Minaret

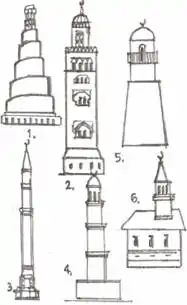

Minaret (/ˌmɪnəˈrɛt, ˈmɪnəˌrɛt/;[1] Persian: گلدسته goldasteh, Azerbaijani: minarə, Turkish: minare,[2] from Arabic: منارة manarah[2]) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets serve multiple purposes. While they provide a visual focal point, they are generally used for the Muslim call to prayer (adhan). The basic form of a minaret includes a base, shaft, a cap and head. They are generally a tall spire with a conical or onion-shaped crown.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

Functions

In the early 9th century, the first minarets were placed opposite the qibla wall.[3] Oftentimes, this placement was not beneficial in reaching the community for the call to prayer.[3] They served as a reminder that the region was Islamic and helped to distinguish mosques from the surrounding architecture.[4]

In addition to providing a visual cue to a Muslim community, the other function is to provide a vantage point from which the call to prayer, or adhan, is made. The call to prayer is issued five times each day: dawn, noon, mid-afternoon, sunset, and night.[5] In most modern mosques, the adhān is called from the musallah (prayer hall) via microphone to a speaker system on the minaret.[5]

Construction

The basic form of minarets consists of four parts: a base, a shaft, a cap and a head. Minarets may be conical (tapering), square, cylindrical, or polygonal (faceted). Stairs circle the shaft in a counter-clockwise fashion, providing necessary structural support to the highly elongated shaft.[6] The gallery is a balcony that encircles the upper sections from which the muezzin may give the call to prayer.[7] It is covered by a roof-like canopy and adorned with ornamentation, such as decorative brick and tile work, cornices, arches and inscriptions, with the transition from the shaft to the gallery typically displaying muqarnas.[7]

History

The earliest mosques lacked minarets, and the call to prayer was often performed from smaller tower structures.[3][9][10] Hadiths relay that the early Muslim community of Medina gave the call to prayer from the roof of the house of Muhammad, which doubled as a place for prayer.[3]

Scholarly findings trace the origin of minarets to the Umayyad Caliphate and explain that these minarets were a copy of church steeples found in Syria in those times. The first minarets were derived architecturally from the Syrian church tower. Other references suggest that the towers in Syria originated from ziggurats of Babylonian and Assyrian shrines of Mesopotamia.[11][12]

The first known minarets appear in the early 9th century under Abbasid rule, and were not widely used until the 11th century.[3] These early minaret forms were originally placed in the middle of the wall opposite the qibla wall.[3] These towers were built across the empire in a height to width ratio of 3:1.[3]

The oldest minaret is the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia and it is consequently the oldest minaret still standing.[3][8][13] The construction of the Great Mosque of Kairouan dates to the year 836.[3][14] The mosque is constituted by three levels of decreasing widths that reach 31.5 meters tall.[3][14]

Minarets have had various forms (in general round, squared, spiral or octagonal) in light of their architectural function.[6] Minarets are built out of any material that is readily available, and often changes from region to region.[3] The number of minarets by mosques is not fixed, originally one minaret would accompany each mosque, then the builder could construct several more.[15]

_-_TIMEA.jpg.webp)

Local styles

Central Asia

- During the Seljuk period, minarets were highly decorated with geometric and calligraphic design.[16] They were built prolifically, even at smaller mosques or mosque complexes. Additionally, minarets during the Seljuk period were characterized by their circular plans and octagonal bases.[17] The Bukhara minaret remains the most well known of the Seljuk minarets for its use of brick patterns and inscriptions.[17]

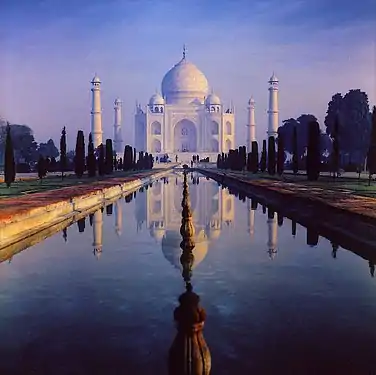

- The "international Timurid" style surfaced in central Asia during the 17th century and is categorized by the use of multiple minarets.[17] Examples of this style include the minarets on the roof of the south gate in Akbar's Tomb at Sikandra (1613), the minarets on the Tomb of Jahangir (1628-1638), as well as the four minarets surrounding the mausoleum of the Taj Mahal.[17]

- Egypt

- The styles of minarets have varied slightly throughout the history of Egypt. Most minarets were on a square base, however, the shaft could be plain or decorated and topped with various crowns and pavilions.[16] The tiers of the minaret are often separated by balconies.[16]

- The Mosque of al-Hakim, built between 990 and 1010, has a square base with a shaft that tapers towards the crown.[16]

- East China

- Eastern Chinese minarets were heavily influenced by the Islamic minarets of Iran.[17] They often had circular platforms and cylindrical shafts with decorative patterns of the Chinese landscape.[17] The Tower of Light, also known as the Guangta minaret (1350), merges aspects of Islamic and Chinese architecture.[17]

- Iraq

- The Great Mosque of Samarra (848–852) is one of the earliest minarets and is characterized by a 30-metre-high (98 ft) cylindrical tower outside the walls of the mosque.[3] A common Abbasid style of minaret, also seen in Iraq, is characterized by a structure with a polygonal base and a thick cylindrical shaft. It is also typically found on the roof of the mosque.[17]

.jpg.webp) The Great Mosque of Samarra has a unique spiral minaret.

The Great Mosque of Samarra has a unique spiral minaret. - Two examples of this style are the Mosque of al-Khaffafin and the Mosque of Qumriyya.

- Iran

- The minarets of 12th century Iran often had cylindrical shafts with square or octagonal bases that taper towards their capitals. These minarets became the most common style across the Islamic world. These forms were also highly decorated. Pairs of minaret towers that flank the mosque entrance originate from Iran.[16]

- Southeast Asia

- Tower minarets were not as common in Southeast Asia as mosques were designed to function more as community structures. Mosques were designed to be much smaller and occasionally contained staircase minarets.[17]

- Tunisia

- The minaret at the Great Mosque of Kairouan, built in 836, influenced all other minarets in the Islamic west.[3] It is the oldest minaret in the Muslim world.

- Turkey

- The Seljuks of Rum, a successor state of the Seljuks, built paired portal minarets from brick that had Iranian origins.[16]

- In general, minarets in Anatolia were singular and received decorative emphasis while the mosque remained plain.[16] The minarets were used at the corners of mosques, as seen in the Divrigi Great Mosque.

.jpg.webp) The Süleymaniye Mosque in Turkey has minarets reaching 70 meters.

The Süleymaniye Mosque in Turkey has minarets reaching 70 meters. - The Ottoman empire continued the Iranian tradition of cylindrical tapering minaret forms with a square base.[16] Minarets were often topped with crescent moon symbols.[16] Use of more than one minaret, and larger minarets, was used to show patronage.[16]

- For example, the Suleymaniye Dome has minarets reaching 70 meters.

- West Africa

- West African minarets are characterized by glazed ceramics that allowed the structures to take on new monumental forms.[17] Typically, they are a single, square minaret with battered walls. Notable exceptions include a few octagonal minarets in northern cities - Chefchaouen, Tetouan, Rabat, Ouezzane, Asilah, and Tangier - and the round minaret of Moulay Idriss.

See also

References

- "minaret". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- "minaret." Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. 21 Mar. 2009.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2013). The minaret. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748637257. OCLC 856037134.

- Weisbin, Kendra. "Introduction to mosque architecture". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- "Mosque | place of worship". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Gamm, Niki (March 9, 2013). "How to build a minaret". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Doğangün, Adem; İskender Tuluk, Ö; Livaoğlu, Ramazan; Acar, Ramazan. (May 2002). "Traditional Turkish minarets on the basis of architectural and engineering concepts". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam, Language and Meaning: Commemorative Edition. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 128

- Donald Hawley, Oman, pg. 201. Jubilee edition. Kensington: Stacey International, 1995. ISBN 0905743636

- Creswell, K. A. C. (March 1926). "The Evolution of the Minaret, with Special Reference to Egypt-I". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 48 (276). doi:10.2307/862832. JSTOR 862832.

- Creswell, K. A. C. (March 1926). "The Evolution of the Minaret, with Special Reference to Egypt". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 48.

- Bloom, Jonathan (1989). Minaret Symbol of Islam. University of Oxford. ISBN 0197280137.

- Linda Kay Davidson and David Martin Gitlitz, Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2002. p. 302

- "Minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara Mediterranean Heritage)". Archived from the original on 2013-05-11.

- "Minaret | architecture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Fraenkel, J.; Sadan, J. (April 24, 2012). "Manār, Manāra". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru (2017). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 9781119068570. OCLC 963439648.

Further reading

- Jonathan M. Bloom (1989), Minaret, symbol of Islam, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-728013-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minarets. |