Giralda

The Giralda (Spanish: La Giralda [la xiˈɾalda]) is the bell tower of Seville Cathedral in Seville, Spain.[1] It was built as the minaret for the Great Mosque of Seville in al-Andalus, Moorish Spain, during the reign of the Almohad dynasty, with a Renaissance-style top added by the Catholics after the expulsion of the Muslims from the area. Dating from the Reconquest of 1248 to the 16th century and built by the Moors. The Giralda was registered in 1987 as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, along with the Alcázar and the General Archive of the Indies. The tower is 104.1 m (342 ft) in height and remains one of the most important symbols of the city, as it has been since the Middle Ages.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

La Giralda | |

| Location | Seville, Spain |

| Part of | Seville Cathedral |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iii), (vi) |

| Reference | 383bis-001 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th session) |

| Extensions | 2010 |

| Coordinates | 37°23′10.3″N 5°59′32.7″W |

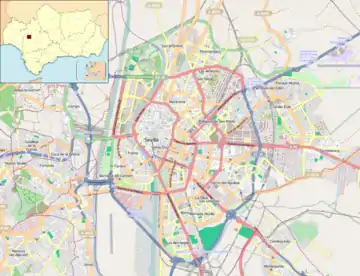

Location of Giralda in Seville  Giralda (Spain) | |

Origin

Initial construction

The mosque was built to replace the Umayyad mosque of 'Addabas, since the congregation had grown larger than the modest prayer hall could accommodate.[2][3] It was commissioned in 1171 by caliph Abu Ya'qub Yusuf .[2] Construction was slowed down by the redirection of an existing city sewer that needed to be moved to accommodate the broad foundation for the building, an engineering obstacle that slowed progress by four years.

From the beginning, craftsmen from all over Al-Andalus and the Maghrib were enlisted in the mosque's planning, construction, and decoration, and the caliph himself was highly invested in the process and was said to have visited the site daily.[2][3] By 1176, the mosque was complete, save for the minaret; however, Friday prayer was not held there until 1182, and it was not until 1184 when construction even began on the minaret.[2]

Building of the Minaret

Construction stalled once again in 1184 with the death of the architect, and a month and a half later, the caliph, who died while commanding the Siege of Santarém.[3] It was picked up four years later by the caliph's son, Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, aided by a group of architects and designers, including Sevillan architect Ahmad ibn Basuh and Sicilian architect Abu Layth Al-Siqilli.[3][4][2] The minaret was built using both local bricks and recycled marble from old Umayyad monuments.[3] On 10 March 1198, the tower was completed with the addition of four precious metal spheres (either gold or bronze) at the tower's peak to commemorate al-Mansur's victory over Alfonso VIII of Castile, which had taken place four years prior.[5][2]

Structure and decoration

Mosque interior

Before its partial destruction in a 1356 earthquake, the mosque was comparable in size to the great mosque of Cordoba and its walls faced the cardinal directions with mathematical preciseness.[6][2] The prayer hall was symmetrical and airy, with a still-extant courtyard, the Patio de los Naranjos, or "Courtyard of Orange Trees."[6] Its interior had a stucco-carved dome over the mihrab, as well as several matching carvings over the arched doorways.[2] The minbar was decorated in a Cordoban style, constructed from expensive wood and embellished with sandalwood, ivory, ebony, gold, and silver.[2]

The Giralda

The minaret, which still stands as the Giralda, contains a series of ramps winding around the perimeter of several vaulted chambers at the tower's core.[7] These ramps were designed with enough width and height to accommodate "beasts of burden, people, and the custodians," according to one chronicler from the era.[2] The decorated facades and windows on the tower are stepped to match the ramps in order to maximize light to the chambers inside.[7] This exterior brick decoration was mainly done by 'Ali al-Ghumari, a Berber craftsman who also did repair work on the interior.[2] The facades of the tower did contain some plaster embellishment, but they were removed during a modern restoration.[7]

The main gateway, still in existence, contains a metal-plated door with geometric decoration and floral knockers.[7]

Post-Al-Andalus

Conversion to cathedral

After Seville was recovered by the Christians in 1248 during the Reconquista, the city's mosque was symbolically converted into a cathedral. This involved changing the liturgical orientation, closing and screening off exits and archways, and creating several small family chapels. The former mosque was not well-maintained by any of the groups inhabiting their own sections of the building during this period, and most of the records from the 13th and early 14th centuries describe its neglect, damage, and consequent destruction to make way for a new cathedral.[6]

This structure was badly damaged in a 1356 earthquake, and by 1433 the city began building the current cathedral. Local stone to build with was scarce, and there were few skilled stonemasons in the area, so timber and stone had to be shipped from overseas, and like its earlier incarnation, the construction of the cathedral brought together artisans from all over its respective empire, this time as far away as Germany and the Netherlands. Construction took 73 years and was completed in 1506.[6]

Addition to tower

Today, the Giralda stands as one of the largest churches in the world and an example of the Gothic and Baroque architectural styles. The metal spheres that originally topped the tower fell during the earthquake, and the spheres were replaced with a cross and bell. The new cathedral incorporated the tower as a bell tower and eventually built it higher during the Renaissance under architect Hernán Ruiz the Younger, who was commissioned to work on the tower in 1568. This newer section of the tower contains a large inscription of Seville's motto, NO8DO, spoken No me ha dejado, meaning "[Seville] has not abandoned me." Alfonso X of Castile gave the motto to the city when it continued to support his rule during an insurrection. Covering the top of the tower is the "Lily section" which surrounds the enclosure with the bell. The statue stands 4 m (13 feet) in height – 7 m (23 ft) with the pedestal – and sit on top of the tower from its installation in 1568.

Dimensions

The base at street level is a square of 13.6 m on the side and which sits on a solid foundation which is a bit wider, 15~16 m and about 5 m deep. The foundation is built with solid, rectangular stones, some taken and reused from the Roman wall nearby.[8]

The part which corresponds to the original Moorish minaret is about 51 m high, with the Christian addition it is 98.5 m high and taking into account the wind vane it is 104 m high. The weather vane (giralda), which gives its name to the building, is over 4 m tall, 7 m including the base.

The tower has a ramp with 35 segments wide and tall enough to allow a person to ride on horseback to the top of the Moorish tower. The Christian addition has a final stair with 17 steps leading up to the bells.

Buildings inspired by the Giralda

Many towers have borrowed from the Giralda's design throughout history. Several church towers in the province of Seville also bear a resemblance to the tower, and may have been inspired by the Giralda. These towers, most notably those in Lebrija and Carmona, are popularly known as Giraldillas.

Numerous replicas of the Giralda have been built in the United States, mostly between 1890 and 1937:

- The second Madison Square Garden in New York City, designed by Stanford White, built in 1890

- A replica in the Country Club Plaza in Kansas City, Missouri

- The clock tower of the Ferry Building in San Francisco, completed in 1898

- The clock tower of the Railroad Depot in Minneapolis, destroyed by wind in 1941

- The Freedom Tower in Miami, Florida, built in 1925

- The Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables, Florida, built in 1926

- The Wrigley Building in Chicago, built in 1920

- The Terminal Tower in Cleveland, built in 1930

- The clock tower at the University of Puerto Rico's Río Piedras campus, built in 1937

The building has also inspired buildings outside the US and Spain, such as:

- Seven Sisters (Moscow), seven Soviet-era skyscrapers in Moscow, Russia

- Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, Poland

- Tower of the university's library on the Ladeuzeplein in Leuven, Belgium

References

- Symington, Andy (2003). Seville. ISBN 9781903471869.

- K., Bennison, Amira (2016). The Almoravid and Almohad empires. Edinburgh. ISBN 9780748646814. OCLC 957145068.

- Rosser-Owen, Mariam. "Andalusi Spolia in Medieval Morocco : "Architectural Politics, Political Architecture." Medieval Encounters, vol. 20, no. 2, Mar. 2014, pp. 152-198. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1163/15700674-12342164.

- Fromherz, Allen James (2016). The Near West : Medieval North Africa, Latin Europe and the Mediterranean in the Second Axial Age. Edinburgh. ISBN 9780748642946. OCLC 950901630.

- Corfis, Ivy A. (2010). Al-Andalus, Sepharad and Medieval Iberia : Cultural Contact and Diffusion. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 14. ISBN 978-90-47-44154-0.

- RUIZ, BEGOÑA ALONSO, and ALFONSO JIMÉNEZ MARTÍN. “A Fifteenth-Century Plan of the Cathedral of Seville.” Architectural History, vol. 55, 2012, pp. 57–77. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43489715.

- The mosque : history, architectural development & regional diversity. Frishman, Martin., Khan, Hasan-Uddin., Al-Asad, Mohammad. London: Thames & Hudson. 2002. ISBN 0500283451. OCLC 630140824.CS1 maint: others (link)

- https://labelleseville.com/tours-seville/Informes_de_la_Construcci%C3%B3n_Vol_49_452.pdf | PDF INFORMES PUBLICO GIRALDA

Other photos

View from the bottom.

View from the bottom. Giralda by night.

Giralda by night. The statue of the Giraldillo.

The statue of the Giraldillo. The Giralda at its various stages of construction: Almohad (left), Medieval Christian (right), and Renaissance (center).

The Giralda at its various stages of construction: Almohad (left), Medieval Christian (right), and Renaissance (center). Fountain in front of the Giralda.

Fountain in front of the Giralda. Giralda as seen from Patio de Banderas.

Giralda as seen from Patio de Banderas. Giralda seen from Patio de los Naranjos.

Giralda seen from Patio de los Naranjos.

External links

- Blueprints of Seville's Cathedral and Giralda, by Hernán Ruiz

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giralda. |