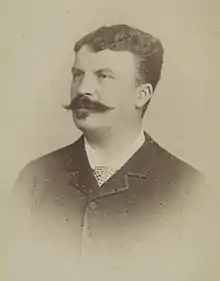

Guy de Maupassant

Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant (UK: /ˈmoʊpæsɒ̃/,[1][2] US: /ˈmoʊpəsɒnt, ˌmoʊpəˈsɒ̃/;[2][3][4][5] French: [ɡi d(ə) mopasɑ̃]; 5 August 1850 – 6 July 1893) was a 19th-century French author, remembered as a master of the short story form, and as a representative of the Naturalist school, who depicted human lives and destinies and social forces in disillusioned and often pessimistic terms.

Guy de Maupassant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant 5 August 1850 Tourville-sur-Arques, French Republic |

| Died | 6 July 1893 (aged 42) Passy, Paris, French Republic |

| Resting place | Montparnasse Cemetery |

| Pen name | Guy de Valmont, Joseph Prunier |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, poet |

| Genre | Naturalism, Realism |

| Signature |  |

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Maupassant was a protégé of Gustave Flaubert and his stories are characterized by economy of style and efficient, seemingly effortless dénouements. Many are set during the Franco-Prussian War of the 1870s, describing the futility of war and the innocent civilians who, caught up in events beyond their control, are permanently changed by their experiences. He wrote 300 short stories, six novels, three travel books, and one volume of verse. His first published story, "Boule de Suif" ("The Dumpling", 1880), is often considered his masterpiece.

Biography

Henri-René-Albert-Guy de Maupassant was born on 5 August 1850 at the late-16th century Château de Miromesnil, near Dieppe in the Seine-Inférieure (now Seine-Maritime) department in France. He was the first son of Laure Le Poittevin and Gustave de Maupassant, both from prosperous bourgeois families. His mother urged his father when they married in 1846 to obtain the right to use the particule or form "de Maupassant" instead of "Maupassant" as his family name, in order to indicate noble birth.[6] Gustave discovered a certain Jean-Baptiste Maupassant, conseiller-secrétaire to the King, who was ennobled in 1752.[6] He then obtained from the Tribunal Civil of Rouen by decree dated 9 July 1846 the right to style himself "de Maupassant" instead of "Maupassant" and this was his surname at the birth of his son Guy in 1850.[6]

When Maupassant was 11 and his brother Hervé was five, his mother, an independent-minded woman, risked social disgrace to obtain a legal separation from her husband, who was violent towards her.

After the separation, Laure Le Poittevin kept her two sons. With the father's absence, Maupassant's mother became the most influential figure in the young boy's life.[7] She was an exceptionally well-read woman and was very fond of classical literature, particularly Shakespeare. Until the age of thirteen, Guy lived happily with his mother, at Étretat, in the Villa des Verguies, where, between the sea and the luxuriant countryside, he grew very fond of fishing and outdoor activities. At age thirteen, his mother next placed her two sons as day boarders in a private school, the Institution Leroy-Petit, in Rouen—the Institution Robineau of Maupassant's story La Question du Latin—for classical studies.[8] From his early education he retained a marked hostility to religion, and to judge from verses composed around this time he deplored the ecclesiastical atmosphere, its ritual and discipline.[9] Finding the place to be unbearable, he finally got himself expelled in his next-to-last year.[10]

In 1867, as he entered junior high school, Maupassant made acquaintance with Gustave Flaubert at Croisset at the insistence of his mother.[11] Next year, in autumn, he was sent to the Lycée Pierre-Corneille in Rouen[12] where he proved a good scholar indulging in poetry and taking a prominent part in theatricals. In October 1868, at the age of 18, he saved the famous poet Algernon Charles Swinburne from drowning off the coast of Étretat.[13]

The Franco-Prussian War broke out soon after his graduation from college in 1870; he enlisted as a volunteer. In 1871, he left Normandy and moved to Paris where he spent ten years as a clerk in the Navy Department. During this time his only recreation and relaxation was boating on the Seine on Sundays and holidays.

Gustave Flaubert took him under his protection and acted as a kind of literary guardian to him, guiding his debut in journalism and literature. At Flaubert's home, he met Émile Zola and the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, as well as many of the proponents of the realist and naturalist schools. He wrote and played himself in a comedy in 1875 (with the benediction of Flaubert), "À la feuille de rose, maison turque".

In 1878, he was transferred to the Ministry of Public Instruction and became a contributing editor to several leading newspapers such as Le Figaro, Gil Blas, Le Gaulois and l'Écho de Paris. He devoted his spare time to writing novels and short stories.

In 1880 he published what is considered his first masterpiece, "Boule de Suif", which met with instant and tremendous success. Flaubert characterized it as "a masterpiece that will endure." This was Maupassant's first piece of short fiction set during the Franco-Prussian War, and was followed by short stories such as "Deux Amis", "Mother Savage", and "Mademoiselle Fifi".

The decade from 1880 to 1891 was the most fertile period of Maupassant's life. Made famous by his first short story, he worked methodically and produced two or sometimes four volumes annually. His talent and practical business sense made him wealthy.

In 1881 he published his first volume of short stories under the title of La Maison Tellier; it reached its twelfth edition within two years. In 1883 he finished his first novel, Une Vie (translated into English as A Woman's Life), 25,000 copies of which were sold in less than a year. His second novel Bel Ami, which came out in 1885, had thirty-seven printings in four months.

His editor, Havard, commissioned him to write more stories, and Maupassant continued to produce them efficiently and frequently. At this time he wrote what many consider to be his greatest novel, Pierre et Jean.

With a natural aversion to society, he loved retirement, solitude, and meditation. He traveled extensively in Algeria, Italy, England, Brittany, Sicily, Auvergne, and from each voyage brought back a new volume. He cruised on his private yacht Bel-Ami, named after his novel. This life did not prevent him from making friends among the literary celebrities of his day: Alexandre Dumas, fils had a paternal affection for him; at Aix-les-Bains he met Hippolyte Taine and became devoted to the philosopher-historian.

Flaubert continued to act as his literary godfather. His friendship with the Goncourts was of short duration; his frank and practical nature reacted against the ambiance of gossip, scandal, duplicity, and invidious criticism that the two brothers had created around them in the guise of an 18th-century style salon.

Maupassant was one of a fair number of 19th-century Parisians (including Charles Gounod, Alexandre Dumas, fils, and Charles Garnier) who did not care for the Eiffel Tower.[14] He often ate lunch in the restaurant at its base, not out of preference for the food but because it was only there that he could avoid seeing its otherwise unavoidable profile.[15] He and forty-six other Parisian literary and artistic notables attached their names to an elaborately irate letter of protest against the tower's construction, written to the Minister of Public Works.

Maupassant also wrote under several pseudonyms such as Joseph Prunier, Guy de Valmont, and Maufrigneuse (which he used from 1881 to 1885).

In his later years he developed a constant desire for solitude, an obsession for self-preservation, and a fear of death and paranoia of persecution caused by the syphilis he had contracted in his youth. It has been suggested that his brother, Hervé, also suffered from syphilis and the disease may have been congenital.[16] On 2 January 1892, Maupassant tried to commit suicide by cutting his throat, and was committed to the private asylum of Esprit Blanche at Passy, in Paris, where he died 6 July 1893.

Maupassant penned his own epitaph: "I have coveted everything and taken pleasure in nothing." He is buried in Section 26 of the Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.

Significance

Maupassant is considered a father of the modern short story. Literary theorist Kornelije Kvas wrote that along "with Chekhov, Maupassant is the greatest master of the short story in world literature. He is not a naturalist like Zola; to him, physiological processes do not constitute the basis of human actions, although the influence of the environment is manifested in his prose. In many respects, Maupassant’s naturalism is Schopenhauerian anthropological pessimism, as he is often harsh and merciless when it comes to depicting human nature. He owes most to Flaubert, from whom he learned to use a concise and measured style and to establish a distance towards the object of narration."[17] He delighted in clever plotting, and served as a model for Somerset Maugham and O. Henry in this respect. One of his famous short stories, "The Necklace", was imitated with a twist by both Maugham ("Mr Know-All", "A String of Beads"). Henry James's "Paste" adapts another story of his with a similar title, "The Jewels."

Taking his cue from Balzac, Maupassant wrote comfortably in both the high-Realist and fantastic modes; stories and novels such as "L'Héritage" and Bel-Ami aim to recreate Third Republic France in a realistic way, whereas many of the short stories (notably "Le Horla" and "Qui sait?") describe apparently supernatural phenomena.

The supernatural in Maupassant, however, is often implicitly a symptom of the protagonists' troubled minds; Maupassant was fascinated by the burgeoning discipline of psychiatry, and attended the public lectures of Jean-Martin Charcot between 1885 and 1886.[18]

Legacy

Leo Tolstoy used Maupassant as the subject for one of his essays on art: The Works of Guy de Maupassant. His stories are second only to Shakespeare in their inspiration of movie adaptations with films ranging from Stagecoach, Oyuki the Virgin and Masculine Feminine.[19]

Friedrich Nietzsche's autobiography mentions him in the following text:

"I cannot at all conceive in which century of history one could haul together such inquisitive and at the same time delicate psychologists as one can in contemporary Paris: I can name as a sample – for their number is by no means small, ... or to pick out one of the stronger race, a genuine Latin to whom I am particularly attached, Guy de Maupassant."

William Saroyan wrote a short story about Maupassant in his 1971 book, Letters from 74 rue Taitbout or Don't Go But If You Must Say Hello To Everybody.

Isaac Babel wrote a short story about him, “Guy de Maupassant.” It appears in The Collected Stories of Isaac Babel and in the story anthology You’ve Got To Read This: Contemporary American Writers Introduce Stories that Held Them in Awe.

Gene Roddenberry, in an early draft for The Questor Tapes, wrote a scene in which the android Questor employs Maupassant's theory that, "the human female will open her mind to a man to whom she has opened other channels of communications." In the script Questor copulates with a woman to obtain information that she is reluctant to impart. Due to complaints from NBC executives, this part of the script was never filmed.[20]

Michel Drach directed and co-wrote a 1982 French biographical film: Guy de Maupassant. Claude Brasseur stars as the titular character.

Several of Maupassant's short stories, including "La Peur" and "The Necklace", were adapted as episodes of the 1986 Indian anthology television series Katha Sagar.

Bibliography

Short stories

- "A Country Excursion"

- "A Coup d'État"

- "A Coward"

- "A Cremation"

- "Abandoned"

- "The Accent"

- "After"

- "Alexandre"

- "All Over"

- "Allouma"

- "Ampanget"

- "An Old Man"

- "An Adventure in Paris"

- "An Artifice"

- "An Uncomfortable Bed"

- "At Sea"

- "Babette"

- "Bed 29"

- "Belhomme's Beast"

- "Bertha"

- "Beside Schopenhauer's Corpse"

- "Boitelle"

- "Châli"

- "Coco"

- "Confessing"

- "The Accursed Bread"

- "The Adopted Son"

- "The Apparition"

- "The Artist"

- "The Baroness"

- "The Beggar"

- "The Blind Man"

- "Boule de Suif" (Ball of Fat)

- "The Cake"

- "The Capture of Walter Schnaffs"

- "The Child"

- "The Christening"

- "Clair de Lune"

- "Cleopatra in Paris"

- "Clochette"

- "A Cock Crowed"

- "The Colonel's Ideas"

- "The Confession"

- "The Corsican Bandit"

- "The Cripple"

- "A Crisis"

- "The Dead Girl (a.k.a. "Was it a Dream?")"

- "Dead Woman's Secret"

- "The Deaf Mute"

- "Denis"

- "The Devil"

- "The Diamond Necklace"

- "The Diary of a Madman"

- "Discovery"

- "The Dispenser of Holy Water"

- "The Donkey"

- "The Door"

- "The Dowry"

- "Dreams"

- "The Drowned Man"

- "The Drunkard"

- "A Duel"

- "The Effeminates"

- "The Englishman of Etretat"

- "Epiphany"

- "The False Gems"

- "A Family"

- "A Family Affair"

- "Farewell"

- "The Farmer's Wife"

- "Father Matthew"

- "A Father's Confession"

- "The Fishing Hole"

- "Fascination"

- "The Father"

- "Father Milon"

- "Fear"

- "Femme Fatale"

- "The First Snowfall"

- "Florentine"

- "Forbidden Fruit"

- "Forgiveness"

- "Found on a Drowned Man"

- "Friend Joseph"

- "Friend Patience"

- "The Frontier"

- "The Gamekeeper"

- "A Ghost"

- "Ghosts"

- "The Grave"

- "The Graveyard Sisterhood"

- "The Hairpin"

- "The Hand"

- "Growing Old"

- "Happiness"

- "Hautot Senior and Hautot Junior"

- "His Avenger"

- "The Highway Man"

- "The Horla, or Modern Ghosts"

- "The Horrible"

- "The Hostelry"

- "A Humble Drama"

- "The Impolite Sex"

- "In the Country"

- "In the Spring"

- "In the Wood"

- "Indiscretion"

- "The Inn"

- "The Jewelry"

- "Julie Romaine"

- "The Kiss"

- "The Lancer's Wife"

- "Lasting Love"

- "Legend of Mont St. Michel"

- "The Legion of Honour"

- "Lieutenant Lare's Marriage"

- "The Little Cask"

- "Little Louise Roque"

- "A Lively Friend"

- "The Log"

- "Looking Back"

- "The Love of Long Ago"

- "Madame Baptiste"

- "Madame Hermet"

- "Madame Husson's Rosier"

- "Madame Parisse"

- "Madame Tellier's Establishment"

- "Mademoiselle Cocotte"

- "Mademoiselle Fifi"

- "Mademoiselle Pearl"

- "The Maison Tellier"

- "The Magic Couch"

- "Magnetism"

- "Mamma Stirling"

- "The Man with the Pale Eyes"

- "The Marquis de Fumerol"

- "Marroca"

- "Martine"

- "The Mask"

- "A Meeting"

- "A Million" (Un Million)

- "Minuet"

- "Misti"

- "Miss Harriet"

- "The Model"

- "Moiron"

- "Monsieur Parent"

- "Moonlight"

- "The Moribund"

- "Mother and Son"

- "A Mother of Monsters"

- "Mother Sauvage"

- "The Mountain Pool"

- "The Mustache"

- "My Twenty-Five Days"

- "My Uncle Jules"

- "My Uncle Sosthenes"

- "My Wife"

- "The Necklace"

- "A New Year's Gift"

- "The Night: A Nightmare"

- "No Quarter" (French Le père Milon)

- "A Normandy Joke"

- "Old Amable"

- "Old Judas"

- "The Old Man"

- "Old Mongilet"

- "On Horseback"

- "On the River"

- "On a Spring Evening"

- "The Orphan"

- "Our Friends The English"

- "Our Letters"

- "A Parricide"

- "The Parrot"

- "A Passion"

- "The Patron"

- "The Penguin's Rock"

- "The Piece of String"

- "Pierrot"

- "Pierre et Jean"

- "The Port"

- "A Portrait"

- "The Prisoners"

- "The Protector"

- "Queen Hortense"

- "A Queer Night in Paris"

- "The Question of Latin"

- "The Rabbit"

- "A Recollection"

- "Regret"

- "The Rendez-vous"

- "Revenge"

- "The Relic"

- "The Reward"

- "Roger's Method"

- "Roly-Poly" (Boule de Suif)

- "The Rondoli Sisters"

- "Rosalie Prudent"

- "Rose"

- "Rust"

- "A Sale"

- "Saint Anthony"

- "The Shepherd's Leap"

- "The Signal"

- "Simon's Papa"

- "The Snipe"

- "The Son"

- "Solitude"

- "The Story of a Farm Girl"

- "A Stroll"

- "The Spasm"

- "Suicides"

- "Sundays of a Bourgeois"

- "The Terror"

- "The Test"

- "That Costly Ride"

- "That Pig of a Morin"

- "Theodule Sabot's Confession"

- "The Thief"

- "Timbuctoo"

- "Toine"

- "Tombstones"

- "Travelling"

- "A Tress of Hair"

- "The Trip of the Horla"

- "True Story"

- "Two Friends"

- "Two Little Soldiers"

- "The Umbrella"

- "An Uncomfortable Bed"

- "The Unknown"

- "Useless Beauty"

- "A Vagabond"

- "The Vendetta"

- "The Venus of Branzia"

- "En Voyage"

- "Waiter, a "Bock"

- "The Wardrobe"

- "A Wedding Gift"

- "Who Knows?"

- "A Widow"

- "The Will"

- "The Wolf"

- "The Wooden Shoes"

- "The Wreck"

- "The Wrong House"

- "Yvette Samoris"

Novels

- Une Vie (1883)

- Bel-Ami (1885)

- Mont-Oriol (1887)

- Pierre et Jean (1888)

- Fort comme la mort (1889)

- Notre Cœur (1890)

- L'Angelus (1910) - unfinished

- L'Âmé Éntrangère (1910) - unfinished

Short-story collections

- Les Soirées de Médan (with Zola, Huysmans et al. Contains Boule de Suif by Maupassant) (1880)

- La Maison Tellier (1881)

- Mademoiselle Fifi (1883)

- Contes de la Bécasse (1883)

- Miss Harriet (1884)

- Les Sœurs Rondoli (1884)

- Clair de lune (1884) (contains "Les Bijoux")

- Yvette (1884)

- Contes du jour et de la nuit (1885) (contains "La Parure" or "The Necklace")

- Monsieur Parent (1886)

- La Petite Roque (1886)

- Toine (1886)

- Le Horla (1887)

- Le Rosier de Madame Husson (1888)

- La Main gauche (1889)

- L'Inutile Beauté (1890)

Travel writing

- Au soleil (1884)

- Sur l'eau (1888)

- La Vie errante (1890)

Poetry

- Des Vers (1880)[21] containing Nuit de Neige

References

- "Maupassant, Guy de". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Maupassant, Guy de". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Maupassant". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- "Maupassant". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Maupassant". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Alain-Claude Gicquel, Maupassant, tel un météore, Le Castor Astral, 1993, p. 12

- "Guy de Maupassant Biography". enotes. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- Maupassant, Choix de Contes, Cambridge, p. viii, 1945

- de Maupassant, Guy (1984). Le Horla et autres contes d'angoisse (in French) (2006 ed.). Paris: Flammarion. p. 233. ISBN 978-2-0807-1300-1.

- "Biographie de Guy de Maupassant". @lalettre.com. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Maupassant's Apprenticeship with Flaubert".

- "Lycée Pierre Corneille de Rouen - History". Lgcorneille-lyc.spip.ac-rouen.fr. 19 April 1944. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Clyde K. Hyder, Algernon Swinburne: The Critical Heritage, 1995, p. 185

- "The Tower of Babel - Criticism of Eiffel Tower". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013.

- Barthes, Roland. The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies. Tr. Howard, Richard. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20982-4. Page 1.

- "Remembering Maupassant | Arts and Entertainment | BBC World Service". Bbc.co.uk. 9 August 2000. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Kvas, Kornelije (2019). The Boundaries of Realism in World Literature. Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Lexington Books. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-7936-0910-6.

- Pierre Bayard, Maupassant, juste avant Freud (Paris: Minuit, 1998)

- Richard Brody (26 October 2015). "The Writer Who Sparks the Finest Movie Adaptations". The New Yorker. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- [Quoted from the track "The Questor Affair" from the album Inside Star Trek.]

- The Tales of Maupassant. New York: Heritage Press. 1964.

Further reading

- Abamine, E. P. "German-French Sexual Encounters of the Franco-Prussian War Period in the Fiction of Guy de Maupassant." CLA Journal 32.3 (1989): 323–334. online

- Dugan, John Raymond. Illusion and reality: a study of descriptive techniques in the works of Guy de Maupassant (Walter de Gruyter, 2014).

- Fagley, Robert. Bachelors, Bastards, and Nomadic Masculinity: Illegitimacy in Guy de Maupassant and André Gide (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014) online.

- Harris, Trevor A. Le V. Maupassant in the Hall of Mirrors: Ironies of Repetition in the Work of Guy de Maupassant (Springer, 1990).

- Rougle, Charles. "Art and the Artist in Babel's" Guy de Maupassant"." The Russian Review 48.2 (1989): 171-180. online

- Sattar, Atia. "Certain Madness: Guy de Maupassant and Hypnotism." Configurations 19.2 (2011): 213–241. regarding both versions of his horror story “The Horla” (1886/1887). online

- Stivale, Charles J. The art of rupture: narrative desire and duplicity in the tales of Guy de Maupassant (University of Michigan Press, 1994).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Guy de Maupassant |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guy de Maupassant. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Guy de Maupassant |

- Maupassantiana, a French scholar's website on Maupassant and his works

- Works by Guy de Maupassant at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Guy de Maupassant at Internet Archive

- Works by Guy de Maupassant at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Université McGill: le roman selon les romanciers Recensement et analyse des écrits non romanesques de Guy de Maupassant

- Works by Guy de Maupassant at Online Literature (HTML)

- Works by Guy de Maupassant in Ebooks (in French)

- Works by Guy de Maupassant (text, concordances and frequency list)

- Petri Liukkonen. "Guy de Maupassant". Books and Writers

- Oeuvres de Maupassant, à Athena (in French)