Haggadah

The Haggadah (Hebrew: הַגָּדָה, "telling"; plural: Haggadot) is a Jewish text that sets forth the order of the Passover Seder. Reading the Haggadah at the Seder table is a fulfillment of the mitzvah to each Jew to "tell your son" of a story from the Book of Exodus about Israelites being delivered from slavery, involving an Exodus from Egypt through the hand of Yahweh in the Torah ("And thou shalt tell thy son in that day, saying: It is because of that which the LORD did for me when I came forth out of Egypt." Ex. 13:8).

Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews also apply the term Haggadah to the service itself, as it constitutes the act of "telling your son."

Passover Seder according to the Haggadah

Kadeish (blessings and the first cup of wine)

Kadeish is the Hebrew imperative form of Kiddush.[1] This Kiddush is a blessing similar to that which is recited on all of the pilgrimage festivals, but also refers to matzot and the exodus from Egypt. Acting in a way that shows freedom and majesty, many Jews have the custom of filling each other's cups at the Seder table. The Kiddush is traditionally said by the father of the house, but all Seder participants participate by reciting the Kiddush and drinking at least a majority of a cup of wine.

Ur'chatz (wash hands)

Partakers wash their hands in preparation for eating wet fruit and vegetables, which happens in the next stage. Technically, according to Jewish law, whenever one partakes of fruit or vegetables dipped in liquid, one must wash one's hands, if the fruit or vegetable remains wet.[2] However, this situation does not often arise at other times of the year because either one will dry fruits and vegetables before eating them, or one has already washed one's hands, because one must also wash one's hands before eating bread.

According to most traditions, no blessing is recited at this point in the Seder, unlike the blessing recited over the washing of the hands before eating bread. However, followers of Rambam or the Gaon of Vilna do recite a blessing.

Karpas

Each participant dips a sprig of parsley or similar leafy green into either salt water (Ashkenazi custom said to serve as a reminder of the tears shed by their enslaved ancestors), vinegar (Sephardi custom) or charoset (older Sephardi custom; still common among Yemenite Jews).[3]

Yachatz (breaking of the middle matzah)

Three matzot are stacked on the seder table; at this stage, the middle matzah of the three is broken in half.[4] The larger piece is hidden, to be used later as the afikoman, the "dessert" after the meal. The smaller piece is returned to its place between the other two matzot.

Magid (relating the Exodus)

The story of Passover, and the change from slavery to freedom is told.[5] At this point in the Seder, Sefardic Jews (North African) have a custom of raising the Seder plate over the heads of all those present while chanting: Moroccan Jews sing "Bivhilu yatzanu mimitzrayim, halahma anya b'nei horin" (In haste we went out of Egypt [with our] bread of affliction, [now we are] free people), Algerian Jews sing "Ethmol 'ayinu abadim, hayom benei 'horin, hayom kan, leshana habaa bear'a deYisrael bene 'horin" (Yesterday we were slaves, today we are free, today we are here -in exile-, next year we will be in Israel free".

Ha Lachma Anya (invitation to the Seder)

The matzot are uncovered, and referred to as the "bread of affliction". Participants declare in Aramaic an invitation to all who are hungry or needy to join in the Seder. Halakha requires that this invitation be repeated in the native language of the country.

Ma Nishtanah (The Four Questions)

The Mishnah details questions one is obligated to ask on the night of the Seder. It is customary for the youngest child present to recite the four questions.[6] Some customs hold that the other participants recite them quietly to themselves as well. In some families, this means that the requirement remains on an adult "child" until a grandchild of the family receives sufficient Jewish education to take on the responsibility. If a person has no children capable of asking, the responsibility falls to the spouse, or another participant.[7] The need to ask is so great that even if a person is alone at the seder he is obligated to ask himself and to answer his own questions.[7]

Why is this night different from all other nights?

- Why is it that on all other nights during the year we eat either leavened bread or matza, but on this night we eat only matza?

- Why is it that on all other nights we eat all kinds of vegetables, but on this night we eat bitter herbs?

- Why is it that on all other nights we do not dip [our food] even once, but on this night we dip them twice?

- Why is it that on all other nights we dine either sitting upright or reclining, but on this night we all recline?

The Four Sons

The traditional Haggadah speaks of "four sons—one who is wise, one who is wicked, one who is simple, and one who does not know to ask".[8] The number four derives from the four passages in the Torah where one is commanded to explain the Exodus to one's son.[9] Each of these sons phrases his question about the seder in a different way. The Haggadah recommends answering each son according to his question, using one of the three verses in the Torah that refer to this exchange.

The wise son asks "What are the statutes, the testimonies, and the laws that God has commanded you to do?" One explanation for why this very detailed-oriented question is categorized as wise, is that the wise son is trying to learn how to carry out the seder, rather than asking for someone else's understanding of its meaning. He is answered fully: You should reply to him with [all] the laws of pesach: one may not eat any dessert after the paschal sacrifice.

The wicked son, who asks, "What is this service to you?", is characterized by the Haggadah as isolating himself from the Jewish people, standing by objectively and watching their behavior rather than participating. Therefore, he is rebuked by the explanation that "It is because God acted for my sake when I left Egypt." (This implies that the Seder is not for the wicked son because the wicked son would not have deserved to be freed from Egyptian slavery.) Where the four sons are illustrated in the Haggadah, this son has frequently been depicted as carrying weapons or wearing stylish contemporary fashions.

The simple son, who asks, "What is this?" is answered with "With a strong hand the Almighty led us out from Egypt, from the house of bondage."

And the one who does not know to ask is told, "It is because of what the Almighty did for me when I left Egypt."

Some modern Haggadahs mention "children" instead of "sons", and some have added a fifth child. The fifth child can represent the children of the Shoah who did not survive to ask a question[10] or represent Jews who have drifted so far from Jewish life that they do not participate in a Seder.[11]

For the former, tradition is to say that for that child we ask "Why?" and, like the simple child, we have no answer.

"Go and learn"

Four verses in Deuteronomy (26:5–8) are then expounded, with an elaborate, traditional commentary. ("5. And thou shalt speak and say before the LORD thy God: 'A wandering Aramean was my parent, and they went down into Egypt, and sojourned there, few in number; and became there a nation, great, mighty, and populous. 6. And the Egyptians dealt ill with us, and afflicted us, and laid upon us hard bondage. 7. And we cried unto the LORD, the God of our parents, and the LORD heard our voice, and saw our affliction, and our toil, and our oppression. 8 And the LORD brought us forth out of Egypt with a strong hand and an outstretched arm, and with great terribleness, and with signs, and with wonders.")

The Haggadah explores the meaning of those verses, and embellishes the story. This telling describes the slavery of the Jewish people and their miraculous salvation by God. This culminates in an enumeration of the Ten Plagues:

- Dam (blood) – All the water was changed to blood

- Tzefardeyah (frogs) – An infestation of frogs sprang up in Egypt

- Kinim (lice) – The Egyptians were afflicted by lice

- Arov (wild animals) – An infestation of wild animals (some say flies) sprang up in Egypt

- Dever (pestilence) – A plague killed off the Egyptian livestock

- Sh'chin (boils) – An epidemic of boils afflicted the Egyptians

- Barad (hail) – Hail rained from the sky

- Arbeh (locusts) – Locusts swarmed over Egypt

- Choshech (darkness) – Egypt was covered in darkness

- Makkat Bechorot (killing of the first-born) – All the first-born sons of the Egyptians were slain by God

With the recital of the Ten Plagues, each participant removes a drop of wine from his or her cup using a fingertip. Although this night is one of salvation, the sages explain that one cannot be completely joyous when some of God's creatures had to suffer. A mnemonic acronym for the plagues is also introduced: "D'tzach Adash B'achav", while similarly spilling a drop of wine for each word.

At this part in the Seder, songs of praise are sung, including the song Dayenu, which proclaims that had God performed any single one of the many deeds performed for the Jewish people, it would have been enough to obligate us to give thanks. After this is a declaration (mandated by Rabban Gamliel) of the reasons of the commandments concerning the Paschal lamb, Matzah, and Maror, with scriptural sources. Then follows a short prayer, and the recital of the first two psalms of Hallel (which will be concluded after the meal). A long blessing is recited, and the second cup of wine is drunk.

Rohtzah (ritual washing of hands)

The ritual hand-washing is repeated, this time with all customs including a blessing.[12]

Motzi Matzah (blessings over the Matzah)

Two blessings are recited.[13] First one recites the standard blessing before eating bread, which includes the words "who brings forth" (motzi in Hebrew).[14] Then one recites the blessing regarding the commandment to eat Matzah. An olive-size piece (some say two) is then eaten while reclining.

Maror (bitter herbs)

The blessing for the eating of the maror (bitter herbs) is recited and then it is dipped into the charoset and eaten.[14][15]

Koreich (sandwich)

The maror (bitter herb) is placed between two small pieces of matzo, similarly to how the contents of a sandwich are placed between two slices of bread, and eaten.[16] This follows the tradition of Hillel, who did the same at his Seder table 2,000 years ago (except that in Hillel's day the Paschal sacrifice, matzo, and maror were eaten together.)

Shulchan Orech (the meal)

The festive meal is eaten.[17] Traditionally it begins with the charred egg on the Seder plate.[18]

Tzafun (eating of the afikoman)

The afikoman, which was hidden earlier in the Seder, is traditionally the last morsel of food eaten by participants in the Seder.[19]

Each participant receives an at least olive-sized portion of matzo to be eaten as afikoman. After the consumption of the afikoman, traditionally, no other food may be eaten for the rest of the night. Additionally, no intoxicating beverages may be consumed, with the exception of the remaining two cups of wine.

Bareich (Grace after Meals)

The recital of Birkat Hamazon.[20]

Kos Shlishi (the Third Cup of Wine)

The drinking of the Third Cup of Wine.

Note: The Third Cup is customarily poured before the Grace after Meals is recited because the Third Cup also serves as a Cup of Blessing associated with the Grace after Meals on special occasions.

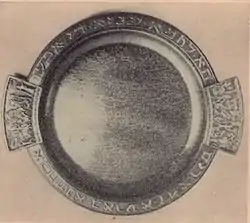

Kos shel Eliyahu ha-Navi (cup of Elijah the Prophet)

In many traditions, the front door of the house is opened at this point. Psalms 79:6–7 is recited in both Ashkenazi and Sephardi traditions, plus Lamentations 3:66 among Ashkenazim.

Most Ashkenazim have the custom to fill a fifth cup at this point. This relates to a Talmudic discussion that concerns the number of cups that are supposed to be drunk. Given that the four cups are in reference to the four expressions of redemption in Exodus 6:6–7, some rabbis felt that it was important to include a fifth cup for the fifth expression of redemption in Exodus 6:8. All agreed that five cups should be poured but the question as to whether or not the fifth should be drunk, given that the fifth expression of redemption concerned being brought into the Land of Israel, which—by this stage—was no longer possessed of an autonomous Jewish community, remained insoluble. The rabbis determined that the matter should be left until Elijah comes (in reference to the notion that Elijah's arrival would precipitate the coming of the Messiah, at which time all halakhic questions will be resolved) and the fifth cup came to be known as the Kos shel Eliyahu ("Cup of Elijah"). Over time, people came to relate this cup to the notion that Elijah will visit each home on Seder night as a foreshadowing of his future arrival at the end of the days, when he will come to announce the coming of the Jewish Messiah.

In the late 1980s, Jewish feminists introduced the idea of placing a "Cup of Miriam" filled with water (to represent the well that existed as long as Miriam, Moses' sister, was alive in the desert) beside the Cup of Elijah. Many liberal Jews now include this ritual at their seders as a symbol of inclusion.[21]

Hallel (songs of praise)

The entire order of Hallel which is usually recited in the synagogue on Jewish holidays is also recited at the Seder table, albeit sitting down.[22] The first two psalms, 113 and 114, are recited before the meal. The remaining psalms 115–118, are recited at this point (in the Hallel section, after Bareich). Psalm 136 (the Great Hallel) is then recited, followed by Nishmat, a portion of the morning service for Shabbat and festivals.

There are a number of opinions concerning the paragraph Yehalelukha which normally follows Hallel, and Yishtabakh, which normally follows Nishmat. Most Ashkenazim recite Yehalelukha immediately following the Hallel proper, i.e. at the end of Psalm 118, except for the concluding words. After Nishmat, they recite Yishtabakh in its entirety. Sephardim recite Yehalelukha alone after Nishmat.

Afterwards the Fourth Cup of Wine is drunk and a brief Grace for the "fruit of the vine" is said.

Nirtzah

The Seder concludes with a prayer that the night's service be accepted.[23] A hope for the Messiah is expressed: "L'Shana Haba'ah b'Yerushalayim! – Next year in Jerusalem!" Jews in Israel, and especially those in Jerusalem, recite instead "L'shanah haba'ah b'Yerushalayim hab'nuyah! – Next year in the rebuilt Jerusalem!"

Although the 15 orders of the Seder have been completed, the Haggadah concludes with additional songs which further recount the miracles that occurred on this night in Ancient Egypt as well as throughout history. Some songs express a prayer that the Beit Hamikdash will soon be rebuilt. The last song to be sung is Chad Gadya ("One Kid [young goat]"). This seemingly childish song about different animals and people who attempted to punish others for their crimes and were in turn punished themselves, was interpreted by the Vilna Gaon as an allegory of the retribution God will levy over the enemies of the Jewish people at the end of days.

Following the Seder, those who are still awake may recite the Song of Songs, engage in Torah learning, or continue talking about the events of the Exodus until sleep overtakes them.

History

Authorship

According to Jewish tradition, the Haggadah was compiled during the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods, although the exact date is unknown. It could not have been written earlier than the time of Judah bar Ilai (circa 170 CE), who is the latest tanna to be quoted therein. Rav and Shmuel (circa 230 CE) argued on the compilation of the Haggadah,[24] and hence it had not been completed as of then. Based on a Talmudic statement, it was completed by the time of "Rav Nachman".[25] There is a dispute, however, to which Rav Nachman the Talmud was referring: According to some commentators, this was Rav Nachman bar Yaakov[26] (circa 280 CE), while others maintain this was Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak[27] (360 CE).

However, the Malbim,[28] along with a minority of commentators, believe that Rav and Shmuel were not arguing on its compilation, but rather on its interpretation, and hence it was completed before then. According to this explanation, the Haggadah was written during the lifetime of Judah ha-Nasi (who was a student of Judah bar Ilia and the teacher of Rav and Shmuel) the compiler of the Mishnah. The Malbim theorized that the Haggadah was written by Judah ha-Nasi himself.

One of the most ancient parts is the recital of the "Hallel," which, according to the Mishnah (Pesachim 5:7), was sung at the sacrifice in the Temple in Jerusalem, and of which, according to the school of Shammai, only the first chapter shall be recited. After the Psalms a blessing for the Redemption is to be said. This blessing, according to R. Tarfon, runs as follows: "Praised art Thou, O Lord, King of the Universe, who hast redeemed us, and hast redeemed our fathers from Egypt."

Another part of the oldest ritual, as is recorded in the Mishnah, is the conclusion of the "Hallel" (up to Psalms 118), and the closing benediction of the hymn "Birkat ha-Shir," which latter the Amoraim explain differently,[29] but which evidently was similar to the benediction thanking God, "who loves the songs of praise," used in the present ritual.

These blessings, and the narrations of Israel's history in Egypt, based on Deuteronomy 26:5–9 and on Joshua 24:2–4, with some introductory remarks, were added in the time of the early Amoraim, in the third century CE.

In post-Talmudic times, during the era of the Geonim, selections from midrashim were added; most likely Rabbi Amram Gaon (c. 850) was the originator of the present collection, as he was the redactor of the daily liturgy in the siddur. Of these midrashim one of the most important is that of the four children, representing four different attitudes towards why Jews should observe Passover. This division is taken from the Jerusalem Talmud[30] and from a parallel passage in the Mekhilta; it is slightly altered in the present ritual. Other rabbinic quotes from the aggadah literature are added, as the story of R. Eliezer, who discussed the Exodus all night with four other rabbis, which tale is found in an altogether different form in the Tosefta.

While the main portions of the text of the Haggadah have remained mostly the same since their original compilation, there have been some additions after the last part of the text. Some of these additions, such as the cumulative songs "One little goat" ("חד גדיא") and "Who Knows One?" ("אחד מי יודע"), which were added sometime in the fifteenth century, gained such acceptance that they became a standard to print at the back of the Haggadah.

The text of the Haggadah was never fixed in one, final form, as no rabbinic body existed which had authority over such matters. Instead, each local community developed its own text. A variety of traditional texts took on a standardized form by the end of the medieval era on the Ashkenazi (Eastern European), Sephardic (Spanish-Portuguese) and Mizrahi (Jews of North Africa and the Middle east) community.

The Karaites[31][32] and also the Samaritans developed their own Haggadot which they use to the present day.[33]

During the era of the Enlightenment the European Jewish community developed into groups which reacted in different ways to modifications of the Haggadah.

- Orthodox Judaism accepted certain fixed texts as authoritative and normative, and prohibited any changes to the text.

- Modern Orthodox Judaism and Conservative Judaism allowed for minor additions and deletions to the text, in accord with the same historical-legal parameters as occurred in previous generations. Rabbis within the Conservative Judaism, studying the liturgical history of the Haggadah and Siddur, conclude that there is a traditional dynamic of innovation, within a framework conserving the tradition. While innovations became less common in the last few centuries due to the introduction of the printing press and various social factors, Conservative Jews take pride in their community's resumption of the traditional of liturgical creativity within a halakhic framework.

- Reform Judaism holds that there are no normative texts, and allowed individuals to create their own haggadahs. Reform Jews take pride in their community's resumption of liturgical creativity outside a halakhic framework; although the significant differences they introduced make their texts incompatible with Jews who wish to follow a seder according to Jewish tradition.

Manuscript history

The oldest surviving complete manuscript of the Haggadah dates to the 10th century. It is part of a prayer book compiled by Saadia Gaon. It is now believed that the Haggadah first became produced as an independent book in codex form around 1000 CE.[34] Maimonides (1135–1204) included the Haggadah in his code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah. Existing manuscripts do not go back beyond the thirteenth century. When such a volume was compiled, it became customary to add poetical pieces.

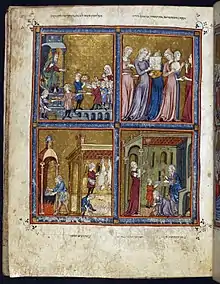

The earliest surviving Haggadot produced as works in their own right are manuscripts from the 13th and 14th centuries, such as the Golden Haggadah (probably Barcelona c. 1320, now British Library) and the Sarajevo Haggadah (late fourteenth century). It is believed that the first printed Haggadot were produced in 1482, in Guadalajara, Spain; however, this is mostly conjecture, as there is no printer's colophon. The oldest confirmed printed Haggadah was printed in Soncino, Lombardy in 1486 by the Soncino family.

Although the Jewish printing community was quick to adopt the printing press as a means of producing texts, the general adoption rate of printed Haggadot was slow. By the end of the sixteenth century, only twenty-five editions had been printed. This number increased to thirty-seven during the seventeenth century, and 234 during the eighteenth century. It is not until the nineteenth century, when 1,269 separate editions were produced, that a significant shift is seen toward printed Haggadot as opposed to manuscripts. From 1900–1960 alone, over 1,100 Haggadot were printed.[35] It is not uncommon, particularly in America, for haggadot to be produced by corporate entities, such as coffee maker Maxwell House – see Maxwell House Haggadah – serving as texts for the celebration of Passover, but also as marketing tools and ways of showing that certain foods are kosher.[36]

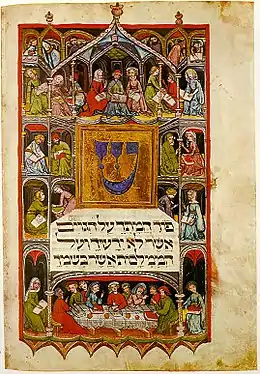

Illuminated manuscripts

The earliest Ashkenazi illuminated Haggada is known as the Birds' Head Haggadah,[37] made in Germany around the 1320s and now in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.[38] The Rylands Haggadah (Rylands Hebrew MS. 6) is one of the finest Haggadot in the world. It was written and illuminated in Spain in the 14th century and is an example of the cross-fertilisation between Jewish and non-Jewish artists within the medium of manuscript illumination. In spring and summer 2012 it was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in the exhibition 'The Rylands Haggadah: Medieval Jewish Art in Context'.[39][40]

The British Library's 14th century Barcelona Haggadah (BL Add. MS 14761) is one of the most richly pictorial of all Jewish texts. Meant to accompany the Passover eve service and festive meal, it was also a status symbol for its owner in 14th-century Spain. Nearly all its folios are filled with miniatures depicting Passover rituals, Biblical and Midrashic episodes, and symbolic foods. A facsimile edition was published by Facsimile Editions of London in 1992.

Published in 1526, the Prague Haggadah is known for its attention to detail in lettering and introducing many of the themes still found in modern texts. Although illustrations had often been a part of the Haggadah, it was not until the Prague Haggadah that they were used extensively in a printed text. The Haggadah features over sixty woodcut illustrations picturing "scenes and symbols of the Passover ritual; [...] biblical and rabbinic elements that actually appear in the Haggadah text; and scenes and figures from biblical or other sources that play no role in the Haggadah itself, but have either past or future redemptive associations".[41]

Other illuminated Haggadot include the Sarajevo Haggadah, Washington Haggadah, and the 20th-century Szyk Haggadah.

References

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100001

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100002/1

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100003/1

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100004/1

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100005

- "Judaism 101: Pesach Seder: How is This Night Different". Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- Talmud Bavli, Pesachim, 116a

- It is very probable that already during the confrontation with the pharaoh the case of the four sons was presented: the wicked is by definition the Pharaoh since he does not want to accept neither God nor His word; the wise is clearly Mosheh, defined precisely also Mosheh Rabbenu, "Mosheh, our Master"; who must be initiated is Job: it is said that Job's fault, precisely in the historical period of the Exodus, was that of having been silent during the rebellion of the Pharaoh against the two leaders of the Jewish people Mosheh and Aaron. Thus Aaron: he is simple in that with facilitated investigative capacity...

- Bazak, Rav Amnon. "The Four Sons". Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash. David Silverberg (trans.). Alon Shvut, Israel: Yeshivat Har Etzion. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "CSJO: Fifth Child". Congress of Secular Jewish Organizations. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "The Fifth Son". Chabad.org. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100019

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100020

- Scherman, Nosson; Zlotowitz, Meir, eds. (1994) [1981]. The Family Haggadah. Mesorah Publications, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-89906-178-8.

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100021

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100022

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100023

- "Chabad.org: 11. Shulchan Orech – set the table". Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100024

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100025

- Eisenberg, Joyce; Scolnic, Ellen (2006). Dictionary of Jewish Words. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Jewish Publication Society. p. 108.

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100029

- This section is based on https://www.themercava.com/app/books/source/1100033

- Pesachim 116a

- See Pesachim 116a

- See Tosafot Bava Batra 46b, who states that every time the Talmud says Rav Nachman it is Rav Nachman bar Yaakov

- See Rashi

- Taub, Jonathan; Shaw, Yisroel (1993). The Malbim Haggadah. Targum Press. ISBN 978-1-56871-007-5.

- Pesachim 116a

- Pesachim 34b

- Hagadah Ḳaraimtsa ṿe-Rustsa = Povi︠e︡stvovanīe na Paskhu po-karaimski i po-russki, Abraham Firkowitsch, Vilʹna : Tip. I. T︠S︡īonsona, 1907

- Passover Haggadah according to the custom of the Karaite Jews of Egypt / [Hagadah shel Pesaḥ : ke-minhag ha-Yehudim ha-Ḳaraʼim] = Passover haggadah : according to the custom of the Karaite Jews of Egypt, edited by Y. Yaron; translation by A. Qanai̤, Pleasanton, CA: Karaite Jews of America, 2000

- זבח קרבן הפסח : הגדה של פסח, נוסח שומרוני (Samaritan Haggada & Pessah Passover / Zevaḥ ḳorban ha-Pesaḥ : Hagadah shel Pesaḥ, nusaḥ Shomroni = Samaritan Haggada & Pessah Passover), Avraham Nur Tsedaḳah, Tel Aviv, 1958

- Mann, Vivian B., "Observations on the Biblical Miniatures in Spanish Haggadot", p.167, in Exodus in the Jewish Experience: Echoes and Reverberations, Editors, Pamela Barmash, W. David Nelson, 2015, Lexington Books, ISBN 1-4985-0293-8, 978-1498502931, google books

- Yerushalmi pp. 23–24

- Cohen, Anne (23 March 2013). "101 Years of the Maxwell House Haggadah". Forward.com. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "Letter to the Editor". Commentary Magazine. August 1969. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- "Birds' Head Haggadah, Germany, 1300". Jerusalem: The Israel Museum. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Rylands Haggadah in New York; John Rylands University Library". Library.manchester.ac.uk. 26 March 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- "Hebrew manuscripts; the John Rylands Library". Library.manchester.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- Yerushalmi p. 34

Bibliography

- Schneerson, Rabbi Menachem M. (1946), Haggadah for Passover with Collected Customs and Reasons: Kehot Publication Society

- Scherman, Rabbi Nosson and Zlotowitz, Rabbi Meir, Artscroll youth haggadah: Mesorah Publications (ISBN 0-89906-232-6)

- Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim (1974). Haggadah and History. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 978-0-8276-0046-1.

- Mishkin, Edwin (2010). A Haggadah For The Nonobservant. Raleigh: lulu. ISBN 978-0-557-28494-8.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Passover Haggadah/Kadesh |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haggadah. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Haggada". |

- Haggadot.com: Let's Make Your Passover Haggadah Together

- My Jewish Learning: The Haggadah

- The Hagada – Peninei Halakha, HaRav Eliezer Melamed

- Yale University Haggadah Exhibit – You Shall Tell Your Children

- A Special Collection of Haggadot for Passover at the National Library of Israel

- Several English translations of the Haggadah, hosted by Sefaria