HMS Bellerophon (1907)

HMS Bellerophon was the lead ship of her class of three dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Navy in the first decade of the 20th century. She spent her whole career assigned to the Home and Grand Fleets. Aside from participating in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 and the inconclusive Action of 19 August, her service during the First World War generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea. The ship was deemed obsolete after the war and was used as a training ship before she was placed in reserve. Bellerophon was sold for scrap in 1921 and broken up beginning the following year.

Bellerophon underway in 1909 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Bellerophon |

| Namesake: | Bellerophon |

| Ordered: | 30 October 1906 |

| Builder: | HM Dockyard, Portsmouth |

| Laid down: | 3 December 1906 |

| Launched: | 27 July 1907 |

| Completed: | February 1909 |

| Commissioned: | 27 February 1909 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap, 8 November 1921 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type: | Bellerophon-class dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 18,596 long tons (18,894 t) (normal) |

| Length: | 526 ft (160.3 m) (o/a) |

| Beam: | 82 ft 6 in (25.1 m) |

| Draught: | 27 ft (8.2 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 5,720 nmi (10,590 km; 6,580 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 680–720 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: | |

Design and description

The design of the Bellerophon class was derived from that of the revolutionary[Note 1] battleship HMS Dreadnought, with a slight increase in size, armour and a more powerful secondary armament.[2] Bellerophon had an overall length of 526 feet (160.3 m), a beam of 82 feet 6 inches (25.1 m), and a normal draught of 27 feet (8.2 m).[3] She displaced 18,596 long tons (18,894 t) at normal load and 22,359 long tons (22,718 t) at deep load. In 1909 her crew numbered 680 officers and ratings and 720 in 1910.[4]

The Bellerophons were powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each driving two shafts, using steam from eighteen Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The turbines were rated at 23,000 shaft horsepower (17,000 kW) and intended to give the ship a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). During Bellerophon's sea trials on 2 November 1908, she reached a top speed of 21.64 knots (40.08 km/h; 24.90 mph) from 26,836 shp (20,012 kW). The ship carried enough coal and fuel oil to give her a range of 5,720 nautical miles (10,590 km; 6,580 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[5]

Armament and armour

The Bellerophon class was equipped with ten breech-loading (BL) 12-inch (305 mm) Mk X guns in five twin-gun turrets, three along the centreline and the remaining two as wing turrets. The centreline turrets were designated 'A', 'X' and 'Y', from front to rear, and the port and starboard wing turrets were 'P' and 'Q' respectively. The secondary, or anti-torpedo boat armament, comprised 16 BL 4-inch (102 mm) Mk VII guns. Two of these guns were each installed on the roofs of the fore and aft centreline turrets and the wing turrets in unshielded mounts, and the other eight were positioned in the superstructure. All secondary guns were in single mounts.[6][Note 2] The ships were also fitted with three 18-inch (450 mm) torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and the third in the stern.[3]

The Bellerophon-class ships had a waterline belt of Krupp cemented armour that was 10 inches (254 mm) thick between the fore and aftmost barbettes. The three armoured decks ranged in thicknesses from 0.75 to 4 inches (19 to 102 mm). The main battery turret faces were 11 inches (279 mm) thick, and the turrets were supported by 9–10 inches (229–254 mm) thick barbettes.[10]

Modifications

An experimental fire-control director was fitted in the forward spotting top and evaluated in May 1910.[11] The guns on the forward turret roof were transferred to the superstructure in 1913–1914 and the roof guns from the wing turrets were remounted in the aft superstructure about a year later; all of the four-inch guns in the superstructure were enclosed to better protect their crews. In addition, a single three-inch (76 mm) anti-aircraft (AA) gun was added on the former searchlight platform between the aft turrets. Shortly afterwards, the guns on the aft turret were removed as were one pair from the superstructure. Around the same time another three-inch AA gun was added to the aft turret roof.[12]

By May 1916, a director had been installed high on the forward tripod mast, but it was not fully wired up by the end of the month when the Battle of Jutland was fought.[13] After the battle approximately 23 long tons (23 t) of additional deck armour was added. Sometime during the year, the ship was fitted to operate kite balloons. By April 1917, Bellerophon had exchanged the three-inch AA gun on 'Y' turret for a four-inch gun and the stern torpedo tube had been removed. In 1918 a high-angle rangefinder was fitted, the starboard aft four-inch gun was removed and the four-inch AA gun was moved to the quarterdeck. After the war ended, both AA guns were removed.[14]

Construction and career

Bellerophon was named after the mythic Greek hero Bellerophon[15] and was the fourth ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy.[16] The ship was ordered on 30 October 1906[17] and was laid down at HM Dockyard, Portsmouth on 3 December 1906. She was launched on 27 July 1907 and completed in February 1909.[7] Including her armament, her cost is variously quoted at £1,763,491[4] or £1,765,342.[8] Bellerophon was commissioned on 20 February 1909, under the command of Captain Hugh Evan-Thomas, and assigned to the Nore Division of the Home Fleet, before it was renamed the 1st Division the following month. She was a participant in combined fleet manoeuvres in June–July and was reviewed by King Edward VII and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia during Cowes Week on 31 July. The ship took part in fleet manoeuvres in April and July[17] and Evan-Thomas was relieved by Captain Trevylyan Napier on 16 August[13] before she began a refit in late 1910 at Portsmouth. Bellerophon participated in the combined exercises for the Mediterranean, Home and Atlantic Fleets in January 1911 and she was lightly damaged in a collision with the battlecruiser Inflexible on 26 May. The ship was present during the Coronation Fleet Review for King George V at Spithead on 24 June and then participated in training exercises with the Atlantic Fleet. She was refitted again later in the year. On 1 May 1912, the 1st Division was renamed the 1st Battle Squadron (BS). The ship was present in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead.[17] Captain Charles Vaughan-Lee relieved Napier on 16 August[13] and then Bellerophon participated in manoeuvres in October. In November, she exercised with the Mediterranean Fleet and visited Athens, Greece.[17] Vaughan-Lee was relieved by Captain Edward Bruen on 18 August 1913[13] and the ship was transferred to the 4th Battle Squadron on 10 March 1914.[17]

First World War

Bellerophon took part in a test mobilisation and fleet review between 17 and 20 July 1914 as part of the British response to the July Crisis. The ship was en route for her scheduled refit at Gibraltar on 26 July when she was recalled to join the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow. She collided with the merchantman SS St Clair off the Orkneys the following day, but suffered little damage. In August, following the outbreak of the First World War, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet,[17] and placed under the command of Admiral John Jellicoe. Most of it was briefly based (22 October to 3 November) at Lough Swilly, Ireland, while the defences at Scapa were strengthened. On the evening of 22 November, the Grand Fleet conducted a fruitless sweep in the southern half of the North Sea; Bellerophon stood with the main body in support of Vice-Admiral David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back in port in Scapa Flow by 27 November.[18][Note 3] On 16 December, the Grand Fleet sortied during the German raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, but failed to make contact with the High Seas Fleet. Bellerophon and the 4th BS conducted target practice north of the Hebrides on 24 December and then rendezvoused with the rest of the Grand Fleet for another sweep of the North Sea on 25–27 December.[19]

Jellicoe's ships, including Bellerophon, conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of Orkney and Shetland.[20] On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers,[21] but they were too far away to participate in the ensuing Battle of Dogger Bank the following day. On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet made a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March. On 11 April, the fleet patrolled the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.[22]

In May, Bellerophon was refitted at Devonport.[17] During 11–14 June, the fleet conducted gunnery practice and battle exercises west of Shetland and more training off Shetland beginning on 11 July. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet was performing numerous training exercises before making another sweep into the North Sea on 13–15 October. Almost three weeks later, Bellerophon participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November.[23]

The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February 1916; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force of cruisers and destroyers to sweep the Heligoland Bight, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea. Another sweep began on 6 March, but had to be abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the escorting destroyers. On the night of 25 March, Bellerophon and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale threatened the light craft, so the fleet was ordered to return to base. On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Imperial Russian Navy relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea. The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft, but only arrived in the area after the Germans had withdrawn. On 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea.[24]

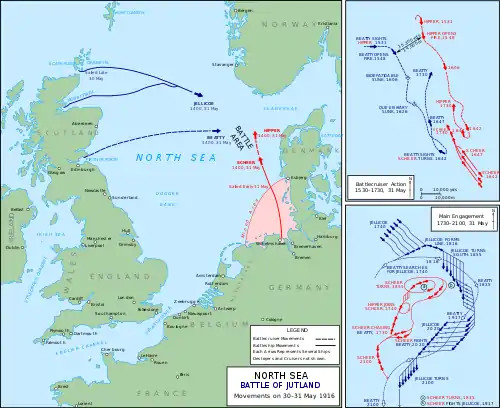

Battle of Jutland

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, and supporting ships, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers. The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[25]

On 31 May, Bellerophon was the fourteenth ship from the head of the battle line after deployment.[17] During the first stage of the general engagement, the ship fired intermittently on the crippled light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden from 18:25,[Note 4] and may have engaged the German dreadnoughts during this time, but did not claim to have hit anything. At 19:17, the ship opened fire at the battlecruiser SMS Derfflinger and scored one hit that glanced off the conning tower. The only significant damage that the armour-piercing, capped (APC) shell caused was from a splinter that destroyed the rangefinder in 'B' turret. About ten minutes later, Bellerophon engaged several German destroyer flotillas with her main armament without result. This was the last time that the ship fired her guns during the battle. She was not damaged and fired a total of 62 twelve-inch shells (42 APC and 21 common pointed, capped) and 14 shells from her four-inch guns during the battle.[26]

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or there was a strong possibility it could be forced into an engagement under suitable conditions.[27] On 31 August Bruen was relieved by Captain Hugh Watson.[13]

During June–September 1917, Bellerophon served as the junior flagship of the 4th BS, flying the flag of Rear-Admiral Roger Keyes and then Rear-Admiral Douglas Nicholson, while the regular flagship, Colossus, was being refitted.[13] The ship was present in Scapa Flow when the battleship Vanguard's magazines exploded on 9 July and her boats rescued two of the three survivors. A large piece of wreckage landed on her deck.[28] Captain Vincent Molteno assumed command on 13 February 1918.[13] Along with the rest of the Grand Fleet, she sortied on the afternoon of 23 April after radio transmissions revealed that the High Seas Fleet was at sea after a failed attempt to intercept the regular British convoy to Norway. The Germans were too far ahead of the British, and no shots were fired.[29] Captain Francis Mitchell relieved Molteno on 12 October.[13] The ship was present at Rosyth, Scotland, when the German fleet surrendered on 21 November and Bellerophon became a gunnery training ship in March 1919 at the Nore as she was thoroughly obsolete in comparison to the latest dreadnoughts.[17] Mitchell was relieved by Captain Humphrey Bowring on 15 March.[13] She was replaced as a training ship by her sister ship, Superb, on 25 September and was reduced to reserve at Devonport where Bellerophon began a refit that lasted until early January 1920. The ship was scheduled for disposal in March 1921 and listed for sale on 14 August. Bellerophon was sold to the Slough Trading Co. on 8 November 1921 for £44,000 and was resold to a German company in September 1922. The ship departed Plymouth, under tow, for Germany on 14 September and was subsequently broken up.[30]

Notes

- Dreadnought was the first battleship with a homogenous main armament, and was the most powerful and fastest battleship in the world at the time of her completion. She made all other battleships obsolete and gave her name to all the subsequent battleships of her type.[1]

- Sources disagree on the type and composition of the secondary armament. Burt claims that they were the older quick-firing QF Mark III guns.[4] Preston and Gardiner & Gray don't identify the type, but do call them quick-firers.[3][7] Parkes also does not identify the type, but he does say that they were 50-calibre guns[8] and Gardiner & Gray agree.[7] Friedman shows the QF Mark III as a 40-calibre gun and states that the 50-calibre BL Mark VII gun armed all of the early dreadnoughts.[9]

- In his 1919 book, Jellicoe generally only named specific ships when they were undertaking individual actions. Usually he referred to the Grand Fleet as a whole, or by squadrons and, unless otherwise specified, this article assumes that Bellerophon is participating in the activities of the Grand Fleet.

- The times used in this section are in UT, which is one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works.

Citations

- Konstam, pp. 4–5

- Burt, p. 75

- Preston, p. 122

- Burt, p. 64

- Burt, pp. 31, 64, 68

- Parkes, pp. 498–99

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 22

- Parkes, p. 498

- Friedman, pp. 97–98

- Burt, pp. 62, 64; Parkes, p. 498

- Brooks, p. 48

- Burt, pp. 66, 68–69

- "H.M.S. Bellerophon (1907)". The Dreadnought Project. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- Burt, pp. 69–70

- Silverstone, p. 217

- Colledge, p. 36

- Burt, p. 71

- Jellicoe, pp. 163–65

- Jellicoe, pp. 179, 182–84

- Jellicoe, p. 190

- Monograph No. 12, p. 224

- Jellicoe, pp. 194–96, 206, 211–12

- Jellicoe, pp. 217–19, 221–22, 228, 243, 246, 250, 253

- Jellicoe, pp. 271, 275, 279–80, 284, 286–90

- Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- Campbell, pp. 156–57, 208, 210, 212, 231–32, 346, 349, 358

- Halpern, pp. 330–32

- Monograph No. 35, p. 175

- Massie, p. 748

- Burt, pp. 71–72

Bibliography

- Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-40788-5.

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

- Konstam, Angus (2013). British Battleships 1914-18 (1): The Early Dreadnoughts. New Vanguard. 200. Botley, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78096-167-5.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank–24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). III. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1921. pp. 209–226. OCLC 220734221.

- Monograph No. 35: Home Waters-Part IX 1st May, 1917, to 31st July, 1917 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). XIX. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1939. OCLC 220734221.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. V (reprint of the 1931 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-255-1.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916 (repr. ed.). London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Bellerophon (1907). |