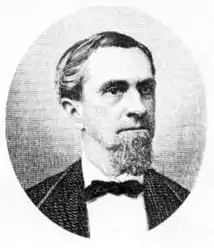

George Davis (American politician)

George Davis (March 1, 1820 – February 23, 1896) was a Confederate politician and railroad counsel who served as Attorney General of the Confederate States for 480 days in 1864 and 1865.

George Davis | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th Confederate States Attorney General | |

| In office January 2, 1864 – April 26, 1865 | |

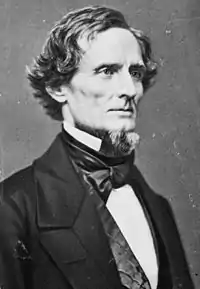

| President | Jefferson Davis |

| Preceded by | Wade Keyes (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Position Abolished |

| Confederate States Senator from North Carolina | |

| In office February 18, 1862 – January 2, 1864 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Edwin Reade |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 1, 1820 Wilmington, North Carolina |

| Died | February 23, 1896 (aged 75) Wilmington, North Carolina |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Whig Party (until 1856), Constitutional Union Party (1860) |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill |

A skilled orator, he gave a notable public speech in March 1861 in which he argued that North Carolina should secede from the United States of America to protect the private economic interest in chattel slavery.

Biography

Early years

George Davis was born on his father's slave plantation at Porter's Neck, near Wilmington, North Carolina. He attended the University of North Carolina and was valedictorian of its Class of 1838. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1840.

In 1848, he became general counsel of the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad, a highly remunerative position that he held until the end of his life.[1]

1861 peace efforts

Davis began his political career as a Whig. The party collapsed in 1856. With other Southern former Whigs who opposed secession but who had declined to become Republicans or Democrats, he backed the Constitutional Union Party in the Election of 1860.

Following the election of Abraham Lincoln, Davis continued to pursue the idea of negotiated political peace. He served as a delegate from North Carolina to the Washington Peace Conference of February 4–27, 1861.

Davis reacted badly to the discussion of proposed compromise constitutional amendments that would have preserved slavery where it existed but also prohibited slavery in any territory of the United States "now held, or hereafter acquired" north of the latitude 36 degrees, 30 minutes line.[2]

He returned to Wilmington a secessionist.

Slavery and Secession

On March 2, 1861 — just days after returning to Wilmington from the peace conference — Davis made a public speech in which he spoke of North Carolina's requirement of "property in slaves."

He made clear publicly that he was a secessionist. Secession, he said, was required to protect the economic interests of North Carolina's slaveowners and all others in the state economically intertwined with the institution of slavery:

"We could never accept the plan adopted by the Convention as consistent with the rights, the interests, or the dignity of North Carolina ... The division must be made on the line of slavery. The state must go with the South."[3]

North Carolina's white political elites declared secession from the Union on May 20, 1861, and the state's formal involvement with the confederate government began. Soon after, North Carolina secessionists placed Davis on a slate from which he was chosen a delegate to the Provisional Confederate Congress for 1861-1862. Later, Davis was elected to a two-year term in the Senate.

Confederate politics

On Sept. 27, 1863, Davis's wife, Mary Adelaide Polk Davis (of the politically prominent Polk Family, of which former President Polk had been a member) died in Wilmington, aged 43.[4] Later that autumn, the North Carolina General Assembly elected William Alexander Graham to the Senate seat held by Davis.

To keep George Davis in the foundering government, Confederate President Jefferson Davis (no known relation) in January 1864 appointed him as Attorney General ahead of the end of George Davis's senate term ending on February 17, 1864.

George Davis resigned the senate and then held the cabinet post from January 2, 1864. The duties of Confederate attorney general did not involve any part of military affairs. And, as the Confederate Supreme Court was never created, there was little for the attorney general to do other than attend cabinet deliberations and to draft legal guidance for other cabinet members based on the thin book of Confederate statutes. Davis served in the post until his resignation soon after the Fall of Richmond in April 1865.

Despite many offers of public service made to him before and after the war, George Davis never held any public office under the flag of the United States of America.

Fugitive and prisoner

As the Confederacy collapsed, George Davis accompanied the fugitive government as far as Charlotte, North Carolina. He submitted a resignation on April 25, 1865, and received notice of its acceptance the next day. He had served as attorney general for 68 weeks and three days.

Davis then, traveling alone, attempted to flee to England by way of Florida and Nassau. As he planned to leave the United States, he chose to let his motherless children remain in extended family.

Davis was captured by United States forces at Key West, Florida, on October 18, 1865. He was imprisoned at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, New York until being given his parole on January 2, 1866.

Later life

Davis accepted an appointment as a delegate to the 1866 National Union Convention. The private convention, ultimately unsuccessful, was an attempt to build a new political party to support President Andrew Johnson and his personal policies of white supremacy and administrative vandalism of Congress's program of Reconstruction.

Davis returned to Wilmington. He rebuilt his law practice and worked as a railroad counsel. Davis married Monimia Fairfax, 17 years his junior and a member of Virginia's elite and powerful Fairfax and Randolph families.[5]

In 1878, Governor Zebulon Baird Vance offered Davis the chief justiceship of the state supreme court, but Davis turned it down on the grounds that he could not live on the salary.

He gave his last public speech in 1889, at a memorial event in Wilmington for Jefferson Davis. In the speech, George Davis summarized his own political career in a sentence:

"My ambition went down with the banner of the South, and, like it, never rose again."[6]

He died in 1896, aged 75.

Memorials

Lost Cause Encomiums

After his death, white Wilmington elites and leaders of the state's legal profession began to lionize Davis as an example of perfect white Southern manhood.

During this period — and despite Davis's real history as a pro-Union Whig and as a footnote figure in the American Civil War — Lost Cause proponents created a fictional, revisionist image of Davis as an ideal statesman.

For example, during a speech upon the presentation of his portrait to the Supreme Court of North Carolina in the autumn of 1915, Confederate veteran and revisionist Lost Cause pamphleteer Samuel A'Court Ashe described Davis as a man without a single character fault or sin — even extending his over-the-top praise to Davis' handwriting:

Indeed, his very handwriting was an index of that characteristic, every letter being perfectly formed, and his writing without blemish.[7]

Monument

In 1911, a Confederate monument to Davis was dedicated in downtown Wilmington, North Carolina, by the United Daughters of the Confederacy — 46 years after the Confederacy's surrender.

The monument shows Davis, hand on lectern, giving a speech. Its stone base includes a spurious encomium to Davis's supposed virtue, not dissimilar from the Lost Cause memorial speeches given about him during the era.

Historians have stated that similar monuments are evidence of a wide effort by the UDC and others, long after the failure of the Confederacy, to insert the false Lost Cause Narrative into the cultural memory, announce to nonwhites the final defeat of Reconstruction, and to support white supremacy.[8]

On June 25, 2020, the statue, but not its pedestal, was temporarily removed by the City of Wilmington coincident with the firing of three police officers the city said had participated in "brutally racist" discussions recorded on official police equipment. To justify the dismantling, the city government cited the public safety exception within the state law intended to frustrate the removal of confederate monuments in North Carolina. The city did not announce a place of storage or a date for re-erection.[9]

Grave Marker

After his death in 1896, his remains are buried in Wilmington's Oakdale Cemetery under a flat stone marker that bears a Celtic cross.[10]

The marker includes the revisionist Lost Cause inscription —

"Statesman, yet friend to truth of soul sincere

In action faithful and in honor, dear"

Highway historical marker

In 1949, the North Carolina state government placed a highway historical marker regarding Davis on US Highway 17 at Porters Neck Road near Wilmington.:[12]

GEORGE DAVIS

1820-1896

Served the Confederacy

as a senator, 1862-64, &

as the attorney general,

1864-65. His birthplace

was three miles east.

Liberty Ship

In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS George Davis was named in his honor. It was scrapped in 1960.[13]

Portrait

During the court's Fall Term of 1915, his family presented a portrait of George Davis to hang in the library of the Supreme Court of North Carolina. All other portraits in the court's collection are of justices of the court.[14]

Sons of Confederate Veterans Unit

A unit of the Sons of Confederate Veterans was named "George Davis Camp 5."[15]

References

- Buck Yearns. "Davis, George". ncpedia.org. State Library of North Carolina.

- "Amendments Proposed in Congress by Senator John J. Crittenden: December 18, 1860". Avalon Project.

- Buck Yearns. "Davis, George". ncpedia.org. State Library of North Carolina.

- "Mary Adelaide Polk Davis (1820-1863)". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- "Monimia Fairfax Davis". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Edwin Anderson Alderman; Joel Chandler Harris; Charles W. Kent; Charles Alphonso Smith; Lucian Lamar Knight (1909). "Library of Southern Literature, Volume 3". Google Books. Martin and Hoyt Company. p. 1227. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "Presentation of the Portrait of Hon. George Davis to the Supreme Court of North Carolina by Samuel A'Court Ashe" (PDF). nccourts.gov. North Carolina Judicial Branch. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

I have been asked by the family of George Davis to present his portrait to the Supreme Court and to request that it may take its place on your walls in company with those of the other distinguished men who have adorned the Bench and Bar of this high Court. As great as the honor is to have one's portrait preserved here, but few have been more worthy of it than the most illustrious son of the Cape Fear, whose memory is an inheritance of the State and whose career and walk in life present a study at once attractive and profitable. Davis was a thorough Carolinian - the evolution of conditions on the Cape Fear River.

- RVA Magazine. "Monument Avenue and the Insidiously Seductive Lost Cause Narrative." https://rvamag.com/news/community/monument-avenue-and-the-insidiously-seductive-lost-cause-narrative.html

- WECT. "Two confederate Statues Removed from Downtown Wilmington." https://www.wect.com/2020/06/25/breaking-confederate-statues-removed-downtown-wilmington/

- "George Davis". Findagrave.com. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "Detail photo of George Davis grave marker". Findagrave.com. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "Marker D-36: "George Davis"". North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- "Liberty Ships – Part 2: EMC #s 768 thru 1551". shipbuildinghistory.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- "Portrait Presentations". nccourts.gov. North Carolina Judicial Branch. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

Chief Justice CLARK said: North Carolina and our profession will always revere the memory of Mr. Davis. He was a lawyer of the highest ability, a patriot without personal ends to serve, and a citizen whose character was without spot. His portrait is most welcome to these halls, and the Marshal will hang it in its appropriate place in the Library of the Court.

- Todd Volkstorf (February 17, 2002). "Refurbished Davis statue again stands downtown". Wilmington, North Carolina: Wilmington Star-News. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

"To have a senator and attorney general from your hometown is a pretty big deal," said Jimmie Davis, of the local Sons of Confederate Veterans chapter: George Davis Camp No. 5.

Further reading

- Patrick, Rembert W. (1944). Jefferson Davis and His Cabinet. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 104–120.

External links

- "George Davis". Find a Grave. Retrieved April 14, 2009.