George Walters (VC)

George Walters VC (15 September 1829 – 3 June 1872) was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

George Walters | |

|---|---|

George Walters' VC | |

| Born | 15 September 1829 Newport Pagnell Buckinghamshire |

| Died | 3 June 1872 (aged 42) Marylebone, London |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | Enlisted 1848 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | 49th Regiment of Foot |

| Battles/wars | Crimean War |

| Awards | Victoria Cross |

| Other work | Metropolitan Police officer |

Background

George was born on 15 September 1829 in Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire.[1] His father was James Walters, an Innkeeper in that town. His mother was Jane Green. George was the third child of seven. There are no records of George’s early life and we can only speculate his reasons for joining the Army. 'Going for a soldier' in mid-Victorian England was still not a respectable thing to do but, as industrialism spread, so there was less need for men on the land and unemployment began to be a factor.

49th Regiment

On 1 June 1744, the eight independent companies garrisoning Jamaica were amalgamated into a Regiment on the advice of the Governor, Edward Trelawney who, although he had no previous military experience, was appointed Colonel and the Regiment called Trelawney’s Regiment, as it was the fashion at the time to name Regiments after their Colonel. This Regiment was at first numbered 63rd but after the re-organisation of 1748 it finally became the 49th Regiment of Foot.

In 1782, Regiments were given County titles to assist in recruiting. The 49th Regiment then became known as the 49th (Hertfordshire) Regiment.

The 49th returned from the war in Canada in July 1815 and almost immediately marched from Weymouth where they discarded their battered campaign clothing for new scarlet coats, neat white breeches, black shako and gaiters, and took over the duties of guarding such members of the Royal family who were in residence there. Everything was pipe clayed and polished, the appearance of the men on parade had such an effect on the youthful Princess Charlotte that she begged that the 49th might be ‘her’ Regiment. This was approved, and the title Princess Charlotte of Wales's Regiment was granted later that year.[2]

In 1841, the 49th was sent from India to take part in the First Opium War with China, and it was in action at the capture of Chusan, Canton, Amoy and Shanghai. In consequence of the consistent gallantry displayed by all ranks during the campaign the Regiment was awarded, as a badge, the Dragon super scribed ‘China’. It is the China Dragon that later became the cap badge of the Royal Berkshire Regiment and formed the centrepiece of the Regimental badge of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Royal Regiment.

The British Army alone was an all-volunteer force, whose soldiers enlisted for an initial period of ten years in the Infantry. George Walters joined the 49th in 1848 and was promoted to the rank of Sergeant within six years.

Crimea

On 5 November 1854, the Russians marched out of the besieged city of Sebastopol to throw off the allied British and French forces by mounting a joint attack with their troops from outside the city. Despite outnumbering their enemies five to one the Russians failed to achieve what looked to be a foregone conclusion. This was the third major action of the Crimea War. The battle fought in heavy fog at Inkermann proved to be a testament to the skill and initiative of the individual men and officers of the British Army of the day. Inkermann was an infantry battle of the Crimean War, when the Russians attacked the British forces besieging Sebastopol under cover of fog. In the battle 8,000 British soldiers sustained a hand-to-hand combat with 50,000 Russian troops and it was always referred to as “the soldiers’ battle”.

Very early in the morning, the Russians came out again, this time in much greater strength, and made for the British positions on the Inkermann ridge. The morning was wet and misty, and the visibility was so bad that the British were surprised and had to scramble into action piecemeal. There was little higher control. The regimental officers simply formed their troops as best they could and placed them where they could tackle the great columns looming out of the fog, hoping that the old, tried, formula of desperate courage and superior musketry would prevail against sheer numbers.[3]

The 49th was split from the first. On the left Colonel Dalton led a wing forward, and although he was killed almost immediately, the four companies continued to fight desperately under the inspired command of Major Grant, who time and time again led successful bayonet attacks against the Russians. Further over to the right, the other wing under Lieutenant Bellairs was also heavily engaged throughout the battle, and played a leading role in the fight around the Sandbag Battery. Bellairs, who with his three companies of the 49th including Sergeant Walters, was on the top of Home Ridge. Here the Russians had pushed up the slope to within sixty or eighty yards of the three companies, and were first seen through the mist among the brushwood at that distance. Bellairs at once gave the order to fix bayonets and advance. The men did so without firing a shot till they were within forty yards of the head of the enemy's column, when with a cheer they charged. They were only about one hundred and eighty men, but the Russian column broke before their charge and fled, pursued by the fire of the 49th.

With the repulse of the Russian column near the Sandbag Battery by Brigadier-General Adams with the 41st, the first attack of twenty Russian battalions against the Home Ridge was beaten off. All this had occurred by 7.30 a.m.

General Pauloff was now bringing up his ten thousand Russian soldiers in the centre, and many more guns. Reinforcements were also coming up on the British side, but their numbers were very small compared with their assailants.

Brigadier-General Adams was now near the Sandbag Battery with the 41st, which was joined by Bellairs' companies of the 49th. On Adams' left there was a gap between the 49th companies and the British at the head of the Quarry Ravine. To support Adams, there were two battalions of Guards on the heights in the rear. But he had in front of him an enemy at least five times his strength and both his flanks were open and soon began to be turned. Here there continued a terrible fight in which the British defenders were so broken up into small groups that any detailed description seems impossible. Slowly the gallant seven hundred, whom Brigadier-General Adams commanded, were forced back on the heights to the rear.

During the course of this fierce encounter Brigadier-General Henry Adams CB had his horse killed under him, and as he was also wounded in the leg it seemed certain that he would be either captured or bayoneted by the Russians swarming around him. Very fortunately Sergeant George Walters of the 49th saw that his old commanding officer was in difficulties, and at once charged single-handed into the enemy surrounding the fallen general and drove them off with his bayonet. He then carried his officer back to comparative safety, and eventually he too received the Victoria Cross. Although Adam’s wound was in the ankle only, it became infected and killed him a few days later at Scutari in the notorious Barrack Hospital.[4]

The Grenadier Guards, now coming down on the Sandbag Battery, charged with the bayonet and drove out the Russians. In the fight that ensued here, the remains of Lieutenant Bellairs' companies seem to have been inextricably mixed up. The Sandbag Battery was eventually abandoned for the higher ground behind, but it was again retaken by the Grenadier Guards. After his fight on the spur, on which stood the Sandbag Battery, Lieutenant Bellairs, with the remnants of his three companies, found himself at the head of the Quarry Ravine. Including scattered groups from other battalions, there were about one hundred and fifty men there. Somewhere about 9 a.m. they were preparing to resist the advance of a Russian column moving up the ravine against them when they received repeated orders, from an unidentified field officer, to retire and were compelled to do so, though Bellairs and other officers kept the retreat to a walk. Additions, as they retired, raised the 150 to 200 men. Presently, they found that they were retiring on the French 7th Leger, which was drawn up in good order. This battalion advanced at first, but never charged home and fell back again, the right of it in disorder.

Lieutenant Bellairs was now in rear of its left. The Russian advance here was broken, and the French line restored, by a charge of thirty men under Colonel Daubeny of the 55th directed on the right flank of the enemy column, the head of which was close under the final ascent to the Home Ridge. In repulsing this column, Bellairs appears to have taken his share with the 7th Leger in front. The time was about 9.15 a.m.

Beyond this point we find no further special mention of Lieutenant Bellairs' three companies, but it seems probable that they were again back at the ‘Barrier’ at the head of the Quarry Ravine, where they remained holding their own whilst the principal fight raged on their right.

It was between noon and 1 p.m., when the tide had turned and the Russians were on the point of retreating beaten, when an attempt was decided on to advance with the British left against the Russian batteries on Shell Hill. The attack on the west flank of the batteries was led by the 77th and the battery there was only saved by the guns being carried off in time. At this moment, Captain J. W. Armstrong of the 49th, then on the staff, galloped up and urged forward all the troops he could find to support the 17th. Amongst them was a complete company of the 49th, under Lieutenant Astley, and this joined in the advance against the battery and the pursuit. The Russians now retreated unpursued, for the French, who had played but a poor part in this great day, declined to follow, and they were the only troops which were in a condition to do anything.

The losses of the 49th Regiment of Foot in the Battle of Inkermann were:- Killed: Major Dalton, Lieutenant and Adjutant A. S. Armstrong, 2 Sergeants, 1 Drummer, and 37 Rank and File. Wounded: Lieutenant Dewar (slightly), 9 Sergeants, 1 Drummer, 98 Rank and File.

In addition to these, it must be remembered the death of Brigadier-General Henry W. Adams, C.B. The whole battle was fought under conditions of such indescribable confusion that it is hardly possible to compile a detailed account of the part played by the 49th. Some indication is given by the fact that in seven hours fighting it lost over a hundred and fifty men, about a quarter of its effective strength.

In total the British lost about 2,400 troops, the French about 1,000 and the Russians an estimated 11,000. After Inkermann, the 49th returned to the duties of the siege. The Digest of Service is silent on the subject of privation and disease but everyone knows what the miseries of the army were in that first winter on the bleak heights of the Chersonese, with insufficient shelter and food, in great cold, and in such visitations as that of the great storm which devastated the crowded harbour of Balaklava on 14 November 1854. The only allusion in the Digest is a statement which shows that in the Crimean War the 49th Regiment of Foot lost 191 officers and men by disease, besides 178 invalided.[5]

The 49th saw the Crimea War out to the end. It survived the first terrible winter on the plateau, not without heavy losses, and fought on in the trenches until eventually Sebastopol fell and the war ended. Even then it did not leave the theatre immediately, but spent a second winter there, although fortunately under conditions of luxury compared to those of the earlier one.[6]

A Royal Warrant issued on 29 January 1856 founded the Victoria Cross. The warrant announced the creation of a single decoration available to the Army and Royal Navy, which was intended to reward 'individual instances of merit and valour' and which 'we are desirous should be highly prized and eagerly sought after'. The warrant laid down fifteen 'rules and ordinances'. Essentially, the award was intended for extreme bravery in the presence of the enemy. It was also decided that the cross should be made from metal of little intrinsic value. It was intended that it should be bronze and cast from metal melted down from two cannon supposedly captured from the Russians at Sebastopol in the Crimean War.

On 8 September 1856 George married Mary Ann Norman at the Parish Church in Newport Pagnell. He was still a Sergeant in the 49th and gave his address as Newport Pagnell. His father James, the Innkeeper, was in attendance.[7]

Later life

Shortly after the wedding, on 5 January 1857 George left the Army and joined the Metropolitan Police as Constable 444 of R Division. It was more than a year after the Royal Warrant was signed that the first awards of the VC were published in the London Gazette on 24 February 1857. The formal, rather stilted language of citations hardly ever conveys the violence, danger and sheer excitement of the actions, which win awards. George Walter's deed was gazetted as follows:[8]

Sergeant George Walters highly distinguished himself at the Battle of Inkermann, in having rescued Brigadier-General Adams, C.B., when surrounded by Russians, one of whom he bayoneted

On 21 June 1857, Mary Ann Walters gave birth to a son named James Isaac Walters. The Birth Certificate states that George Walters was now a Police Constable and they lived at 10 Lucas Street in Deptford, Kent.

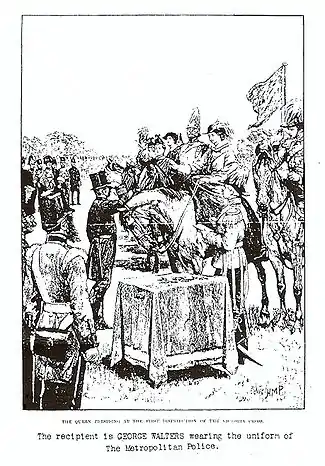

The Queen made it plain to Lord Panmure that she herself wished to bestow her new award on as many of the recipients as possible. The 26 June 1857 was chosen by the Queen as a suitable day, and that a grand parade should be laid on in Hyde Park and that she would 'herself' attend on horseback. The final list of recipients was not published in the London Gazette until 22 June, and Hancock's had to work around the clock to engrave the names of the recipients on the Crosses. Those destined to receive the award had somehow to be found and rushed up to London, together with detachments of the units in which they had served. Queen Victoria caused some consternation by electing to stay on horseback throughout the ceremony of awarding the sixty-two recipients with the Cross. An extract in Queen Victoria’s Day Diary is as follows:

“It was a beautiful sight, & everything admirably arranged. All the Royal Family, including little Leopold, followed in carriages. The road all along was kept clear, & there was no pushing or squeezing. Constant cheering & noises of every kind, but the horses went beautifully. George & the Staff met just within the Quadrangle Entrance of the Palace, & preceded us. The sight in Hyde Park was very fine, the tribunes & stands, full of spectators, the Royal one being in the centre. After riding down the Line the ceremony of giving medals, began. There were 47 in number, with blue ribbons for the Navy, & red, for the Army. I remained on horseback, fastening the medals, or crosses, on recipient [sic]. Some were in plain clothes, - one a Gate Keeper & one a Policeman*. Lord Panmure stood to my left, handing me the medals, & to my right, Sir C. Wood, whilst the naval men were being decorated, & Sir G. Weatherall; for the soldiers, each reading the names out, as the men came up”.

The Policeman was of course George Walters and George was the 51st person to receive the Victoria Cross. A total of 12 Victoria Cross medals were awarded to those who fought in the Battle of Inkermann.

The Times, on the following day published the following article:

“A new epoch in our military history was yesterday inaugurated in Hyde Park. The old and much abused campaign medal may now be looked upon as a reward, but it will cease to be sought after as a distinction, for a new order is instituted - an order for merit and valour, open, without regard to rank or title, to all whose conduct in the field has rendered them prominent for courage even in the British army. A path is left open to this ambition of the humblest soldier - a road is open to honour which thousands have toiled, and pined, and died in the endeavour to attain, and private soldiers may now look forward to wearing a real distinction which kings might be proud to have earned the right to bear.... The display of yesterday in point of numbers was a great metropolitan gathering - it was a concourse such as only London could send forth....

The persons who composed the fashionable portion of the visitors, if we may so term those who were admitted to the reserved seats, were very punctual in their attendance, and every part of the great expanse of platform was well covered soon after 9 o ·clock. The heat throughout the entire proceedings was intense; the ladies seemed to suffer much from it, and even strong, hearty gentlemen were not too fastidious to extemporize rude fans from coat-tails, handkerchiefs, and morning journals or any suitable material at hand. Not a breath of air seemed stirring, and the standard which marked the Queen's position drooped heavily down, as if it too suffered from the sun and was incapable of fluttering or active motion. Everybody simmered into a state of aggravation, and everybody gasped and said how hot it was in a tone of private communication, as if the temperature was a State secret which must not be bruited abroad. In less tropical nooks, beneath the trees, costermongers drove a brave trade in the retail of liquids from portly-looking barrels which we fancy must have contained something better than water, as policemen formed the staple of their customers....

A few minutes before 10 o'clock the officers and men who were to receive the "high honour" of the Victoria Cross marched in single file across the park to the Queen's position. Their appearance created a deep sensation, and well it might, for upon a more distinguished band of soldiers the public have never yet gazed. One was a policeman, and wore his plain uniform as a constable of the R Division, No 444. This was George Walters, late Sergeant of the 49th Regiment who highly distinguished himself at lnkermann in rescuing General Adams when surrounded by Russians. Surely for such a man a better post may be found than that of a constable at 18s a week. Another in the dress of a park keeper was formerly a corporal in the 23rd, who volunteered on September the 8th to go out, under a murderous fire, to the front, after the attack on the Redan, and carry Lieutenant Dyneley - mortally wounded....

Queen Victoria presenting VC in Hyde Park on 26 June 1857As they stood in a row, waiting the arrival of Her Majesty, one could not help feeling an emotion of sorrow that they were so few, and that the majority of the men who would have done honour even to the Victoria Cross lie in their shallow graves on the bleak cliffs of the Crimea....

Where were the men who climbed the heights of Alma, who hurried forward over the plain of Balaklava to almost certain death, who, wearied and outnumbered yet held their ground on that dismal morning when the valley of Inkermann seethed with flames and smoke like some vast hellish cauldron? Where are the troops who during that fearful winter toiled through the snow night after night, with just sufficient strength to drag their sick and wasted forms down to the trenches which became their graves? Let not these men be forgotten at such a time, nor while we pay all honour to the few survivors of that gallant little army omit a tribute to the brave who have passed away for ever....”

Another leading article that day commented on the events. It found much to praise but complained about the lack of seats and cover for the public. It concluded with some damning criticism.

“We have forgotten the Medal itself, or the Cross, rather, for such it is. Would we could forget it! Never did we see such a dull, heavy, tasteless affair. Much do we suspect that if it was on sale in any town in England at a penny a-piece, hardly a dozen would be sold in a twelve-month. There is a cross, and a lion, and a scroll or two worked up into the most shapeless mass that the size admits of. Valour must, and doubtless will, be still its own reward in this country, for the Victoria Cross is the shabbiest of all prizes.”

Regardless, the Queen managed to pin on the whole batch in just ten minutes, which does not suggest lengthy conversation, but the whole parade went off extremely well to the rapturous applause of more than 4,000 troops and 12,000 spectators.

George resigned from the Metropolitan Police on 26 October 1857 under Certificate No. 4 (1 = Excellent, 2 = Very Good. 3 = Good, and 4 = Open, i.e. no comment).[11] Maybe he left the Mets after such a short period in order to join the Regents Park Police and hence the fairly innocuous reference. No further record exists of George Walters until the 1871 English Census. On 2 April 1871, George is shown as a visitor at North End, Newport Pagnell of the Maply family and his occupation is given as Park Keeper. Conversely, Mary Ann Walters is shown living at Lodge House, Park Crescent, Marylebone (the gatehouse to Regents Park) with sons James Isaac, aged 13, George, aged 12, and Ephraim Robert, aged 2. Mary gave her occupation as Park Constable’s wife. They are the only census records that record George Walters.[12]

On 3 June 1872, George died at West Lodge, Park Crescent, Marylebone. In attendance was Dr. William Marsh of Harley Street Lodge. George had been suffering with Phthisis for three years, which literally means a wasting disease but almost invariably will mean pulmonary tuberculosis or any debilitating lung or throat affections, a severe cough, asthma.[7] He was buried on 9 June 1872 in the City of Westminster Cemetery in Finchley.

Burial

Research was carried out in 1997 to track down the unidentified graves of VC winners. It seems that George Walters died in poverty and was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave. His grave was found using cemetery records. In January 1998 a new gravestone was dedicated at a short but moving graveside ceremony, which was attended by members of the Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Regiment and Regimental Association including two pensioners from the Royal Hospital Chelsea. Inspector Paul Rason, Chairman of the Metropolitan Police Museum, was also present to pay tribute to one of his own.[13]

The new gravestone is engraved with the China Dragon of the Royal Berkshire Regiment and the Victoria Cross, and has the inscription ‘AT THIS PLACE LIE THE REMAINS OF SGT GEORGE WALTERS VC. 49TH REGIMENT OF FOOT. BORN 15 SEPT 1829. DIED 3 JUNE 1872. ERECTED BY HIS REGIMENT IN 1997 IN MEMORY OF A COURAGEOUS SOLDIER’

He lies in Plot 55 of Zone E10 at the renamed East Finchley Cemetery, London N2 0RZ.

Later a Commemorative Plaque was unveiled and a Memorial Panel displayed at the British Legion Newport Pagnell for ‘A GALLANT SON OF NEWPORT PAGNELL’.

The medal

_and_the_Turkish_Crimea_Medal.jpg.webp)

George Walters' Victoria Cross is displayed at The Rifles (Berkshire and Wiltshire) Museum (Salisbury, Wiltshire, England) together with his Crimea Medal with three Clasps (Alma, Inkermann & Sebestopol) and the Turkish Crimea Medal. They are not always on public display.

References

- Parish Records of the Independent Chapel, Newport Pagnell

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Battle of Inkerman 5 November 1854: The 20th Regiment of Foot by David Rowlands (Military Artist) Owner: Private Collection

- "No. 21971". The London Gazette. 24 February 1857. p. 660.

- The Rifles (Berkshire & Wiltshire) Museum. The Royal Berkshire Regiment's History. pp. 150–151

- Frederick Myatt.The Royal Berkshire Regiment (the 49th/66th Regiment of Foot)H. Hamilton, 1968

- General Register Office

- Supplement to the London Gazette, dated 24 February 1857, page 660. National Archives. Catalogue ref: WO/98/3.

- Queen Victoria's Day Diary, Buckingham Palace, dated 26 June 1857 page 113. PRO, WO32/7304 for the whole episode

- The Times, 27 June 1857

- Metropolitan Police Museum Historical Records.

- 1871 England Census Records.

- Ministry of Defence FOCUS magazine January 1998 page 12

External links

- Location of grave and VC medal (N. London)

- Location of George Walters Victoria Cross (The Wardrobe. The Rifles (Berkshire and Wiltshire) Museum - the story of the Infantry of Berkshire and Wiltshire)