HMS Prince of Wales (53)

HMS Prince of Wales was a King George V-class battleship of the Royal Navy, built at the Cammell Laird shipyard in Birkenhead, England. She had an extensive battle history, first seeing action in August 1940 while still being outfitted in her drydock when she was attacked and damaged by German aircraft. In her brief but storied career, she was involved in several key actions of the Second World War, including the May 1941 Battle of the Denmark Strait against the German battleship Bismarck, escorting one of the Malta convoys in the Mediterranean, and then attempting to intercept Japanese troop convoys off the coast of Malaya when she was sunk on 10 December 1941. In her final battle, which was three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, she was sunk alongside the battlecruiser HMS Repulse by Japanese bombers when they became the first capital ships to be sunk solely by air power on the open sea, a harbinger of the diminishing role this class of ships was subsequently to play in naval warfare. The wreck of Prince of Wales lies upside down in 223 feet (68 m) of water, near Kuantan, in the South China Sea.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Prince of Wales |

| Ordered: | 29 July 1936 |

| Builder: | Cammell Laird and Company, Ltd., Birkenhead |

| Laid down: | 1 January 1937 |

| Launched: | 3 May 1939 |

| Completed: | 31 March 1941 |

| Commissioned: | 19 January 1941 |

| Identification: | Pennant number: 53 |

| Motto: | "Ich Dien" – German: "I serve" |

| Nickname(s): | PoW |

| Fate: | Sunk on 10 December 1941 by Japanese air attack off Kuantan, South China Sea |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | King George V-class battleship |

| Displacement: | 43,786 tons (deep) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 103 ft 2 in (31.4 m) |

| Draught: | 34 ft 4 in (10.5 m) |

| Installed power: | 110,000 shp (82,000 kW) |

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 28.3 knots (52.4 km/h; 32.6 mph) |

| Range: | 15,600 nmi (28,900 km; 18,000 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 1,521 (1941) |

| Sensors and processing systems: | |

| Armament: | |

| Armour: | |

| Aircraft carried: | 4 Supermarine Walrus seaplanes, 1 double-ended catapult |

Construction

In the aftermath of the First World War, the Washington Naval Treaty was drawn up in 1922 in an effort to stop an arms race developing between Britain, Japan, France, Italy and the United States. This treaty limited the number of ships each nation was allowed to build, and capped the tonnage of all capital ships at 35,000 tons.[3] These restrictions were extended in 1930 through the Treaty of London, however, by the mid-1930s Japan and Italy had withdrawn from both of these treaties, and the British became concerned about a lack of modern battleships within their navy. As a result, the Admiralty ordered the construction of a new battleship class: the King George V class. Due to the provisions of both the Washington Naval Treaty and the Treaty of London, both of which were still in effect when the King George Vs were being designed, the main armament of the class was limited to the 14-inch (356 mm) guns prescribed under these instruments. They were the only battleships built at that time to adhere to the treaty, and even though it soon became apparent to the British that the other signatories to the treaty were ignoring its requirements, it was too late to change the design of the class before they were laid down in 1937.[4]

Prince of Wales was originally named King Edward VIII but upon the abdication of Edward VIII the ship was renamed even before she had been laid down. This occurred at Cammell Laird's shipyard in Birkenhead on 1 January 1937, although it was not until 3 May 1939 that she was launched. She was still fitting out when war was declared in September, causing her construction schedule, and that of her sister, King George V, to be accelerated. Nevertheless, the late delivery of gun mountings caused delays in her outfitting.[5]

During early August 1940, while she was still being outfitted and was in a semi-complete state, Prince of Wales was attacked by German aircraft. One bomb fell between the ship and a wet basin wall, narrowly missing a 100-ton dockside crane, and exploded underwater below the bilge keel. The explosion took place about six feet from the ship's port side in the vicinity of the after group of 5.25-inch guns. Buckling of the shell plating took place over a distance of 20 to 30 feet (9.1 m), rivets were sprung and considerable flooding took place in the port outboard compartments in the area of damage, causing a ten-degree port list. The flooding was severe, due to the fact that final compartment air tests had not yet been made and the ship did not have her pumping system in operation.[5]

The water was pumped out through the joint efforts of a local fire company and the shipyard, and Prince of Wales was later dry docked for permanent repairs. This damage and the problem with the delivery of her main guns and turrets delayed her completion. As the war progressed there was an urgent need for capital ships, and so her completion was advanced by postponing compartment air tests, ventilation tests and a thorough testing of her bilge, ballast and fuel-oil systems.[5]

Description

Prince of Wales displaced 36,727 long tons (37,300 t) as built and 43,786 long tons (44,500 t) fully loaded. The ship had an overall length of 745 feet (227.1 m), a beam of 103 feet (31.4 m) and a draught of 29 feet (8.8 m). Her designed metacentric height was 6 feet 1 inch (1.85 m) at normal load and 8 feet 1 inch (2.46 m) at deep load.[6][7]

She was powered by Parsons geared steam turbines, driving four propeller shafts. Steam was provided by eight Admiralty boilers which normally delivered 100,000 shaft horsepower (75,000 kW), but could deliver 110,000 shp (82,000 kW) at emergency overload.[N 1] This gave Prince of Wales a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph).[4][10] The ship carried 3,542 long tons (3,600 t) of fuel oil.[11] She also carried 180 long tons (200 t) of diesel oil, 256 long tons (300 t) of reserve feed water and 444 long tons (500 t) of freshwater.[11] During full-power trials on 31 March 1941, Prince of Wales at 42,100 tons displacement achieved 28 knots with 111,600 shp at 228 rpm and a specific fuel consumption of 0.73 lb per shp.[12] Prince of Wales had a range of 3,100 nautical miles (5,700 km; 3,600 mi) at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph).[1]

Armament

Prince of Wales mounted 10 BL 14-inch (356 mm) Mk VII guns. The 14-inch guns were mounted in one Mark II twin turret forward and two Mark III quadruple turrets, one forward and one aft. The guns could be elevated 40 degrees and depressed 3 degrees. Training arcs were: turret "A", 286 degrees; turret "B", 270 degrees; turret "Y", 270 degrees. Training and elevating was done by hydraulic drives, with rates of two and eight degrees per second, respectively. A full gun broadside weighed 15,950 pounds (7,230 kg), and a salvo could be fired every 40 seconds.[13] The secondary armament consisted of 16 QF 5.25-inch (133 mm) Mk I guns which were mounted in eight twin mounts, weighing 81 tons each.[14] The maximum range of the Mk I guns was 24,070 yards (22,009.6 m) at a 45-degree elevation, the anti-aircraft ceiling was 49,000 feet (14,935.2 m). The guns could be elevated to 70 degrees and depressed to 5 degrees.[15] The normal rate of fire was ten to twelve rounds per minute, but in practice the guns could only fire seven to eight rounds per minute.[14] Along with her main and secondary batteries, Prince of Wales carried 32 QF 2 pdr (1.575-inch, 40.0 mm) Mk.VIII "pom-pom" anti-aircraft guns. She also carried 80 UP projectors, which were short range rocket firing anti-aircraft weapons used extensively in the early days of the Second World War by the Royal Navy.[1]

Operational service

Action with Bismarck

On 22 May 1941, Prince of Wales, the battlecruiser Hood and six destroyers were ordered to take station south of Iceland and intercept the German battleship Bismarck if she attempted to break out into the Atlantic. Captain John Leach knew that main-battery breakdowns were likely to occur, since Vickers-Armstrongs technicians had already corrected some that took place during training exercises in Scapa Flow. These technicians were personally requested by the captain to remain aboard. They did so and played an important role in the resulting action.[16]

The next day Bismarck, in company with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, was reported heading south-westward in the Denmark Strait. At 20:00 Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland, in his flagship Hood, ordered the force to steam at 27 knots (50 km/h), which it did most of the night. His battle plan called for Prince of Wales and Hood to concentrate on Bismarck, while the cruisers Norfolk and Suffolk would handle Prinz Eugen. However the two cruisers were not informed of this plan because of strict radio silence. At 02:00, on 24 May, the destroyers were sent as a screen to search for the German ships to the north, and at 02:47 Hood and Prince of Wales increased speed to 28 knots (52 km/h) and changed course slightly to obtain a better target angle on the German ships. The weather improved, with 10-mile (16 km) visibility, and crews were at action stations by 05:10.[16]

At 05:37 an enemy contact report was made, and course was changed to starboard to close range. Neither ship was in good fighting trim. Hood, designed twenty-five years earlier, lacked adequate decking armour and would have to close the range quickly, as she would become progressively less vulnerable to plunging shellfire at shorter ranges. She had completed an overhaul in March and her crew had not been adequately retrained. Prince of Wales, with thicker armour, was less vulnerable to 15-inch shells at ranges greater than 17,000 feet (5,200 m), but her crew had also not been trained to battle efficiency. The British ships made their last course change at 05:49, but they had made their approach too fine (the German ships were only 30 degrees on the starboard bow) and their aft turrets could not fire. Prinz Eugen, with Bismarck astern, had Prince of Wales and Hood slightly forward of the beam, and both ships could deliver full broadsides.[17]

At 05:53, despite seas breaking over the bows, Prince of Wales opened fire on Bismarck at 26,500 yards (24,200 m).[18] There was some confusion among the British as to which ship was Bismarck and thirty seconds earlier Hood had mistakenly opened fire on Prinz Eugen as the German ships had similar profiles. Hood's first salvo straddled the enemy ship, but Prinz Eugen, in less than three minutes, scored 8-inch-shell hits on Hood. The first shots by Prince of Wales – two three-gun salvoes at ten second intervals – were 1,000 yards over.[17] The turret rangefinders on Prince of Wales could not be used because of spray over the bow and fire was instead directed from the 15-foot (4.6 m) rangefinders in the control tower.[19]

The sixth, ninth and thirteenth salvos were straddles[18] and two hits were made on Bismarck. One shell holed her bow and caused Bismarck to lose 1,000 tons of fuel oil, mostly to salt-water contamination. The other fell short, and entered Bismarck below her side armour belt, the shell exploded and flooded the auxiliary boiler machinery room and forced the shutdown of two boilers due to a slow leak in the boiler room immediately aft. The loss of fuel and boiler power were decisive factors in the Bismarck's decision to return to port.[20] In Prince of Wales, "A1" gun ceased fire after the first salvo due to a defect.[18] Sporadic breakdowns occurred until the decision to turn away was made, and during the turn "Y" turret jammed.[18]

Both German ships initially concentrated their fire on Hood and destroyed her with salvoes of 8- and 15-inch shells. An 8-inch shell hit the boat deck and struck a ready service locker for the UP rocket projectors, and a fire blazed high above the first superstructure deck. At 05:58 at a range of 16,500 yards (15,100 m), the force commander ordered a turn of 20 degrees to port to open the range and bring the full battery of the British ships to bear on Bismarck. As the turn began, Bismarck straddled Hood with her third and fourth four-gun salvoes and at 06:01 the fifth salvo hit her, causing a large explosion. Flames shot up near Hood's masts, then an orange-coloured fireball and an enormous smoke cloud obliterated the ship. On Prince of Wales, it seemed that Hood collapsed amidships, and the bow and stern could be seen rising as she rapidly settled. Prince of Wales made a sharp starboard turn to avoid hitting the debris and in doing so further closed the range between her and the German ships. In the four-minute action, Hood, the largest battlecruiser in the world, had been sunk. 1,419 officers and men were killed. Only three men survived.[19]

Prince of Wales fired unopposed until she began a port turn at 05:57, when Prinz Eugen took her under fire. After Hood exploded at 06:01, the Germans opened intense and accurate fire on Prince of Wales, with 15-inch, 8-inch and 5.9-inch guns. A heavy hit was sustained below the waterline as Prince of Wales manoeuvred through the wreckage of Hood. At 06:02, a 15-inch shell struck the starboard side of the compass platform and killed the majority of the personnel there. The navigating officer was wounded, but Captain Leach was unhurt. Casualties were caused by the fragments from the shell's ballistic cap and the material it dislodged in its diagonal path through the compass platform.[19] A 15-inch diving shell penetrated the ship's side below the armour belt amidships, failed to explode and came to rest in the wing compartments on the starboard side of the after boiler rooms. The shell was discovered and defused when the ship was docked at Rosyth.[21]

At 06:05 Captain Leach decided to disengage and laid down a heavy smokescreen to cover Prince of Wales's escape. Following this, Leach radioed the Norfolk that Hood had been sunk and then proceeded to join Suffolk roughly 15 to 17 miles (24 to 27 km) astern of Bismarck. Throughout the day the British ships continued to chase Bismarck until at 18:16 when Suffolk sighted the German battleship at 22,000 yards (20,000 m). Prince of Wales then opened fire on Bismarck at an extreme range of 30,300 yards (27,700 m), she fired 12 salvos but all of them missed. At 01:00 on 25 May Prince of Wales once again regained contact and opened fire at a radar range of 20,000 yards (18,000 m), after observers believed that she had scored a hit on Bismarck, Prince of Wales's "A" turret temporarily jammed, leaving her with only six operational guns.[18] After losing Bismarck owing to poor visibility and after searching for 12 hours, Prince of Wales headed for Iceland and took no further part in actions against Bismarck.[22]

Atlantic Charter meeting

_off_Argentia%252C_Newfoundland%252C_in_August_1941_(NH_67194-A).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Following repairs at Rosyth, Prince of Wales transported Prime Minister Winston Churchill across the Atlantic for a secret conference with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[23] On 5 August Roosevelt boarded the cruiser USS Augusta from the presidential yacht Potomac. Augusta proceeded from Massachusetts to Placentia Bay and Argentia in Newfoundland with the cruiser USS Tuscaloosa and five destroyers, arriving on 7 August while the presidential yacht played a decoy role by continuing to cruise New England waters as if the President were still on board. On 9 August Churchill arrived in the bay aboard Prince of Wales, escorted by the destroyers HMS Ripley, HMCS Assiniboine and HMCS Restigouche.[24] At Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, Roosevelt transferred to the destroyer USS McDougal to meet Churchill on board Prince of Wales. The conference continued from 10 to 12 August aboard Augusta and, at the end of the conference, the Atlantic Charter was proclaimed.[25] Following the declaration of the charter, Prince of Wales arrived back at Scapa Flow on 18 August.[23]

Mediterranean duty

In September 1941, Prince of Wales was assigned to Force H, in the Mediterranean. On 24 September Prince of Wales formed part of Group II, led by Vice-Admiral Alban Curteis and consisting of the battleships Prince of Wales and Rodney, the cruisers Kenya, Edinburgh, Sheffield and Euryalus, and twelve destroyers. The force provided an escort for Operation Halberd, a supply convoy from Gibraltar to Malta.[26] On 27 September the convoy was attacked by Italian aircraft, with Prince of Wales shooting down several with her 5.25-inch (133 mm) guns.[9] Later that day there were reports that units of the Italian Fleet were approaching. Prince of Wales, the battleship Rodney and the aircraft carrier Ark Royal were despatched to intercept, but the search proved fruitless. The convoy arrived in Malta without further incident, and Prince of Wales returned to Gibraltar, before sailing on to Scapa Flow, arriving there on 6 October.[23]

Far East

On 25 October Prince of Wales and a destroyer escort left home waters bound for Singapore, there to rendezvous with the battlecruiser Repulse and the aircraft carrier Indomitable. Indomitable however ran aground off Jamaica a few days later and was unable to proceed. Calling at Freetown and Cape Town South Africa to refuel and generate publicity, Prince of Wales also stopped in Mauritius and the Maldive Islands. Prince of Wales reached Colombo, Ceylon, on 28 November, joining Repulse the next day. On 2 December the fleet docked in Singapore.[23] Prince of Wales then became the flagship of Force Z, under the command of Admiral Sir Tom Phillips.[27] Admiral of the Home Fleet Sir John Tovey was opposed to sending any of the new King George V battleships as he believed that they were not suited to operating in tropical climates.[28]

Japanese troop-convoys were first sighted on 6 December. Two days later, Japanese aircraft raided Singapore; although the Prince of Wales's anti-aircraft batteries opened fire, they scored no hits and had no effect on the Japanese aircraft. A signal was received from the Admiralty in London ordering the British squadron to commence hostilities, and that evening, confident that a protective air umbrella would be provided by the RAF presence in the region, Admiral Phillips set sail. Force Z at this time comprised the battleship Prince of Wales, the battlecruiser Repulse, and the destroyers Electra, Express, Tenedos and HMAS Vampire.[29]

The object of the sortie was to attack Japanese transports at Kota Bharu, but in the afternoon of 9 December the Japanese submarine I-65 spotted the British ships, and in the evening they were detected by Japanese aerial reconnaissance. By this time it had been made clear that no RAF fighter support would be forthcoming. At midnight a signal was received that Japanese forces were landing at Kuantan in Malaya. Force Z was diverted to investigate. At 02:11 on 10 December the force was again sighted by a Japanese submarine and at 08:00 arrived off Kuantan, only to discover that the reported landings were a diversion.[29]

At 11:00 that morning the first Japanese air attack began. Eight Type 96 "Nell" bombers dropped their bombs close to Repulse, one passing through the hangar roof and exploding on the 1-inch plating of the main deck below. The second attack force, comprising seventeen "Nells" armed with torpedoes, arrived at 11:30, divided into two attack formations. Despite reports to the contrary, Prince of Wales was struck by only one torpedo.[30][31] Meanwhile, Repulse avoided the seven torpedoes aimed at her, as well as bombs dropped by six other "Nells" a few minutes later.

The torpedo struck Prince of Wales on the port side aft, abaft "Y" Turret, wrecking the outer propeller shaft on that side and destroying bulkheads to one degree or another along the shaft all the way to B Engine Room. This caused rapid uncontrollable flooding[31] and put the entire electrical system in the after part of the ship out of action. Lacking effective damage control, she soon took on a heavy list.[32]

A third torpedo attack developed against Repulse and once again she avoided taking any hits.

A fourth attack, conducted by torpedo-carrying Type 1 "Bettys", developed. This one scored hits on Repulse and she sank at 12:33. Six aircraft from this wave also attacked Prince of Wales, hitting her with three torpedoes,[30][31] causing further damage and flooding. Finally, a 500-kilogram (1,100 lb) bomb hit Prince of Wales's catapult deck, penetrated to the main deck, where it exploded, causing many casualties in the makeshift aid centre in the Cinema Flat. Several other bombs from this attack scored very 'near misses', indenting the hull, popping rivets and causing hull plates to 'split' along the seams and intensifying the flooding.[31] At 13:15 the order to abandon ship was given, and at 13:20 Prince of Wales capsized and sank; Admiral Phillips and Captain Leach were among the 327 fatalities.[32]

Aftermath

Prince of Wales and Repulse were the first capital ships to be sunk solely by naval air power on the open sea (albeit by land-based rather than carrier-based aircraft), a harbinger of the diminishing role this class of ships was to play in naval warfare thereafter. It is often pointed out, however, that contributing factors to the sinking of Prince of Wales were her surface-scanning radars being inoperable in the humid tropic climate, depriving Force Z of one of its most potent early-warning devices and the critical early damage she sustained from the first torpedo. Another factor which led to Prince of Wales's demise was the loss of her dynamos, depriving Prince of Wales of many of her electric pumps. Further electrical failures left parts of the ship in total darkness, and added to the difficulties of her damage repair parties as they attempted to counter the flooding.[33] The sinking was the subject of an inquiry chaired by Mr. Justice Bucknill, but the true causes of the ship's loss were only established when divers examined the wreck after the war. The Director of Naval Construction's report on the sinking claimed that the ship's anti-aircraft guns could have "inflicted heavy casualties before torpedoes were dropped, if not preventing the successful conclusion of attack had crews been more adequately trained in their operation.[34][28]

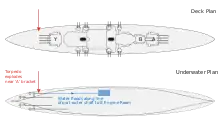

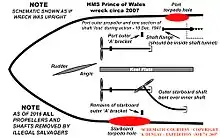

The wreck

The wreck lies upside down in 223 feet (68 m) of water at 3°33′36″N 104°28′42″E. A Royal Navy White Ensign attached to a line on a buoy tied to a propeller shaft is periodically renewed. The wreck site was designated a 'Protected Place' in 2001 under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, just prior to the 60th anniversary of her sinking. The ship's bell was manually raised in 2002 by British technical divers with the permission of the Ministry of Defence and blessing of the Force Z Survivors Association. It was restored, then presented for display by First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff, Admiral Sir Alan West, to the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool. The bell has been since moved to the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth for display in the Hear My Story Galleries.

In May 2007, Expedition 'Job 74',[30] a dedicated survey of the exterior hull of both Prince of Wales and Repulse, was conducted. The expedition's findings sparked considerable interest among naval architects and marine engineers around the world; as they detailed the nature of the damage to Prince of Wales and the exact location and number of torpedo hits. Consequently, the findings contained in the initial expedition report[30] and later supplementary reports[35][36] were analysed by the SNAME (Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers)[37] Marine Forensics Committee, and a resultant paper was drawn up entitled Death of a Battleship: A Re-analysis of the Tragic Loss of HMS Prince of Wales, and was subsequently presented at a meeting of RINA (Royal Institution of Naval Architects)[38] and IMarEST (Institute of Marine Engineering, Science & Technology)[39] members in London in 2009 by Mr. William Garzke. This report was also presented to the IMarEST, this time in New York, in 2011. However, in 2012 the original paper was updated and expanded (and renamed Death of a Battleship: The Loss of HMS Prince of Wales. A Marine Forensics Analysis of the Sinking[31]) in light of a subsequent diver being able to penetrate deep into the port outer propeller shaft tunnel with a high definition camera, taking photos along the entire length of the propeller shaft all the way to the aft bulkhead of 'B' Engine Room.

In October 2014, the Daily Telegraph reported that both Prince of Wales and Repulse were being "extensively damaged" with explosives by scrap metal dealers.[40]

It is currently traditional for every passing Royal Navy ship to perform a remembrance service over the site of the wrecks.[41]

Refits

During her career, Prince of Wales was refitted on several occasions, to bring her equipment up to date. The following are the dates and details of the refits undertaken.[42]

| Dates | Location | Description of Work |

|---|---|---|

| May 1941 | Rosyth | 4 × Type 282 radar and 4 × Type 285 radar added.[43] |

| June–July 1941 | Rosyth | UP projectors removed. 2 × 8-barrelled and 1 × 4-barrelled 2-pdr pom-poms added. Type 271 radar added.[43][44] |

| November 1941 | Cape Town | 7 × single 20 mm added.[43] |

References

Notes

- The King George V-class battleships had their steam plant specifications revised during the building phase, and as built the ships actually produced 110,000 shp at 230 rpm, and were designed for an overload power of 125,000 shp, which was exceeded in service.[8][9]

Citations

- Chesneau p. 6

- Konstam p. 22

- Raven and Roberts, p. 107

- Konstam, p. 20

- Garzke p. 177

- Chesneau (Conways) p. 15

- Garzke p. 249

- Raven and Roberts pp. 284, 304

- Garzke p. 191

- Garzke p. 238

- Garzke p. 253

- Brown 1995, p. 28.

- Garzke p. 227

- Garzke p. 229

- Garzke p. 228

- Garzke pp. 177–79

- Garzke p. 179

- ADM 234/509

- Garzke p. 180

- Asmussen, John. The Bismarck Escapes

- Raven and Roberts p. 351

- Garzke p. 190

- Chesneau p. 12

- Rohwer p. 90

- Rohwer p. 91

- Rohwer p. 103

- Dull, p. 36

- Chesneau, pp. 12–13

- Denlay, Kevin. "Expedition 'Job 74' survey report" (PDF). Explorers.org. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, Robert; Denlay, Kevin: Death of a Battleship: The Loss of HMS Prince of Wales. A Marine Forensics Analysis of the Sinking https://www.pacificwrecks.com/ships/hms/prince_of_wales/death-of-a-battleship-2012-update.pdf

- Chesneau, p. 13

- Garzke p. 206

- "Loss of HMS Prince of Wales: reports of 2nd Bucknill Committee, etc". The Admiralty. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- Denlay, Kevin. "HMS Prince of Wales – Stern Damage Survey" (PDF). Pacific Wrecks.com. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Denlay, Kevin. "Description of the Lower Hull Indentation Damage on the Prince of Wales" (PDF). Pacific Wrecks.com. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Home – Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers. Sname.org. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- The Royal Institution of Naval Architects. RINA. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- The IMarEST. The IMarEST. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- Julian Ryall, Tokyo; Joel Gunter (25 October 2014). "Celebrated British warships being stripped bare for scrap metal". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Rasor p. 98

- Chesneau p. 52

- Konstam p. 37

- Chesneau p. 53

Bibliography

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battlecruisers 1905–1970. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-07247-3.

- Brown, D. K. (1995). The Design And Construction Of British Warships 1939–1945. 1: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-160-2.

- Cain, Timothy (1959). HMS Electra. Frederick Muller. ISBN 0-86007-330-0.

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War Two. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87021-459-4.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Chesneau, Roger (2004). King George V Battleships. ShipCraft. 2. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-211-9.

- Dull, Paul (2007). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941–1945). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-219-5.

- Garzke, William H., Jr.; Dulin, Robert O., Jr. (1980). British, Soviet, French, and Dutch Battleships of World War II. London: Jane's. ISBN 978-0-7106-0078-3.

- Hack, Karl; Blackburn, Kevin (2004). Did Singapore Have to Fall?: Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30803-8.

- Hein, David. "Vulnerable: HMS Prince of Wales in 1941". Journal of Military History 77, no. 3 (July 2013): 955–989. Abstract online: http://www.smh-hq.org/jmh/jmhvols/773.html

- Horodyski, Joseph M. Military Heritage 3, no. 3 (December 2001): 69–77.

- Hough, Richard (1963). Death of the Battleship. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 396061.

- Konstam, Angus (2009). British Battleships 1939–45 (2): Nelson and King George V classes. New Vanguard. 160. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-389-6.

- Middlebrook, Martin (1979). The Sinking of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse. Penguin History. ISBN 0-7139-1042-9.

- Rasor, Eugene L. (1998). The China-Burma-India Campaign, 1931–1945: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28872-0.

- Raven, Alan; Roberts, John (1976). British Battleships of World War Two: The Development and Technical History of the Royal Navy's Battleships and Battlecruisers from 1911 to 1946. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-85368-141-0.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Stephen, Martin; Grove, Eric (1988). Sea Battles in Close-up: World War 2. 1. Shepperton, UK: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-1596-8.

Web

- Link to a wreck survey report compiled after Expedition 'Job 74', May 2007

- 2012 update analysis of the loss of Prince of Wales, by Garzke, Dulin and Denlay

- Description of lower hull indentation damage on wreck of HMS Prince of Wales

- SI 2008/0950 Current designation under Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

- Navy News 2001 Announcement of designation under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

- Link to a 2008 survey report, specifically regarding the stern torpedo damage to PoW.

- "ADM 234/509: H. M. S. Prince of Wales' Gunnery Aspects of the "Bismarck" Pursuit". The Admiralty. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- "ADM 116/4521: Loss of HMS Prince of Wales: reports of 2nd Bucknill Committee, etc". The Admiralty. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- Naval Staff History Second World War Battle Summary No. 14 (revised) Loss of H. M. Ships Prince of Wales and Repulse 10 December 1941.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Prince of Wales (ship, 1941). |

- List of Crew

- Newsreel footage of Operation Halberd, as filmed from Prince of Wales

- Photos of Prince of Wales at MaritimeQuest