Great conjunction

A great conjunction is a conjunction of the planets Jupiter and Saturn, when the two planets appear closest together in the sky. Great conjunctions occur approximately every 20 years when Jupiter "overtakes" Saturn in its orbit. They are named "great" for being by far the rarest of the conjunctions between naked-eye planets[1] (i.e. excluding Uranus and Neptune).

The spacing between the planets varies from conjunction to conjunction with most events being 0.5 to 1.3 degrees (30 to 78 arcminutes, or 1 to 2.5 times the width of a full moon). Very close conjunctions happen much less frequently (though the maximum of 1.3° is still close by inner planet standards): separations of less than 10 arcminutes have only happened four times since 1200, most recently in 2020.[2]

In history

Great conjunctions attracted considerable attention in the past as omens. During the late Middle Ages and Renaissance they were a topic broached by the pre-scientific and transitional astronomer-astrologers of the period up to the time of Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, by scholastic thinkers such as Roger Bacon[3] and Pierre d'Ailly,[4] and they are mentioned in popular and literary works by authors such as Dante[5] and Shakespeare.[6] This interest is traced back in Europe to translations of Arabic texts especially Albumasar's book on conjunctions.[7]

Despite mathematical errors and some disagreement among astrologers about when trigons began, belief in the significance of such events generated a stream of publications that grew steadily until the end of the 16th century. As the great conjunction of 1583 was last in the water trigon it was widely supposed to herald apocalyptic changes; a papal bull against divination was issued in 1586 but as nothing significant happened by the feared event of 1603, public interest rapidly died. By the start of the next trigon, modern scientific consensus had long-established astrology as pseudoscience, and planetary alignments were no longer perceived as omens.[8]

Celestial mechanics

On average, great conjunction seasons occur once every 19.859 Julian years (each of which is 365.25 days). This number can be calculated by the synodic period formula

in which J and S are the orbital periods of Jupiter (4332.59 days) and Saturn (10759.22 days), respectively.[2] (In practice, Earth's orbit size can cause great conjunctions to reoccur up to some months away from the average time or the time they happen on the Sun.) Since the equivalent periods of other naked-eye planet pairs are all under 27 months, this makes great conjunctions the rarest.

Occasionally there is more than one great conjunction in a season, which happens whenever they're close enough to opposition: this is called a triple conjunction (which is not exclusive to great conjunctions). In this scenario, Jupiter and Saturn will occupy the same right ascension on three occasions or same ecliptic longitude on three occasions, depending on which definition of "conjunction" one uses (this is due to apparent retrograde motion and happens within months). The most recent triple conjunction occurred in 1980–81[9] and the next will be in 2238–39.

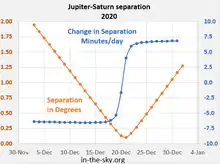

The most recent great conjunction occurred on 21 December 2020, and the next will occur on 4 November 2040. During the 2020 great conjunction, the two planets were separated in the sky by 6 arcminutes at their closest point, which was the closest distance between the two planets since 1623.[10] The closeness is the result of the conjunction occurring in the vicinity of one of the two longitudes where the two orbits appear to intersect when viewed from the Sun (which has a point of view similar to Earth).

Because 19.859 years is equal to 1.674 Jupiter orbits and 0.674 Saturn orbits, three of these periods come close to a whole number of revolutions. This is why the longitude cycle, as shown in the diagram to the right, has a triangular pattern. The three points of the triangle revolve in the same direction as the planets at the rate of approximately one-sixth of a revolution per four centuries thus creating especially close conjunctions on an approximately four-century cycle. Currently the longitudes of close great conjunctions are about 307.4 and 127.4 degrees, in the constellations Capricornus and Cancer respectively. The position of Earth in its orbit, however, can make the planets appear up to about 10 degrees ahead of or behind their heliocentric longitude.[2]

Saturn's orbit plane is inclined 2.485 degrees relative to Earth's, and Jupiter's is inclined 1.303 degrees. The ascending nodes of both planets are similar (100.6 degrees for Jupiter and 113.7 degrees for Saturn), meaning if Saturn is above or below Earth's orbital plane Jupiter usually is too. Because these nodes align so well it would be expected that no closest approach will ever be much worse than the difference between the two inclinations. Indeed, between year 1 and 3000, the maximum conjunction distances were 1.3 degrees in 1306 and 1940. Conjunctions in both years occurred when the planets were tilted most out of the plane: longitude 206 degrees (therefore above the plane) in 1306, and longitude 39 degrees (therefore below the plane) in 1940.[2]

List of great conjunctions (1200 to 2400)

The following table[2] details great conjunctions in between 1200 and 2400. The dates are given for the conjunctions in right ascension (the dates for conjunctions in ecliptic longitude can differ by several days). Dates before 1582 are in the Julian calendar while dates after 1582 are in the Gregorian calendar.

Longitude is measured counterclockwise from the location of the First Point of Aries (the location of the March equinox) at epoch J2000. This non-rotating coordinate system doesn't move with the precession of Earth's axes, thus being suited for calculations of the locations of stars. (In astrometry latitude and longitude are based on the ecliptic which is Earth's orbit extended sunward and anti-sunward indefinitely.) The other common conjunction coordinate system is measured counterclockwise in right ascension from the First Point of Aries and is based on Earth's equator and the meridian of the equinox point both extended upwards indefinitely; ecliptic separations are usually smaller.

Distance is the angular separation between the planets in sixtieths of a degree (minutes of arc) and elongation is the angular distance from the Sun in degrees. An elongation between around −20 and +20 degrees indicates that the Sun is close enough to the conjunction to make it difficult or impossible to see, sometimes more difficult at some geographic latitudes and less difficult elsewhere. Note that the exact moment of conjunction cannot be seen everywhere as it is below the horizon or it is daytime in some places, but a place on Earth affects minimum separation less than it would if an inner planet was involved. Negative elongations indicate the planet is west of the Sun (visible in the morning sky), whereas positive elongations indicate the planet is east of the Sun (visible in the evening sky).

The great conjunction series is roughly analogous to the Saros series for solar eclipses (which are Sun–Moon conjunctions). Conjunctions in a particular series occur about 119.16 years apart. The reason it is every six conjunctions instead of every three is that 119.16 years is closer to a whole number of years than 119.16/2 = 59.58 is, so Earth will be closer to the same position in its orbit and conjunctions will appear more similar. All series will have progressions where conjunctions gradually shift from only visible before sunrise to visible throughout the night to only visible after sunset and finally back to the morning sky again. The location in the sky of each conjunction in a series should increase in longitude by 16.3 degrees on average, making one full cycle relative to the stars on average once every 2,634 years. If instead we use the convention of measuring longitude eastward from the First Point of Aries, we have to keep in mind that the equinox circulates once every c. 25,772 years, so longitudes measured that way increase slightly faster and those numbers become 17.95 degrees and 2,390 years.

A conjunction can be a member of a triple conjunction. In a triple conjunction, the series does not advance by one each event as the constellation and year is the same or close to it, this is the only time great conjunctions can be less than about 20 years apart.[2]

| Date | Longitude (degrees) | Distance (arcminutes) | Elongation (degrees) | Series | Easy to see | Triple |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 April 1206 | 66.8 | 65.3 | +23.0 | 2 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 4 March 1226 | 313.8 | 2.1 | −48.6 | 3 | Yes | No |

| 21 September 1246 | 209.6 | 62.3 | +13.5 | 4 | No | No |

| 23 July 1265 | 79.9 | 57.3 | −58.5 | 5 | Yes | No |

| 31 December 1285 | 318.0 | 10.6 | +19.8 | 6 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 24 December 1305 | 220.4 | 71.5 | −70.0 | 1 | Yes | Yes |

| 20 April 1306 | 217.8 | 75.5 | +170.7 | 1 | Yes | |

| 19 July 1306 | 215.7 | 78.6 | +82.5 | 1 | Yes | |

| 1 June 1325 | 87.2 | 49.2 | −0.4 | 2 | No | No |

| 24 March 1345 | 328.2 | 21.2 | −52.5 | 3 | Yes | No |

| 25 October 1365 | 226.0 | 72.6 | −3.7 | 4 | No | No |

| 8 April 1385 | 94.4 | 43.2 | +58.8 | 5 | Yes | No |

| 16 January 1405 | 332.1 | 29.3 | +18.1 | 6 | No | No |

| 10 February 1425 | 235.2 | 70.7 | +104.1 | 1 | Yes | Yes |

| 10 March 1425 | 234.4 | 72.4 | −141.6 | 1 | Yes | |

| 24 August 1425 | 230.6 | 76.3 | +62.6 | 1 | Yes | |

| 13 July 1444 | 106.9 | 28.5 | −15.9 | 2 | No | No |

| 7 April 1464 | 342.1 | 38.2 | −52.6 | 3 | Yes | No |

| 17 November 1484 | 240.2 | 68.3 | −12.3 | 4 | No | No |

| 25 May 1504 | 113.4 | 18.7 | +33.5 | 5 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 30 January 1524 | 345.8 | 46.1 | +19.1 | 6 | No | No |

| 17 September 1544 | 245.1 | 69.2 | +53.4 | 1 | Yes | No |

| 25 August 1563 | 125.3 | 6.8 | −42.1 | 2 | Yes | No |

| 2 May 1583 | 355.9 | 52.9 | −51.2 | 3 | Yes | No |

| 17 December 1603 | 253.8 | 59.0 | −17.6 | 4 | No | No |

| 17 July 1623 | 131.9 | 5.2 | +12.9 | 5 | No | No |

| 24 February 1643 | 0.1 | 59.3 | +18.8 | 6 | No | No |

| 17 October 1663 | 254.8 | 59.2 | +48.7 | 1 | Yes | No |

| 23 October 1682 | 143.5 | 15.4 | −71.8 | 2 | Yes | Yes |

| 8 February 1683 | 141.1 | 11.6 | +175.8 | 2 | Yes | |

| 17 May 1683 | 138.9 | 15.8 | +77.5 | 2 | Yes | |

| 21 May 1702 | 10.8 | 63.4 | −53.5 | 3 | Yes | No |

| 5 January 1723 | 265.1 | 47.7 | −23.8 | 4 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 30 August 1742 | 150.8 | 27.8 | −10.3 | 5 | No | No |

| 18 March 1762 | 15.6 | 69.4 | +14.5 | 6 | No | No |

| 5 November 1782 | 271.1 | 44.6 | +44.9 | 1 | Yes | No |

| 16 July 1802 | 157.7 | 39.5 | +41.3 | 2 | Yes | No |

| 18 June 1821 | 27.1 | 72.9 | −62.9 | 3 | Yes | No |

| 26 January 1842 | 281.1 | 32.3 | −27.1 | 4 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 20 October 1861 | 170.2 | 47.4 | −39.5 | 5 | Yes | No |

| 17 April 1881 | 33.0 | 74.5 | +3.8 | 6 | No | No |

| 28 November 1901 | 285.4 | 26.5 | +38.3 | 1 | Yes | No |

| 8 September 1921 | 177.3 | 58.3 | +11.1 | 2 | No | No |

| 6 August 1940 | 45.2 | 71.4 | −89.8 | 3 | Yes | Yes |

| 21 October 1940 | 41.1 | 74.1 | −165.7 | 3 | Yes | |

| 14 February 1941 | 39.9 | 77.4 | +73.3 | 3 | Yes | |

| 18 February 1961 | 295.7 | 13.8 | −34.5 | 4 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 1 January 1981 | 189.8 | 63.7 | −91.4 | 5 | Yes | Yes |

| 6 March 1981 | 188.3 | 63.3 | −155.9 | 5 | Yes | |

| 25 July 1981 | 185.3 | 67.6 | +62.7 | 5 | Yes | |

| 28 May 2000 | 52.6 | 68.9 | −14.6 | 6 | No | No |

| 21 December 2020 | 300.3 | 6.1 | +30.2 | 1 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 4 November 2040 | 197.8 | 72.8 | −24.6 | 2 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 8 April 2060 | 59.6 | 67.5 | +41.7 | 3 | Yes | No |

| 15 March 2080 | 310.8 | 6.0 | −43.7 | 4 | Yes | No |

| 18 September 2100 | 204.1 | 62.5 | +29.5 | 5 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 15 July 2119 | +73.2 | 57.5 | −37.8 | 6 | Yes | No |

| 14 January 2140 | 315.1 | 14.5 | +22.7 | 1 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 20 February 2159 | 215.3 | 71.2 | −50.3 | 2 | Yes | No |

| 28 May 2179 | 80.6 | 49.5 | +16.1 | 3 | No | No |

| 8 April 2199 | 325.6 | 25.2 | −50.0 | 4 | Yes | No |

| 1 November 2219 | 221.7 | 63.1 | +6.8 | 5 | No | No |

| 6 September 2238 | 93.2 | 39.3 | −67.6 | 6 | Yes | Yes |

| 12 January 2239 | 90.2 | 47.5 | +161.3 | 6 | Yes | |

| 22 March 2239 | 88.4 | 45.3 | +89.9 | 6 | Yes | |

| 2 February 2259 | 329.6 | 33.3 | +19.6 | 1 | Depends on observer latitude | No |

| 5 February 2279 | 231.9 | 69.9 | −80.3 | 2 | Yes | Yes |

| 7 May 2279 | 229.9 | 73.8 | −172.6 | 2 | Yes | |

| 31 August 2279 | 227.2 | 74.9 | +73.3 | 2 | Yes | |

| 12 July 2298 | 100.6 | 28.3 | −6.0 | 3 | No | No |

| 26 April 2318 | 339.8 | 41.8 | −51.8 | 4 | Yes | No |

| 1 December 2338 | 237.3 | 66.3 | −7.4 | 5 | No | No |

| 22 May 2358 | 107.5 | 18.5 | +50.7 | 6 | Yes | No |

| 18 February 2378 | 343.7 | 50.5 | +19.4 | 1 | No | No |

| 2 October 2398 | 240.7 | 65.9 | +58.2 | 2 | Yes | No |

|

|

Notable great conjunctions

| Date | Ecliptic coordinates (non-rotating/star tracking) | Separation (in arcminutes) | Visibility Note: There is always at least a small area around one or both poles that cannot see due to midnight sun or midnight twilight; this is not mentioned when the conjunction is easily visible from most of each hemisphere | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 March 1793 BC | 153.4° | 1.3 | Evening | The closest conjunction between prehistoric times and the 46th century AD. Part of triple conjunction. |

| 28 December 424 BC | 322.8° | 1.5 | Evening, hard to see. | |

| 6 March 372 | 316.6° | 1.9 | Morning | The closest conjunction of the first three millennia AD. |

| 31 December 431 | 320.6° | 6.2 | Evening, hard to see. | |

| 13 September 709 | 130.8° | 8.3 | Morning, part of a triple conjunction. | |

| 22 July 769 | 137.8° | 4.3 | Too close to the Sun to be visible. | |

| 11 December 1166 | 303.3° | 2.1 | Evening, hard to see. | |

| 4 March 1226 | 313.8° | 2.1 | Morning | |

| 25 August 1563 | 125.3° | 6.8 | Morning | |

| 16 July 1623 | 131.9° | 5.2 | Evening, hard to see (especially from Northern Hemisphere). | |

| 21 December 2020 | 300.3° | 6.1 | Evening, hard to see from high northern latitudes, not visible in Antarctic (poor angle, summer sun). | 303+ degree heliocentric longitude close to the ideal 317 degree orbit plane intersection longitude for closeness (J2000) |

| 15 March 2080 | 310.8° | 6.0 | Morning, hard to see from mid and high northern latitudes | |

| 24 August 2417 | 119.6° | 5.4 | Morning, not easy to impossible to see from parts of the Southern Hemisphere and Arctic. | |

| 6 July 2477 | 126.2° | 6.3 | Evening, easier to see in the Southern Hemisphere. | |

| 25 December 2874 | 297.1° | 2.3 | Evening, summer sun hinders viewing in Antarctica. | |

| 19 March 2934 | 307.6° | 9.3 | Morning | |

| 8 March 4523 | 287.8° | 1.0 | Morning, not easy to impossible to see from high northern latitudes and the South Pole area due to a low height above the horizon and/or midnight sun or "midnight twilight". | The closest conjunction in almost 14,400 years.[2] |

| Longitude (from Earth) | Number of conjunctions |

|---|---|

| 119 to 138 degrees | 6 |

| 297 to 321 degrees | 8 |

| Other | 0 |

7 BC

When studying the great conjunction of 1603, Johannes Kepler thought that the Star of Bethlehem might have been the occurrence of a great conjunction. He calculated that a triple conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn occurred in 7 BC (−6 using astronomical year numbering);[11][12]

1563

The astronomers from the Cracow Academy (Jan Muscenius, Stanisław Jakobejusz, Nicolaus Schadeck, Petrus Probosczowicze, and others) observed the great conjunction of 1563 to compare Alfonsine tables (based on a geocentric model) with the Prutenic Tables (based on Copernican heliocentrism). In the Prutenic Tables the astronomers found Jupiter and Saturn so close to each other that Jupiter covered Saturn[13] (actual angular separation was 6.8 minutes on 25 August 1563[2]). The Alfonsine tables suggested that the conjunction should be observed on another day but on the day indicated by the Alfonsine tables the angular separation was a full 141 minutes. The Cracow professors suggested following the more accurate Copernican predictions and between 1578 and 1580 Copernican heliocentrism was lectured on three times by Valentin Fontani.[13]

2020

The great conjunction of 2020 was the closest since 1623[10][2] and eighth closest of the first three millennia AD, with a minimum separation between the two planets of 6.1 arcminutes.[2] This great conjunction was also the most easily visible close conjunction since 1226 (as the previous close conjunctions in 1563 and 1623 were closer to the Sun and therefore more difficult to see).[14] It occurred seven weeks after the heliocentric conjunction, when Jupiter and Saturn shared the same heliocentric longitude.[15]

The closest separation occurred on 21 December at 18:20 UTC,[9] when Jupiter was 0.1° south of Saturn and 30° east of the Sun. This meant both planets appeared together in the field of view of most small- and medium-sized telescopes (though they were distinguishable from each other without optical aid).[16] During the closest approach, both planets appeared to be a binary object to the naked eye.[14] From mid-northern latitudes, the planets were visible one hour after sunset at less than 15° in altitude above the southwestern horizon in the constellation of Capricornus.[17][18]

The conjunction attracted considerable media attention, with news sources calling it the "Christmas Star" due to the proximity of the date of the conjunction to Christmas, and for a great conjunction being one of the hypothesized explanations for the biblical Star of Bethlehem.[19]

Gallery

Photograph taken two days before closest approach with a separation of approximately 15 arcminutes.

Photograph taken two days before closest approach with a separation of approximately 15 arcminutes. Great conjunction photographed on December 19, 2020, with a 360 mm (14 in) SCT telescope and color CCD.

Great conjunction photographed on December 19, 2020, with a 360 mm (14 in) SCT telescope and color CCD. Simulated best-case scenario view through a telescope.

Simulated best-case scenario view through a telescope. Video created using photographs of the event taken over a span of 90 days.[20]

Video created using photographs of the event taken over a span of 90 days.[20] Photograph of the great conjunction of 2020 taken two days before closest approach with the four Galilean moons visible around Jupiter. (Titan can also be seen to the right of Saturn.)

Photograph of the great conjunction of 2020 taken two days before closest approach with the four Galilean moons visible around Jupiter. (Titan can also be seen to the right of Saturn.) December 21, 2020, Jupiter and Saturn, 130mm Bresser Messier

December 21, 2020, Jupiter and Saturn, 130mm Bresser Messier Photograph depicting the great conjunction, taken from Syracuse, Italy.

Photograph depicting the great conjunction, taken from Syracuse, Italy. Photograph of Jupiter and Saturn with the Moon on 16 December 2020

Photograph of Jupiter and Saturn with the Moon on 16 December 2020

7541

As well as being a triple conjunction, the great conjunction of 7541 is expected to feature two occultations: one partial on 16 February, and one total on 17 June.[9] However, the accuracy of planetary positions this far into the future is highly uncertain, so some calculations of planetary positions predict very close conjunctions in 7541 instead of occultations. This will be the first occultation between the two planets since 6857 BC; superimposition requires a separation of less than approximately 0.4 arcminutes.[2]

See also

References

- Ford, Dominic (20 October 2020). "Great Conjunction". In The Sky. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Jupiter-Saturn Conjunction Series". sparky.rice.edu.

- The Opus Majus of Roger Bacon, ed. J. H. Bridges, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1897, Vol. I, p. 263.

- De Concordia astronomice Veritatis et narrations historic (1414)

- Woody, K. M. (1977). "Dante and the Doctrine of the Great Conjunctions". Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society. 95: 119–134. JSTOR 40166243.

- Aston, Margaret (1970). "The Fiery Trigon Conjunction: An Elizabethan Astrological Prediction". Isis. 61 (2): 159–187. doi:10.1086/350618.

- De magnis coniunctionibus was translated in the 12th century, a modern edition-translation by K. Yamamoto and Ch. Burnett, Leiden, 2000

- Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford University Press, 1971) p. 414-415, ISBN 9780195213607

- Jones, Graham. "The December 2020 Great Conjunction". timeanddate.com. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Hunt, Jeffrey L. (20 February 2020). "1623: The Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn". When the Curves Line Up. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Burke-Gaffney, W. (1937). "Kepler and the Star of Bethlehem". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 31: 417. Bibcode:1937JRASC..31..417B. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Molnar, Michael R. (1999). The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi. Rutgers University Press.

- Kesten, Hermann (1945). Copernicus and his World. New York: Roy Publishers. p. 320.

- Jacob Dickey (6 December 2020). "Witness the Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn on December 21st". WCIA. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Hunt, Jeffrey L. (11 September 2020). "2020, November 2: Jupiter – Saturn Heliocentric Conjunction". When the Curves Line Up. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "2020: December 21: The Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn". When the Curves Line Up. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Hunt, Jeffrey L. (11 December 2019). "2020: December 21: The Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn". When the Curves Line Up. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "5 upcoming conjunctions visible in the night sky, and how to see them". Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Clark, Stuart (14 December 2020). "Starwatch: 'Christmas star' is the closest great conjunction in almost 400 years" – via www.theguardian.com.

- How I Made a 3 Month long Time-lapse Of The 2020 Great Conjunction. Cody'sLab. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |