HM Prison Dartmoor

HM Prison Dartmoor is a Category C men's prison, located in Princetown, high on Dartmoor in the English county of Devon. Its high granite walls dominate this area of the moor. The prison is owned by the Duchy of Cornwall, and is operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service.

| |

| |

| Location | Princetown, Devon |

|---|---|

| Security class | Adult Male/Category C |

| Population | 640 (as of January 2016) |

| Opened | 1809 |

| Managed by | HM Prison Services |

| Governor | Bridie Oakes-Richards |

| Website | Dartmoor at justice.gov.uk |

History

In 1805, the United Kingdom was at war with Napoleonic France, a conflict during which thousands of prisoners were taken and confined in prison "hulks" or derelict ships. This was considered unsafe, partially due to the proximity of the Royal Naval dockyard at Devonport (then called Plymouth Dock), and as living conditions were appalling in the extreme, a prisoner of war depot was planned in the remote isolation of Dartmoor. Construction started in 1806, taking three years to complete. In 1809, the first French prisoners arrived and were joined by American POWs taken in the War of 1812. At one time, the prison population numbered almost 6,000. By July 1815 at least 270 Americans and 1,200 French prisoners had died. [2] Both French and North American wars were concluded in 1815, and repatriations began. The prison then lay empty until 1850, when it was largely rebuilt and commissioned as a convict gaol. After originally being buried on the moor, due to the establishment of the prison farm in about 1852, all the prisoners' remains were exhumed and re-interred in two cemeteries behind the prison.

Early history

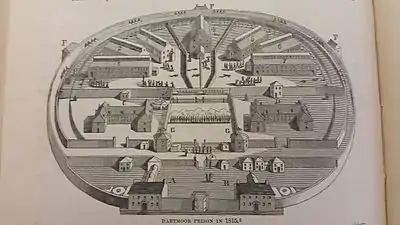

Designed by Daniel Asher Alexander and constructed originally between 1806 and 1809 by local labour, to hold prisoners of the Napoleonic Wars, it was also used to hold American prisoners from the War of 1812. Although the war ended with the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814, many American prisoners of war still remained in Dartmoor.

From the spring of 1813 until March 1815, about 6,500 American sailors were imprisoned at Dartmoor. These were either naval prisoners or impressed American seamen discharged from British vessels. Whilst the British were in overall charge of the prison, the prisoners created their own governance and culture. They had courts which meted out punishments, a market, a theatre and a gambling room. About 1,000 of the prisoners were Black.[3][4]

After the prisoners heard of the Treaty of Ghent, signed on 24 December 1814, they expected immediate release, but the British government refused to let them go on parole or take any steps until the treaty was ratified by the United States Senate, 17 February 1815. It took several weeks for the American agent to secure ships for their transportation home, and the men grew very impatient. On 4 April, a food contractor attempted to work off some damaged hardtack on them in place of soft bread and was forced to yield by their insurrection. The commandant, Captain T. G. Shortland, suspected them of a design to break out of the gaol. This was the reverse of the truth in general, as they would lose their chance of going on the ships, but a few had made threats of the sort, and the commandant was very uneasy.[4]

At about 6:00 pm on 6 April, Shortland discovered a hole from one of the five prisons to the barrack yard near the gun racks. Some prisoners were outside the fence, noisily pelting each other with turf, and many more were near the breach (and the gambling tables), though the signal for return to prisons had sounded. Shortland was convinced of a plot and rang the alarm bell to collect the officers and have the guards ready. This precaution brought back a crowd just going to quarters. Just then a prisoner broke a gate chain with an iron bar and a number of the prisoners pressed through to the prison market square. After attempts at persuasion, Shortland ordered a charge which drove some of the prisoners in. Those near the gate, however, hooted at and taunted the soldiery, who fired a volley over their heads. The crowd yelled louder and threw stones, and the soldiers, probably without orders, fired a direct volley which killed and wounded a large number. Then they continued firing at the prisoners, many of whom were now struggling to get back inside the blocks.[4]

Finally the captain, a lieutenant and the hospital surgeon (the other officers being at dinner) succeeded in stopping the shooting and caring for the wounded – about 60, 30 seriously, besides seven killed outright. The affair was examined by a joint commission, Charles King for the United States and F. S. Larpent for Great Britain, which exonerated Shortland, justified the initial shooting and blamed the subsequent deaths on unknown culprits. The British government provided for the families of the killed, pensioned the disabled and promoted Shortland.[4]

A memorial has been erected to the 271 POWs (mostly seamen) who are buried in the prison grounds.

Dartmoor was re-opened in 1851 as a civilian prison, but closed again in 1917, when it was converted into a Home Office Work Centre for certain conscientious objectors granted release from prison; cells were kept unlocked, inmates wore their own clothes and could visit the village in their off-duty time. It was re-opened as a prison in 1920 and has contained some of Britain's most serious offenders.

Dartmoor mutiny

On 24 January 1932, there was a major disturbance at the prison. The cause of the riots is generally attributed to prisoners' perceptions of poor quality of the food, not generally but on specific days prior to the disturbance when it was suspected it had been tampered with.[5] There had also been other instances of disobedience prior to this, according to the official du Parcq report into the incident, such as a model prisoner attacking a popular guard with a razor blade and rough treatment by prisoners of a prisoner being removed to solitary.[6] At the parade later that day, 50 prisoners refused orders, and the rest were marched back to their cells but refused to enter. At this point, the prison governor and his staff fled to an unused part of the prison and secured themselves there. The prisoners then released those held in solitary. There was extensive damage to property, and a prisoner was shot by one of the staff, but no prison staff were injured.[7] According to Fitzgerald (1977), "Reinforcements arrived, and within fifteen minutes these 'vicious brutes', who for some two hours had terrorized well-armed prison staff, and effectively controlled the prison, had surrendered and been locked up again".[8]

Post-2000 history

Dartmoor Prison received a Grade II heritage listing in 1987.[9]

In 2001, a Board of Visitors report condemned sanitation, as well as highlighting a list of urgent repairs needed.[10] A year later, the prison was converted to a Category C prison for less violent offenders.

In 2002, the Prison Reform Trust warned that the prison may be breaching the Human Rights Act 1998 due to severe overcrowding at the jail.[11] A year later, however, the Chief Inspector of Prisons declared that the prison had made substantial improvements to its management and regime.[12]

In March 2008, staff at the prison passed a vote of no confidence in the governor Serena Watts, claiming they felt bullied by managers and unsafe.[13]

The previous governor, Tony Corcoran, took up the post of governor of HMP Haverigg in early 2013.

The prison today

.jpg.webp)

Dartmoor still has a misplaced reputation as being a high-security prison that is escape-proof. Now a Category C prison, Dartmoor houses mainly non-violent offenders and white-collar criminals. It also holds sex offenders and offers sex offender treatment programmes intended to make the offender realise their behaviour is unacceptable.[14] Some subsequently volunteer for behaviour-changing treatment with medication under a scheme being piloted at HMP Whatton, which has had encouraging results.[14]

Dartmoor offers cell accommodation on six wings. Education is available at the prison (full and part-time), and ranges from basic educational skills to Open University courses. Vocational training includes electronics, brickwork and carpentry courses up to City & Guilds and NVQ level, Painting and Decorating courses, industrial cleaning and desktop publishing. Full-time employment is also available in catering, farming, gardening, laundry, textiles, Braille, contract services, furniture manufacturing and polishing. Employment is supported with NVQ or City & Guilds vocational qualifications. All courses and qualifications at Dartmoor are operated by South Gloucestershire and Stroud College and Cornwall College.

The "Dartmoor Jailbreak" is a yearly event, in which members of the public "escape" from the prison and must travel as far as possible in four days, without directly paying for transport. By doing so they raise money for charity.[15]

Future

In September 2013, it was announced that discussions would commence with the Duchy of Cornwall about the long-term future of HMP Dartmoor.[16] In January 2014 it was stated on the BBC news website that the notice period with the Duchy for closing is 10 years.[17] In November 2015 the Ministry of Justice confirmed that, as part of a major programme to replace older prisons, it would not renew its lease on the prison.[18]

It was announced on 25 October 2019 that HMP Dartmoor will close in 2023.[19]

Dartmoor Prison Museum

The Dartmoor Prison Museum, located in the old dairy buildings, focuses on the history of HMP Dartmoor. Exhibits include the prison's role in housing prisoners of war from the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, manacles and weapons, memorabilia, clothing and uniforms, famous prisoners, and the changed focus of the prison. It also sells (2015) garden ornaments and other items made in the prison concrete and carpentry shops by prisoners engaged in educational courses.

There are also displays and information on less well known aspects of the prison such as the incarceration of conscientious objectors during world war one.

Notable former inmates

- Michael Davitt

- Peter Hammond, founder of Hammond, Louisiana, USA

- Fred Longden

- John Rodker

- Moondyne Joe

- Thomas William Jones, Baron Maelor

- John Boyle O'Reilly

- Arthur Owens

- Éamon de Valera

- F. Digby Hardy

- John Williams

- Frank Mitchell

- Reginald Horace Blyth

- Darkie Hutton

- John George Haigh

- Bruno Tolentino, who eventually was deported to Brazil where the major part of his oeuvre was published. "A Balada do Cárcere" (1996) is a poetic recollection of the time spent in Dartmoor.[20]

- Fahad Mihyi, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine terrorist behind the 1978 London bus attack[21]

In popular culture

- In the 1963 James Bond movie From Russia with Love, the main villainous henchman, SPECTRE assassin Red Grant (played by Robert Shaw) is described as a psychopathic paranoid and a convicted murderer, who once escaped from Dartmoor Prison.

- The adventure story A Rogue by Compulsion. An Affair of the Secret Service (1915) by Victor Bridges begins with a dramatic escape from Dartmoor.[22]

- In Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), Mr. Christian states to Captain Bligh that Seaman Burkitt chose service in the Royal Navy as an alternative to imprisonment at Dartmoor.

- In the John Galsworthy play, Escape, Dartmoor is the prison whence the hero, Captain Denman escapes. The stage production in 1927 starred Leslie Howard and the 1930 film version starred Sir Gerald du Maurier.

- The 1929 movie A Cottage on Dartmoor begins with an escapee from Dartmoor prison, and proceeds to a flashback as to how he came to be incarcerated.

- An escaped convict from Dartmoor figures in Nevil Shute's first novel Marazan, published in 1926.

- Decline and Fall, a novel by Evelyn Waugh, first published in 1928 makes thinly disguised references to Dartmoor Prison.

- Dartmoor Prison is mentioned in The Thirteen Problems, a short story collection written by Agatha Christie, and first published in 1932. Christie's The Sittaford Mystery (1931) is set on Dartmoor and features an escaped prisoner.

- Arthur Conan Doyle made reference to 'Princetown Prison' in four stories that he wrote between 1890 and 1903. In The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902), an escaped prisoner from Princetown serves as a red herring for Holmes and Watson.

- Dressed to Kill, a 1946 Sherlock Holmes film uses Dartmoor Prison in the plot as the supposed location where three music boxes were made that contain a secret code for a criminal gang.[23]

- Referenced in Bob Miller's song, Twenty-One Years.

- In the Tales of Old Dartmoor episode (recorded in 1956) of The Goons radio comedy series, Grytpype-Thynne arranges for the prison to put to sea to visit the Château d'If in France as part of a plan to find the treasure of the Count of Monte Cristo hid there. A cardboard replica is left in its place, which is left standing after the original Dartmoor Prison sinks with all hands at the end of the episode.

- In an episode of The Saint television series entitled "Escape Route" (1966), Simon Templar (Roger Moore) is sent to Dartmoor to uncover a planned escape.

- Comedy band The Barron Knights' 1978 UK No. 3 hit single "A Taste of Aggro", a medley of parodies, included a version of "The Smurf Song" featuring, in place of the Smurfs, a group of bank robbers from Catford who have escaped from Dartmoor Prison.[24]

- In 1988, the prison played host to a storyline in EastEnders, where Den Watts (played by Leslie Grantham) was being held on remand for arson. He was also joined for some of the storyline by Nick Cotton (played by John Altman), who was imprisoned for a different offence. The prison was called Dickens Hill.

- Dartmoor is frequently mentioned in the Agent Z series of comical children's books written by Mark Haddon.

- Dartmoor prison is implicated in the local Dartmoor 'Hairy hands' ghost story/legend.

- Dartmoor prison plays a central role in The Lively Lady, American author Kenneth Roberts' 1931 historical novel taking place during The War of 1812

- In the first episode of the second series of James May's Man Lab, James May and Oz Clarke were demonstrating map-reading skills by pretending to escape from Dartmoor prison and cross Dartmoor to their escape car[25] (although they had to start their escape from outside the prison grounds as they were not allowed permission inside the prison).

- One of the intersecting story lines in Edward Marston's novel, Shadow of the Hangman (2013) involves two American seamen who escape during the 1815 riot.

- The prison and the American sailors imprisoned towards the end of the War of 1812 are central to Simon Mayo's 2018 novel Mad Blood Stirring.

- In The Voice of Terror (1942), Sherlock Holmes is angrily confronted in a tavern by an ex-convict who says he’d been sent to Dartmoor Prison by Holmes.

References

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 1068.

- Adkins, Roy; Adkins, Lesley (2007). The War for All Oceans. London: Abacus. p. 460. ISBN 978-0-349-11916-8.

- 1812: War with America, Jon Latimer, Harvard University Press, 2007 p. 239

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Fitzgerald, M. (1977) Prisoners in Revolt, Harmondsworth: Penguin pg.123

- Fitzgerald, M. (1977) Prisoners In Revolt, Harmondsworth: Penguin pg.124

- Fitzgerald, M. (1977) Prisoners In Revolt, Harmondsworth: Penguin pg.124-5

- Fitzgerald, M. (1977) Prisoners In Revolt, Harmondsworth: Penguin pg.126

- "Hm Dartmoor Prison, Dartmoor Forest". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Dartmoor prison sanitation 'unacceptable'". BBC News. 14 November 2001.

- "Dartmoor breaches Human Rights". BBC News. 19 September 2002.

- "Prison praised for progress". BBC News. 15 July 2003.

- "Dartmoor prison staff 'bullied'". BBC News. 19 March 2008.

- Decca Aitkenhead (18 January 2013). "Chemical castration: the soft option?". Guardian Newspapers. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- . Dartmoor Prison Break. Retrieved 3rd March 2020

- "Dartmoor Prison set to close in latest jail shake-up".

- "Drug use and cell sharing 'still issues at Dartmoor Prison'".

- "Spending review: Nine new prisons to replace 'Victorian' jails". BBC News. 9 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/breaking-dartmoor-prison-close-2023-20721071

- "Bruno Tolentino". Vide Editorial. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Naomi Pfefferman (9 May 2003). "'Terrorist' Helped Israeli Heal". Jewish Journal. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- Bridges, Victor (1915). "A Rogue by Compulsion. An Affair of the Secret Service". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- Weaver, Tom (2007). Universal horrors: the studio's classic films, 1931–1946. McFarland.

- Barron Knights Lyrics: A Taste Of Aggro Lyrics. Lyrics on Demand. Retrieved 15 January 2014

- "BBC Two – James May's Man Lab, Series 2, Episode 1". BBC. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dartmoor Prison. |