sringer-Verlag. pp. 267–269. ISBN 978-3-642-75673-3.

- Bassett, W. A. (October 1961). "Potassium-Argon Age of Devils Tower, Wyoming". Science. 134 (3487): 1373. Bibcode:1961Sci...134.1373B. doi:10.1126/science.134.3487.1373. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17807346.

- Marshall, Patrick, 'The occurrence of a mineral hitherto unknown in the phonolites of Dunedin, New Zealand', 1929.

- Bausch, W. M. (June 1978). "The central part of the Jebel Nefusa volcano (Libya) survey map, age relationship and preliminary results". Geologische Rundschau. 67 (2): 389–400. Bibcode:1978GeoRu..67..389B. doi:10.1007/BF01802796.

- Ablay, G. J.; Carroll, M. R.; Palmer, M. R.; Marti, J.; Sparks, R. S. J. (May 1998). "Basanite-Phonolite Lineages of the Teide-Pico Viejo Volcanic Complex, Tenerife, Canary Islands". Journal of Petrology. 39 (5): 905–936. Bibcode:1998JPet...39..905A. doi:10.1093/petroj/39.5.905.

- "Gerbier de Jonc et sources de la Loire". Volcans des sucs (in French). Geopark - Parc Naturel Régional des Monts d'Ardèche. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- BGS map viewer http://mapapps.bgs.ac.uk/geologyofbritain/home.html

- https://sainthelenaisland.info/levelwood.htm#bellstone

- Affolter, J., 2002, Provenance des silex préhistoriques du Jura et des régions limitrophes, Archéologie neuchâteloise, 28.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phonolite. |