Star of Bethlehem

The Star of Bethlehem, or Christmas Star,[1] appears in the nativity story of the Gospel of Matthew where "wise men from the East" (Magi) are inspired by the star to travel to Jerusalem. There, they meet King Herod of Judea, and ask him:

Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we have seen His star in the East and have come to worship Him.[2]

Herod calls together his scribes and priests who, quoting a verse from the Book of Micah, interpret it as a prophecy that the Jewish Messiah would be born in Bethlehem to the south of Jerusalem. Secretly intending to find and kill the Messiah in order to preserve his own kingship, Herod invites the wise men to return to him on their way home.

The star leads them to Jesus' Bethlehem birthplace, where they worship him and give him gifts. The wise men are then given a divine warning not to return to Herod, so they return home by a different route.[3]

Many Christians believe the star was a miraculous sign. Some theologians claimed that the star fulfilled a prophecy, known as the Star Prophecy.[4] Astronomers have made several attempts to link the star to unusual celestial events, such as a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn or Jupiter and Venus,[5] a comet, or a supernova.[6]

Some modern scholars do not consider the story to be describing a historical event but a pious fiction created by the author of the Gospel of Matthew.[7]

The subject is a favorite at planetarium shows during the Christmas season.[8] However, most ancient sources and Church tradition generally indicate that the wise men visited Bethlehem sometime after Jesus’ birth.[9] The visit is traditionally celebrated on Epiphany (January 6) in western Christianity.[10]

Matthew's account describes Jesus with the broader Greek word παιδίον (paidion), which can mean either "infant" or "child" rather than the more specific word for infant, βρέφος (bréphos). This possibly implies that some time has passed since the birth. However, the word παιδίον (paidíon) is also used in Luke's Gospel specifically concerning Jesus’ birth and his later presentation at the temple.[11] Herod I has all male Hebrew babies in the area up to age two killed in the Massacre of the Innocents.

Matthew's narrative

The Gospel of Matthew tells how the Magi (often translated as "wise men", but more accurately astrologers)[12] arrive at the court of Herod in Jerusalem and tell the king of a star which signifies the birth of the King of the Jews:

Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, saying, 2 “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the East, and have come to worship him.” 3 When Herod the king heard this, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him; 4 and assembling all the chief priests and scribes of the people, he inquired of them where the Christ was to be born. 5 They told him, “In Bethlehem of Judea; for so it is written by the prophet:

6 ‘And you, O Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who will govern my people Israel.’”

7 Then Herod summoned the wise men secretly and ascertained from them what time the star appeared; 8 and he sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search diligently for the child, and when you have found him bring me word, that I too may come and worship him.” 9 When they had heard the king they went their way; and lo, the star which they had seen in the East went before them, till it came to rest over the place where the child was. 10 When they saw the star, they rejoiced exceedingly with great joy; 11 and going into the house they saw the child with Mary his mother, and they fell down and worshiped him. Then, opening their treasures, they offered him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh.[13]

Herod is "troubled", not because of the appearance of the star, but because the Magi have told him that a "king of the Jews" had been born,[14] which he understands to refer to the Messiah, a leader of the Jewish people whose coming was believed to be foretold in scripture. So he asks his advisors where the Messiah would be born.[15] They answer Bethlehem, birthplace of King David, and quote the prophet Micah.[nb 1] The king passes this information along to the Magi.[16]

In a dream, they are warned not to return to Jerusalem, so they leave for their own country by another route.[17] When Herod realizes he has been tricked, he orders the execution of all male children in Bethlehem "two years old and younger," based on the age the child could be in regard to the information the magi had given him concerning the time the star first appeared.[nb 2]

Joseph, warned in a dream, takes his family to Egypt for their safety.[18] The gospel links the escape to a verse from scripture, which it interprets as a prophecy: "Out of Egypt I called my son."[19] This was a reference to the departure of the Hebrews from Egypt under Moses, so the quote suggests that Matthew saw the life of Jesus as recapitulating the story of the Jewish people, with Judea representing Egypt and Herod standing in for pharaoh.[20]

After Herod dies, Joseph and his family return from Egypt,[21] and settle in Nazareth in Galilee.[22] This is also said to be a fulfillment of a prophecy ("He will be called a Nazorean," (NRSV) which could be attributed to Judges 13:5 regarding the birth of Samson and the Nazirite vow. The word Nazareth is related to the word netzer which means "sprout",[23] and which some Bible commentators[24] think refers to Isaiah 11:1, "There shall come forth a Rod from the stem of Jesse, And a Branch shall grow out of his roots."[25][nb 3]

Explanations

Pious fiction

Many scholars who see the gospel nativity stories as later apologetic accounts created to establish the messianic status of Jesus regard the Star of Bethlehem as a pious fiction.[26][27] Aspects of Matthew's account which have raised questions of the historical event include: Matthew is the only one of the four gospels which mentions either the Star of Bethlehem or the Magi. Scholars suggest that Jesus was born in Nazareth and that the Bethlehem nativity narratives reflect a desire by the Gospel writers to present his birth as the fulfillment of prophecy.[28]

The Matthew account conflicts with that given in the Gospel of Luke, in which the family of Jesus already lives in Nazareth, travel to Bethlehem for the census, and return home almost immediately.[29]

Matthew's description of the miracles and portents attending the birth of Jesus can be compared to stories concerning the birth of Augustus (63 BC).[nb 4] Linking a birth to the first appearance of a star was consistent with a popular belief that each person's life was linked to a particular star.[30] Magi and astronomical events were linked in the public mind by the visit to Rome of a delegation of magi at the time of a spectacular appearance of Halley's Comet in AD 66[31] led by King Tiridates of Armenia, who came seeking confirmation of his title from Emperor Nero. Ancient historian Dio Cassius wrote that, "The King did not return by the route he had followed in coming,"[31] a line similar to the text of Matthew's account, but written some time after the completion of Matthew's gospel.[32]

Fulfillment of prophecy

The ancients believed that astronomical phenomena were connected to terrestrial events – As Above, So Below. Miracles were routinely associated with the birth of important people, including the Hebrew patriarchs, as well as Greek and Roman heroes.[33]

The Star of Bethlehem is traditionally linked to the Star Prophecy in the Book of Numbers:

I see him, but not now;

I behold him, but not near;

A Star shall come out of Jacob;

A Scepter shall rise out of Israel,

And batter the brow of Moab,

And destroy all the sons of tumult.[34]

Although possibly intended to refer to a time that was long past, since the kingdom of Moab had long ceased to exist by the time the Gospels were being written, this passage had become widely seen as a reference to the coming of a Messiah.[4] It was, for example, cited by Josephus, who believed it referred to Emperor Vespasian.[35] Origen, one of the most influential early Christian theologians, connected this prophecy with the Star of Bethlehem:

If, then, at the commencement of new dynasties, or on the occasion of other important events, there arises a comet so called, or any similar celestial body, why should it be matter of wonder that at the birth of Him who was to introduce a new doctrine to the human race, and to make known His teaching not only to Jews, but also to Greeks, and to many of the barbarous nations besides, a star should have arisen? Now I would say, that with respect to comets there is no prophecy in circulation to the effect that such and such a comet was to arise in connection with a particular kingdom or a particular time; but with respect to the appearance of a star at the birth of Jesus there is a prophecy of Balaam recorded by Moses to this effect: There shall arise a star out of Jacob, and a man shall rise up out of Israel.[36]

Origen suggested that the Magi may have decided to travel to Jerusalem when they "conjectured that the man whose appearance had been foretold along with that of the star, had actually come into the world".[37]

The Magi are sometimes called "kings" because of the belief that they fulfill prophecies in Isaiah and Psalms concerning a journey to Jerusalem by gentile kings.[38] Isaiah mentions gifts of gold and incense.[39] In the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament probably used by Matthew, these gifts are given as gold and frankincense,[40] similar to Matthew's "gold, frankincense, and myrrh."[41] The gift of myrrh symbolizes mortality, according to Origen.[37]

While Origen argued for a naturalistic explanation, John Chrysostom viewed the star as purely miraculous: "How then, tell me, did the star point out a spot so confined, just the space of a manger and shed, unless it left that height and came down, and stood over the very head of the young child? And at this the evangelist was hinting when he said, "Lo, the star went before them, till it came and stood over where the young Child was."[42]

Astronomical object

Although magi (Greek μαγοι) is usually translated as "wise men," in this context it probably means 'astronomer'/'astrologer'.[43] The involvement of astrologers in the story of the birth of Jesus was problematic for the early Church, because they condemned astrology as demonic; a widely cited explanation was that of Tertullian, who suggested that astrology was allowed 'only until the time of the Gospel'.[44]

Planetary conjunction

In 1614, German astronomer Johannes Kepler determined that a series of three conjunctions of the planets Jupiter and Saturn occurred in the year 7 BC.[8] He argued (incorrectly) that a planetary conjunction could create a nova, which he linked to the Star of Bethlehem.[8] Modern calculations show that there was a gap of nearly a degree (approximately twice a diameter of the moon) between the planets, so these conjunctions were not visually impressive.[45] An ancient almanac has been found in Babylon which covers the events of this period, but does not indicate that the conjunctions were of any special interest.[45] In the 20th century, Professor Karlis Kaufmanis, an astronomer, argued that this was an astronomical event where Jupiter and Saturn were in a triple conjunction in the constellation Pisces.[46][47] Archaeologist and Assyriologist Simo Parpola has also suggested this explanation.[48]

In 6 BC, there were conjunctions/occultations (eclipses) of Jupiter by the Moon in Aries. "Jupiter was the regal 'star' that conferred kingships – a power that was amplified when Jupiter was in close conjunctions with the Moon. The second occultation on April 17 coincided precisely when Jupiter was 'in the east', a condition mentioned twice in the biblical account about the Star of Bethlehem."[49]

In 3–2 BC, there was a series of seven conjunctions, including three between Jupiter and Regulus and a strikingly close conjunction between Jupiter and Venus near Regulus on June 17, 2 BC. "The fusion of two planets would have been a rare and awe-inspiring event", according to Roger Sinnott.[50] Another Venus–Jupiter conjunction occurred earlier in August, 3 BC.[51] However, these events occurred after the generally accepted date of 4 BC for the death of Herod. Since the conjunction would have been seen in the west at sunset it could not have led the magi south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem.[52]

Double occultation on Saturday (Sabbath) April 17, 6 BC

Astronomer Michael R. Molnar argues that the "star in the east" refers to an astronomical event with astrological significance in the context of ancient Greek astrology.[53] He suggests a link between the Star of Bethlehem and a double occultation of Jupiter by the moon on March 20 and April 17 of 6 BC in Aries, particularly the second occultation on April 17.[54][55] Occultations of planets by the moon are quite common, but Firmicus Maternus, an astrologer to Roman Emperor Constantine, wrote that an occultation of Jupiter in Aries was a sign of the birth of a divine king.[54][56] He argues that Aries rather than Pisces was the zodiac symbol for Judea, a fact that would affect previous interpretations of astrological material. Molnar's theory was debated by scientists, theologians, and historians during a colloquium on the Star of Bethlehem at the Netherlands’ University of Groningen in October 2014. Harvard astronomer Owen Gingerich supports Molnar's explanation but noted technical questions.[57] "The gospel story is one in which King Herod was taken by surprise," said Gingerich. "So it wasn’t that there was suddenly a brilliant new star sitting there that anybody could have seen [but] something more subtle."[57] Astronomer David A. Weintraub says, "If Matthew’s wise men actually undertook a journey to search for a newborn king, the bright star didn’t guide them; it only told them when to set out."[53]

There is an explanation given that the events were quite close to the sun and would not have been visible to the naked eye.[58]

Regulus, Jupiter, and Venus

Attorney Frederick Larson examined the biblical account in the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 2[59] and found the following nine qualities of Bethlehem's Star:[60][61] It signified birth, it signified kingship, it was related to the Jewish nation, and it rose "in the East";[62] King Herod had not been aware of it;[63] it appeared at an exact time;[64] it endured over time;[65] and, according to Matthew,[66] it was in front of the Magi when they traveled south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, and then stopped over Bethlehem.[67]

Using the Starry Night astronomy software, and an article[68] written by astronomer Craig Chester[69] based on the work of archeologist and historian Ernest Martin,[70][71] Larson thinks all nine characteristics of the Star of Bethlehem are found in events that took place in the skies of 3–2 BC.[61][72] Highlights[73] include a triple conjunction of Jupiter, called the king planet, with the fixed star Regulus, called the king star, starting in September 3 BC.[74][75] Larson believes that may be the time of Jesus' conception.[72]

By June of 2 BC, nine months later, the human gestation period,[76] Jupiter had continued moving in its orbit around the sun and appeared in close conjunction with Venus[75] in June of 2 BC.[77] In Hebrew Jupiter is called "Sedeq", meaning "righteousness", a term also used for the Messiah, and suggested that because the planet Venus represents love and fertility, so Chester had suggested astrologers would have viewed the close conjunction of Jupiter and Venus as indicating a coming new king of Israel, and Herod would have taken them seriously.[70] Astronomer Dave Reneke independently found the June 2 BC planetary conjunction, and noted it would have appeared as a "bright beacon of light".[78] According to Chester, the disks of Jupiter and Venus would have appeared to touch[68] and there has not been as close a Venus-Jupiter conjunction since then.[70]

Jupiter next continued to move and then stopped in its apparent retrograde motion on December 25 of 2 BC over the town of Bethlehem.[75] Since planets in their orbits have a "stationary point",[68][70] a planet moves eastward through the stars but, "As it approaches the opposite point in the sky from the sun, it appears to slow, come to a full stop, and move backward (westward) through the sky for some weeks. Again it slows, stops, and resumes its eastward course," said Chester.[68] The date of December 25 that Jupiter appeared to stop while in retrograde took place in the season of Hanukkah,[68] and is the date later chosen to celebrate Christmas.[75][79]

Heliacal rising

The Magi told Herod that they saw the star "in the East,"[80] or according to some translations, "at its rising",[81] which may imply the routine appearance of a constellation, or an asterism. One theory interprets the phrase in Matthew 2:2, "in the east," as an astrological term concerning a "heliacal rising." This translation was proposed by Edersheim[82] and Heinrich Voigt, among others.[83] The view was rejected by the philologist Franz Boll (1867–1924). Two modern translators of ancient astrological texts insist that the text does not use the technical terms for either a heliacal or an acronycal rising of a star. However, one concedes that Matthew may have used layman's terms for a rising.[84]

Comet

Other writers highly suggest that the star was a comet.[45] Halley's Comet was visible in 12 BC and another object, possibly a comet or nova, was seen by Chinese and Korean stargazers in about 5 BC.[45][85] This object was observed for over seventy days, possibly with no movement recorded.[45] Ancient writers described comets as "hanging over" specific cities, just as the Star of Bethlehem was said to have "stood over" the "place" where Jesus was (the town of Bethlehem).[31] However, this is generally thought unlikely as in ancient times comets were generally seen as bad omens.[86] The comet explanation has been recently promoted by Colin Nicholl. His theory involves a hypothetical comet which could have appeared in 6 BC.[87][88][89]

Supernova

A recent (2005) hypothesis advanced by Frank Tipler is that the star of Bethlehem was a supernova or hypernova occurring in the nearby Andromeda Galaxy.[90] Although it is difficult to detect a supernova remnant in another galaxy, or obtain an accurate date of when it occurred, supernova remnants have been detected in Andromeda.[91]

Another theory is the more likely supernova of February 23 4 BC, which is now known as PSR 1913+16 or the Hulse-Taylor Pulsar. It is said to have appeared in the constellation of Aquila, near the intersection of the winter colure and the equator of date. The nova was "recorded in China, Korea, and Palestine" (probably meaning the Biblical account).[92]

A nova or comet was recorded in China in 4 BC. "In the reign of Ai-ti, in the third year of the Chien-p'ing period. In the third month, day chi-yu, there was a rising po at Hoku" (Han Shu, The History of the Former Han Dynasty). The date is equivalent to April 24, 4 BC. This identifies the date when it was first observed in China. It was also recorded in Korea. "In the fifty-fourth year of Hyokkose Wang, in the spring, second month, day chi-yu, a po-hsing appeared at Hoku" (Samguk Sagi, The Historical Record of the Three Kingdoms). The Korean is particularly corrupt because Ho (1962) points out that " the chi-yu day did not fall in the second month that year but on the first month" (February 23) and on the third month (April 24). The original must have read "day chi-yu, first month" (February 23) or "day chi-yu, third month" (April 24). The latter would coincide with the date in the Chinese records although professor Ho suggests the date was "probably February 23, 4 BC."....[93]

Relating the star historically to Jesus' birth

If the story of the Star of Bethlehem described an actual event, it might identify the year Jesus was born. The Gospel of Matthew describes the birth of Jesus as taking place when Herod was king.[94] According to Josephus, Herod died after a lunar eclipse[95] and before a Passover Feast.[96][97] The eclipse is usually identified as the eclipse of March 13, 4 BC. Other scholars suggested dates in 5 BC, because it allows seven months for the events Josephus documented between the lunar eclipse and the Passover rather than the 29 days allowed by lunar eclipse in 4 BC.[98][99] Others suggest it was an eclipse in 1 BC.[100][101][102] The narrative implies that Jesus was born sometime between the first appearance of the star and the appearance of the Magi at Herod's court. That the king is said to have ordered the execution of boys two years of age and younger implies that the Star of Bethlehem appeared within the preceding two years. Some scholars date the birth of Jesus as 6–4 BC,[103] while others suggest Jesus' birth was in 3–2 BC.[100][101]

The Gospel of Luke says the census from Caesar Augustus took place when Quirinius was governor of Syria.[104] Tipler suggests this took place in AD 6, nine years after the death of Herod, and that the family of Jesus left Bethlehem shortly after the birth.[90] Some scholars explain the apparent disparity as an error on the part of the author of the Gospel of Luke,[105][106] concluding that he was more concerned with creating a symbolic narrative than a historical account,[107] and was either unaware of, or indifferent to, the chronological difficulty.[108]

However, there is some debate among Bible translators about the correct reading of Luke 2:2 ("Αὕτη ἀπογραφὴ πρώτη ἐγένετο ἡγεμονεύοντος τῆς Συρίας Κυρηνίου").[109] Instead of translating the registration as taking place "when" Quirinius was governor of Syria, some versions translate it as "before"[110][111] or use "before" as an alternative,[112][113][114] which Harold Hoehner, F.F. Bruce, Ben Witherington and others have suggested may be the correct translation.[115] While not in agreement, Emil Schürer also acknowledged that such a translation can be justified grammatically.[116] According to Josephus, the tax census conducted by the Roman senator Quirinius particularly irritated the Jews, and was one of the causes of the Zealot movement of armed resistance to Rome.[117] From this perspective, Luke may have been trying to differentiate the census at the time of Jesus’ birth from the tax census mentioned in Acts 5:37[118] that took place under Quirinius at a later time.[119] One ancient writer identified the census at Jesus’ birth, not with taxes, but with a universal pledge of allegiance to the emperor.[120]

Jack Finegan noted some early writers' reckoning of the regnal years of Augustus are the equivalent to 3/2 BC, or 2 BC or later for the birth of Jesus, including Irenaeus (3/2 BC), Clement of Alexandria (3/2 BC), Tertullian (3/2 BC), Julius Africanus (3/2 BC), Hippolytus of Rome (3/2 BC), Hippolytus of Thebes (3/2 BC), Origen (3/2 BC), Eusebius of Caesarea (3/2 BC), Epiphanius of Salamis (3/2 BC), Cassiodorus Senator (3 BC), Paulus Orosius (2 BC), Dionysus Exiguus (1 BC), and Chronographer of the Year 354 (AD 1).[121] Finegan places the death of Herod in 1 BC, and says if Jesus was born two years or less before Herod the Great died, the birth of Jesus would have been in 3 or 2 BC.[122] Finegan also notes the Alogi reckoned Christ's birth with the equivalent of 4 BC or AD 9.[123]

Religious interpretations

Eastern Orthodoxy

In the Orthodox Church, the Star of Bethlehem is interpreted as a miraculous event of symbolic and pedagogical significance, regardless of whether it coincides with a natural phenomenon; a sign sent by God to lead the Magi to the Christ Child. This is illustrated in the Troparion of the Nativity:

Your birth, O Christ our God,

dawned the light of knowledge upon the earth.

For by Your birth those who adored stars

were taught by a star

to worship You, the Sun of Justice,

and to know You, Orient from on High.

O Lord, glory to You.[124]

In Orthodox Christian iconography, the Star of Bethlehem is often depicted not as golden, but as a dark aureola, a semicircle at the top of the icon, indicating the Uncreated Light of Divine grace, with a ray pointing to "the place where the young child lay" (Matt 2:9). Sometimes the faint image of an angel is drawn inside the aureola.

Simon the Athonite founded the monastery of Simonopetra on Mount Athos after seeing a star he identified with the Star of Bethlehem.[125]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

LDS members believe that the Star of Bethlehem was an actual astronomical event visible the world over.[126] In the 1830 Book of Mormon, which they believe contains writings of ancient prophets, Samuel the Lamanite prophesies that a new star will appear as a sign that Jesus has been born, and Nephi later writes about the fulfillment of this prophecy.[127]

Jehovah's Witnesses

Members of Jehovah's Witnesses believe that the "star" was a vision or sign created by Satan, rather than a sign from God. This is because it led the pagan astrologers first to Jerusalem where King Herod consequently found out about the birth of the "king of the Jews", with the result that he attempted to have Jesus killed.[128]

Seventh-day Adventist

In her 1898 book, The Desire of Ages, Ellen White states "That star was a distant company of shining angels, but of this the wise men were ignorant."[129]

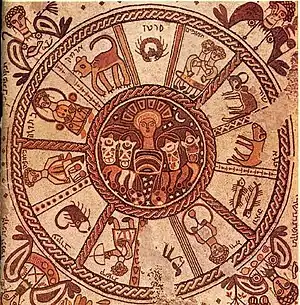

Depiction in art

Paintings and other pictures of the Adoration of the Magi may include a depiction of the star in some form. In the fresco by Giotto di Bondone, it is depicted as a comet. In the tapestry of the subject designed by Edward Burne-Jones (and in the related watercolour), the star is held by an angel.

The colourful star lantern known as a paról is a cherished and ubiquitous symbol of Christmas for Filipinos, its design and light recalling the star. In its basic form, the paról has five points and two "tails" that evoke rays of light pointing the way to the Christ Child, and candles inside the lanterns have been superseded by electric illumination.

In the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, a silver star with 14 undulating rays marks the location traditionally claimed to be that of Jesus' birth.

In quilting, a common eight-pointed star design is known as the Star of Bethlehem.

See also

- Caesar's Comet[130]

- Star of David – The Jewish symbol of King David, which the Star of Bethlehem is often associated with having been a miraculous appearance of.

Notes

- Matthew 2:5–6. Matthew's version is a conflation of Micah 5:2 and 2 Samuel 5:2.

- Matthew 2:16 This is presented as a fulfillment of a prophecy and echoes the killing of firstborn by pharaoh in Exodus 11:1–12:36.

- Judges 13:5–7 is sometimes identified as the source for Matthew 2:23 because Septuagint ναζιραιον (Nazirite) resembles Matthew's Ναζωραῖος (Nazorean). But few scholars accept the view that Jesus was a Nazirite.

- Augustus' mother was said to have become pregnant by the god Apollo and there was a "public portent" indicating that a king of Rome would soon be born. (Suetonius, C. Tranquillus, "The Divine Augustus", The Lives of the Twelve Caesars chapter 94, archived from the original on 2006-09-20).

References

- A Christmas Star for SOHO, NASA, archived from the original on December 24, 2004, retrieved 2008-07-04.

- Matthew 2:1–2

- Matthew 2:11–12

- Freed, Edwin D. (2001), The Stories of Jesus' Birth: A Critical Introduction, Continuum International, p. 93, ISBN 0-567-08046-3

- Telegraph (2008-12-09), "Jesus was born in June", The Daily Telegraph, London, retrieved 2011-12-14.

- "Star of Bethlehem." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005.

- For example, Paul L. Maier, "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem", in Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), 171; Geza Vermes, The Nativity: History and Legend, London: Penguin, 2006, p. 22; E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, 1993, p. 85; Aaron Michael Adair, "Science, Scholarship and Bethlehem's Starry Night", Sky and Telescope, Dec. 2007, pp. 26–29 (reviewing astronomical theories).

- John, Mosley. "Common Errors in 'Star of Bethlehem' Planetarium Shows". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-06-05..

- Andrews, Samuel James (2020). "When did the Magi visit?". Salem Web Network. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Ratti, John, First Sunday after the Epiphany, archived from the original on 2008-06-13, retrieved 2008-06-05.

- Luke chapter 2, verses 17 and 27. Retrieved on December 15, 2019.

- Brown 1988, p. 11.

- Matthew 2:1–11 Revised Standard Version.

- Thomas G. Long, Matthew (Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), p. 18.

- Matthew 2:4.

- Matthew 2:8.

- Matthew 2:12.

- Matthew 2:13–14

- Matthew 2:15 The original is from Hosea 11:1.

- "An Exodus motif prevails in the entire chapter." (Kennedy, Joel (2008), Recapitulation of Israel, Mohr Siebeck, p. 132, ISBN 978-3-16-149825-1, retrieved 2009-07-04).

- Matthew 2:10–21

- Matthew 2:23

- Concordances on the meaning of the word "netzer" on Bible Hub. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- Commentaries for Matthew 2:23 on Bible Hub. Retrieved on December 29, 2005.

- Isaiah chapter 11, verse 1 on Bible Hub with commentaries. Retrieved on December 29, 2015.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1993), The Birth of the Messiah, Anchor Bible Reference Library, p. 188.

- Markus Bockmuehl, This Jesus (Continuum International, 2004), p. 28; Vermes, Géza (2006-11-02), The Nativity: History and Legend, Penguin Books Ltd, p. 22, ISBN 0-14-102446-1; Sanders, Ed Parish (1993), The Historical Figure of Jesus, London: Allen Lane, p. 85, ISBN 0-7139-9059-7; Believable Christianity: A lecture in the annual October series on Radical Christian Faith at Carrs Lane URC Church, Birmingham, October 5, 2006.

- Nikkos Kokkinos, "The Relative Chronology of the Nativity in Tertullian", in Ray Summers, Jerry Vardaman and others, eds., Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), pp. 125–26.

Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar, The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus, HarperSanFrancisco, 1999, ISBN 0-06-062979-7. pp. 499, 521, 533.

Paul L. Maier, "Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem", in Chronos, Kairos, Christos II, Mercer University Press (1998), 171.

For Micah's prophecy, see Micah 5:2. - Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus: apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium, Oxford University Press 1999, p. 38.

- Nolland, p. 110.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, II vi 28. - Jenkins, R.M. (June 2004). "The Star of Bethlehem and the Comet of AD 66" (PDF). Journal of the British Astronomy Association (114). pp. 336–43. Retrieved 2016-12-23.

- Matthew 2:12

- Vermes, Geza (December 2006), "The First Christmas", History Today, 56 (12), pp. 23–29, archived from the original on 2007-12-14, retrieved 2009-07-04.

- Numbers 24:17

- Josephus, Flavius, The Wars of the Jews, retrieved 2008-06-07 Translated by: William Whiston.

Lendering, Jona, Messianic claimants, retrieved 2008-06-05. - Adamantius, Origen. "Contra Celsum". Retrieved 2008-06-05., Book I, Chapter LIX.

- Adamantius, Origen. "Contra Celsum".. Book I, Chapter LX.

- France, R.T., The Gospel according to Matthew: an introduction and commentary, p. 84. See Isaiah 60:1–7 and Psalms 72:10.

- Isaiah 60:6

- Isaiah 60:6 (Septuagint).

- Matthew 2:11

- Schaff, Philip (1886), St. Chrysostom: Homilies on the Gospel of Saint Matthew, New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., p. 36, archived from the original on 2009-02-07, retrieved 2009-07-04.

- Raymond Edward Brown, An Adult Christ at Christmas: Essays on the Three Biblical Christmas Stories, Liturgical Press (1988), p. 11.

- S. J. Tester, A History of Western Astrology, (Boydell & Brewer, 1987), pp. 111–12.

- Mark, Kidger. "Chinese and Babylonian Observations". Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- Minnesota Astronomy Review Volume 18 – Fall 2003/2004 "The Star of Bethlehem by Karlis Kaufmanis" (PDF).

- Audio Version of Star of Bethlehem by Karlis Kaufmanis "The Star of Bethlehem by Karlis Kaufmanis".

- Simo Parpola, "The Magi and the Star," Bible Review, December 2001, pp. 16–23, 52, 54.

- Molnar, Michael. "Revealing the Star of Bethlehem". Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Sinnott, Roger, "Thoughts on the Star of Bethlehem", Sky and Telescope, December 1968, pp. 384–86.

- Greg Garrison (7 March 2019). "Is this what the Star of Bethlehem looked like? Venus, Jupiter put on a show". Alabama Media Group. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Kidger, Mark (2005), Astronomical Enigmas: Life on Mars, the Star of Bethlehem, and Other Milky Way Mysteries, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 63, ISBN 0-8018-8026-2

- Weintraub, David A., "Amazingly, astronomy can explain the biblical Star of Bethlehem", Washington Post, December 26, 2014

- Molnar, Michael R. (1999), The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi, Rutgers University Press, pp. 86, 89, 106–07, ISBN 0-8135-2701-5, archived from the original on 1999-10-12, retrieved 2009-07-04.

- For a similar interpretation, see Minnesota Astronomy Review Volume 18 – Fall 2003/2004 "The Star of Bethlehem by Karlis Kaufmanis" (PDF).

- Stenger, Richard (December 27, 2001), "Was Christmas star a double eclipse of Jupiter?", CNN, retrieved 2009-07-04.

- Govier, Gordon. "O Subtle Star of Bethlehem", Christianity Today, Vol. 58, No. 10, p. 19, December 22, 2014

- Kidger, Mark (December 5, 2001), "The Star of Bethlehem", Cambridge Conference Correspondence, retrieved 2007-07-04.

- Matthew chapter 2 on Bible Gateway, Amplified Version with footnotes. Retrieved on December 22, 2015.

- Lawton, Kim. "Christmas star debate gets its due on Epiphany". USA Today. January 5, 2008. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Herzog, Travis. "Did the Star of Bethlehem exist?" abc13 Eyewitness News. December 20, 2007. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Matthew chapter 2, verse 2. Bible Hub with commentaries. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Matthew chapter 2, verse 3. Bible Hub with commentaries. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Matthew chapter 2 verse 7. Bible Hub with commentaries. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Matthew chapter 2, verses 2–10. Bible Hub with whole chapter and commentaries. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Gospel of Matthew chapter 2 verse 9. Bible Hub with commentaries. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Ireland, Michael. "Evidence emerges for Star of Bethlehem’s reality". Assist News Service. Christian Headlines. October 18, 2007. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Chester, Craig. "The Star of Bethlehem". Imprimis. December 1993, 22(12). Originally presented at Hillsdale College during fall 1992. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Vaughn, Cliff. "The Star of Bethlehem". Ethics Daily. November 26, 2009. Retrieved on January 2, 2016.

- Scripps Howard News Service. "Astronomer Analyzes The Star Of Bethlehem". The Chicago Tribune. December 24, 1993. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Martin, Ernest. 1991 The Star that Astonished the World. ASK Publications. Can be read for free online, for personal study only. Other uses prohibited. Retrieved on February 12, 2016. ISBN 9780945657880

- Lawton, Kim. "Star of Bethlehem". Interview with Rick Larson. PBS, Religion & Ethics Newsweekly. December 21, 2007. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- Rao, Joe. "Was the Star of Bethlehem a star, comet … or miracle?" NBC News. Updated December 12, 2011. Includes a brief interactive at the bottom, “What’s the story behind the Star?” showing retrograde motion and the 3–2 BC planetary conjunctions. Retrieved on January 2, 2016.

- Larson, Frederick. "A coronation" Description of Jupiter as king planet. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- Foust, Michael. Baptist Press. December 14, 2007. Retrieved on December 19, 2015.

- The Free Dictionary by Farlex; Medical Dictionary. Retrieved on February 12, 2016.

- Larson, Frederick. "Westward leading" Description of when Jupiter and Venus aligned. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- Telegraph. "'Jesus was born in June", astronomers claim". The Telegraph. December 9, 2008. Retrieved on December 22, 2015.

- "History of Christmas". History. Retrieved on December 22, 2015.

- Matthew 2:2

- Matthew 2:2. New Revised Standard Version.

- Edersheim, Alfred. The Life and times of Jesus the Messiah. Peabody, (MA: Hendrickson, 1993), several references, chapter 8.

- Adair, Aaron (2013), The Star of Bethlehem: A Skeptical View (Kindle Edition – location 1304), Onus Books, ISBN 978-0956694867

- Roberts, Courtney (2007), The Star of the Magi, Career Press, pp. 120–21, ISBN 978-1564149626

- Colin Humphreys, 'The Star of Bethlehem', in Science and Christian Belief 5 (1995), 83–101.

- Mark Kidger, Astronomical Enigmas: Life on Mars, the Star of Bethlehem, and Other Milky Way Mysteries, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), page 61.

- Colin R. Nicholl. 2015. The Great Christ Comet: Revealing the True Star of Bethlehem. Crossway.

- Interview Greg Cootsona. "What Kind of Astronomical Marvel was the Star of ... - Christianity Today". ChristianityToday.com.

- Guillermo Gonzalez. "The Great Christ Comet: Revealing the True Star of Bethlehem". TGC – The Gospel Coalition.

- Frank J. Tipler (2005). "The Star of Bethlehem: A Type Ia/Ic Supernova in the Andromeda Galaxy?" (PDF). The Observatory. 125: 168–74. Bibcode:2005Obs...125..168T.

- Eugene A. Magnier; Francis A. Primini; Saskia Prins; Jan van Paradijs; Walter H. G. Lewin (1997). "ROSAT HRI Observations of M31 Supernova Remnants" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 490 (2): 649–52. Bibcode:1997ApJ...490..649M. doi:10.1086/304917.

- Morehouse, A. J. (1978). "The Christmas Star as a Supernova in Aquila". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 72: 65. Bibcode:1978JRASC..72...65M.

- McIvor, Robert S. (2005). "The Star on Roman Coins". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 99 (3): 87. Bibcode:2005JRASC..99...87M.

- Matthew 2:1

Luke 2:2 - Josephus, Antiquities XVII:7:4.

- Josephus, Flavius. ~AD 93. Antiquities of the Jews. Book 17, chapter 9, paragraph 3 (17.9.3) Bible Study Tools website. First sentence of paragraph 3 reads: "Now, upon the approach of that feast ..." Retrieved on March 16, 2016.

- Josephus, Flavius. ~93 AD. The War of the Jews. Book 2, chapter 1, paragraph 3 (2.1.3) Bible Study Tools website. About one-third through paragraph three it reads: "And indeed, at the feast ...". Retrieved on March 16, 2016.

- Timothy David Barnes, "The Date of Herod’s Death," Journal of Theological Studies ns 19 (1968), 204–19.

P. M. Bernegger, "Affirmation of Herod’s Death in 4 B.C.," Journal of Theological Studies ns 34 (1983), 526–31. - Finegan, Jack. Handbook of Biblical Chronology: Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998. p. 300. ISBN 1565631439

- Andrew Steinmann, From Abraham to Paul: A Biblical Chronology. (St. Louis, MO: Concordia Pub. House, 2011), Print. pp. 219–56.

- W.E. Filmer, "The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great". The Journal of Theological Studies, 1966. 17(2): pp. 283–98.

- Finegan, Jack. Handbook of Biblical Chronology: Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998, 2015. pp. 238–79.

- Jesus Christ. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010.

- Luke 2:2 Luke chapter 2 verse in parallel translations on Bible Hub. Retrieved on March 3, 2016.

- Ralph Martin Novak, Christianity and the Roman Empire: background texts (Continuum International, 2001), p. 293.

- Raymond E. Brown, Christ in the Gospels of the Liturgical Year, (Liturgical Press, 2008), p. 114. See, for example, James Douglas Grant Dunn, Jesus Remembered, (Eerdmans, 2003) p. 344. Similarly, Erich S. Gruen, 'The expansion of the empire under Augustus', in The Cambridge ancient history Volume 10, p. 157, Geza Vermes, The Nativity, Penguin 2006, p. 96, W. D. Davies and E. P. Sanders, 'Jesus from the Jewish point of view', in The Cambridge History of Judaism ed William Horbury, vol 3: the Early Roman Period, 1984, Anthony Harvey, A Companion to the New Testament (Cambridge University Press 2004), p. 221, Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. Doubleday, 1991, v. 1, p. 213, Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke. London: G. Chapman, 1977, p. 554, A. N. Sherwin-White, pp. 166–67, Millar, Fergus (1990). "Reflections on the trials of Jesus". A Tribute to Geza Vermes: Essays on Jewish and Christian Literature and History (JSOT Suppl. 100) [eds. P.R. Davies and R.T. White]. Sheffield: JSOT Press. pp. 355–81. repr. in Millar, Fergus (2006). "The Greek World, the Jews, and the East". Rome, the Greek World and the East. University of North Carolina Press. 3: 139–63.

- Marcus J. Borg, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time: The Historical Jesus and the Heart of Contemporary Faith, (HarperCollins, 1993), p. 24.

- Elias Joseph Bickerman, Studies in Jewish and Christian History, p. 104.

- Luke 2:2 commentaries on Bible Hub. Retrieved on March 3, 2016.

- Wright, N. T. 2011. The Kingdom New Testament: A Contemporary Translation. Luke 2:2. New York, HarperOne. ISBN 978-0062064912

- Luke 2:2 in the Orthodox Jewish Bible (OJB) on BibleGateway. Retrieved on March 3, 2016.

- Luke 2:2 in the New International Version NIV) Bible on BibleGateway. Retrieved on March 3, 2016.

- Luke 2:2 in the English Standard Version (ESV) Bible on BibleGateway. Retrieved on March 3, 2016.

- Luke 2:2 in Holman Christian Standard Bible (HSCB) on BibleGateway. Retrieved on March 3, 2016.

- Brindle, Wayne. "The Census And Quirinius: Luke 2:2." JETS 27/1 (March 1984) 43–52. Other scholars cited in Brindle's article include A. Higgins, N. Turner, P. Barnett, I. H. Marshall and C. Evan.

- Emil Schürer, Géza Vermès, and Fergus Millar, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.–A.D. 135), (Edinburgh: Clark, 1973 and 1987), 421.

- Josephus, Flavius. ~93 AD. Antiquities of the Jews. Book 18, chapter 1, paragraph 1 (hereafter noted as 18.1.1) Entire book free to read online. Bible Study Tools website. Scroll down from 18.1.1 to find Jewish revolt also mentioned in 18.1.6. Retrieved on March 3, 2016.

- Acts of the Apostles, chapter 5, verse 2 with commentaries. Bible Hub. Retrieved on March 16, 2016.

- Vincent, Marvin R. Vincent's Word Studies. Luke chapter 2, verse 2. Bible Hub. Retrieved on March 16, 2016.

- Paulus Orosius, Historiae Adversus Paganos, VI.22.7 and VII.2.16.

- Finegan, Jack. Handbook of Biblical Chronology: Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998. pp. 279–92.

- Finegan, Jack. Handbook of Biblical Chronology: Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998. p. 301.

- Finegan, Jack. Handbook of Biblical Chronology: Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998. pp. 289–90.

- "Hymns of the Feast". Feast of the Nativity of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. 2009.

- Venerable Simon the Myrrh-gusher of Mt Athos at oca.org, accessed 31 October 2017.

- Smith, Paul Thomas (December 1997), "Birth of the Messiah", Ensign

- Helaman 14:5; 3 Nephi 1:21

- Jesus – The Way, the Truth, the Life, ch. 7: Astrologers Visit Jesus

- The Desire of Ages, p. 60.

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 2.93-94.

Bibliography

- Brown, Raymond E. (1973). The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0809117680.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1999). The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300140088.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1988). An Adult Christ at Christmas: Essays on the Three Biblical Christmas Stories. Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8028-3931-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Star of Bethlehem. |

- Case, Shirley Jackson (2006). Jesus: A New Biography, Gorgias Press LLC: New Ed. ISBN 1-59333-475-3.

- Coates, Richard (2008) 'A linguist's angle on the Star of Bethlehem', Astronomy and Geophysics, 49, pp. 27–49

- Consolmagno S.J., Guy (2010) Looking for a star or Coming to Adore?

- Gill, Victoria: Star of Bethlehem: the astronomical explanations and Reading the Stars by Helen Jacobus with link to, Jacobus, Helen, Ancient astrology: how sages read the heavens/ Did the heavens predict a king?, BBC

- Jenkins, R.M., "The Star of Bethlehem and the Comet of 66AD", Journal of the British Astronomy Association, June 2004, 114, pp. 336–43. This article argues that the Star of Bethlehem is a historical fiction influenced by the appearance of Halley's Comet in AD 66.

- Larson, Frederick A. What Was the Star?

- Nicholl, Colin R., The Great Christ Comet: Revealing the True Star of Bethlehem. Crossway, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4335-4213-8

- Star of Bethlehem Bibliography. Provides an extensive bibliography with Web links to online sources.

Life of Jesus: The Nativity | ||

Infant Jesus at the Temple |

Events |

Adoration of the Wise Men |

.jpg.webp)