Constitutional Union Party (United States)

The Constitutional Union Party was a United States third party active during the 1860 elections. It consisted of conservative former Whigs, largely from the Southern United States, who wanted to avoid secession over the slavery issue and refused to join either the Republican Party or the Democratic Party. The Constitutional Union Party campaigned on a simple platform "to recognize no political principle other than the Constitution of the country, the Union of the states, and the Enforcement of the Laws".

Constitutional Union Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader | John J. Crittenden John Bell |

| Founded | 1860 |

| Dissolved | 1861 |

| Preceded by | Whig Party American Party Opposition Party |

| Merged into | Unionist Party |

| Headquarters | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Ideology | Conservatism Southern unionism |

| Colors | Orange |

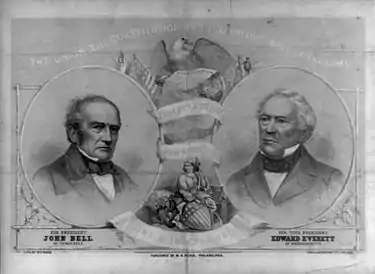

The Whig Party had collapsed in the 1850s due to a series of sectional crises over slavery. Though some former Whigs joined the Democratic Party or the new, anti-slavery Republican Party, others joined the nativist American Party. The American Party entered a period of rapid decline following the 1856 elections, and in the lead-up to the 1860 elections John J. Crittenden and other former Whigs founded the Constitutional Union Party. The 1860 Constitutional Union Convention met in May 1860, nominating John Bell of Tennessee for president and Edward Everett of Massachusetts for vice president. Party leaders hoped to force a contingent election in the House of Representatives by denying any one candidate a majority in the Electoral College.

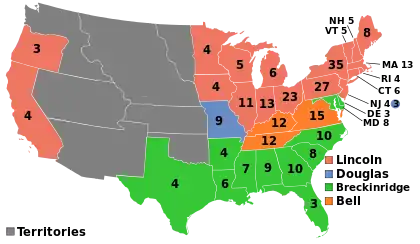

The 1860 election essentially consisted of two campaigns, as Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln competed with Northern Democratic candidate Stephen A. Douglas in the North, and Bell competed with Southern Democratic candidate John C. Breckinridge in the South. Ultimately, Lincoln won the election by winning nearly every Northern electoral vote. Bell took 12.6% of the nationwide popular vote, carried three states in the Upper South, and finished with the second highest vote total in each remaining slave state that held a popular vote. After the election, Crittenden and other Constitutional Unionists unsuccessfully sought to prevent a civil war with the Crittenden Compromise and the Peace Conference of 1861. Bell declared his support for the Confederacy following the Battle of Fort Sumter, but many other Constitutional Unionists remained loyal to the Union throughout the American Civil War.

Background

The Constitutional Union Party had its roots in the Whig Party and the sectional crises of the 1850s. The Compromise of 1850 shook up partisan alignments in the South, with elections being contested by unionists and extremist "Fire-Eaters" rather than Whigs and Democrats. The victory of pro-compromise Southern politicians in these elections, along with President Millard Fillmore's attempts at diligently enforcing the Fugitive Slave Clause, temporarily quieted Southern calls for secession.[1] The debate over the Kansas–Nebraska Act again polarized legislators sectional lines, with Southern Whigs providing critical votes in the House as a narrow majority of Northern Democrats voted against it.[2] A new, anti-slavery party known as the Republican Party was formed in May 1854.[3] Republican leaders, including Abraham Lincoln, generally did not call for the abolition of slavery, but instead called for Congress to prevent the extension of slavery into the territories.[4] By 1855, Republicans had replaced the Whigs as the main opposition to the Democrats in most Northern states. The nativist American Party displaced the Whigs in the remaining states; though some Democrats joined the American Party, in many Southern states the American Party consisted almost entirely of former Whigs.[5]

The 1856 American National Convention nominated former President Fillmore for president in the 1856 presidential election; Fillmore also received the presidential nomination at the sparsely attended 1856 Whig National Convention.[6] Many supporters of the American Party continued to identify primarily as Whigs,[7] and Fillmore minimized the issue of nativism, instead attempting to use his campaign as a platform for unionism and a revival of the Whig Party.[8] He finished in second in several states in the South and carried just a single state in the 1856 election, confirming that the Republican Party, rather than the American Party, would replace the Whigs as the main opposition to the Democrats.[9] The American Party collapsed after the 1856 elections, and many Southern officeholders who refused to join the Democratic Party organized themselves into the Opposition Party.[10]

Formation

Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky, Henry Clay's successor in border-state Whiggery, led a group of conservative, unionist congressmen in forming the Constitutional Union Party.[11] At Crittenden's behest, fifty former and current members of Congress met in Washington, D.C. in December 1859, where they agreed to form a new party dedicated to preserving the union and avoiding debates over slavery.[12] The new party received the blessing of the respective national committees of the Whig Party and the American Party,[13] and was officially formed on February 12, 1860.[14]

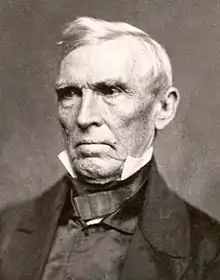

Among the members of the new party's executive committee were Crittenden, former Democratic Senator William Cabell Rives of Virginia, 1852 Whig vice presidential nominee William Alexander Graham of North Carolina, former Congressman John P. Kennedy of Maryland, and newspaper editor William Gannaway Brownlow of Tennessee.[12] In the North, the party drew support from conservative former Whigs like Edward Everett and Robert Charles Winthrop.[15] Many of these Northerners, including Everett, were followers of Daniel Webster, a Whig senator from Massachusetts who had died in 1852.[16]

Party leaders did not expect to win the election outright, but instead sought to win states in the Upper South and the Lower North.[17] They were particularly focused on Maryland, the lone state won by Fillmore in 1856, as well as Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.[18] Constitutional Unionists hoped to deny an electoral vote majority to any one candidate, thereby forcing a contingent election in the House of Representatives.[17] Party leaders hoped that, in such a contingent election, the House would reject the other eligible candidates as too extreme and instead elect the Constitutional Union nominee.[19][lower-alpha 1]

National convention

The Constitutional Union national convention convened on May 9, 1860. Delegates came from 23 of the 33 states,[20] though the vast majority of delegates came from the Upper South.[21] As a large proportion of the delegates were over the age of sixty, some political opponents derided the Constitutional Unionists as the "Old Gentleman's Party". The party adopted a simple platform, stating that they would "recognize no political principle other than the Constitution...the Union...and the Enforcement of the Laws."[17] The party also established the National Central Executive Union Committee to wage the party's election campaign; Congressman Alexander Boteler of Virginia was selected to head the committee.[22]

Though the septuagenarian Crittenden was the acknowledged party leader, he declined to seek the presidential nomination due to his age. The two major contenders for the presidential nomination were former Senator John Bell of Tennessee and Governor Sam Houston of Texas. During his long career in the Whig Party, Bell had established a reputation as a moderate on the slavery issue, opposing both the Mexican–American War and the Kansas–Nebraska Act.[23] Houston had served in two wars and had compiled a long political record as a leading member of the Democratic Party, and like Bell he had opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act. However, his status a former protege of Andrew Jackson alienated many of the delegates, and Bell's backers argued that Houston would have little appeal in the North.[24] Aside from Bell and Houston, other potential candidates for the Constitutional Union presidential nomination included Everett, 1852 Whig nominee Winfield Scott, and Edward Bates of Missouri, who ultimately chose to support the Republican Party.[25]

On the first presidential ballot, Bell won 68 1/2 votes compared to Houston's 57, with the remainder of the delegates voting for Crittenden, Everett, and various favorite son candidates. Bell picked up support from dozens of delegates on the second ballot, thereby clinching the nomination.[26] Houston refused to endorse Bell and ultimately declined to back any candidate in the 1860 election.[27] Seeking to provide sectional balance to the ticket, the convention selected Everett as the party's vice presidential nominee by acclamation.[23] Everett reluctantly accepted the vice presidential nomination, as he felt that he had had a more accomplished career than Bell.[28] With the nomination of two former Whigs, many regarded the Constitutional Union Party as a continuation of the Whig Party; one Southern newspaper called the new party the "ghost of the old Whig Party."[29]

1860 presidential election

A split in the Democratic Party led to the nomination of two separate Democratic presidential candidates; Senator Stephen A. Douglas had the support of most Northern Democrats, while Vice President John C. Breckinridge garnered the backing of most Southern Democrats.[17] Meanwhile, seeking to rally support in the Deep South, a group of Constitutional Unionists meeting in Alabama issued a platform holding that Congress and territorial legislatures could not prevent individuals from bringing slaves into the territories. This platform, though not adopted by the national party, badly damaged the standing of Constitutional Unionists in the North.[30] Bell's ownership of slaves further alienated Northerners, and his and Everett's status as former Whigs limited the party's ability to compete for the support of Northern Democrats.[31] Thus, the 1860 presidential election essentially consisted of two separate campaigns. In the North, Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln faced Douglas, and in the South, the Constitutional Union ticket competed against Breckinridge.[17]

Adhering to precedent, Bell remained at his home during the campaign, but Breckinridge and other party leaders gave numerous speeches.[32] The party campaigned on the slogan, "the Union as it is, the Constitution as it is."[33] The party's official lack of a stance on slavery positioned it between the Lincoln's Republican Party, who campaigned on a platform against extending slavery to any new states or territories, and Breckinridge's Southern Democrats, who favored allowing slavery in all territories.[34] Historian Frank A. Towers writes that, "notwithstanding the nuances of local issues in selecting a president, voters could either endorse the compromise vision of the Union by choosing Douglas or Bell, or reject it by opting for Lincoln or Breckinridge."[35][lower-alpha 2] Southern Democrats attacked the Constitutional Union platform, arguing that the issue of slavery could not be ignored in the campaign.[17] Constitutional Unionists responded by attacking Breckinridge (who publicly disavowed disunion) as a secessionist who had fallen under the influence of Fire-Eaters like William Lowndes Yancey.[32] The party also attacked Lincoln as an inexperienced, sectional candidate whose election threatened to provoke the secession of the South.[36]

Recognizing Lincoln's likelihood of winning the election, some opponents of the Republican Party discussed the possibility of Bell, Breckinridge, and Douglas dropping out in favor of a new candidate, but Douglas and possibly Bell objected to this scheme.[37] In August, August Belmont, the chairman of Douglas's campaign, proposed an "entente cordiale" with the intent of denying Lincoln an electoral vote majority. After much negotiation, Douglas, Bell, and Breckinridge agreed to form a single fusion ticket in the state of New York. In the event of a fusion victory in the state, Douglas would receive eighteen electoral votes, Bell would receive ten electoral votes, and Breckinridge would receive seven electoral votes.[38] Similar fusion tickets were established in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Rhode Island.[39]

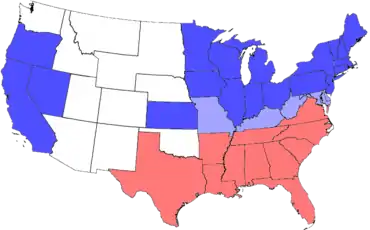

Nationwide, Lincoln took 39.8% of the popular vote, while Douglas won 29.5% of the popular vote, Breckenridge won 18.1%, and Bell won 12.6%.[40] Lincoln carried all but one Northern state, winning a majority of the electoral vote with 180 votes to 72 for Breckinridge, 39 for Bell, and 12 for Douglas. Lincoln won every county in New England and most of the remaining counties in the North, but he won just two of the 996 Southern counties.[41] Lincoln won New York by a margin of 7.4 points; had he lost the state to the Fusion ticket, he would not have won a majority of the electoral vote and a contingent election would have been held in the House of Representatives.[42] The vast majority of Bell's support came from Southern voters, though he did win three percent of the vote in the North.[17] Bell won a plurality of the vote in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia, and finished within five points of Breckinridge or Douglas in North Carolina, Maryland, Missouri, and Louisiana.[43] Bell finished a distant second to Breckinridge in all of the remaining slave states except South Carolina, which did not hold a popular vote for president.

In addition to winning the presidency, the Republican Party made moderate gains in both the U.S. Senate and House in the 1860 elections, though Republicans failed to win a majority of seats in either.[44] However, after southern Democrats withdrew to join the Confederacy, the party gained control of both chambers prior to the start of the 37th Congress. Democrats would have the second-largest number of members in both chambers, although many members identified as unionists rather than Democrats or Republicans.[45][46]

Secession

Following Lincoln's victory, several states in the Deep South seceded and formed the Confederate States of America, but the Upper South initially remained in the Union.[47] Although some supporters of Breckinridge opposed secession and some supporters of Bell supported it, the secession movement was generally led by those who had voted for Breckindrige in the 1860 election, and efforts to avert secession in the South were generally led by those had voted for Bell.[48] The Senate created the Committee of Thirteen, consisting of prominent senators such as Crittenden, Douglas, Democrat Robert Toombs of Georgia, and Republican Benjamin Wade of Ohio.[49] Working closely with Douglas, Crittenden assumed leadership of the Committee of Thirteen even though he was not officially selected as the committee's leader.[50]

Crittenden proposed a package of six constitutional amendments, known as the Crittenden Compromise, that would forbid Congress from abolishing slavery in any state, protect slavery in federal territories south of the 36°30′ parallel, and prohibit it in territories north of that latitude.[51] Crittenden's compromise proved unacceptable to both Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats, and it failed to win approval from the Committee of Thirteen.[52] In another attempt to avert secession, leading politicians in the Lower North and Upper South organized the Peace Conference of 1861.[53] The convention proposed a package of seven constitutional amendments that were largely similar to the Crittenden Compromise.[54] On the last day of the 36th United States Congress, both the Crittenden Compromise and the separate plan proposed at the Peace Convention were rejected in the House and the Senate.[55]

The Civil War began with the Confederate attack of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.[56] After Lincoln called up volunteers in response to the Battle of Fort Sumter, Bell declared his support for the Confederacy. Bell's decision helped convince many other Constitutional Unionists and Southern moderates to support the Confederacy during the Civil War.[57] Other party leaders, including Crittenden and Everett, remained loyal to the Union.

Aftermath

Constitutional Unionists were influential in the Wheeling Convention, which led to the creation of the Union loyalist state of West Virginia, as well as in the declaration of the Kentucky General Assembly for the Union and winning Congressional elections in Kentucky and Maryland in June. Many border state Constitutional Unionists, including John Marshall Harlan, joined unionist parties that sprung up during the war. In Missouri, many of the party joined the new Unconditional Union Party headed by Francis P. Blair, Jr. and remained active in that state's efforts to remain in the Union by overthrowing the elected government of Claiborne Jackson. Everett supported the Union and in 1863 gave a speech at Gettysburg before Lincoln's famous Gettysburg Address.[58]

During Reconstruction, former Whigs and Constitutional Unionists constituted a majority of the scalawags (white members of the Republican Party) in almost every state in the South, joining the Republican Party at a higher rate than pre-war Democrats. Some of these scalawags continued to identify primarily as Whigs as late as the 1890s.[59]

See also

Explanatory notes

- In an alternative scenario envisioned by party leaders, the House would fail to elect a presidential candidate, and the presidency would instead go to whoever the Senate selected as vice president in a separate contingent election.[19]

- The Northern Democratic platform was officially committed to allowing slavery in the territories, but Douglas personally endorsed the doctrine of popular sovereignty in the territories through his Freeport Doctrine.[34]

References

Citations

- Smith, pp. 202–218.

- Holt (2010), pp. 78-89

- McPherson (1988), pp. 126.

- McPherson (1988), p. 129.

- McPherson (1988), pp. 140–141.

- Holt (2010), pp. 91-94, 99, 106-109

- Baggett (2004), pp. 32–33

- Gara (1991), pp. 175–176.

- Holt (2010), pp. 109-110

- Parks (1950), p. 346

- Green (2007), pp. 232–233

- Haynes (2014), pp. 143–144

- Baggett (2004), p. 33

- Green (2007), p. 231

- Wilentz (2006), p. 758

- Egerton (2010), p. 88

- McPherson (1988), pp. 221–223

- Egerton (2010), pp. 89–90

- Sheppard (2014), pp. 515–517

- Egerton (2010), pp. 91–92

- Green (2007), pp. 233–234

- Green (2007), p. 238

- Green (2007), pp. 234–236

- Egerton (2010), pp. 94–95

- Egerton (2010), pp. 91–92, 96

- Egerton (2010), p. 96

- Haley (2002), pp. 372–374

- Egerton (2010), pp. 96–97

- Egerton (2010), pp. 99–100

- Egerton (2010), pp. 100–101

- Egerton (2010), p. 101

- Green (2007), pp. 238–240

- Sheppard (2014), p. 505

- Green (2007), pp. 237–238

- Towers (2011), p. 121

- Green (2007), p. 243

- Green (2007), p. 244

- Sheppard (2014), pp. 511–513

- Egerton (2010), p. 192

- "1860 Presidential General Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections.

- Paludan (1993), p. 5

- Green (2007), p. 250

- Green (2007), p. 251

- White (2009), pp. 350–351.

- "Congress Profiles: 37th Congress (1861–1863)". Washington, D.C.: U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- "Party Division in the Senate, 1789-Present". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Senate. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- White (2009), pp. 361–369.

- Towers (2011), pp. 121–122

- Egerton (2010), p. 288

- Egerton (2010), pp. 294–295

- White (2009), pp. 351–354.

- Egerton (2010), pp. 297–298

- Egerton (2010), pp. 307–308

- Egerton (2010), pp. 311–313

- Egerton (2010), p. 315

- White (2009), pp. 406–407.

- McPherson (1988), pp. 277–278

- "Edward Everett Gives Gettysburg Address - November 19, 1863". massmoments. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- Baggett (2004), pp. 34–37

Works cited

- Baggett, James Alex (2004). The Scalawags: Southern Dissenters in the Civil War and Reconstruction. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807130148.

- Egerton, Doulas R. (2010). Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election that Brought on the Civil War. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781596916197.

- Gara, Larry (1991). The Presidency of Franklin Pierce. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0494-4.

- Green, Don (Summer 2007). "Constitutional Unionists: The Party that Tried to Stop Lincoln and Save the Union". The Historian. 69 (2): 231–253. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2007.00179.x. JSTOR 24453660.

- Haley, James L. (2002). Sam Houston. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3644-8.

- Haynes, Stan M. (2014). The First American Political Conventions: Transforming Presidential Nominations, 1832-1872. McFarland. ISBN 9780786490301.

- Holt, Michael F. (2010). Franklin Pierce. The American Presidents (Kindle ed.). Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 978-0-8050-8719-2.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743902.

- Paludan, Phillip Shaw (1994). The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0671-8.

- Parks, Joseph (1950). John Bell of Tennessee. Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 1470349.

- Sheppard, Si (Winter 2014). ""Union for the Sake of the Union": The Selection of Joseph Lane as Acting President of the United States, 1861". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 115 (4): 502–529. doi:10.5403/oregonhistq.115.4.0502. JSTOR 10.5403/oregonhistq.115.4.0502.

- Smith, Elbert B. (1988). The Presidencies of Zachary Taylor & Millard Fillmore. The American Presidency. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0362-6.

- Towers, Frank (Summer 2011). "Another Look at Inevitability: The Upper South and the Limits of Compromise in the Secession Crisis". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 70 (2): 108–125. JSTOR 42628747.

- White, Ronald C., Jr. (2009). A. Lincoln: A Biography. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6499-1.

- Wilentz, Sean (2006) [2005]. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (Illustrated ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393329216.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Constitutional Union Party". |

.svg.png.webp)