Growth of the Old Swiss Confederacy

The Old Swiss Confederacy began as a late medieval alliance between the communities of the valleys in the Central Alps, at the time part of the Holy Roman Empire, to facilitate the management of common interests such as free trade and to ensure the peace along the important trade routes through the mountains. The Hohenstaufen emperors had granted these valleys reichsfrei status in the early 13th century. As reichsfrei regions, the cantons (or regions) of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden were under the direct authority of the emperor without any intermediate liege lords and thus were largely autonomous.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Switzerland |

|

| Early history |

| Old Swiss Confederacy |

|

| Transitional period |

|

| Modern history |

|

| Timeline |

| Topical |

|

|

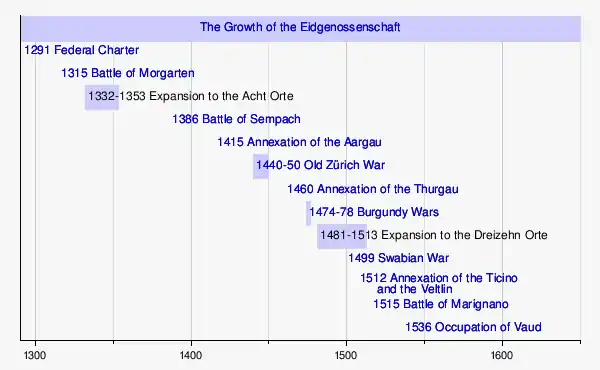

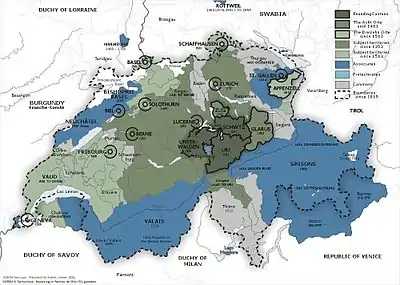

With the rise of the Habsburg dynasty, the kings and dukes of Habsburg sought to extend their influence over this region and to bring it under their rule; as a consequence, a conflict ensued between the Habsburgs and these mountain communities who tried to defend their privileged status as reichsfrei regions. The three founding cantons of the Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, as the confederacy was called, were joined in the early 14th century by the city states of Lucerne, Zürich, and Bern, and they managed to defeat Habsburg armies on several occasions. They also profited from the fact that the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, for most of the 14th century, came from the House of Luxembourg and regarded them as potential useful allies against the rival Habsburgs.

By 1460, the confederates controlled most of the territory south and west of the Rhine to the Alps and the Jura mountains. At the end of the 15th century, two wars resulted in an expansion to thirteen cantons (Dreizehn Orte): in the Burgundian Wars of the 1470s, the confederates asserted their hegemony on the western border, and their victory in the Swabian War in 1499 against the forces of the Habsburg emperor Maximilian I ensured a de facto independence from the empire. During their involvement in the Italian Wars, the Swiss brought the Ticino under their control.

Two similar federations sprung up in neighboring areas in the Alps in the 14th century: in the Grisons, the federation of the Three Leagues (Drei Bünde) was founded, and in the Valais, the Seven Tenths (Sieben Zenden) were formed as a result of the conflicts with the Dukes of Savoy. Neither federation was part of the medieval Eidgenossenschaft but both maintained very close connections with it.

Territorial development

Under the Hohenstaufen dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire, the three regions of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden (the Waldstätten or "forest communities") had gained the Reichsfreiheit, the first two because the emperors wanted to place the strategically important pass of the St. Gotthard under their direct control, the latter because most of its territory belonged to reichsfrei monasteries. The cities of Bern and Zürich had also become reichsfrei when the dynasty of their patrons, the Zähringer, had died out.

When Rudolph I of Habsburg was elected "King of the Germans" in 1273, he also became the direct liege lord of these reichsfrei regions. He instituted a strict rule and raised the taxes to finance wars and further territorial acquisitions. When he died in 1291, his son Albert I got involved in a power struggle with Adolf of Nassau for the German throne, and the Habsburg rule over the alpine territories weakened temporarily. Anti-Habsburg insurgences sprung up in Swabia and Austria, but were quashed quickly by Albert in 1292. Zürich had participated in this uprising. Albert besieged the city, which had to accept him as its patron.

This time of turmoil prompted the Waldstätten to cooperate more closely, trying to preserve or regain their Reichsfreiheit. The first alliance started in 1291 when Rudolph bought all the rights over the town of Lucerne and the abbey estates in Unterwalden from Murbach Abbey in Alsace. The Waldstätten saw their trade route over Lake Lucerne cut off and feared losing their independence. When Rudolph died on July 15, 1291 the Communities prepared to defend themselves. On August 1, 1291 an Everlasting League was made between the Forest Communities for mutual defense against a common enemy.[1] Uri and Schwyz got their status reconfirmed by Adolf of Nassau in 1297,[2] but to no avail, for Albert finally won the power struggle and became emperor in 1298 after Adolf was killed in the Battle of Göllheim.

Nucleus

The Federal Charter of 1291 is one of the oldest surviving written document of an alliance between Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden, the founding cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. It is possible that it was written a few decades later than the given date of 1291, which would put it in the same date range as the pact of Brunnen of 1315. The traditional date given for the foundation of the Swiss Confederacy in Swiss historiography of the 16th century (Aegidius Tschudi and others) is 1307.

1291 marks the death of king Rudolf I, and 1307 falls into the reign of king Albert I, both members of the House of Habsburg ruling in a time of political instability, when the Holy Roman Empire had been without emperor for several decades. The politically weak kings of this period had to make frequent concessions to their subjects and vassals in order to remain in power. The founding cantons received confirmations of the Freibriefe establishing their reichsfrei status. Even Unterwalden was finally properly granted this status by Albert's successor Henry VII in 1309. This did not prevent the dukes of Habsburg, who originally had had their homelands in the Aargau, from trying to reassert their sovereignty over the territories south of the Rhine.

In the struggle for the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in 1314 between duke Frederick I of Austria and the Bavarian king Louis IV, the Waldstätten sided with Louis for fear of the Habsburgs trying to annex their counties again, like Rudolph I had done. When a long-simmering conflict between Schwyz and the abbey of Einsiedeln escalated once more, the Habsburgs responded by sending a strong army of knights against these peasants to subdue their insurrection, but the Austrian army of Frederick's brother Leopold I was utterly defeated in the Battle of Morgarten in 1315. The three cantons renewed their alliance in the pact of Brunnen,[3] and Louis IV reconfirmed their Reichsfreiheit.[4]

The Swiss chronicles of the Burgundy Wars period (1470s) refer to a rebellion against the local bailiffs, with a coordinated destruction of their forts or castles, known as the Burgenbruch ("slighting") in Swiss historiography. The earliest reference for this is the White Book of Sarnen (1470), which records that

- wa böse Türnli waren, die brachen sy vnd viengen ze Uere am ersten an die hüser brechen

- "wherever there were hostile forts (towers), they broke (slighted) them and first began in Uri to break these buildings"[5]

The text names Zwing Uri at Amsteg as the first castle slighted, followed by castle Schwandau in Schwyz, Rötzberg in Stans, and finally the castle at Sarnen, the storming of which is told in a graphic manner.[6]

The Burgenbruch was long seen as historical, substantiated by the numerous ruined castles in Central Switzerland, but archaeological excavations have shown that these castles were abandoned gradually, not during a sudden uprising, during the period of roughly 1200 to 1350. By the 1970s, the "demythologization" of the foundational period of the Confederacy was at its peak, and the default view was to regard the reports of the late-15th-century chronists as essentially legendary. Since the late 1970s, systematic surveys of medieval castles in Central Switzerland have shown that a number of castles were indeed destroyed during the early 14th century, so that a possible historical nucleus of the Burgenbruch accounts may be granted, even though the destruction of these forts in itself was of limited military import and could not have resulted in a lasting political change.[7]

Expansion to the Acht Orte

Subsequently, the three communities (their territories did not yet correspond to the areas of the modern-day cantons) followed a slow policy of expansion. Uri entered a pact with the previously Habsburg valley of Urseren in 1317. In 1332,[3] the city of Lucerne, trying to achieve Reichsfreiheit from the Habsburgs, joined the alliance. In 1351, these four communities were joined by the city of Zürich, where a strong citizenship had gained power following the installation of the Zunftordnung (guild regulations) and the banning of the noble authorities in 1336.[2] The city also sought support against the Habsburg city of Rapperswil, which had tried to overthrow mayor Rudolf Brun in Zürich in 1350. With the help of its new allies, Zürich was able to withstand the siege of duke Albert II of Austria, and the confederates even conquered the city of Zug[2] and the valley of Glarus in 1352.[3] They had to return both Glarus and Zug to the Habsburgs in the peace treaty of Regensburg in 1356; emperor Charles IV in return recognized the Zunftordnung of Zürich and confirmed its reichsfrei status in spite of his having forbidden any confederations within the empire in his Golden Bull issued in January of that same year.

The Eidgenossenschaft had signed "perpetual" pacts with both Glarus and Zug in 1352,[3] and thus, even if these pacts apparently were disregarded only a few years later, this date is often considered the entry of these two cantons into the confederation despite their remaining under Habsburg rule for a few more years.[8]

In the west, the Vier Waldstätten had already formed an alliance with the city of Bern in 1323, and even sent a detachment to help the Bernese forces in their territorial expansion against the dukes of Savoy and the Habsburgs in the Battle of Laupen in 1339.[2] In 1353,[3] Bern entered an "eternal" alliance with the confederation, completing the "Confederacy of the Eight Cantons" (German: Bund der Acht Orte).

This alliance of the Acht Orte was not a homogeneous state but rather a conglomerate of eight independent cities and lands, held together not by one single pact but by a net of six different "eternal" pacts, none of which included all eight parties as signatories. Only the three Waldstätten Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden were part of all these treaties. All eight parties would still pursue their own particular interests, most notably in the cases of the strong cities of Zürich and Bern. Zürich was also part of an alliance of cities around Lake Constance which also included Konstanz, Lindau and Schaffhausen and for some time included cities as far away as Rottweil or Ulm, and Bern followed its own hegemonial politics, participating successively in various alliances with other cities including Fribourg, Murten, Biel or Solothurn. This Bernese "Burgundian Confederation" was a more volatile construct of varying alliances, and in the Battle of Laupen (1339), Fribourg even sided against Bern.[9] Bern's position after that battle was strong enough that such alliances often ended with the other party becoming a Bernese dependency, as it happened with e.g. Burgdorf[10] or Payerne.

An external threat during this time arose in the form of the Guglers, marauding mercenary knights from France who were beaten back under the leadership of Bern in December 1375.[11]

Consolidation

In 1364, Schwyz re-conquered the city and land of Zug and renewed the alliance the following year. In the 1380s, Lucerne expanded its territory aggressively, conquering Wolhusen, claiming sovereignty over the valley of the Entlebuch and the formerly Habsburg city of Sempach. As a consequence, Leopold III of Austria assembled an army and met the Eidgenossen near Sempach in 1386, where his troops were defeated decisively in the Battle of Sempach and he himself was killed.[2] In the wake of these events Glarus declared itself free and constituted its first Landsgemeinde (regional diet) in 1387. In the Battle of Näfels in 1388, an Austrian army of Albert III, the successor of Leopold, was defeated, and in the peace treaty concluded the next year, Glarus maintained its independence from the Habsburgs.[2]

The loose federation of states was reinforced by additional agreements amongst the partners. In the Pfaffenbrief of 1370, the signatory six states (without Bern and Glarus) for the first time expressed themselves as a territorial unity, referring to themselves as unser Eydgnosschaft. They assumed in this document authority over clericals, subjecting them to their worldly legislation. Furthermore, the Pfaffenbrief forbade feuds and the parties pledged to guarantee the peace on the road from Zürich to the St. Gotthard pass. Another important treaty was the Sempacherbrief in 1393. Not only was this the first document signed by all eight of the Acht Orte (plus the associated Solothurn), but it also defined that none of them was to unilaterally start a war without the consent of all the others.

Beginning in 1401, the confederates supported the insurrection of Appenzell against the abbey of St. Gallen and Frederick IV of Austria, duke in Tyrol and Vorderösterreich. Appenzell became a protectorate of the Acht Orte in 1411, who concluded a 50-year peace with Frederick IV in 1412.

Emperor Sigismund banned Frederick IV in 1415, who had sided with Antipope John XXIII at the Council of Constance, and encouraged others to take over the duke's possessions, amongst which was the Aargau. After being granted far-reaching privileges by the emperor (all eight cantons became reichsfrei) and a decree that placed the ban over the peace treaty of 1412, the Eidgenossen conquered the Aargau.[12] A large part became Bernese, while the County of Baden was subsequently administered by the confederation as a common property until 1798. Only the Fricktal remained Habsburgian.

In the Valais, the conflict between the Bishop of Sion and the Duchy of Savoy, which had led to a separation in 1301 (the bishop controlling the upper Valais and the Savoyards the lower part), broke out again. Twice the Savoyards temporarily occupied the whole Valais, but both times they were ultimately defeated. Both peace treaties from 1361 and 1391 restored the status quo of 1301. As a result of these struggles, the villages in the upper Valais organized themselves in the Sieben Zenden ("seven tenths") around 1355, emerging after these wars as largely independent small states, much like the cantons of the Eidgenossenschaft.

In the Grisons, called Churwalchen then, the bishop of Chur and numerous local noble families competed for the control of the region with its many alpine passes. Throughout the 14th century, three leagues of free communities appeared. The Gotteshausbund ("League of the House of God"), covering the area around Chur and the Engadin, was founded when in 1367 the bishop, Jean de Vienne, planned to hand over the administration of his diocese to the Austrian Habsburgs.[13] It bought its freedom by paying the bishop's debt and in the following decades increased its control over the secular administration of the princebishopric, until the bishop's regent was deposed in 1452. In the upper valley of the Rhine, the Grauer Bund ("Gray League") was founded in 1395 under the direction of the abbot of Disentis and including not only the peasant communities but also the local nobles to end the permanent feuds of the latter.[14] By 1424 the Gray League was dominated by the free communities and gave itself a more democratic charter. The third league, Zehngerichtenbund ("League of the Ten Jurisdictions"), wouldn't be formed until later.[15]

Internal crisis

The relationships between the individual cantons of the confederation were not without tensions, though. A first clash between Bern and the Vier Waldstätten over the Raron conflict (Bern supported the barons of Raron, while the forest cantons sided with the Sieben Zenden) in the upper Valais was barely avoided. The local noble barons of Raron established themselves as the leading family in the upper Valais in the late 14th century and competed with the bishop of Sion for the control of the valley. When emperor Sigismund designated them counts in 1413 and ordered the bishop to hand over his territories to the von Raron, a revolt broke out in 1414. The following year, both rulers had lost: the von Raron had not succeeded in ousting the bishop, who in turn had to concede far-reaching rights to the Sieben Zenden in the treaty of Seta in 1415.[16]

The Old Zürich War, which began as a dispute over the succession to the count of Toggenburg, was a more serious test of the unity of the Acht Orte. Zürich did not accept the claims of Schwyz and Glarus, which were supported by the rest of the cantons, and in 1438 declared an embargo. The other members of the confederation expelled Zürich from the confederation in 1440 and declared war. In retaliation Zürich made a pact with the Habsburgs in 1442. The other cantons invaded the canton of Zürich and besieged the city, but were unable to capture it. By 1446, both sides were exhausted, and a preliminary peace was concluded. In 1450, the parties made a definitive peace and Zürich was admitted into the confederation again, but had to dissolve its alliance with the Habsburgs. The confederation had grown into a political alliance so close that it no longer tolerated separatist tendencies of its members.[17]

The end of the dynasty of the counts of Toggenburg in 1436 also had effects on the Grisons. In their former territories in the Prättigau and Davos, the (initially eleven, after a merger only ten) villages founded the Zehngerichtebund ("League of the Ten Jurisdictions").[15] By 1471, the three leagues, together with the city of Chur, had formed a close federation, based on military assistance and free trade pacts between the partners and including a common federal diet: the Drei Bünde ("Three Leagues") was born, even though the alliance would be officially concluded in a written contract only in 1524.[18]

Further expansion

In the second half of the 15th century, the confederation expanded its territory further. In the north, the formerly Habsburg cities of Schaffhausen and Stein am Rhein had become reichsfrei in 1415, with the ban of Frederick IV. The two strategically important cities—they offered the only two fortified bridges over the river Rhine between Constance and Basel—not only struggled with the robber barons from the neighbouring Hegau region but also were under pressure from the Habsburg dukes, who sought to re-integrate the cities into their domain. On June 1, 1454, Schaffhausen became an associate (Zugewandter Ort) of the confederacy by entering an alliance with six of the eight cantons (Uri and Unterwalden did not participate). With the help of the confederates, a Habsburg army of about 2,000 men was warded off east of Thayngen. Stein am Rhein concluded a similar alliance on December 6, 1459.

The city of St. Gallen had also become free in 1415, but was in a conflict with its abbot, who tried to bring it under his influence. But as the Habsburg dukes were unable to support him in any way, he was forced to seek help from the confederates, and the abbey became a protectorate of the confederacy on August 17, 1451.[19] The city was accepted as an associate state on June 13, 1454. Fribourg, another Habsburg city, came under the rule of the Duke of Savoy during the 1440s and had to accept the duke as its lord in 1452. Nevertheless, it also entered an alliance with Bern in 1454, becoming an associate state, too. Two other cities also sought help from the Eidgenossen against the Habsburgs: Rottweil became as associate on June 18, 1463, and Mülhausen on June 17, 1466 through an alliance with Bern (and Solothurn). In Rapperswil, a Habsburg enclave on Lake Zürich within confederate territory, a pro-confederate coup d'état in 1458 led to the city becoming a protectorate of the confederacy in 1464.

Duke Sigismund of Austria got involved in a power struggle with Pope Pius II over the nomination of a bishop in Tyrol in 1460. When the duke was banned by the pope, a situation similar to that of 1415 arose. The confederates took advantage of the problems of the Habsburgs and conquered the Habsburg Thurgau and the region of Sargans in the autumn of 1460, which became both commonly administered property. In a peace treaty from June 1, 1461, the duke had no choice but to accept the new situation.

The Swiss also had an interest in extending their influence south of the Alps to secure the trade route across the St. Gotthard Pass to Milan. Beginning in 1331, they initially exerted their influence through peaceful trade agreements, but in the 15th century, their involvement turned military. 1403 the upper Leventina, as the valley south of the pass is called, became a protectorate of Uri. Throughout the 15th century, a changeful struggle between the Swiss and the Duchy of Milan ensued. In 1439, Uri assumed full control of the upper Leventina; the Duchy of Milan gave up its claims there two years later, and so did the chapter of Milan in 1477. Twice the Swiss conquered roughly the whole territory of the modern canton of Ticino and also the Ossola valley. Twice, the Milanese reconquered all these territories except the Leventina. Both times, the Swiss managed, despite their defeats, to negotiate peace treaties that were actually favorable for them.

Burgundy Wars

The Burgundian Wars were an involvement of confederate forces in the conflict between the Valois Dynasty and the Habsburgs. The aggressive expansionism of the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, brought him in conflict with both the French king Louis XI and emperor Frederick III of the House of Habsburg. His embargo politics against the cities of Basel, Strasbourg and Mulhouse prompted these to turn to Bern for help.

The conflicts culminated in 1474, after duke Sigismund of Austria had concluded a peace agreement with the confederates in Constance (later called the Ewige Richtung). The confederates, united with the Alsatian cities and Sigismund in an "anti-burgundian league", conquered part of the Burgundian Jura (Franche-Comté), and the next year, Bernese forces conquered and ravaged the Vaud, which belonged to the Duchy of Savoy, which in turn was allied with Charles the Bold. The Sieben Zenden, with the help of Bernese and other confederate forces, drove the Savoyards out of the lower Valais after a victory in the Battle on the Planta in November 1475. In 1476, Charles retaliated and marched to Grandson with his army, but suffered three devastating defeats in a row, first in the Battle of Grandson, then in the Battle of Murten, until he was killed in the Battle of Nancy in 1477, where the confederates fought alongside an army of René II, Duke of Lorraine.[20] There is a proverbial saying in Switzerland summarizing these events as "Bi Grandson s'Guet, bi Murte de Muet, bi Nancy s'Bluet" (hät de Karl de Küeni verloore) ("[Charles the Bold lost] his goods at Grandson, his boldness at Murten and his blood at Nancy").

As a result of the Burgundy Wars, the dynasty of the dukes of Burgundy had died out. Bern returned the Vaud to the duchy of Savoy against a ransom of 50,000 guilders already in 1476, and sold its claims on the Franche-Comté to Louis XI for 150,000 guilders in 1479. The confederates only kept small territories east of the Jura mountains, especially Grandson and Murten, as common dependencies of Bern and Fribourg. The whole Valais, however, would henceforth be independent, and Bern would reconquer the Vaud in 1536. While the territorial effects of the Burgundy Wars on the confederation were minor, they marked the beginning of the rise of Swiss mercenaries on the battlefields of Europe.

Swiss mercenaries

In the Burgundy Wars, the Swiss soldiers had gained a reputation of near invincibility, and their mercenary services became increasingly sought after by the great European political powers of the time.

Shortly after the Burgundy Wars, individual cantons concluded mercenary contracts, so-called "capitulations", with many parties, including the Pope — the papal Swiss Guard was founded in 1505 and became operational the next year.[21] More contracts were made with France (a Swiss Guard of mercenaries would be destroyed in the storming of the Tuileries Paris in Paris in 1792[22]), the Duchy of Savoy, Austria, and still others. Swiss mercenaries would play an initially important, but later minor role on European battlefields until well into the 18th century.

Swiss forces soon got involved in the Italian Wars between the Valois and the Habsburgs over the control of northern Italy. When the power of the Duchy of Milan perished in these wars, the Swiss finally managed to bring the whole Ticino under their control. In 1500, they occupied the strategically important fortress of Bellinzona, which the French king Louis XII, who ruled Milan at that time, ceded definitively in 1503. From 1512 on, the confederates fought on the side of Pope Julius II and his Holy League against the French in territories south of the Alps. After initial successes and having conquered large parts of the territory of Milan, they were utterly defeated by a French army in the Battle of Marignano in 1515, which put an end to military territorial interventions of the confederation, mercenary services under the flags of foreign armies excepted. The result of this short intermezzo were the gain of the Ticino as a common administrative region of the confederacy and the occupation of the valley of the Adda river (Veltlin, Bormio, and Chiavenna) by the Drei Bünde, which would remain a dependency of the Grisons until 1797 with a brief interruption during the Thirty Years' War.

Dreizehn Orte

Both Fribourg and Solothurn, which had participated in the Burgundy Wars, now wanted to join the confederation, which would have tipped the balance in favour of the city cantons. The rural cantons were thus strongly opposed. In 1477 they marched upon the cities in protest.

At Stans in 1481 a Tagsatzung was held in order to resolve the issues, but war seemed inevitable. A local hermit, Niklaus von der Flüe, was consulted on the situation. He requested that a message be passed on to the members of the Tagsatzung on his behalf. The details of the message have remained unknown to this day, however it did calm the tempers and led to the drawing up of the Stanser Verkommnis. Fribourg and Solothurn were admitted into the confederation.

After isolated bilateral pacts between the leagues in the Grisons and some cantons of the confederation had already existed since the early 15th century, the federation of the Three Leagues as a whole became an associate state of the confederation, in 1498, by concluding alliance agreements with the seven easternmost cantons.

When the confederates refused to accept the resolutions of the Diet of Worms in 1495, the Swabian War (Schwabenkrieg, also called the Schweizerkrieg in Germany) broke out in 1499, opposing the confederation against the Swabian League and emperor Maximilian I. After some battles around Schaffhausen, in the Austrian Vorarlberg and in the Grisons, where the confederates were victorious more often than not, the Battle of Dornach, where the emperor's commander was killed, put an end to the war. In September 1499, a peace agreement was concluded at Basel that effectively established a de facto independence of the Eidgenossenschaft from the empire, although it continued nominally to be part of the Holy Roman Empire until after the Thirty Years' War and was not included into the system of Imperial Circles in 1500.

As a direct consequence of the Swabian War the previously associated city states of Basel and Schaffhausen joined the confederation in 1501.[3] In 1513, the Appenzell followed suit as the thirteenth member.[3] The cities of St. Gallen, Biel, Mulhouse and Rottweil as well as the Three Leagues in the Grisons were all associates of the confederation (Zugewandte Orte); the Valais would become an associate state in 1529.

Annexation of the Ticino and the Veltlin

The Ticino region consisted of several city-states along the Ticino river. Following the conquest of the region, it was divided into four Ticino Bailiwicks which were under the joint administration of the 13 Cantons after 1512. The four bailiwicks were Valle di Maggia (German: Meynthal or Maiental), Locarno (German: Luggarus), Lugano (German: Lugano) and Mendrisio (German: Mendris). The area also included several other territories that were owned by one or more cantons. These included: the Bailiwick of Bellinzona (German: Bellinzona), Blenio (German: Bollenz) and Riviera (German: Reffier) which were owned by Uri, Schwyz, and Nidwalden as well as the bailiwick Leventina (German: Livinental) (owned by Uri) and even the Val d'Ossola (German: Eschental). There were also three Italian-speaking subjects areas of the Three Leagues (Bormio, Valtellina and Chiavenna) which were not included in the Ticino Bailiwicks.[23]

Between 1403 and 1422 some of these lands were annexed by forces from Uri, but subsequently lost after the Battle of Arbedo in 1422. While the Battle of Arbedo stopped Swiss expansion for a time, the Confederation continued to exercise influence in the area. The Canton of Uri conquered the Leventina Valley in 1440.[24] In a second conquest Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden gained the town of Bellinzona and the Riviera in 1500.[24] The third conquest was fought by troops from the entire Confederation (at that time constituted by 12 cantons). In 1512, Locarno, the Maggia Valley, Lugano and Mendrisio were annexed. Subsequently, the upper valley of the Ticino river, from the St. Gotthard to the town of Biasca (Leventina Valley) was part of the Canton of Uri. The remaining territory (Baliaggi Ultramontani, Ennetbergische Vogteien, the Bailiwicks Beyond the Mountains) was administered by the Twelve Cantons. These districts were governed by bailiffs holding office for two years and purchasing it from the members of the League.[24]

Some of the land and the town of Bellinzona were annexed by Uri in 1419 but lost again in 1422. In 1499 nearly one and a half centuries of Milanese rule in Bellinzona ended with the invasion of Milan by Louis XII of France. He captured the city and fearing an attack by the Swiss, fortified the Castelgrande with 1,000 troops.[25] Throughout the winter of 1499/1500 unrest in Bellinzona grew, until January when an armed revolt of the citizens of Bellinzona drove the French troops from the city. Following the capture and execution of Ludovico Sforza in April 1500 and seeking protection from France, Bellinzona joined the Swiss Confederation on April 14, 1500.[26] Bellinzona would remain under the joint administration of Uri, Schwyz and Nidwalden until the creation of the Helvetic Republic after the Napoleonic invasion of Switzerland in 1798.

Between 1433 and 1438 the Duke of Milan, Aloisio Sanseverino sat as a feudal lord over Lugano. Under the reign of his heirs in the following decades rebellions and riots broke out, which lasted until the French invasion of 1499.[27]

Myths and legends

The events told in the saga of William Tell, which are purported to have occurred around 1307, are not substantiated by historical evidence. This story, like the related story of the Rütlischwur (the oath on the Rütli, a meadow above Lake Lucerne), seems to have its origins in the late 15th century Weisse Buch von Sarnen,[28] a collection of folk tales from 1470, and is generally considered a fictitious glorification of the independence struggles of the Waldstätten.

The legend of Arnold von Winkelried likewise is first recorded in the 16th century;[29] earlier accounts of the Battle of Sempach do not mention him. Winkelried is said to have opened a breach in the lines of the Austrian footsoldiers by throwing himself into their lances, taking them down with his body such that the confederates could attack through the opening.

Social developments

The developments beginning in about the 13th century had profound effects on the society. Gradually the population of serfs changed into one of free peasants and citizens. In the cities—which were small by modern standards; Basel had about 10,000 inhabitants,[30] Zürich, Bern, Lausanne, and Fribourg about 5,000 each—the development was a natural one, for the liege lords very soon gave the cities a certain autonomy, in particular over their internal administration. The number of cities also grew during this period. In 1200 there were about 30 cities. A century later, in 1300, there were over 190 interconnected cities.[31] At the beginning of the 14th century, the artisans in the cities began forming guilds and increasingly took over political control, especially in the cities along the Rhine, e.g. in the Alsace, in Basel, Schaffhausen, Zürich, or Chur. (But not, for instance, in Bern or Lucerne—or, in Germany, Frankfurt—where a stronger aristocracy seems to have inhibited such a development.) The guild cities had a relatively democratic structure, with a city council elected by the citizens.

In the rural areas, people generally had less freedom, but some lords furthered the colonization of remote areas by granting some privileges to the colonists.[31] One well-known colonization movement was that of the Walser from the Valais to the Grisons, colonizing some valleys there in the 14th century. In the mountainous areas, a community management of common fields, alps, and forests (the latter being important as a protection against avalanches) soon developed, and the communes in a valley cooperated closely and began buying out the noble landowners or simply to dispossess them of their lands. Regional diets, the Landsgemeinden, were formed to deal with the administration of the commons; it also served as the high court and to elect representatives, the Landamman.

As free farmers moved into the mountain valleys, construction and maintenance of the mountain pass roads became possible. In the 12th and 13th Centuries, the passes into Graubünden and Valais were expanded and developed, which allowed much of the Walser migration. The Gotthard Pass was first opened around the 12th Century, and by 1236 was dedicated to the Bavarian Saint Gotthard of Hildesheim. As the population in the nearby mountain valleys grew, the pass roads continued to expand. With easier and safer roads, as well as increased infrastructure, international trade grew throughout the mountain valleys and Switzerland.[31]

Although both poor and rich citizens or peasants had the same rights (though not the same status), not all people were equal. Immigrants into a village or city had no political rights and were called the Hintersassen. In rural areas, they had to pay for their use of the common lands. They were granted equal rights only when they acquired citizenship, which not only was a question of wealth (for they had to buy their citizenship), but they also had to have lived there for some time; especially in the rural areas.[32]

The cities followed an expansionist territorial politics to gain control over the surrounding rural areas, on which they were dependent, using military powers or more often more subtle means such as buying out, or accepting as citizens the subjects (and thereby freeing them: "Stadtluft macht frei"—"city air liberates") of a liege lord. It was the cities, now, that instituted reeves to manage the administration, but this only sometimes and slowly led to a restriction of the communal autonomy of the villages. The peasants owned their land, the villages kept administering their commons; and the villagers participated in the jury of the city reeve's court. They had, however, to provide military service for the city, which on the other hand included the right to own and carry weapons.

Basel became the center of higher education and science in the second half of the 15th century. The city had hosted the Council of Basel from 1431 to 1447, and, in 1460, a university was founded, which eventually would attract many notable thinkers, such as Erasmus or Paracelsus.

Economy

The population of the cantons numbered about 600,000 in the 15th century and grew to about 800,000 by the 16th century. The grain production sufficed only in some of the lower regions; most areas were dependent on imports of oats, barley, or wheat. In the Alps, where the yield of grains had always been particularly low due to the climatic conditions, a transition from farming to the production of cheese and butter from cow milk occurred. As the roads got better and safer, a lively trade with the cities developed.

The cities were the marketplaces and important trading centers, being located on the major roads through the Alps. Textile manufacture, where St. Gallen was the leading center, developed. Cheese (esp. Emmentaler and Gruyère) also was a major export item. The exports of the Swiss cities went far, into the Levant or to Poland.

In the late 15th century, the mercenary services became also an important economic factor. The Reisläuferei, as the mercenary service was called, attracted many young adventurous Swiss who saw in it a way to escape the relative poverty of their homes. Not only the mercenaries themselves were paid, but also their home cantons, and the Reisläuferei, while being heavily criticized already at that time as a heavy drain on the human resources of the confederation, became popular in particular among the young peasants from the rural cantons.

Political organization

Initially, the Eidgenossenschaft was not united by one single pact, but rather by a whole set of overlapping pacts and separate bilateral treaties between various members, with only minimum liabilities. The parties generally agreed to preserve the peace in their territories, help each other in military endeavours, and defined some arbitration in case of disputes. The Sempacherbrief from 1393 was the first treaty uniting all eight cantons, and subsequently, a kind of federal diet, the Tagsatzung developed in the 15th century. The second unifying treaty later became the Stanser Verkommnis in 1481.

The Tagsatzung typically met several times a year. Each canton delegated two representatives; typically this also included the associate states. Initially, the canton where the delegates met chaired the gathering, but in the 16th century, Zürich permanently assumed the chair (Vorort), and Baden became the sessional seat.[33]

The Tagsatzung dealt with all inter-cantonal affairs and also served as the final arbitral court to settle disputes between member states, or to decide on sanctions against dissenting members, as happened in the Old Zürich War. It also organized and oversaw the administration of the commons such as the County of Baden and the neighbouring Freiamt, the Thurgau, in the Rhine valley between Lake Constance and Chur, or those in the Ticino. The reeves for these commons were delegated for two years, each time by a different canton.

Despite its informal character (there was no formal legal base describing its competencies), the Tagsatzung was an important instrument of the eight, later thirteen cantons to decide inter-cantonal matters. It also proved instrumental in the development of a sense of unity among these sometimes highly individual cantons. Slowly, they defined themselves as the Eidgenossenschaft and considered themselves less as thirteen separate states with only loose bonds between.

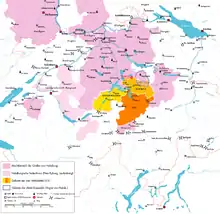

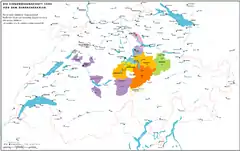

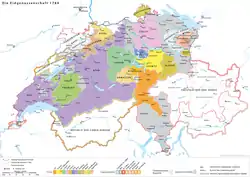

Maps showing the growth of the Old Swiss Confederacy

Territorial development of Old Swiss Confederacy, 1291–1797

Territorial development of Old Swiss Confederacy, 1291–1797 Switzerland in 1315, just before the Battle of Morgarten.

Switzerland in 1315, just before the Battle of Morgarten. Switzerland in 1385, just before the Battle of Sempach.

Switzerland in 1385, just before the Battle of Sempach. Switzerland in 1474, just before the Burgundian Wars.

Switzerland in 1474, just before the Burgundian Wars. Switzerland in 1515, just before the Battle of Marignano.

Switzerland in 1515, just before the Battle of Marignano.

Switzerland in the 18th century.

Switzerland in the 18th century. Another map of Swtizerland in the 18th Century.

Another map of Swtizerland in the 18th Century.

See also

References

Main sources:

- Im Hof, U.: Geschichte der Schweiz, 7th ed., Kohlhammer Verlag, 1974/2001. ISBN 3-17-017051-1.

- Schwabe & Co.: Geschichte der Schweiz und der Schweizer, Schwabe & Co 1986/2004. ISBN 3-7965-2067-7.

Other sources:

- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 247.

- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 248–250.

- History and Creation of the Confederation to 1353 in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Battle of Morgarten and Aftermath in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- cited after Ernst Ludwig Rochholz,, Tell und Gessler in Sage und Geschichte. Nach urkundlichen Quellen (1877), p. 119.

- for an English translation see William Denison McCrackan, The rise of the Swiss republic. A history (1892), p. 107.

- W. Meyer et al., Die bösen Türnli: Archäologische Beiträge zur Burgenforschung in der Urschweiz, Schweizer Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters, vol 11, Schweizerischer Burgenverein, Olten / Freiburg i.Br. 1984, pp. 192–194.

- Glauser, T.: 1352 – Zug wird nicht eidgenössisch Archived 2004-08-27 at the Wayback Machine, State archive of the Canton of Zug; Tugium 18, pp. 103–115; 2002. (PDF file, 359 KB; in German).

- Rickard, J (4 October 2000). "Battle of Laupen, 21 June 1339". Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- Burgdorf War in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland. Following the 1383–84 attack by Burgdorf on Soloturn, the city was defeated and bought by Bern for 37,800 Gulden

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1978). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. Ballantine Books. pp. 278. ISBN 0-345-34957-1.

- Aargau, Aargau becomes part of the Confederation in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- League of God's House in Romansh, German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Grauer Bund in Romansh, German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- League of the Ten Jurisdictions in Romansh, German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Raron Quarrel in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Old Zurich War in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Graubünden in Romansh, German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 4.

- Sieber-Lehmann, C.: The Burgundy Wars in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.; January 18, 2005.

- History of the Pontifical Swiss Guards Official Vatican web page, Roman Curia, Swiss Guards, retrieved February 9, 2009

- Information from the Glacier Garden in Lucerne accessed 9 February 2009

- Italian Bailiwicks in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 933–934.

- Official Site-Bellinzona joins the Confederation Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine accessed July 17, 2008

- Bellinzona-The Middle Ages in .php German, .php French and .php Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Lugano – During the Middle Ages in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Bergier, Jean-François (1990). Wilhelm Tell: Realität und Mythos. München: Paul List Verlag. p. 63. ISBN 3-471-77168-9.

- Swissworld.org Confederate victories undermine the power of the nobility accessed 5 February 2009

- Basel City, Population in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Niklaus Flüeler; Roland Gfeller-Corthésy (1975). Die Schweiz vom Bau der Alpen bis zur Frage nach der Zukunft: ein Nachschlagewerk und Lesebuch, das Auskunft gibt über Geographie, Geschichte, Gegenwart und Zukunft eines Landes (in German). Migros-Genossenschafts-Bund. p. 88. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- Holenstein, A.: Hintersassen in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.; September 5, 2005.

Further reading

- Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in German, French, Italian and Rumanch)

- Luck, James M.: A History of Switzerland / The First 100,000 Years: Before the Beginnings to the Days of the Present, Society for the Promotion of Science & Scholarship, Palo Alto 1986. ISBN 0-930664-06-X.

- Schneider, B. (ed.): Alltag in der Schweiz seit 1300, Chronos 1991; in German. ISBN 3-905278-70-7.

- Stettler, B: Die Eidgenossenschaft im 15. Jahrhundert, Widmer-Dean 2004; in German. ISBN 3-9522927-0-2.

External links

- The Old Swiss Confederation by Markus Jud (in English and German).

- Switzerland in the Middle Ages by "Presence Switzerland", an official body of the Swiss Confederation. (In English, available also in many other languages.)