German cruiser Prinz Eugen

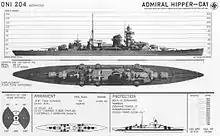

Prinz Eugen (German pronunciation: [ˈpʁɪnts ɔʏˈɡeːn]) was an Admiral Hipper-class heavy cruiser, the third of a class of five vessels. She served with Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine during World War II. The ship was laid down in April 1936, launched in August 1938, and entered service after the outbreak of war, in August 1940. She was named after Prince Eugene of Savoy, an 18th-century Austrian general. She was armed with a main battery of eight 20.3 cm (8.0 in) guns and, although nominally under the 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) limit set by the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, actually displaced over 16,000 long tons (16,000 t).

As USS Prinz Eugen, before the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Prinz Eugen |

| Namesake: | Prince Eugene of Savoy |

| Builder: | Germaniawerft |

| Laid down: | 23 April 1936 |

| Launched: | 22 August 1938 |

| Commissioned: | 1 August 1940 |

| Decommissioned: | 7 May 1945 |

| Fate: | Surrendered 8 May 1945, transferred to US Navy |

| History | |

| Name: | USS Prinz Eugen |

| Commissioned: | 5 January 1946 |

| Decommissioned: | 29 August 1946 |

| Fate: | Towed to Kwajalein Atoll after Operation Crossroads nuclear weapons tests; capsized 22 December 1946 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Admiral Hipper-class cruiser |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 212.5 m (697 ft 2 in) overall |

| Beam: | 21.7 m (71 ft 2 in) |

| Draft: | Full load: 7.2 m (24 ft) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 3 Arado Ar 196 |

| Aviation facilities: | 1 catapult |

| Notes: | Figures are for the ship as built |

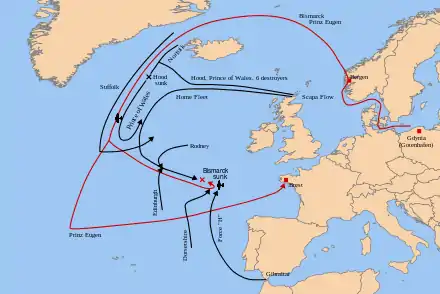

Prinz Eugen saw action during Operation Rheinübung, an attempted breakout into the Atlantic Ocean with the battleship Bismarck in May 1941. The two ships destroyed the British battlecruiser Hood and moderately damaged the battleship Prince of Wales in the Battle of the Denmark Strait. Prinz Eugen was detached from Bismarck during the operation to raid Allied merchant shipping, but this was cut short due to engine troubles. After putting into occupied France and undergoing repairs, the ship participated in Operation Cerberus, a daring daylight dash through the English Channel back to Germany. In February 1942, Prinz Eugen was deployed to Norway, although her time stationed there was curtailed when she was torpedoed by the British submarine Trident days after arriving in Norwegian waters. The torpedo severely damaged the ship's stern, which necessitated repairs in Germany.

Upon returning to active service, the ship spent several months training officer cadets in the Baltic before serving as artillery support for the retreating German Army on the Eastern Front. After the German collapse in May 1945, she was surrendered to the British Royal Navy before being transferred to the US Navy as a war prize. After examining the ship in the United States, the US Navy assigned the cruiser to the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll. Having survived the atomic blasts, Prinz Eugen was towed to Kwajalein Atoll, where she ultimately capsized and sank in December 1946. The wreck remains partially visible above the water approximately two miles northwest of Bucholz Army Airfield, on the edge of Enubuj. One of her screw propellers was salvaged and is on display at the Laboe Naval Memorial in Germany.

Design

The Admiral Hipper class of heavy cruisers was ordered in the context of German naval rearmament after the Nazi Party came to power in 1933 and repudiated the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles. In 1935, Germany signed the Anglo–German Naval Agreement with Great Britain, which provided a legal basis for German naval rearmament; the treaty specified that Germany would be able to build five 10,000-long-ton (10,000 t) "treaty cruisers".[1] The Admiral Hippers were nominally within the 10,000-ton limit, though they significantly exceeded the figure.[2]

Prinz Eugen was 207.7 meters (681 ft) long overall, and had a beam of 21.7 m (71 ft) and a maximum draft of 7.2 m (24 ft). After launching, her straight bow was replaced with a clipper bow, increasing the length overall to 212.5 meters (697 ft). The new bow kept her foredeck much drier in heavy weather.[3] The ship had a design displacement of 16,970 t (16,700 long tons; 18,710 short tons) and a full-load displacement of 18,750 long tons (19,050 t). Prinz Eugen was powered by three sets of geared steam turbines, which were supplied with steam by twelve ultra-high pressure oil-fired boilers. The ship's top speed was 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph), at 135,619 shaft horsepower (101.131 MW).[4] As designed, her standard complement consisted of 42 officers and 1,340 enlisted men.[5]

The ship's primary armament was eight 20.3 cm (8.0 in) SK L/60 guns mounted in four twin turrets, placed in superfiring pairs forward and aft.[lower-alpha 1] Her anti-aircraft battery consisted of twelve 10.5 cm (4.1 in) L/65 guns, twelve 3.7 cm (1.5 in) guns, and eight 2 cm (0.79 in) guns. The ship also carried a pair of triple 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo launchers abreast of the rear superstructure. For aerial reconnaissance, she was equipped with three Arado Ar 196 seaplanes and one catapult.[5] Prinz Eugen's armored belt was 70 to 80 mm (2.8 to 3.1 in) thick; her upper deck was 12 to 30 mm (0.47 to 1.18 in) thick and her main armored deck was 20 to 50 mm (0.79 to 1.97 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 105 mm (4.1 in) thick faces and 70 mm thick sides.[4]

Service history

Prinz Eugen was ordered by the Kriegsmarine from the Germaniawerft shipyard in Kiel.[4] Her keel was laid down on 23 April 1936,[6] under construction number 564 and the contract name Kreuzer J.[4] She was originally to be named after Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, the Austrian victor of the Battle of Lissa, though considerations over the possible insult to Italy, defeated by Tegetthoff at Lissa, led the Kriegsmarine to adopt Prinz Eugen as the ship's namesake.[7] She was launched on 22 August 1938,[8] in a ceremony attended by the Governor (Reichsstatthalter) of the Ostmark, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, who made the christening speech. Also present at the launch were Adolf Hitler, the Regent of Hungary, Admiral Miklós Horthy (who had commanded the battleship SMS Prinz Eugen from 24 November 1917 to 1 March 1918), and his wife Magdolna Purgly, who performed the christening.[9] As built, the ship had a straight stem, though after her launch this was replaced with a clipper bow. A raked funnel cap was also installed.[10]

Commissioning was delayed slightly due to light damage sustained during a Royal Air Force attack on Kiel on the night of 1 July 1940. Prinz Eugen suffered two relatively light hits in the attack,[9] but she was not seriously damaged and was commissioned into service on 1 August.[8] The cruiser spent the remainder of 1940 conducting sea trials in the Baltic Sea.[6] In early 1941, the ship's artillery crews conducted gunnery training. A short period in dry dock for final modifications and improvements followed.[11] In April, the ship joined the newly commissioned battleship Bismarck for maneuvers in the Baltic. The two ships had been selected for Operation Rheinübung, a breakout into the Atlantic to raid Allied commerce.[12]

On 23 April, while passing through the Fehmarn Belt en route to Kiel,[13] Prinz Eugen detonated a magnetic mine dropped by British aircraft. The mine damaged the fuel tank, propeller shaft couplings,[12] and fire control equipment.[13] The planned sortie with Bismarck was delayed while repairs were carried out.[12] Admirals Erich Raeder and Günther Lütjens discussed the possibility of delaying the operation further, in the hopes that repairs to the battleship Scharnhorst would be completed or Bismarck's sistership Tirpitz would complete trials in time for the ships to join Prinz Eugen and Bismarck. Raeder and Lütjens decided that it would be most beneficial to resume surface actions in the Atlantic as soon as possible, however, and that the two ships should sortie without reinforcement.[14]

Operation Rheinübung

By 11 May 1941, repairs to Prinz Eugen had been completed. Under the command of Kapitän zur See (KzS—Captain at Sea) Helmuth Brinkmann, the ship steamed to Gotenhafen, where the crew readied her for her Atlantic sortie. On 18 May, Prinz Eugen rendezvoused with Bismarck off Cape Arkona.[12] The two ships were escorted by three destroyers—Hans Lody, Z16 Friedrich Eckoldt, and Z23—and a flotilla of minesweepers.[15] The Luftwaffe provided air cover during the voyage out of German waters.[16] At around 13:00 on 20 May, the German flotilla encountered the Swedish cruiser HSwMS Gotland; the cruiser shadowed the Germans for two hours in the Kattegat.[17] Gotland transmitted a report to naval headquarters, stating: "Two large ships, three destroyers, five escort vessels, and 10–12 aircraft passed Marstrand, course 205°/20'."[16] The Oberkommando der Marine (OKM—Naval High Command) was not concerned about the security risk posed by Gotland, though Lütjens believed operational security had been lost.[17] The report eventually made its way to Captain Henry Denham, the British naval attaché to Sweden, who transmitted the information to the Admiralty.[18]

The code-breakers at Bletchley Park confirmed that an Atlantic raid was imminent, as they had decrypted reports that Bismarck and Prinz Eugen had taken on prize crews and requested additional navigational charts from headquarters. A pair of Supermarine Spitfires were ordered to search the Norwegian coast for the German flotilla.[19] On the evening of 20 May, Prinz Eugen and the rest of the flotilla reached the Norwegian coast; the minesweepers were detached and the two raiders and their destroyer escorts continued north. The following morning, radio-intercept officers on board Prinz Eugen picked up a signal ordering British reconnaissance aircraft to search for two battleships and three destroyers northbound off the Norwegian coast.[20] At 7:00 on the 21st, the Germans spotted four unidentified aircraft that quickly departed. Shortly after 12:00, the flotilla reached Bergen and anchored at Grimstadfjord. While there, the ships' crews painted over the Baltic camouflage with the standard "outboard gray" worn by German warships operating in the Atlantic.[21]

While in Bergen, Prinz Eugen took on 764 t (752 long tons; 842 short tons) of fuel; Bismarck inexplicably failed to similarly refuel.[22] At 19:30 on 21 May, Prinz Eugen, Bismarck, and the three escorting destroyers left port.[23] By midnight, the force was in the open sea and headed toward the Arctic Ocean. At this time, Admiral Raeder finally informed Hitler of the operation, who reluctantly allowed it to continue as planned. The three escorting destroyers were detached at 04:14 on 22 May, while the force steamed off Trondheim. At around 12:00, Lütjens ordered his two ships to turn toward the Denmark Strait to attempt the breakout into the open waters of the Atlantic.[24]

By 04:00 on 23 May, Lütjens ordered Prinz Eugen and Bismarck to increase speed to 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) to make the dash through the Denmark Strait.[25] Upon entering the Strait, both ships activated their FuMO radar detection equipment sets.[26] Bismarck led Prinz Eugen by about 700 m (2,300 ft); mist reduced visibility to 3,000 to 4,000 m (9,800 to 13,100 ft). The Germans encountered some ice at around 10:00, which necessitated a reduction in speed to 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph). Two hours later, the pair had reached a point north of Iceland. The ships were forced to zigzag to avoid ice floes. At 19:22, hydrophone and radar operators aboard the German warships detected the cruiser HMS Suffolk at a range of approximately 12,500 m (41,000 ft).[25] Prinz Eugen's radio-intercept team decrypted the radio signals being sent by Suffolk and learned that their location had indeed been reported.[27]

Admiral Lütjens gave permission for Prinz Eugen to engage Suffolk, though the captain of the German cruiser could not clearly make out his target and so held fire.[28] Suffolk quickly retreated to a safe distance and shadowed the German ships. At 20:30, the heavy cruiser HMS Norfolk joined Suffolk, but approached the German raiders too closely. Lütjens ordered his ships to engage the British cruiser; Bismarck fired five salvoes, three of which straddled Norfolk and rained shell splinters on her decks. The cruiser laid a smoke screen and fled into a fog bank, ending the brief engagement. The concussion from the 38 cm guns disabled Bismarck's FuMo 23 radar set; this prompted Lütjens to order Prinz Eugen to take station ahead so she could use her functioning radar to scout for the formation.[29]

The British cruisers tracked Prinz Eugen and Bismarck through the night, continually relaying the location and bearing of the German ships. The harsh weather broke on the morning of 24 May, revealing a clear sky. At 05:07 that morning, hydrophone operators aboard Prinz Eugen detected a pair of unidentified vessels approaching the German formation at a range of 20 nmi (37 km; 23 mi), reporting "Noise of two fast-moving turbine ships at 280° relative bearing!".[30] At 05:45, lookouts on the German ships spotted smoke on the horizon; these turned out to be from Hood and Prince of Wales, under the command of Vice Admiral Lancelot Holland. Lütjens ordered his ships' crews to battle stations. By 05:52, the range had fallen to 26,000 m (85,000 ft) and Hood opened fire, followed by Prince of Wales a minute later.[31] Hood engaged Prinz Eugen, which the British thought to be Bismarck, while Prince of Wales fired on Bismarck.[lower-alpha 2]

The British ships approached the Germans head on, which permitted them to use only their forward guns, while Bismarck and Prinz Eugen could fire full broadsides. Several minutes after opening fire, Holland ordered a 20° turn to port, which would allow his ships to engage with their rear gun turrets. Both German ships concentrated their fire on Hood. About a minute after opening fire, Prinz Eugen scored a hit with a high-explosive 20.3 cm (8.0 in) shell, detonating unrotated projectile ammunition and starting a large fire on Hood, which was quickly extinguished.[32] Holland then ordered a second 20° turn to port, to bring his ships on a parallel course with Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. By this time, Bismarck had found the range to Hood, so Lütjens ordered Prinz Eugen to shift fire and target Prince of Wales to keep both of his opponents under fire. Within a few minutes, Prinz Eugen scored a pair of hits on the battleship and reported that a small fire had been started.[33]

Lütjens then ordered Prinz Eugen to drop behind Bismarck, so she could continue to monitor the location of Norfolk and Suffolk, which were still some 10 to 12 nmi (19 to 22 km; 12 to 14 mi) to the east. At 06:00, Hood was completing her second turn to port when Bismarck's fifth salvo hit. Two of the shells landed short, striking the water close to the ship, but at least one of the 38 cm armor-piercing shells struck Hood and penetrated her thin upper belt armor. The shell reached Hood's rear ammunition magazine and detonated 112 t (110 long tons; 123 short tons) of cordite propellant.[34] The massive explosion broke the back of the ship between the main mast and the rear funnel; the forward section continued to move forward briefly before the in-rushing water caused the bow to rise into the air at a steep angle. The stern similarly rose upward as water rushed into the ripped-open compartments.[35] After only eight minutes of firing, Hood had disappeared, taking all but three of her crew of 1,419 men with her.[36]

After a few more minutes, during which Prince of Wales scored three hits on Bismarck, the damaged British battleship withdrew. The Germans ceased fire as the range widened, though Captain Ernst Lindemann, Bismarck's commander, strongly advocated chasing Prince of Wales and destroying her.[37] Lütjens firmly rejected the request, and instead ordered Bismarck and Prinz Eugen to head for the open waters of the North Atlantic.[38] After the end of the engagement, Lütjens reported that a "Battlecruiser, probably Hood, sunk. Another battleship, King George V or Renown, turned away damaged. Two heavy cruisers maintain contact."[39] At 08:01, he transmitted a damage report and his intentions to OKM, which were to detach Prinz Eugen for commerce raiding and to make for St. Nazaire for repairs.[40] Shortly after 10:00, Lütjens ordered Prinz Eugen to fall behind Bismarck to discern the severity of the oil leakage from the bow hit. After confirming "broad streams of oil on both sides of [Bismarck's] wake",[41] Prinz Eugen returned to the forward position.[41]

With the weather worsening, Lütjens attempted to detach Prinz Eugen at 16:40. The squall was not heavy enough to cover her withdrawal from Wake-Walker's cruisers, which continued to maintain radar contact. Prinz Eugen was therefore recalled temporarily.[42] The cruiser was successfully detached at 18:14. Bismarck turned around to face Wake-Walker's formation, forcing Suffolk to turn away at high speed. Prince of Wales fired twelve salvos at Bismarck, which responded with nine salvos, none of which hit. The action diverted British attention and permitted Prinz Eugen to slip away.[43]

On 26 May, Prinz Eugen rendezvoused with the supply ship Spichern to refill her nearly empty fuel tanks.[44] She had by then only 160 tons fuel left, enough for a day.[45] Afterwards the ship continued further south on a mission against shipping lines.[46] Before any merchant ship was found, defects in her engines showed and on 27 May, the day Bismarck was sunk, she was ordered to give up her mission and make for a port in occupied France.[47] On 28 May Prinz Eugen refuelled from the tanker Esso Hamburg. The same day more engine problems showed up, including trouble with the port engine turbine, the cooling of the middle engine and problems with the starboard screw, reducing her maximum speed to 28 knots.[48] The screw problems could only be checked and repaired in a dock and thus Brest, with its large docks and repair facilities, was chosen as destination. Despite the many British warships and several convoys in the area, at least 104 units were identified on the 29th by the ship's radio crew, Prinz Eugen reached the Bay of Biscay undiscovered, and on 1 June the ship was joined by German destroyers and aircraft off the coast of France south of Brest;[49] and escorted to Brest, which she reached late on 1 June where she immediately entered dock.[44][50]

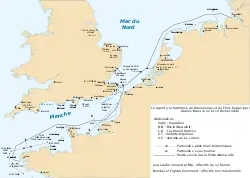

Operation Cerberus and Norwegian operations

Brest is not far from bases in southern England and during their stay in Brest Prinz Eugen and the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were repeatedly attacked by Allied bombers.[49] The Royal Air Force jokingly referred to the three ships as the Brest Bomb Target Flotilla, and between 1 August and 31 December 1941 it dropped some 1200 tons of bombs on the port.[51] On the night of 1 July 1941,[44] Prinz Eugen was struck by an armor-piercing bomb that destroyed the control center deep down under the bridge. The attack killed 60 men and wounded more than 40 others.[52][49][53] The loss of the control center also made the main guns useless and repairs lasted until the end of 1941.[51]

The continuous air attacks led the German command to decide Prinz Eugen, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau would have to move to safer bases as soon as they were repaired and ready. Meanwhile, the Bismarck operation had demonstrated the risks of operating in the Atlantic without air cover. In addition, Hitler saw the Norwegian theater as the "zone of destiny", so he ordered the three ships' return to Germany in early 1942 so they could be deployed there.[54][55] The intention was to use the ships to interdict Allied convoys to the Soviet Union, as well as to strengthen the defenses of Norway.[54] Hitler insisted they would make the voyage via the English Channel, despite Raeder's protests that it was too risky.[56] Vice Admiral Otto Ciliax was given command of the operation. In early February, minesweepers swept a route through the Channel, though the British failed to detect the activity.[54]

At 23:00 on 11 February, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, and Prinz Eugen left Brest. They entered the Channel an hour later; the three ships sped at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph), hugging the French coast along the voyage. By 06:30, they had passed Cherbourg, at which point they were joined by a flotilla of torpedo boats.[54] The torpedo boats were led by Kapitän zur See Erich Bey, aboard the destroyer Z29. General der Jagdflieger (General of Fighter Force) Adolf Galland directed Luftwaffe fighter and bomber forces (Operation Donnerkeil) during Cerberus.[57] The fighters flew at masthead-height to avoid detection by the British radar network. Liaison officers were present on all three ships. German aircraft arrived later to jam British radar with chaff.[54] By 13:00, the ships had cleared the Strait of Dover but, half an hour later, a flight of six Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, with Spitfire escort, attacked the Germans. The British failed to penetrate the Luftwaffe fighter shield, and all six Swordfish were destroyed.[58][59]

Off Dover, Prinz Eugen came under fire from British coastal artillery batteries, though they scored no hits. Several Motor Torpedo Boats then attacked the ship, but Prinz Eugen's destroyer escorts drove the vessels off before they could launch their torpedoes. At 16:43, Prinz Eugen encountered five British destroyers: Campbell, Vivacious, Mackay, Whitshed, and Worcester. She fired her main battery at them and scored several hits on Worcester, but she was forced to maneuver erratically to avoid their torpedoes.[60] Nevertheless, Prinz Eugen arrived in Brunsbüttel on the morning of 13 February, completely undamaged[56] but suffering the only casualty in all three big ships, killed by aircraft gunfire.[61]

On 21 February 1942, Prinz Eugen, the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer, and the destroyers Richard Beitzen, Paul Jakobi, Z25, Hermann Schoemann, and Friedrich Ihn steamed to Norway.[62] After stopping briefly in Grimstadfjord, the ships proceeded on to Trondheim. Two days later, while patrolling off the Trondheimsfjord, the British submarine Trident torpedoed Prinz Eugen.[60] The torpedo struck the ship in the stern, killing fifty men, causing serious damage, and rendering the ship unmaneuverable. However, on her own power she managed to reach Trondheim and from there was towed to Lofjord, where, over the next few months, emergency repairs were effected. Her entire stern was cut away and plated over and two jury-rigged rudders, operated manually by capstans, were installed.[56][63]

On 16 May, Prinz Eugen made the return voyage to Germany under her own power. While en route to Kiel, the ship was attacked by a British force of 19 Bristol Blenheim bombers and 27 Bristol Beaufort torpedo bombers commanded by Wing Commander Mervyn Williams, though the aircraft failed to hit the ship.[60] Prinz Eugen was out of service for repairs until October; she conducted sea trials beginning on 27 October.[64] Hans-Erich Voss, who later became Hitler's Naval Liaison Officer, was given command of the ship when she returned to service.[65] In reference to her originally planned name, the ship's bell from the Austrian battleship Tegetthoff was presented on 22 November by the Italian Contrammiraglio (Rear Admiral) de Angeles.[66] Over the course of November and December, the ship was occupied with lengthy trials in the Baltic. In early January 1943, the Kriegsmarine ordered the ship to return to Norway to reinforce the warships stationed there. Twice in January Prinz Eugen attempted to steam to Norway with Scharnhorst, but both attempts were broken off after British surveillance aircraft spotted the two ships. After it became apparent that it would be impossible to move the ship to Norway, Prinz Eugen was assigned to the Fleet Training Squadron. For nine months, she cruised the Baltic training cadets.[64]

Service in the Baltic

As the Soviet Army pushed the Wehrmacht back on the Eastern Front, it became necessary to reactivate Prinz Eugen as a gunnery support vessel; on 1 October 1943, the ship was reassigned to combat duty.[64] In June 1944, Prinz Eugen, the heavy cruiser Lützow, and the 6th Destroyer Flotilla formed the Second Task Force, later renamed Task Force Thiele after its commander, Vizeadmiral August Thiele. Prinz Eugen was at this time under the command of KzS Hans-Jürgen Reinicke; throughout June she steamed in the eastern Baltic, northwest of the island of Utö as a show of force during the German withdrawal from Finland. On 19–20 August, the ship steamed into the Gulf of Riga and bombarded Tukums.[67][68] Four destroyers and two torpedo boats supported the action, along with Prinz Eugen's Ar 196 floatplanes; the cruiser fired a total of 265 shells from her main battery.[64][68] Prinz Eugen's bombardment was instrumental in the successful repulse of the Soviet attack.[69]

In early September, Prinz Eugen supported a failed attempt to seize the fortress island of Hogland. The ship then returned to Gotenhafen, before escorting a convoy of ships evacuating German soldiers from Finland.[64] The convoy, consisting of six freighters, sailed on 15 September from the Gulf of Bothnia, with the entire Second Task Force escorting it. Swedish aircraft and destroyers shadowed the convoy, but did not intervene. The following month, Prinz Eugen returned to gunfire support duties. On 11 and 12 October, she fired in support of German troops in Memel.[67] Over the first two days, the ship fired some 700 rounds of ammunition from her main battery. She returned on the 14th and 15th, after having restocked her main battery ammunition, to fire another 370 rounds.[64]

While on the return voyage to Gotenhafen on 15 October, Prinz Eugen inadvertently rammed the light cruiser Leipzig amidships north of Hela.[64] The cause of the collision was heavy fog.[70] The light cruiser was nearly cut in half,[64] and the two ships remained wedged together for fourteen hours.[67] Prinz Eugen was taken to Gotenhafen, where repairs were effected within a month.[64] Sea trials commenced on 14 November.[68] On 20–21 November, the ship supported German troops on the Sworbe Peninsula by firing around 500 rounds of main battery ammunition. Four torpedo boats—T13, T16, T19, and T21—joined the operation.[68] Prinz Eugen then returned to Gotenhafen to resupply and have her worn-out gun barrels re-bored.[64]

The cruiser was ready for action by mid-January 1945, when she was sent to bombard Soviet forces in Samland.[71] The ship fired 871 rounds of ammunition at the Soviets advancing on the German bridgehead at Cranz held by the XXVIII Corps, which was protecting Königsberg. She was supported in this operation by the destroyer Z25 and torpedo boat T33.[68] At that point, Prinz Eugen had expended her main battery ammunition, and critical munition shortages forced the ship to remain in port until 10 March, when she bombarded Soviet forces around Gotenhafen, Danzig, and Hela. During these operations, she fired a total of 2,025 shells from her 20.3 cm guns and another 2,446 rounds from her 10.5 cm guns. The old battleship Schlesien also provided gunfire support, as did Lützow after 25 March. The ships were commanded by Vizeadmiral Bernhard Rogge.[68][72]

The following month, on 8 April, Prinz Eugen and Lützow steamed to Swinemünde.[67] On 13 April, 34 Lancaster bombers attacked the two ships while in port. Thick cloud cover forced the British to abort the mission and return two days later. On the second attack, they succeeded in sinking Lützow with a single Tallboy bomb hit.[73] Prinz Eugen then departed Swinemünde for Copenhagen,[67] arriving on 20 April. Once there, she was decommissioned on 7 May and turned over to Royal Navy control the following day.[72] For his leadership of Prinz Eugen in the final year of the war, Reinicke was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 21 April 1945.[74] During her operational career with the Kriegsmarine, Prinz Eugen lost 115 crew members; 79 men were killed in action, 33 were killed in accidents and three died of other causes. Of these 115 crew members, four were officers, seven were cadets or ensigns, two were petty officers, 22 were junior petty officers, 78 were sailors and two were civilians.[65]

Service with the United States Navy

On 27 May 1945, Prinz Eugen and the light cruiser Nürnberg—the only major German naval vessels to survive the war in serviceable condition—were escorted by the British cruisers Dido and Devonshire to Wilhelmshaven. On 13 December, Prinz Eugen was awarded as a war prize to the United States, which sent the ship to Wesermünde.[67] The United States did not particularly want the cruiser, but it did want to prevent the Soviet Union from acquiring it.[75] Her US commander, Captain Arthur H. Graubart, recounted later how the British, Soviet and US representatives in the Control Commission all claimed the ship and how in the end the various large prizes were divided in three lots, Prinz Eugen being one of them. The three lots were then drawn lottery style from his hat with the British and Soviet representatives drawing the lots for other ships and Graubart being left with the lot for Prinz Eugen.[76] The cruiser was commissioned into the US Navy as the unclassified miscellaneous vessel USS Prinz Eugen with the hull number IX-300. A composite American-German crew consisting of 574 German officers and sailors, supervised by eight American officers and eighty-five enlisted men under the command of Graubart,[77][78] then took the ship to Boston, departing on 13 January 1946 and arriving on 22 January.[67]

After arriving in Boston, the ship was extensively examined by the US Navy.[72] Her very large GHG passive sonar array was removed and installed on the submarine USS Flying Fish for testing.[79] American interest in magnetic amplifier technology increased again after findings in investigations of the fire control system of Prinz Eugen.[80][81] The guns from turret Anton were removed while in Philadelphia in February.[82] On 1 May the German crewmen left the ship and returned to Germany. Thereafter, the American crew had significant difficulties in keeping the ship's propulsion system operational—eleven of her twelve boilers failed after the Germans departed. The ship was then allocated to the fleet of target ships for Operation Crossroads in Bikini Atoll. Operation Crossroads was a major test of the effects of nuclear weapons on warships of various types. The trouble with Prinz Eugen's propulsion system may have influenced the decision to dispose of her in the nuclear tests.[78][83]

She was towed to the Pacific via Philadelphia and the Panama Canal,[78] departing on 3 March.[82] The ship survived two atomic bomb blasts: Test Able, an air burst on 1 July 1946 and Test Baker, a submerged detonation on 25 July.[84] Prinz Eugen was moored about 1,200 yards (1,100 m) from the epicenter of both blasts and was only lightly damaged by them;[85] the Able blast only bent her foremast and broke the top of her main mast.[86] She suffered no significant structural damage from the explosions but was thoroughly contaminated with radioactive fallout.[84] The ship was towed to the Kwajalein Atoll in the central Pacific, where a small leak went unrepaired due to the radiation danger.[87] On 29 August 1946, the US Navy decommissioned Prinz Eugen.[84]

By late December 1946, the ship was in very bad condition; on 21 December, she began to list severely.[78] A salvage team could not be brought to Kwajalein in time,[84] so the US Navy attempted to beach the ship to prevent her from sinking, but on 22 December, Prinz Eugen capsized and sank.[78] Her main battery gun turrets fell out of their barbettes when the ship rolled over. The ship's stern, including her propeller assemblies, remains visible above the surface of the water.[87] The US government denied salvage rights on the grounds that it did not want the contaminated steel entering the market.[84] In August 1979, one of the ship's screw propellers was retrieved and placed in the Laboe Naval Memorial in Germany.[8] The ship's bell is currently held at the National Museum of the United States Navy, while the bell from Tegetthoff is held in Graz, Austria.[65]

Beginning in 1974, the US government began to warn about the danger of an oil leak from the ship's full fuel bunkers. The government was concerned about the risk of a severe typhoon damaging the wreck and causing a leak. Starting in February 2018, the US Navy, including the Navy's Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit One, US Army, and the Federated States of Micronesia conducted a joint oil removal effort with the salvage ship USNS Salvor, which had cut holes into the ship's fuel tanks to pump the oil from the wreck directly into the oil tanker Humber.[88] The US Navy announced that the work had been completed by 15 October 2018; the project had extracted approximately 250,000 US gallons (950,000 l; 210,000 imp gal) of fuel oil, which amounted to 97 percent of the fuel remaining aboard the wreck. Lieutenant Commander Tim Emge, the officer responsible for the salvage operation, stated that "There are no longer active leaks...the remaining oil is enclosed in a few internal tanks without leakage and encased by layered protection."[89]

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prinz Eugen. |

Notes

- "L/60" denotes the length of the gun. The length of 60 caliber gun is 60 times its bore diameter.

- The British were unaware that the German ships had reversed positions while in the Denmark Strait. Observers on Prince of Wales correctly identified the ships, but failed to inform Admiral Holland. See Zetterling & Tamelander, p. 165.

Citations

- Williamson, pp. 4–5.

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 9.

- Busch, p. 10.

- Gröner, p. 65.

- Gröner, p. 66.

- Williamson, p. 37.

- Schmalenbach, pp. 121–122.

- Gröner, p. 67.

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 146.

- Williamson, p. 35.

- Williamson, pp. 37–38.

- Williamson, p. 38.

- Schmalenbach, p. 140.

- von Müllenheim-Rechberg, p. 60.

- von Müllenheim-Rechberg, p. 76.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 214.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 65.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 66–67.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 68.

- Zetterling & Tamelander, p. 114.

- von Müllenheim-Rechberg, p. 83.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 71.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 72.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 215.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 216.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 126.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 126–127.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 127.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 129–130.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 133–134.

- Garzke & Dulin, pp. 219–220.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 220.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 151–153.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 153.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 155–156.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 223.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 162–165.

- Bercuson & Herwig, pp. 165–166.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 167.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 168.

- Bercuson & Herwig, p. 173.

- Zetterling & Tamelander, pp. 192–193.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 227.

- Schmalenbach, p. 141.

- Busch, p. 93.

- Busch, p. 97.

- Busch, p. 104.

- Busch, p. 108.

- Williamson, p. 39.

- Busch, pp. 108–109.

- Busch, p. 117.

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 150.

- Busch, pp. 113–118.

- Garzke & Dulin, p. 146.

- Williamson, pp. 39–40.

- Williamson, p. 40.

- Hooton, pp. 114–115.

- Hooton, p. 114.

- Weal, p. 17.

- Schmalenbach, p. 142.

- Busch, p. 145.

- Rohwer, p. 146.

- Busch, pp. 157–160.

- Williamson, p. 41.

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 160.

- Koop & Schmolke, pp. 182–183.

- Schmalenbach, p. 143.

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 154.

- Rohwer, p. 351.

- Rohwer, p. 363.

- Williamson, pp. 41–42.

- Williamson, p. 42.

- Rohwer, p. 409.

- Dörr, p. 169.

- Delgado, p. 44.

- Busch, pp. 212–213.

- Slavick, p. 245.

- "Prinz Eugen". Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Friedman, p. 62.

- Geyger, p. 11.

- Black, pp. 427–435.

- Roberts, p. 60.

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 159.

- Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 229.

- Roberts, p. 59.

- Roberts, p. 65.

- Lenihan, p. 200.

- Mizokami.

- Shavers.

References

- Bercuson, David J. & Herwig, Holger H. (2003). The Destruction of the Bismarck. New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-397-1.

- Black, A. O. (November 1948). "Effect of Core Material on Magnetic Amplifier Design". Proceedings of the National Electronics Conference. 4: 427–435.

- Busch, Fritz-Otto (1975). Prinz Eugen. London: First Futura Publications. ISBN 0-8600-72339.

- Delgado, James P. (1996). Ghost fleet: the sunken ships of Bikini Atoll. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1864-7.

- Dörr, Manfred (1996). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Überwasserstreitkräfte der Kriegsmarine—Band 2: L–Z [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the Surface Forces of the Navy—Volume 2: L–Z] (in German). Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2497-6.

- Friedman, Norman (1994). U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-260-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-913-9.

- Garzke, William H. & Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Geyger, William A. (1957) [1954]. "Historical Development of Magnetic-amplifier Circuits". Magnetic-Amplifier Circuits (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. p. 11. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 56-12532.

One reason for the increased interest in magnetic amplifiers in this country was the successful German development work for various military applications, especially for naval fire-control systems, as used on the German heavy cruiser "Prinz Eugen."

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hooton, E. R. (1997). Eagle in Flames: The Fall of the Luftwaffe. London: Brockhampton. ISBN 978-1-86019-995-0.

- Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (1992). Die Schweren Kreuzer der Admiral Hipper-Klasse [The Heavy Cruisers of the Admiral Hipper Class] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5896-8.

- Lenihan, Daniel (2003). Submerged: Adventures of America's Most Elite Underwater Archeology Team. New York: Newmarket. ISBN 978-1-55704-589-8.

- Mizokami, Kyle (17 September 2018). "The U.S. Nuked This Warship in 1946. Now America Is Trying To Save Its Oil Before It's Too Late". popularmechanics.com. Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Roberts, John, ed. (1979). "Warship Pictorial: Prinz Eugen". Warship. London: Conway Press. III: 59–65. ISBN 978-0-85177-204-2.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Schmalenbach, Paul (1971). "KM Prinz Eugen". Warship Profile 6. Windsor: Profile Publications. pp. 121–144. OCLC 10095330.

- Shavers, Clyde (15 October 2018). "U.S. Navy divers recover oil from wrecked WWII ship Prinz Eugen". www.cfp.navy.mil. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Slavick, Joseph P. (2003). The Cruise of the German Raider Atlantis. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-537-8.

- Weal, John (1996). Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Aces of the Western Front. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-85532-595-1.

- Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Heavy Cruisers 1939–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-502-0.

- von Müllenheim-Rechberg, Burkhard (1980). Battleship Bismarck, A Survivor's Story. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-096-9.

- Zetterling, Niklas & Tamelander, Michael (2009). Bismarck: The Final Days of Germany's Greatest Battleship. Drexel Hill: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-04-0.

Further reading

- Burdick, Charles Burton (1996). The End of the Prinz Eugen (IX300). Menlo Park: Markgraf Publications Group. ISBN 0944109101.