Charles Gounod

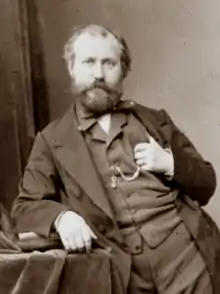

Charles-François Gounod (/ɡuːˈnoʊ/; French: [ʃaʁl fʁɑ̃swa ɡuno]; 17 June 1818 – 18 October 1893), usually known as Charles Gounod, was a French composer. He wrote twelve operas, of which the most popular has always been Faust (1859); his Roméo et Juliette (1867) also remains in the international repertory. He composed a large amount of church music, many songs, and popular short pieces including his Ave Maria (an elaboration of a Bach piece), and Funeral March of a Marionette.

Born in Paris into an artistic and musical family Gounod was a student at the Conservatoire de Paris and won France's most prestigious musical prize, the Prix de Rome. His studies took him to Italy, Austria and then Prussia, where he met Felix Mendelssohn, whose advocacy of the music of Bach was an early influence on him. He was deeply religious, and after his return to Paris, he briefly considered becoming a priest. He composed prolifically, writing church music, songs, orchestral music and operas.

Gounod's career was disrupted by the Franco-Prussian War. He moved to England with his family for refuge from the Prussian advance on Paris in 1870. After peace was restored in 1871 his family returned to Paris but he remained in London, living in the house of an amateur singer, Georgina Weldon, who became the controlling figure in his life. After nearly three years he broke away from her and returned to his family in France. His absence, and the appearance of younger French composers, meant that he was no longer at the forefront of French musical life; although he remained a respected figure he was regarded as old-fashioned during his later years, and operatic success eluded him. He died at his house in Saint-Cloud, near Paris at the age of 75.

Few of Gounod's works remain in the regular international repertoire, but his influence on later French composers was considerable. In his music there is a strand of romantic sentiment that is continued in the operas of Jules Massenet and others; there is also a strand of classical restraint and elegance that influenced Gabriel Fauré. Claude Debussy wrote that Gounod represented the essential French sensibility of his time.

Life and career

Early years

Gounod was born on 17 June 1818 in the Latin Quarter of Paris, the second son of François Louis Gounod (1758–1823) and his wife Victoire, née Lemachois (1780–1858).[1] François was a painter and art teacher; Victoire was a talented pianist, who had given lessons in her early years.[2] The elder son, Louis Urbain (1807–1850), became a successful architect.[3] Shortly after Charles's birth François was appointed official artist to the Duc de Berry, a member of the royal family, and the Gounods' home in Charles's early years was at the Palace of Versailles, where they were allotted an apartment.[4]

After François's death in 1823, Victoire supported the family by returning to her old occupation as a piano teacher.[5] The young Gounod attended a succession of schools in Paris, ending with the Lycée Saint-Louis.[6] He was a capable scholar, excelling in Latin and Greek.[7] His mother, the daughter of a magistrate, hoped Gounod would pursue a secure career as a lawyer,[8] but his interests were in the arts: he was a talented painter and outstandingly musical.[1][9] Early influences on him, in addition to his mother's musical instruction, were operas, seen at the Théâtre-Italien: Rossini's Otello and Mozart's Don Giovanni. Of a performance of the latter in 1835 he later recalled, "I sat in one long rapture from the beginning of the opera to its close".[10] Later in the same year he heard performances of Beethoven's Pastoral and Choral symphonies, which added "fresh impulse to my musical ardour".[11]

While still at school Gounod studied music privately with Anton Reicha – who had been a friend of Beethoven and was described by a contemporary as "the greatest teacher then living"[12] – and in 1836 he was admitted to the Conservatoire de Paris.[1] There he studied composition with Fromental Halévy, Henri Berton, Jean Lesueur and Ferdinando Paer and piano with Pierre Zimmerman.[13] His various teachers made only a moderate impression on Gounod's musical development, but during his time at the Conservatoire he encountered Hector Berlioz. He later said that Berlioz and his music were among the greatest emotional influences of his youth.[14] In 1838, after Lesueur's death, some of his former students collaborated to compose a commemorative mass; the Agnus Dei was allocated to Gounod. Berlioz said of it, "The Agnus, for three solo voices with chorus, by M. Gounod, the youngest of Lesueur's pupils, is beautiful – very beautiful. Everything in it is novel and distinguished – melody, modulation, harmony. In this piece M. Gounod has given proof that we may expect everything of him".[15]

Prix de Rome

In 1839, at his third attempt, Gounod won France's most prestigious musical prize, the Prix de Rome for composition, for his cantata Fernand.[16][n 1] In doing so he was surpassing his father: François had taken the second prize in the Prix de Rome for painting in 1783.[1] The Prix brought the winner two years' subsidised study at the French Institute in Rome and a further year in Austria and Germany. For Gounod this not only launched his musical career, but made impressions on him both spiritually and musically that stayed with him for the rest of his life.[14] In the view of the musicologist Timothy Flynn, the Prix, with its time in Italy, Austria and Germany, was "arguably the most significant event in [Gounod's] career".[14] He was fortunate that the director of the institute was the painter Dominique Ingres, who had known François Gounod well and took his old friend's son under his wing.[18][n 2]

Among the artistic notables the composer met in Rome were the singer Pauline Viardot and the pianist Fanny Hensel, sister of Felix Mendelssohn.[20] Viardot became of great help to Gounod in his later career, and through Hensel he got to know the music not only of her brother but also of J. S. Bach, whose music, long neglected, Mendelssohn was enthusiastically reviving.[21] Gounod was also introduced to "various masterpieces of German music which I had never heard before".[22] While in Italy, Gounod read Goethe's Faust, and began sketching music for an operatic setting, which came to fruition over the next twenty years.[14] Other music he composed during his three years' scholarship included some of his best-known songs, such as "Où voulez-vous aller?" (1839), "Le Soir" (1840–1842) and "Venise" (1842), and a setting of the Mass ordinary, which was performed at the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome.[14][23]

In Rome, Gounod found his strong religious impulses increased under the influence of the Dominican preacher Henri-Dominique Lacordaire and he was inspired by paintings in the city's churches.[24] Unlike Berlioz, who had been unimpressed by the visual arts of Rome when he was at the Institute ten years earlier, Gounod was awed by the work of Michelangelo.[25] He also came to know and revere the sacred music of Palestrina, which he described as a musical translation of Michelangelo's art.[14][n 3] The music of some of his own Italian contemporaries did not appeal to him. He severely criticised operas by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante, composers he described as merely "vines twisted around the great Rossinian trunk, without its vitality and majesty" and lacking Rossini's spontaneous melodic genius.[1]

For the last year of his Prix de Rome scholarship, Gounod moved to Austria and Germany. At the Court Opera in Vienna he heard The Magic Flute for the first time, and his letters record his joy at living in the city where Mozart and Beethoven had worked.[27] Count Ferdinand von Stockhammer, a leading patron of the arts in Vienna, arranged for Gounod's setting of the Requiem Mass to be performed.[28] It was warmly received, and its success led Stockhammer to commission a second Mass from the composer.[29]

From Vienna, Gounod moved on to Prussia. He renewed his acquaintance with Fanny Hensel in Berlin and then went on to Leipzig to meet her brother. At their first encounter Mendelssohn greeted him, "So you're the madman my sister has told me about",[n 4] but he devoted four days to entertaining the young man and gave him much encouragement.[30] He arranged a special concert of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra so that his guest might hear the Scottish Symphony, and played him some of the works of Bach on the organ of the Thomaskirche.[31] Reciprocating, Gounod played the Dies Irae from his Viennese Requiem, and was gratified when Mendelssohn said of one passage that it was worthy to be signed by Luigi Cherubini. Gounod commented, "Words like this from such a master are a true honour and one wears them with more pride than many a ribbon".[n 5]

Rising reputation

Gounod arrived home in Paris in May 1843. He took up a post, which his mother had helped to secure, as chapel master of the church of the Missions étrangères. For a winner of the Prix de Rome it was not a distinguished position. The organ of the church was poor, and the choir consisted of two basses, a tenor and a choirboy.[32] To compound Gounod's difficulties, the regular congregation was hostile to his attempts to improve the music of the church.[33] He expressed his views to a colleague:

Despite his generally affable and compliant nature Gounod remained adamant; he gradually won his parishioners over, and served for most of the five-year term he had agreed to.[35] During this period Gounod's religious feelings became increasingly strong. He was reunited with a childhood friend, now a priest, Charles Gay, and for a time he himself felt drawn to holy orders.[29] In 1847 he began to study theology and philosophy at the seminary of St Sulpice, but before long his secular side asserted itself. Doubting his capacity for celibacy, he decided not to seek ordination and continued with his career as a musician.[33] He later recalled:

The outset of Gounod's theatrical career was greatly helped by his reacquaintance with Pauline Viardot in Paris in 1849. Viardot, then at the peak of her fame, was able to secure for him a commission for a full-length opera. In this Gounod was exceptionally fortunate: a novice composer in the 1840s would usually, at the most, be asked to write a one-act curtain raiser.[37] Gounod and his librettist, Emile Augier, created Sapho, drawing on Ancient Greek legend. It was intended as a departure from the three genres of opera then prevalent in Paris – Italian opera, grand opera and opéra comique. It later came to be regarded as the first of a new type, opéra lyrique, but at the time it was thought by some to be a throwback to the operas of Gluck, written sixty or seventy years earlier.[38] After difficulties with the censor, who found the text politically suspect and too erotic, Sapho was given at the Paris Opéra at the Salle Le Peletier on 16 April 1851.[39] It was reviewed by Berlioz in his capacity as a music critic; he found some parts "extremely beautiful … the highest poetic level of drama", and others "hideous, unbearable, horrible".[40] It did not draw the public and closed after nine performances.[40] The opera received a single performance at the Royal Opera House in London later in the same year, with Viardot again in the title role. The music received more praise than the libretto, and the performers received more than either, but The Morning Post recorded, "The opera, we regret to say, was received very coldly".[41]

In April 1851 Gounod married Anna Zimmerman (1829–1907), daughter of his former piano professor at the Conservatoire. The marriage led to a breach with Viardot; the Zimmermanns refused to have anything to do with her, for reasons that are not clear. Gounod's biographer Steven Huebner refers to rumours about a liaison between the singer and composer, but adds that "the real story remains murky".[1] Gounod was appointed superintendent of instruction in singing to the communal schools in the city of Paris, and from 1852 to 1860 he was director of a prominent choral society, the Orphéon de la Ville de Paris.[42] He also frequently stood in for his elderly and often ill father-in-law, giving music lessons to private pupils. One of them, Georges Bizet, found Gounod's teaching inspiring, praised "his warm and paternal interest" and remained a lifelong admirer.[43][n 6]

Despite the brevity of Sapho's run, the piece advanced Gounod's reputation, and the Comédie-Française commissioned him to write incidental music for François Ponsard's five-act verse tragedy Ulysse (1852), based on the Odyssey. The score included twelve choruses as well as orchestral interludes. It was not a successful production: Ponsard's play was not well received, and the audience at the Comédie-Française had little interest in music.[46] During the 1850s Gounod composed his two symphonies for full orchestra and one of his best-known religious works, the Messe solennelle en l'honneur de Sainte-Cécile. It was written for the St Cecilia's day celebrations of 1855 at Saint-Eustache, and in Flynn's view demonstrates Gounod's success in "blending the operatic style with church music – a task at which many of his colleagues tried and failed".[29]

As well as church and concert music, Gounod was composing operas, beginning with La Nonne sanglante (The Bloody Nun, 1854), a melodramatic ghost story with a libretto that Berlioz had tried and failed to set, and that Auber, Meyerbeer, Verdi and others had rejected.[47] The librettists, Eugène Scribe and Germain Delavigne, reworked the text for Gounod and the piece opened at the Opéra on 18 October 1854.[48] The critics derided the libretto but praised the music and production; the work was doing well at the box-office until it fell victim to musical politics. The director of the Opéra, Nestor Roqueplan, was supplanted by his enemy, François-Louis Crosnier, who described La Nonne sanglante as "filth" and shut the production down after its eleventh performance.[49]

Operatic successes and failures

In January 1856 Gounod was appointed a knight of the Legion of Honour.[50] In June of that year he and his wife had the first of their two children, a son Jean (1856–1935).[51] (Their daughter Jeanne (1863–1945) was born seven years later.[52]) In 1858 Gounod composed his next opera, Le Médecin malgré lui. With a good libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, faithful to the Molière comedy on which it is based, it gained excellent reviews,[53] but its good reception was overshadowed for Gounod by the death of his mother the day after the premiere.[54][55] At the time an initial run of 100 performances was considered a success;[56] Le Médecin malgré lui achieved that and was revived in Paris and elsewhere during the rest of the 19th century and into the 20th.[57] In 1893 the British Musical Times praised its "irresistible gaiety".[7] Huebner comments that the opera does not deserve the relative neglect into which it has since fallen.[1]

With Barbier and Carré, Gounod turned from French comedy to German legend for Faust. The three had worked on the piece in 1856, but it had to be shelved to avoid clashing with a rival (non-operatic) Faust at another theatre. Returning to it in 1858 Gounod completed the score, rehearsals began towards the end of the year and the opera opened at the Théâtre-Lyrique in March 1859.[1] One critic reported that it was presented "under circumstances of uncommon excitement and expectation";[58] another praised the work but doubted if it would have enough popular appeal to be a commercial triumph.[59] The composer later recalled that the opera "did not strike the public very much at first",[60] but after some revision and with a good deal of vigorous promotion by Gounod's publisher, Antoine de Choudens, it became an international success. There were productions in Vienna in 1861, and in Berlin, London and New York in 1863.[61] Faust has remained Gounod's most popular opera and one of the staples of the operatic repertoire.[62]

Over the next eight years Gounod composed five more operas, all with Barbier or Carré or both. Philémon et Baucis (1860) and La Colombe (The Dove, 1860) were opéras comiques based on stories by Jean de La Fontaine. The first was an attempt to take advantage of a vogue for mildly satirical comedies in mythological dress started by Jacques Offenbach with Orphée aux enfers (1858).[63] The opera had originally been intended for the theatre at Baden-Baden,[64] but Offenbach and his authors expanded it for its eventual first performance, in Paris at the Théâtre Lyrique.[64] La Colombe, also written for Baden-Baden, was premiered there and later expanded for its first Paris production (1886).

After these two moderate successes,[65] Gounod had an outright failure, La Reine de Saba (1862), a grand opera with an exotic setting. The piece was lavishly mounted, and the premiere was attended by the Emperor Napoleon III and the Empress Eugénie,[66] but the reviews were damning and the run finished after fifteen performances.[67][n 7] The composer, depressed by the failure, sought comfort in a long trip to Rome with his family. The city enchanted him as much as ever: in Huebner's words "renewed exposure to Rome's close entwining of Christianity and classical culture energized him for the travails of his career back in Paris".[1][67]

Gounod's next opera was Mireille (1864), a five-act tragedy in a Provençal peasant setting. Gounod travelled to Provence to absorb the local atmosphere of the various settings of the work and to meet the author of the original story, Frédéric Mistral.[69] Some critics have seen the piece as a forerunner of verismo opera, although one that emphasises elegance over sensationalism.[70] The opera was not a great success at first; there were strong objections from some quarters that Gounod had given full tragic status to a mere farmer's daughter.[71] After some revision it became popular in France, and remained in the regular opéra comique repertoire into the 20th century.[69]

In 1866 Gounod was elected to the Académie des Beaux-Arts and was promoted within the Legion of Honour.[72] During the 1860s his non-operatic works included a Mass (1862), a Stabat Mater (1867), twenty shorter pieces of liturgical or other religious music, two cantatas – one religious, one secular – and a Marche pontificale for the anniversary of the coronation of Pius IX (1869), later adopted as the official anthem of the Vatican City.[1]

Gounod's last opera of the 1860s was Roméo et Juliette (1867), with a libretto that follows Shakespeare's play fairly closely.[71][n 8] The piece was a success from the outset, with box-office receipts boosted by the large number of visitors to Paris for the Exposition Universelle. Within a year of the premiere it was staged in major opera houses in continental Europe, Britain and the US. Other than Faust it remains the only Gounod opera to be frequently staged internationally.[73][74]

London

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Gounod moved with his family from their home in Saint-Cloud, outside Paris, first to the countryside near Dieppe and then to England. The house in Saint-Cloud was wrecked by the advancing Prussians in the build-up to the Siege of Paris.[n 9] To earn a living in London, Gounod wrote music for a British publisher; in Victorian Britain there was a great demand for religious and quasi-religious drawing room ballads, and he was happy to provide them.[76]

Gounod accepted an invitation from the organising committee of the Annual International Exhibition to write a choral piece for its grand opening at the Royal Albert Hall on 1 May 1871. As a result of its favourable reception he was appointed director of the new Royal Albert Hall Choral Society, which, with Queen Victoria's approval, was subsequently renamed the Royal Choral Society.[77][78] He also conducted orchestral concerts for the Philharmonic Society and at the Crystal Palace, St James's Hall and other venues.[79][n 10] Proponents of English music complained that Gounod neglected native composers in his concerts,[81] but his own music was popular and widely praised. The music critic of The Times, J. W. Davison, rarely pleased by modern music, was not an admirer,[82] but Henry Chorley of The Athenaeum was an enthusiastic supporter,[83] and writers in The Musical World, The Standard, The Pall Mall Gazette and The Morning Post called Gounod a great composer.[84]

In February 1871, Julius Benedict, the director of the Philharmonic Society, introduced Gounod to a singer and music teacher called Georgina Weldon.[85] She quickly became a dominant influence in Gounod's professional and personal life. There was much inconclusive conjecture about the nature of their relationship. Once peace was restored in France during 1871, Anna Gounod returned home with her mother and children, but Gounod stayed on in London, living in the Weldons' house.[86] Weldon introduced him to competitive business practices with publishers, negotiating substantial royalties, but eventually pushed such matters too far and involved him in litigation brought by his publisher, which the composer lost.[1]

Gounod lived in the Weldons' household for nearly three years. The French newspapers speculated about his motives for remaining in London; they speculated the more when it was suggested that he had declined the French President's invitation to return and succeed Auber as director of the Conservatoire.[86] In early 1874 his relations with Davison of The Times, never cordial, descended into personal hostility.[87] The pressures on him in England and the comments about him in France brought Gounod to a state of nervous collapse, and in May 1874 his friend Gaston de Beaucourt came to London and took him back home to Paris.[88] Weldon was furious when she discovered that Gounod had left, and she made many difficulties for him later, including holding on to manuscripts he had left at her house and publishing a tendentious and self-justifying account of their association. She later brought a lawsuit against him which effectively prevented him from coming back to Britain after May 1885.[89][n 11]

Later years

The musical scene in France had altered considerably during Gounod's absence. After the death of Berlioz in 1869, Gounod had been generally regarded as France's leading composer.[92] He returned to a France in which, though still well respected, he was no longer in the vanguard of French music.[76] A rising generation, including members of the new Société Nationale de Musique such as Bizet, Emmanuel Chabrier, Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet, was establishing itself.[93] He was not embittered, and was well disposed to younger composers, even when he did not enjoy their works.[94] Of the later generation he was most impressed by Camille Saint-Saëns, seventeen years his junior, whom he is said to have dubbed "the French Beethoven".[95]

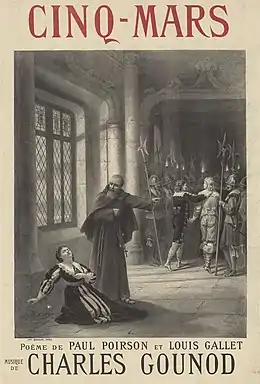

Resuming operatic composition, Gounod finished Polyeucte, on which he had been working in London, and during 1876 composed Cinq-Mars, a four-act historical drama set in the time of Cardinal Richelieu.[96] The latter was staged first at the Opéra-Comique in April 1877, and had a mediocre run of 56 performances.[97] Polyeucte, a religious subject close to the composer's heart, did worse when it was given at the Opéra the following year. In the words of Gounod's biographer James Harding, "After Polyeucte had been martyred on twenty-nine occasions the box-office ruled that enough was enough. He was never resuscitated."[98]

The last of Gounod's operas, Le Tribut de Zamora (1881), ran for 34 nights,[99] and in 1884 he made a revision of Sapho, which lasted for 30 performances at the Opéra.[100] He reworked the role of Glycère, the deceitful villainess of the piece, with the image of Weldon in his mind: "I dreamt of the model … who was terrifying in satanic ugliness"[101] Throughout these disappointments Faust continued to attract the public, and in November 1888 Gounod conducted the 500th performance at the Opéra.[n 12]

_by_Nadar.jpg.webp)

Away from opera Gounod wrote the large-scale Messe du Sacré-Coeur de Jésus in 1876 and ten other masses between then and 1893.[103] His greatest popular successes in his later career were religious works, the two large oratorios La Rédemption (1882) and Mors et vita (1885), both composed for and premiered at the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival in England.[104] The two were enthusiastically taken up by the British public and on the continent, and in their day were widely ranked with the oratorios of Handel and Mendelssohn.[105] The Philharmonic Society in London unsuccessfully sought to commission a symphony from the composer in 1885 (the commission eventually went to Saint-Saëns);[106] fragments of a third symphony exist from late in Gounod's career, but are thought to date from a few years later.[107]

Gounod's last years were lived at Saint-Cloud, composing sacred music and writing his memoirs and essays. On 15 October 1893, after returning home from playing the organ for Mass at his local church, he suffered a stroke while working on a setting of the Requiem in memory of his grandson Maurice, who had died in infancy. After being in a coma for three days Gounod died on 18 October, at the age of 75.[108]

A state funeral was held at L'église de la Madeleine, Paris, on 27 October 1893. Among the pallbearers were Ambroise Thomas, Victorien Sardou and the future French President Raymond Poincaré.[n 13] Fauré conducted the music, which at Gounod's wish was entirely vocal, with no organ or orchestral accompaniment. After the service, Gounod's remains were taken in procession to the Cimetière d'Auteuil, near Saint-Cloud, where they were interred in the family vault.[109]

Music

Gounod is best known for his operas – in particular Faust. Celebrated during his lifetime, Gounod's religious music became unfashionable in the 20th century and little of it is regularly heard. His songs, an important influence on later French composers, are less neglected, although only a few are well known.[1] Michael Kennedy writes that Gounod's music has "considerable melodic charm and felicity, with admirable orchestration". He adds that Gounod was "not really a master of the large and imposing forms, in this way perhaps being a French parallel to Sullivan".[110] There is wide agreement among commentators that he was at his finest more often in the earlier decades of his career than later. Robert Orledge judges that in the 1850s and 1860s Gounod introduced to French opera a combination of "tender, lyrical charm, consummate craftsmanship, and genuine musical characterization", but his later works tend to "sentimentality and banality ... in his quest for inspired simplicity".[111]

Cooper writes that as Gounod grew older he began to suffer from "what might be described as the same cher grand maître complex as infected Hugo and Tennyson".[n 14] Huebner observes that the fact that Gounod's reputation began to wane even during his lifetime does not detract from his place among the most respected and prolific composers in France during the second half of the 19th century.[1]

Operas

Gounod wrote twelve operas, in a variety of the genres then prevailing in France. Sapho (1851) was an early example of opéra lyrique, smaller-scale and more intimate than grand opera but through-composed, without the spoken dialogue of opéra comique. Berlioz wrote of it, "Most of the choruses I found imposing and simple in accent; the whole third act seemed to me very beautiful ... But the quartet in the first act, the duet and trio in the second, where the passions of the principal characters break out with such force, absolutely revolted me".[40] A more recent reviewer remarks on Gounod's "genuine talent for music-drama ... exercised in the Quartet of Act 1 where each character has an independent part, making effective counterpoint in dramatic as well as musical terms".[112] Gounod revised the work in 1858 and again, more radically, in 1884, but it was never a success. The one fairly well known number from the score, Sapho's "O ma lyre immortelle", is a reworking of a song he had composed in 1841.[113]

La Nonne sanglante (1854), a work on a larger scale than Sapho, suffers from a libretto that Huebner describes as an "unhappy blend of historico-political grand opera and the supernatural". He observes that in the traditions of grand opera it features processions, ballets, large ensemble numbers, and "a plot where the love interest is set against a more or less clearly drawn historical backdrop". Announcing a rare revival of the work in 2018, the Opéra-Comique described the score as "refined, sombre, and labyrinthine". A reviewer praised its "verve and imagination ... colourful and percussive music, well adapted to evoke the horror of the situations ... quite voluptuous in the arias (in a score that one can nevertheless find rather academic in parts)".[114][n 15]

Cooper classes Le Médecin malgré lui (1858) as one of Gounod's finest works, "witty, quick-moving and full of life".[115] In complete contrast to its predecessor, it is a three-act comedy, regarded as a masterpiece by Richard Strauss and Igor Stravinsky.[116] Cooper says of the score that Gounod seems to have learned more from Mozart than from Rossini or Auber, and to have "divined by instinct the great comic possibilities of what passed at that time for a ferociously 'learned' style, namely counterpoint."[115] The piece held its place in the repertory during the latter part of the 19th century, but by the time Serge Diaghilev revived it in 1924 Gounod was out of fashion. In Stravinsky's words, "[Diaghilev's] dream of a Gounod 'revival' failed in the face of an indifferent and snobbish public who did not dare applaud the music of a composer not accepted by the avant-garde".[117] For his revival Diaghilev commissioned Erik Satie to compose recitatives to replace the original spoken dialogue, and that version is sometimes used in the occasional modern productions of the piece, such as that by Laurent Pelly at the Grand Théâtre de Genève in 2016.[116]

Faust (1859) appealed to the public not only because of its tunefulness but also for its naturalness.[1][118] In contrast with grand operas by Gounod's older contemporaries, such as Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots or Rossini's William Tell, Faust in its original 1859 form tells its story without spectacular ballets, opulent staging, grand orchestral effects or conventionally theatrical emotion.[118] "The charm of Faust lay in its naturalness, its simplicity, the sincerity and directness of its emotional appeal" (Cooper).[118] The authors labelled Faust "a lyric drama", and some commentators find the lyrical scenes stronger than the dramatic and supernatural ones.[1][118] Among the best known numbers from the piece are Marguerite's "Jewel" song, the Soldiers' Chorus, Faust's aria "Salut! Demeure chaste et pure" and Méphistophélès' "Le Veau d’or" and Sérénade.[119] Another popular song is Valentin's "Avant de quitter ces lieux", which Gounod, rather reluctantly, wrote for the first London production, where the star baritone required an extra number.[62] Among the popular numbers from the score is the ballet music, written when the Opéra – where a ballet interlude was mandatory – took over presentation of the work in 1869. The ballet makes full use of the Opéra's large orchestral resources; it is now frequently omitted in live performances, particularly in productions outside France,[120] but the ballet suite became a popular concert item, independent of the opera.[n 16] The recitatives generally used instead of the original spoken dialogue were composed by Gounod in an early revision of the score.[120]

Writing of Philémon et Baucis, Huebner comments that there is little dramatic music in the score and that most of the numbers are "purely decorative accretions to the spoken dialogue". For the 1876 revival at the Opéra-Comique, which established the work in the repertory there until the Second World War, Gounod reduced it to two acts. For a revival by Diaghilev in 1924, the young Francis Poulenc composed recitatives to replace the spoken dialogue.[63] The music critic Andrew Clements writes of La Colombe that it is not a profound work, but is "well filled with the kind of ingratiating tunes that Gounod could turn out so effectively".[122] Although La Reine de Saba was a failure, it contains three numbers that gained moderate popularity: the Queen's big aria‚ "Plus grand dans son obscurité", King Solomon's "Sous les pieds d'une femme" and the tenor solo "Faiblesse de la race humaine".[123]

Mireille (1865) was a moderate success, and although it did not emulate Faust in becoming an international hit, it remained popular in France into the 20th century. The most famous number, the waltz-song "O légère hirondelle", a favourite display piece for many coloratura sopranos, was written to order for the prima-donna of the Théâtre Lyrique a year after the premiere. Another popular number is Ourrias's swaggering "Si les filles d'Arles" described by the critic Patrick O'Connor as an attempt by the composer to repeat the success of Méphistophélès' Veau d'or from Faust.[124] Gounod revised the work, even giving it a happy ending, but in the 1930s Reynaldo Hahn and Henri Büsser prepared a new edition for the Opéra-Comique, restoring the work to its original tragic five acts.[124]

Gounod's last successful opera was Roméo et Juliette (1867). Gustav Kobbé wrote five decades later that the work had always been more highly regarded in France than elsewhere. He said that it had never been popular in England except as a vehicle for Adelina Patti and then Nellie Melba, and that in New York it had only featured regularly at the Metropolitan Opera when it was under the control of Maurice Grau in the late 19th-century.[125] Some reviewers thought it inappropriate that Juliet was allotted a waltz song ("Je veux vivre, dans ce rêve"),[126] but Romeo's "Ah! levè-toi, soleil" was judged one of Gounod's finest tenor arias.[125] Although never as popular as Faust, Roméo et Juliette continues to hold the stage internationally.[74] Gounod had no further success with new operas. His three attempts, Cinq-Mars (1877), Polyeucte (1888), and Le Tribut de Zamora (1881), were all taken off after brief runs, and have seldom been seen since.[1]

Orchestral and chamber music

The two symphonies, in D major and E-flat major, cannot be precisely dated. The first was completed at some time before 1855 and the second by 1856.[127] Like many other composers of the mid-19th-century Gounod found Beethoven's shadow daunting when contemplating the composition of a symphony, and there was even a feeling among the French musical public that composers could write operas or symphonies but not both.[127][128] The influence of Beethoven is apparent in Gounod's two symphonies, and the musical scholar Roger Nichols and the composer's biographer Gérard Condé also find a debt to Mendelssohn's Italian Symphony in the slow movement of the First.[127] Gounod's sometime pupil Bizet took the First as his model for his own Symphony in C (1855). Late in life Gounod started but did not complete a Third Symphony. A complete slow movement and much of a first movement survive.[107] Other orchestral works include the Funeral March of a Marionette (1879), an orchestration of an 1872 solo piano piece.[1]

The Petite Symphonie (1885), written for nine wind instruments, follows the classical, four-movement pattern, with a slow introduction to the sonata form first movement. The commentator Diether Stepphun refers to its "cheerfully contemplative and gallant wit, with all the experience of human and musical maturity".[129] Gounod's Ave Maria gained considerable popularity. It consists of a descant superimposed over a version of the first prelude of Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier. In its original form it is for violin with piano; the words of the Hail Mary were added to the melody later.[1]

Religious music

Gounod's output of liturgical and other religious music was prolific, including 23 masses, more than 40 other Latin liturgical settings, more than 50 religious songs and part-songs, and seven cantatas or oratorios.[1] During his lifetime his religious music was regarded in many quarters more highly than his most popular operas. Saint-Saëns wrote, "When, in the far-distant future, the operas of Gounod shall have been received into the dusty sanctuary of the libraries, the Mass of St Cecilia, the Redemption, and Mors et Vita, will still endure".[130] In the 20th century views changed considerably. In 1916 Gustave Chouquet and Adolphe Jullien wrote of "a monotony and heaviness which must weary the best-disposed audience".[131] In 1918, in a centenary tribute to Gounod, Julien Tiersot described La Rédemption and Mors et Vita as "imbued with pure and elevated lyricism",[132] but this view did not prevail. Other critics have referred to "the ooze of the erotic priest" and called the oratorios "the height of nineteenth-century hypocritical piety".[133]

Orledge judges the early masses as the best of Gounod's religious music. He comments that the composer moved away from "Palestrinian austerity" towards "a more fluid, operatic style" in his Messe solennelle de Sainte Cécile (1855).[n 17] He comments that in general Gounod's work in the 1860s "became more Italianate, while retaining its French attributes of precision, taste, and elegance".[111]

Songs

Gounod's songs are by far the most numerous of his compositions: he wrote more than a hundred French secular songs and thirty more in English or Italian for the British market.[1] The songs come from every stage of his career, but most of the best are generally considered to be from the earlier years. Maurice Ravel called Gounod "the true founder of the mélodie in France".[23] The pianist and musical scholar Graham Johnson, quoting this, adds that although Berlioz might be thought to have a claim to that title, it was Gounod who brought the mélodie widespread popularity in France:

Johnson adds that Gounod brought to the mélodie "those qualities of elegance, ingenuity, sensibilité, and a concern for literature which together constitute the classic qualities of French song" in mélodies that display the composer's "melodic genius, his talent for creating long flowing lines (only surpassed by Fauré), and his instinct for the harmonic juste".[135]

From his earliest period, during and just after his time as a Prix de Rome student, Gounod's songs include some of his best, in the view of both Huebner and Johnson.[1][136] Examples include "Où voulez-vous aller?" (words by Gauthier, 1839) – which challenged comparison with Berlioz, who had already set the poem in his Les Nuits d'été[n 18] – and "Venice" (Musset), 1842, described by Johnson as "astonishingly evocative with its turbulent interludes painting that city's ability both to intoxicate and disturb".[136] Other early songs such as "Le vallon" and "Le soir" (both to words by Lamartine, c. 1840) demonstrate Gounod's ability to cope with large-scale Romantic verse.[136]

The songs of Gounod's middle and later years are in the main judged less impressive.[135] Johnson compares Gounod with Mendelssohn in terms of artistic decline, suggesting that their celebrity as establishment figures led them to adopt a style "suitable for the pomposities of gigantic music festivals."[135] Nevertheless, Johnson observes that some of the songs written during Gounod's stay in England in the 1870s are excellent of their kind, such as "Oh happy home" (words by Edward Maitland, 1872), "If thou art sleeping, maiden" (Longfellow, 1872 or 1873) and "The Worker" (Frederic Weatherly, 1873).[138] Gounod's time in Britain also produced arrangements of Scottish folk songs, and settings of poetry by Wordsworth, Charles Kingsley, Thomas Hood, Byron, Shelley and Francis Palgrave.[139]

Legacy

Although only a comparatively small amount of Gounod's music endures in the regular musical repertoire, his influence on later French composers was important. In Cooper's words, "he was more than an individual composer: he was the voice of a deep and permanent strain in the French character ... [A] whole range of emotion, which had been voiceless before, had found in him its ideal expression, and his influence will perhaps never quite disappear for that reason".[92] Cooper suggests that the two sides of Gounod's music nature influenced later French composers as different as Fauré and Massenet, the first drawing on and refining Gounod's classical purity and refinement, and the latter drawing on his romantic and voluptuous side (so much so that he was dubbed "la fille de Gounod").[92] Ravel's comment on Gounod's importance to mélodie is quoted above, and Debussy wrote, "Gounod, for all his weaknesses, is essential … the art of Gounod represents a moment in French sensibility. Whether one wants to or not, that kind of thing is not forgotten".[101]

Music files

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Earlier winners of the Prix de Rome for music included Berlioz (1830) and Ambroise Thomas (1832); among later winners were Georges Bizet (1857), Jules Massenet (1863) and Claude Debussy (1884).[17]

- Ingres discovered Gounod's talent for sketching and said that he would be welcome back to study art at the Institute. Gounod, though pleased, declined to be deflected from his chosen career as a composer.[19]

- Gounod's biographer James Harding (1973) regards Palestrina's influence as key to Gounod's development as a composer; he titles a chapter on the Prix de Rome years "Rome and Palestrina".[26]

- Ah! c'est vous le fou dont ma soeur m'a parlé![30]

- "'Mon ami, ce morceau-là pourrait être signé Cherubini!' Ce sont de véritables décorations, ajoute Gounod, que de semblables paroles venant d'un tel maître, et on les porte avec plus d'orgueil que bien des rubans."[30]

- Bizet later wrote, "Fifteen years ago, when I used to say Sapho and the choruses from Ulysse are masterpieces, people laughed in my face. I was right and I am right today. Only I was destined to be right several years too soon".[44] There were tensions between the two composers in the 1870s, possibly due to a degree of envy on Gounod’s part of Bizet's blossoming talent, but when Bizet died at the age of 37 in 1875 Gounod gave the eulogy at the graveside with tears rolling down his cheeks.[45]

- One review said, "The Reine de Saba looks very much like a failure, owing to the stupidity of the libretto, which does not contain one single interesting scene, and the monotony of the instrumented recitatives. … You could feel the icy mantle of ennui falling gradually upon everybody's shoulders. It is a pity to see a gifted man wasting energy and invention on that which is intractable and worthless".[68]

- Apart from some trimming of episodes not directly relevant to the main love story, the major departure from Shakespeare's plot is that in the climactic tomb scene Juliet wakes up before Romeo dies, and they have time to sing a farewell duet. Other 19th-century composers, including Berlioz, also adopted this device.[71]

- Though destroying his house the Prussians still enjoyed Gounod's music: the Berlin correspondent of The Athenaeum recorded numerous performances of Faust (and other French operas) in the Berlin opera houses in early 1871.[75]

- Some felt that Gounod was too ubiquitous. The Era took exception to a concert in June 1872 "made up of and designed for Gounod, led by Gounod, Palestrina doctored by Gounod, Bach watered by Gounod, Mozart drivelled away by Gounod ... coming it a little bit too strong".[80]

- Weldon sued Gounod for libel, accusing him of being behind defamatory articles about her in the French press. He declined to come to London to defend himself and in his absence Weldon was awarded damages of £10,000.[90] His absolute refusal to pay her this sum made him liable to arrest if he entered Britain.[91]

- In a study of Faust Burton Fisher comments that this milestone seems minor when considered against the 1,250 performances the piece notched up in Paris by 1902, or the fact that the opera was given in every season at Covent Garden in the 47 years from 1863 to 1911.[102]

- In their respective capacities as Director of the Conservatoire, President of the Society of Dramatists and Composers, and Minister of Education, Fine Arts and Religion.[109]

- Cooper adds "Not content with being artists, these eminent Victorians were prone to pose as prophets and, in proportion as their "message" – the actual content of their works – became thinner, the manner in which they stated it became more and more sublime, more portentous and more hollow-sounding".[92]

- Gounod, qui a composé avec verve et imagination une musique colorée et percussive, bien propre à évoquer l'horreur des situations, mais aussi d'un lyrisme fonctionnel mais assez voluptueux dans les arias (dans une partition qu'on peut trouver tout de même parfois académique).[114]

- WorldCat lists recordings of the ballet music conducted by, among many others, Sir Thomas Beecham, Charles Dutoit, Herbert von Karajan, Sir Charles Mackerras, Sir Neville Marriner, Pierre Monteux, Sir Georg Solti and David Zinman.[121]

- In 2007 another critic referred to "the blatant march setting of the Credo and sugar-sweet choral writing" of the Sainte Cécile Mass.[134]

- As "L'île inconnue".[137]

References

- Huebner, Steven. "Gounod, Charles-François", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 21 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Gounod, pp. 2–3

- Harding, pp. 20–22 and 36

- Harding, p. 22

- Harding, p. 23

- Hillemacher, p. 12

- "Charles Gounod", The Musical Times, 1 November 1893, pp. 649–650

- Gounod, pp. 1 and 41

- Harding, pp. 24–25

- Gounod, p. 39

- Gounod, p. 40

- Tiersot, p. 411

- Hillemacher, p. 13; and Harding, pp. 32–33 and 72

- Flynn, p. 2

- Quoted in Tiersot, p. 411

- Hillemacher, p. 14

- "Palmarès de tous les lauréats du Prix de Rome en composition musicale", Musica et Memoria. Retrieved 22 November 2019

- Gounod, pp. 56 and 66–67

- Gounod, p. 68

- Harding, pp. 42–44

- Hendrie, pp. 5–6

- Gounod, quoted in Flynn, p. 2

- Johnson, p. 221

- Cooper, p. 142

- Rushton, p. 206; and Flynn, p. 2

- Harding, p. 31

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 1, p. 84

- Harding, p. 48

- Flynn, p. 3

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 1, p. 93

- Harding, p. 50

- Tiersot, p. 421 and Flynn, p. 3

- Cooper, p. 143

- Cooper, p. 149

- Curtiss, p. 53

- Quoted in Nectoux, p. 27

- Lacombe, p. 210

- Lacombe, p. 249; and Harding, p. 69

- Huebner, pp. 30–31; and Curtiss, p. 60

- Curtiss, p. 59

- "Royal Italian Opera", The Morning Post, 11 August 1851, p. 5

- Holden, p. 144

- Curtiss, p. 61

- Quoted in Curtiss, p. 61

- Kendall-Davies, p 240

- Curtiss, pp. 60–61

- Williams, Anne. "Lewis/Gounod's Bleeding Nonne: An Introduction and Translation of the Scribe/Delavigne Libretto", Romantic Circles. Retrieved 23 November 2019

- Terrier, Agnès (2018). Notes to Naxos DVD 2.110632, "La Nonne sanglante". OCLC 1114338360

- Curtiss, p. 66

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 1, p. 172

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 1, p. 259

- Harding, p. 134

- Durocher, Léon, quoted in "M. Gounod's New Opera", The Musical World, 23 January 1858, pp. 52–53; "Music and Dramatic Gossip", The Athenaeum, 23 January 1858, p. 120; and "Music and the Drama", The Athenaeum, 25 September 1858, p. 403

- Harding, p. 105; and Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 1, p. 259

- Gounod, Charles, Julien Tiersot and Theodore Baker. "Gounod's Letters", The Musical Quarterly, January 1919, pp. 48–49

- "Edmond Audran" Opérette – Théâtre Musical, Académie Nationale de l'Opérette (in French). Retrieved 24 November 2019

- Gounod, p. 156

- "Music and the Drama", The Athenaeum, 26 March 1859, p. 427

- "Foreign Correspondence", The Literary Gazette, 26 March 1859, p. 403

- Gounod, p. 158

- "Vienna", The Musical World, 22 June 1861, pp 395–396; "M. Gounod's Faust at Berlin", The Musical World, 31 January 1863, pp. 69-70; and Kobbé, p. 741

- Huebner, Steven. "Faust (ii)", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 27 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Huebner, Steven. "Philémon et Baucis" Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 24 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Huebner, pp. 58–59

- Huebner, p. 59

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 2, p. 27

- Huebner, Steven. "Reine de Saba, La", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 24 November 2019 (subscription required)

- "Musical and Dramatic Gossip", The Athenaeum, 8 March 1862, p. 338

- Huebner, Steven. "Mireille", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 24 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Flynn, p. 13

- Holden, p. 147

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 2, p. 76

- Kobbé, p. 751

- Huebner, Steven. "Roméo et Juliette", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 24 November 2019 (subscription required)

- "Musical Gossip", The Athenaeum, 11 March 1871, p. 312

- Cooper, p. 146

- "M. Charles François Gounod", The Graphic, 31 August 1872, p. 194

- "About the Royal Choral Society", Royal Choral Society. Retrieved 25 November 2019

- "Philharmonic Society", The Examiner, 11 March 1871, p. 254; and "Gounod Festival", The Orchestra, 2 August 1872, p. 278

- "Our Omnibus", The Era, 2 June 1872, p. 10

- Harding, p. 176

- Davison, pp. 115–116

- Harding, p. 64

- "M. Gounod's Benefit Concert", The Musical World; 14 June 1873, p. 395; "Concerts", The Standard, 18 July 1872, p. 3; "Letter from Paris", The Pall Mall Gazette, 5 December 1872, p. 2; and "St. James's Hall", The Morning Post, 2 June 1873, p. 6

- Harding, p. 166

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 2, p. 127

- Davison, pp. 299–310

- Prod'homme and Dandelot, Vol 2, pp. 151–152

- Harding, p. 209

- "Action by Mrs. Weldon", The Times, 8 May 1885 p. 11

- Foreman and Foreman, p. 263

- Cooper, Martin. Music & Letters, January 1940, pp. 50–59 (subscription required)

- Jones, p. 28; and Nectoux, Jean-Michel. "Fauré, Gabriel (Urbain)", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 28 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Cooper, p. 148

- Deruchie, p. 19

- Harding, p. 192

- Noël and Stoullig, 1878, p. 172

- Harding, p. 199

- Noël and Stoullig, 1882, p. 37

- Noël and Stoullig, 1885, p. 17

- Quoted in Huebner, Steven. "Gounod, Charles-François", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 30 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Fisher, pp. 15–16

- Flynn, p. 225

- Flynn, p. 16

- Flynn, p. 6

- Deruchie, p. 15

- Condé, Gérard (2014). Notes to CPO CD 777863-2 OCLC 8050958590

- Flynn, p. 7

- "Funeral of M. Gounod", The Times, 28 October 1893, p. 5

- Kennedy, Michael. "Gounod, Charles François", The Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford University Press, 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Orledge, Robert. "Gounod, Charles (François)", The Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford University Press, 2011. Retrieved November 2019 (subscription required)

- Steane, John, "Gounod: Sapho", Gramophone, August 1986, pp. 298 and 303

- Huebner, Steven. "Sapho (i)", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 27 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Ducq, Christine."La Nonne sanglante, un sombre divertissement à l'Opéra Comique", La Revue du spectacle, 12 June 2018.

- Cooper, p. 144

- Bury, Laurent. "Miroirs de Gounod: Le Médecin malgré lui", Forum Opera, Le magazine du monde lyrique, 15 November 2017

- Stravinsky, Igor. "The Diaghilev I Knew", The Atlantic Monthly, November 1953

- Cooper, p. 145

- "Faust", Opéra royal de Liege. Retrieved 27 November 2019

- Holden, p. 145

- Faust Ballet Music. WorldCat. Retrieved 1 December 2019

- Clements, Andrew. "Gounod: La Colombe", The Guardian, 25 November 2015

- Steane, John. "Gounod: La Reine de Saba", Gramophone, Awards issue, 2002, pp. 103–104. Retrieved 28 November 2019 (subscription required)

- O'Connor, Patrick. "Gounod: Mireille", Gramophone, December 1992, p. 137. Retrieved 28 November 2019 (subscription required)

- Kobbé, p. 752

- "Music", The Daily News, 15 July 1867, p. 2; and "Gounod and Juliet's Waltz", The Musical World, 2 August 1884, p. 484

- Nichols, Roger (2019). Notes to Chandos CD CHSA5231 OCLC 1090456659

- Fifield, p. 8

- Stepphun, Diether (1983). Notes to Orfeo CD C 1051 831 A OCLC 808038163

- Quoted in Tiersot, p. 424

- Chouquet and Jullien, p. 210

- Tiersot, p. 414

- O'Connor, Patrick. "Gounod: Mors et Vita". Gramophone, February 1993, p. 67. Retrieved 30 November 2019 (subscription required)

- March et al, p. 508

- Johnson, p. 223

- Johnson, p. 222

- Berlioz and Gauthier, VI

- Johnson, Graham (1993). Notes to Hyperion CD CDA66801/2 OCLC 30308095

- Birch, Dinah. "Gounod, Charles François", The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press, 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2019 (subscription required)

Books

- Berlioz, Hector; Théophile Gautier (1904) [1856]. Les nuits d'été. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. OCLC 611290556.

- Chouquet, Gustave; Adolphe Jullien (1916). "Gounod, Charles François". In George Grove; J. A. Fuller Maitland (eds.). A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Second ed.). Philadelphia: Theodore Presser. OCLC 877994749.

- Cooper, Martin (1957). "Charles François Gounod". In A. L. Bacharach (ed.). The Music Masters. Volume 2. London: Penguin. OCLC 851644.

- Davison, Henry (1912). Music During the Victorian Era. London: Reeves. OCLC 1049690727.

- Deruchie, Andrew (2013). The French Symphony at the Fin de siècle. Rochester, NY and Woodbridge, Suffolk: University of Rochester Press, and Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1-58046-382-9.

- Fifield, Christopher (2016). The German Symphony between Beethoven and Brahms. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-03040-9.

- Fisher, Burton (2006). Gounod's Faust. Miami: Opera Journeys. ISBN 978-1-930841-28-4.

- Flynn, Timothy (2016). Charles François Gounod: A Research and Information Guide. New York and London: Routledge Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-138-97019-9.

- Foreman, Lewis; Susan Foreman (2005). London: A Musical Gazetteer. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10402-8.

- Gounod, Charles (1896). W. Hely-Hutchinson (ed.). Autobiographical Reminiscences. London: Heinemann. OCLC 1936009.

- Harding, James (1973). Gounod. London: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-780021-4.

- Hendrie, Gerald (1971). Mendelssohn's Rediscovery of Bach. Bletchley: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0-335-00516-1.

- Hillemacher, Paul (1905). Charles Gounod. Les musiciens célèbres (in French). Paris: Laurens. OCLC 166055265.

- Holden, Amanda (1995) [1993]. The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051385-1.

- Huebner, Steven (1990). The Operas of Charles Gounod. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315329-5.

- Johnson, Graham (2002). A French Song Companion. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924966-4.

- Jones, J. Barrie (1989). Gabriel Fauré: A Life in Letters. London: B T Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5468-0.

- Kendall-Davies, Barbara (2012). The Life and Work of Pauline Viardot Garcia: the Years of Grace, Volume 2, 1863–1910. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-6494-7.

- Kobbé, Gustav (1954) [1919]. The Earl of Harewood (ed.). Kobbé's Complete Opera Book. London and New York: Putnam. OCLC 987953182.

- Lacombe, Hervé (2001). The Keys to French Opera in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 1035918078.

- March, Ivan; Edward Greenfield; Robert Layton; Paul Czajkowski (2008). The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music 2009. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-03336-5.

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1991). Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life. Roger Nichols (trans). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23524-2.

- Noël, Edouard; Edmond Stoullig. Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique (in French). Paris: Charpentier.:

- Prod'homme, Jacques-Gabriel; Alfred Dandelot (1911). Gounod: sa vie et ses oeuvres d'apres des documents inédits (in French). Paris: Delagrave.:

- Rushton, Julian (2001). The Music of Berlioz. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816690-0.

Journals

- Curtiss, Mina (January 1952). "Gounod before Faust". The Musical Quarterly. 38 (1): 48–67. doi:10.1093/mq/XXXVIII.1.48. JSTOR 739593. (subscription required)

- Tiersot, Julien (July 1918). "Charles Gounod: A Centennial Tribute". The Musical Quarterly. 4 (3): 409–439. doi:10.1093/mq/IV.3.409. JSTOR 738223.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Gounod. |

- "Charles Gounod: Works". Retrieved 31 March 2005.

- Works by Charles Gounod at Project Gutenberg

- Free scores by Charles Gounod at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Charles Gounod recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings.

[Category:French ballet composers]]