Harriet Robinson Scott

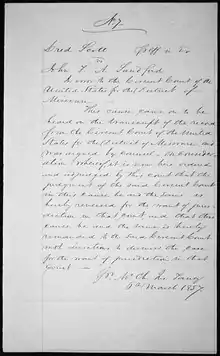

Harriet Robinson Scott (c. 1815 – June 17, 1876) was an African-American woman who fought for her freedom alongside her husband, Dred Scott, in the infamous court case Dred Scott v. Sandford. Decided in 1857, in a court led by chief justice Roger Taney, the case held that a enslaved person had no standing to bring a lawsuit. Born a slave, Robinson Scott traveled from the east coast to the rugged Northwest Territories of modern-day Minnesota, before settling in St. Louis Missouri. After years of effort, Robinson Scott finally attained her freedom in 1857, survived the Civil War and lived out her days in the company of her two daughters and grandchildren.

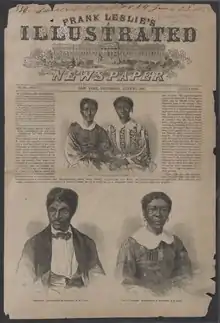

Harriet Robinson Scott | |

|---|---|

Scott c. 1857 | |

| Born | c. 1815 |

| Died | June 17, 1876 (aged c. 61) |

| Resting place | Greenwood Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Dred Scott v. Sandford |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 2 daughters |

Early life

Harriet Robinson Scott was born around 1815 as a slave. As a girl, she was trained as a laundress by her mother, who worked as a slave at an inn.[1] Robinson Scott was never taught to read and remained illiterate throughout her life.[2] By the time Robinson Scott was a teenager, Lawrence Taliaferro, a federal Indian agent, was her owner.[3] While the historical record is unclear, some scholarship suggests that Robinson Scott originated with the Pennsylvania-based family of Taliaferro's wife, Elizabeth Dillon, and was given as a wedding gift to the couple in 1828.[2] However, others believe she originated in Virginia.[4][5] In 1835, Taliaferro was assigned to Fort Snelling, a military post and fur-trading outpost located in present-day Minnesota. Robinson Scott accompanied her owner and was kept as a house slave, serving the Taliaferro household.[6]

Although it violated the Missouri Compromise of 1820, slaves were not uncommon at the newly-built fort and throughout the Northwest Territory. Both local fur traders and military officers held slaves, including Colonel Josiah Snelling himself, with an estimated 30 or more enslaved people living at the fort around the time Robinson Scott moved there.[7] The existence of enslaved people in a region where slavery was legally prohibited occurred in part because military men transferred between slave-owning and free areas.[3] Military officers received an allowance to maintain a servant, however it was not specified that the servant be a free person. Whether they paid their servant a salary or not, they were still allowed to keep the maintenance money. These economic incentives encouraged military officers to supplement their pay by keeping a slave instead of employing a free person. Robinson Scott's owner held additional slaves besides Robinson Scott,[7] usually around 2 to 3 at a time. Records show Taliaferro had about 21 slaves over the course of his life, although in his own note-keeping, he referred to them as "servants."[2]

While slavery was tacitly, if not legally, allowed at the fort, there were examples during this period of enslaved people associated with Fort Snelling becoming free. Sometimes, officers who procured a slave to maintain a household while serving at the fort would free the slave once they returned to their homes in the northeast. Robinson Scott's time at the fort may have overlapped with another slave, Rachel, who would go on to successfully sue for freedom in the mid-1830s.[2]

Marriage to Dred Scott

Robinson Scott lived among and worked within a diverse community. Fort Snelling was a frontier area, where white military men, enslaved and free African-Americans, Native Americans, fur traders and mixed-race people lived in the community. Dakota and Ojibwe tribe members were the largest demographic, and racial dynamics were somewhat more fluid than in other areas, in part because there was no cash-crop economy dependent on slave labor.[8] Winters were very harsh, necessitating close quarters, so there were fewer boundaries between people of different races and classes.[9] While there, Robinson Scott met her future husband, Dred Scott. Scott was a personal slave to Dr. John Emerson who was a military surgeon.[3] Although an enslaved person, Scott was also able to hire himself out and earned some independent income.[8] Harriet Robinson married Dred Scott in 1836 when she was in her late teens or early twenties and he was about 15 years older. It was a second marriage for Scott.[10]

The marriage between the two slaves was particularly notable at the time because an actual civil ceremony took place, officiated over by Robinson Scott's owner, Taliaferro, a justice of the peace. Slave marriages were not recognized as valid at the time for several reasons, including that slaves were generally not allowed to enter into contracts, and the fear that they could then claim additional rights that would undermine the property rights of their owners. The fact that an official ceremony took place was an important point in the subsequent trial, because it suggested that both Emerson and Taliaferro might have recognized the Scotts as free people at the time of their marriage. According to an interview Taliaferro gave around 1864, he was responsible for "marrying the two and giving the girl her freedom." Whether this was really the case is unclear, and others believe that Robinson Scott was sold to Emerson, however no record of a sale has ever been found. Since the Scotts continued to work for, and be hired out by, Emerson following their marriage, they did not live as free people.[11]

Life in slavery

John Emerson was transferred to Fort Jesup in Louisiana by November 1837. There, he met and married Eliza Irene Sanford in February 1838. Shortly thereafter, he sent for the Scotts to join them. In April 1838, Robinson Scott, pregnant with her first child, and her husband traveled to Louisiana, a slave-holding state. By September, Emerson was transferred back to Fort Snelling.[11] By this point, Robinson Scott was heavily pregnant. She gave birth aboard the Gypsey, traveling north on the Mississippi River. The Gypsey was little more than a tug boat, and the Scotts were quartered in the bowels of the ship, near the furnace. Robinson Scott bore a baby girl, named Eliza, north of the Missouri line. This would become an additional point in their subsequent legal argument for freedom. At one point, Emerson became embroiled in a dispute with the Fort Snelling quartermaster, who refused to provide a second stove for the Scott family to use. Emerson obtained the second stove after threatening to fight the man.[6]

In 1840, Emerson was transferred to Florida, and left his wife and the Scott family in St. Louis, Missouri. They stayed with Irene Emerson's father, Alexander Sanford, on his plantation California. Sanford owned an additional four slaves. The Scotts were hired out to work for others in the surrounding area. After Emerson was discharged from the army in 1842, he moved with his wife onto some land he owned in Iowa. Emerson did not live long, dying in 1843 from consumption (tuberculosis). It is unclear whether Robinson Scott lived in Iowa or remained in St Louis.[12] Meanwhile, Robinson Scott gave birth to another girl, named Lizzie.[3][12] Lizzie was born in the slave-state of Missouri.[2] At some point during this period, she also bore two sons, who both died as babies.[2]

After Emerson's death, Irene Emerson moved back to her father's home in St Louis, then east to Massachusetts. She left the Scotts in Missouri under the supervision of her brother-in-law, Captain Henry Bainbridge, during this period.[2] The Scotts continued to live in St Louis through the mid-1840s, hired out to various employers, including a grocery store.[12] In 1846, Dred Scott worked as a valet, accompanying soldiers to Texas during the Mexican-American War.[10]

The case

main article: Dred Scott v. Sandford

Sometime during 1846, Dred Scott offered Irene Emerson $300 in exchange for his family's freedom, but the offer was refused.[10] Lea VanderVelde, author of Mrs Robinson Scott, suggested that Irene Emerson's refusal to free the Scott family and the amount of effort she put into defending her ownership claim in the subsequent trial may have hinged on several calculations. Scott, approaching his mid-fifties, suffering from tuberculosis and no longer able to work as much, would not have been considered a particularly valuable asset any longer. However, Missouri law at the time financially penalized slave-owners who freed old, infirm or very young slaves to fend for themselves. Emerson may have feared paying these penalties.[2] In contrast, Robinson Scott, who was much younger and healthier than her husband, and her two daughters, were considered valuable property. Emerson may have felt that the $300 payment was not enough.[9]

Around the time of the lawsuit, Emerson had largely left the Scotts to fend for themselves. Scott marshaled some support from his former owners, the Blow family, while Robinson Scott became associated with a local church. Emerson's lack of oversight during this time became an issue during the lawsuit when the Scotts had difficulty proving that Emerson was, in fact, their owner. Robinson Scott's membership at the Second African Baptist church in St Louis provided the connection to the Scott's first lawyer, Francis Murdoch, a fellow church member. Murdoch had lived in Bedford, Pennsylvania, around the same time as Robinson Scott's previous owner, Taliaferro, and frequented the same circles. He was familiar with Pennsylvania law. Legal scholars Lea VanderVelde and Sandhya Subramanian suggest that the timing and impetus for the initial case may have hinged on Robinson Scott's origination in Pennsylvania and age at the time, 28 years old. According to Pennsylvania law (An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery), which Murdoch would have been familiar with, Pennsylvania-based slaves would be freed at the age of 28.[2] An additional motivation for the timing of the lawsuit may have been the death of John Emerson, and the fear that, as their Scott daughters grew older, Irene Emerson would sell some or all of the family and split them apart.[13]

Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson Scott separately filed suits for freedom in 1846. Harriet Scott v. Irene Emerson was billeted as the second case for the November court proceedings in St Louis, Missouri, behind her husband's case, Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson. Due to illiteracy, the couple relied on their lawyer, Francis Murdoch, and the minister of the African Baptist church they attended, John R. Anderson, when they filed the petition.[3] The case hinged in part on the "once free, always free" doctrine, which had been established in Missouri court in some prior cases where slaves had successfully sued for freedom. These legal precedents supported the idea that slaves brought to a free state, especially if they lived there for a period of time, could not be re-enslaved.[14]

According to Robinson Scott's great-great granddaughter, Lynne Jackson, filing a separate suit from her husband was important to Robinson Scott, noting "she did that because, as a woman and as the mother, if for any reason Dred did not win his case but she did, then their daughters would be free. There was a little strategy there. And it was courageous."[15]

During the trial and subsequent appeals, Robinson Scott lived at times under the supervision of the St. Louis county sheriff with her husband, and continued working, while the sheriff held onto their pay. However, Robinson Scott's two young daughters remained at large, as the St. Louis Daily Evening News reported after the trial in May 1857:

"[Dred's] daughters, Eliza and Jane [sic], were, virtually, free before, having achieved their freedom by their heels what the more conscientious Dred could not secure by ten years of litigation. Their whereabouts have been kept a secret, though no effort has been, and none probably would have been, made to recover them. Their father knew where they were, and could bring them back at any moment. He will doubtless recall them now."[2]

The Scotts' first lawyer, Murdoch, moved to California before the initial lawsuits could reach trial, leaving them without legal representation. The Blow family assisted the Scotts: their second lawyer was Charles Drake, son-in-law to Dred Scott's former owner, Peter Blow.[16] In 1847, the initial lawsuits were dismissed because the Scotts were not able to prove that Irene Emerson was actually their owner, however the case was re-filed and they were able to establish ownership.[17] The Scott family was granted their freedom on January 12, 1850 by a St. Louis jury.[3]

However, Emerson appealed their case and the court combined the two petitions into one, creating the case Dred Scott vs. Irene Emerson to decide the whole family's fate. In 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the lower court's decision, re-enslaving the Scotts.[18] In 1853, the Scotts appealed the case. Emerson transferred responsibility for the Scotts to her brother, John Sanford (incorrectly spelled Sandford on some court documents); hence the final case was known as Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Sanford appeared to have strong opinions about the Scott family. He called them "worthless and insolent" and physically attacked Robinson Scott and her two daughters in 1853, at one point imprisoning them in a barn.[19]

Five years later, on March 6, 1857, after the case had moved through the United States Supreme Court, the court famously decided the Scott family should remain slaves. The decision hinged on Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's opinion overturning the Missouri Compromise, which had prohibited slavery in certain states. In his opinion, Taney wrote of the assertion that "all men are created equal" in the Declaration of Independence: "it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration."[20]

Some modern legal scholars question the wisdom of combining Harriet Robinson Scott's case with her husband's, noting that several details of her life meant she had the stronger claim to freedom, and a positive result would have freed not only Robinson Scott, but also her two daughters (since slave status flowed from the mother). Potential legal avenues Robinson Scott might have had available to her that did not apply to her husband included her origins in Pennsylvania, a free state with laws requiring manumission of enslaved people at age 28, and the possibility that her former owner, Taliaferro, intended to free her when he officiated her marriage to Scott.[2]

Life after the trial

Although Robinson Scott lost her case for freedom, she did not remain a slave for long. Irene Emerson, the owner who had fought to keep her enslaved, had since re-married and moved to Massachusetts. Her new husband, Dr. Calvin Clifford Chaffee was a congressman and publicly against slavery.[21] Although Emerson had transferred control of the Scotts to her brother, John Sanford, she remained the legal owner. Chaffee claimed to be unaware that his wife owned some of the most well-known slaves of the era until just before the final decision in the case was handed down. Exposed to censure as a hypocrite, Chaffee asked that ownership of the Scotts be transferred to Taylor Blow. Only a citizen of Missouri could transfer ownership, leaving the decision to his wife. She complied, but demanded, and received, the $750 in wages earned by the Scotts and held by the sheriff over the past years while the trial was ongoing.[22]

On May 26, 1857, the Scotts were officially freed.[23] In the months following the trial, the Scott family had visits from some reporters, looking to learn more about the people behind the famous court case. Some reporters attempted to convince Dred Scott to tour the country, promising he could make $1,000 or more. Robinson Scott was protective of her husband, asking that white men leave her husband alone, and insisting there would be no tour.[24] In part, Robinson Scott was afraid of additional scrutiny and the possibility that she or her family could be kidnapped back into slavery.[10] Robinson Scott did agree to having a daguerreotype made of the couple and her children, on the condition that she would get to keep a copy.[2] Robinson Scott's husband lived only a short time after freedom, dying of tuberculosis in 1858.[12] Robinson Scott continued supporting the family as a laundress, saying in the vernacular of the day that “she’d always been able to yarn her own livin, thank God.”[24]

Robinson Scott lived in St Louis for the remainder of her life. She was listed in the St Louis directory from 1859 to 1876. In the 1860 census she is listed as living in her own home, though by 1870 she was a live-in domestic servant. She died on June 17, 1876, having lived through the Civil War and the emancipation of the slaves.[4]

Descendants and legacy

Robinson Scott's two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, went on to live as free black women. Older daughter Eliza married Wilson Madison. While she may have had seven children, only two sons survived to adulthood. Lizzie did not marry, and lived an obscure existence for much of her adult life. She disguised her identity by taking on an assumed name, Lizzie Marshall. She lived to be nearly 100 years old, dying in 1945. She worked as a cleaner for a boarding house and also helped take care of her nephews.[25]

Robinson Scott has living descendants who remain in Missouri. Lynne Jackson, a great-great granddaughter of the Scotts, founded the Dred Scott Heritage Foundation to promote the historical legacy of the Scotts and encourage racial reconciliation.[26]

Some contemporary accounts of Robinson Scott's husband described him favorably. A former governor of Missouri said at the time that "Scott was a very much respected Negro." In 1857, a St Louis newspaper described Scott as "illiterate but not ignorant," with a "strong common sense."[19]

Following the case and in the ensuing decades, a negative portrait of the Scott family was advanced in some quarters.[27] In a biography of John Emerson, written in 1938 by Charles Snyder, the author quotes a 1929 article by John Hodder stating that "apparently Scott was one of the most shiftless and lazy members of his race. Mrs. Emerson had no use for him, so she allowed him to remain as a hanger-on at the army post and to shift for himself." Snyder proposed that Irene Emerson resisted freeing the Scotts, not because she wished to keep them as slaves, but because she felt she legally could not free them given the terms of her husband's will.[28]

However, in recent years, both Dred and Harriet Scott have received more attention and recognition for their role in the court case and fight for freedom. A re-evaluation of Dred Scott's personal qualities occurred.[29][2] The role and agency of Robinson Scott in the case has received additional attention.[2][1][6]

Robinson Scott was buried in an unmarked grave in the Black-only Greenwood Cemetery in St Louis. Her grave remained forgotten until it was re-discovered in 2006 by Etta Daniels of the Greenwood Cemetery Preservation Association. The cemetery was neglected for a time, but by the early 2000's efforts were made to reclaim the lost graves. Volunteers raised funds to place a marker and memorialize Robinson Scott's final resting place.[15]

In recent years, descendants of Robinson Scott met with those of Judge Taney to receive a public apology, which was accepted. The combined group has worked together to determine what should happen to memorial statues of Taney.[30]

References

- "Harriets Story". www.thedredscottfoundation.org. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- VanderVelde, Lea (1997). "Mrs Dred Scott". The Yale Law Journal. 106: 1042–1045, 1056–1058, 1066–1069, 1074, 1084 – via DigitalCommons.

- "Harriet Robinson Scott - Historic Missourians - The State Historical Society of Missouri". shsmo.org. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- "Harriet Robinson Scott - Historic Missourians - The State Historical Society of Missouri". historicmissourians.shsmo.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Harriets Story". www.thedredscottfoundation.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Harriet Scott played her own pivotal role in landmark 1857 Supreme Court case". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- "Enslaved African Americans and the Fight for Freedom". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- "Dred and Harriet Scott in Minnesota | MNopedia". www.mnopedia.org. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Stern, Scott W. (2019-09-05). "The Forgotten Women of Abolitionism". Chicago Review of Books. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Lewis, David (2014-01-11). "Harriet Robinson Scott (ca. 1820-1876)". Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Schofield & Dixon (2007-03-02). "Dred Scott and the election of Lincoln in 1860" (PDF). polisci.wustl.edu.

- "Dred Scott Case, 1846–1857". Missouri Digital Heritage. Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- "March 6, 1857: Dred (and Harriet) Scott Decision". Zinn Education Project. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "The Revised Dred Scott Case Collection". digital.wustl.edu. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Why are Dred and Harriet Scott buried in different cemeteries? Curious Louis finds out". St. Louis Public Radio. 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "DRED SCOTT-Freedom Suit". www.umsl.edu. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Dred Scott". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Editors, History com. "Dred Scott Decision". HISTORY. Retrieved 2020-09-26.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Balkin, Jack (2007). Thirteen ways of looking at Dred Scott (PDF). Chicago-Kent Law Review.

- "Dred Scott case". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Dred Scott - Historic Missourians - The State Historical Society of Missouri". historicmissourians.shsmo.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Dred Scott | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "Missouri Digital Heritage: Dred Scott Case, 1846-1857". www.sos.mo.gov. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Arenson, Adam. "Freeing Dred Scott". Commonplace. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Klinkenberg, Dean (2020-02-09). "The Lives of Dred and Harriet Scott". Mississippi Valley Traveler. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- "The Foundation". Dred Scott Lives. 2019-06-24. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Johnson, Pauline Copes. "Pauline Copes Johnson: Dred Scott was a pioneer for freedom". Auburn Citizen. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Snyder, Charles (1938). John Emerson, Owner of Dred Scott. The Annals of Iowa.

- News, Deseret (2009-11-03). "Shurtleff launches campaign ... for his novel". Deseret News. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Pitts, Jonathan M. "Roger Taney, Dred Scott families reconcile 160 years after infamous Supreme Court decision". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

Further reading

- William D. Green (2007). A Peculiar Imbalance: The Fall and Rise of Racial Equality in Early Minnesota. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 9780873515863.