Heart Mountain Relocation Center

The Heart Mountain War Relocation Center, named after nearby Heart Mountain and located midway between the towns of Cody and Powell in northwest Wyoming, was one of ten concentration camps used for the internment of Japanese Americans evicted from the West Coast Exclusion Zone during World War II by executive order from President Franklin Roosevelt after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, upon the recommendation of Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt.

Heart Mountain Concentration Camp | |

Heart Mountain historical marker and mountain behind. | |

| Location | Park County, Wyoming, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Ralston, Wyoming |

| Coordinates | 44°40′18″N 108°56′47″W |

| Built | 1942 |

| Architect | US Army Corps of Engineers; Hazra Engineering; Hamilton Br. Co. |

| NRHP reference No. | 85003167 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 19, 1985[1] |

| Designated NHL | September 20, 2006[2] |

This site was managed before the war by the federal Bureau of Reclamation for a major irrigation project. Construction of the 650 military-style barracks and surrounding guard towers began in June 1942, and the camp opened on August 11, when the first Japanese Americans arrived by train from the Pomona, Santa Anita, and Portland assembly centers. The camp would hold a total of 13,997 Japanese Americans over the next three years, with a peak population of 10,767, making it the third-largest "town" in Wyoming before it closed on November 10, 1945.[3]

Heart Mountain is best known for many of its younger residents' challenging the controversial draft of Nisei males from camp in order to highlight the loss of their rights through the incarceration. The Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, led by Frank Emi and several others, was particularly active in this resistance, encouraging internees to refuse military induction until they and their families were released from camp and had their civil rights restored. Heart Mountain had the highest rate of draft resistance of all ten camps, with 85 young men and seven Fair Play Committee leaders ultimately sentenced and imprisoned for Selective Service Act violations.[4] (At the same time, 649 Japanese American men[5] — volunteers and draftees — joined the American military from Heart Mountain. In 1944, internees dedicated an Honor Roll listing the names of these soldiers, located near the camp's main gate.)

In 1988 and 1992 Congress passed laws to apologize to Japanese Americans for the injustices during the war and to pay compensation to survivors of the camps and their descendants. The site of the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center is considered to retain the highest integrity of the ten incarceration centers constructed during World War II. The street grid and numerous foundations are still visible. Four of the original barracks survive in place. A number of others sold and moved after the war have been identified in surrounding counties and may one day be returned to their original locations. In early 2007, 124 acres (50.2 ha) of the center were listed as a National Historic Landmark. The Federal Bureau of Reclamation owns 74 acres (29.9 ha) within the landmark boundary and currently administers the site. The remaining 50 acres (20.2 ha) were purchased by the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, a nonprofit organization established in 1996 to memorialize the center's internees and to interpret the site's historical significance.

The Foundation runs the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center, opened in 2011, located at 1539 Road 19, Powell.[6] The museum includes photographs, artifacts, oral histories and interactive exhibits about the wartime relocation of Japanese Americans, anti-Asian prejudice in America and the factors leading to their enforced relocation and confinement.

Establishing the camp

Pre-war history

The land that would become the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center was originally part of the Shoshone Project, an irrigation project under the auspices of the Bureau of Reclamation. In 1897, 120,000 acres (48,562.3 ha) of land surrounding the Shoshone River in northwestern Wyoming was purchased by William "Buffalo Bill" Cody and Nate Salisbury, who in May 1899 acquired water rights to irrigate 60,000 acres (24,281.1 ha) surrounding Cody, Wyoming.[7] After the project proved too costly for the original investors, the Wyoming State Board of Land Commissioners petitioned the federal government to take it over. The rights for the Cody-Salisbury tract were transferred to the Secretary of the Interior in 1904 and the Shoshone Project was approved later that year as one of the earliest Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) projects.[7][8]

In 1937 during the Great Depression, the BOR used private contractors and Civilian Conservation Corps laborers to begin construction on the Shoshone Canyon Conduit and the Heart Mountain Canal, as one of a number of governmental infrastructure projects. The conduit, spanning 2.8 miles, was completed in September 1938. Construction on the unfinished canal stopped after the United States entered World War II.[3][9]

Executive Order 9066

Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized military commanders to create zones from which "any or all persons may be excluded." The War Department had requested this and designated Western Washington and Oregon, southern Arizona, and all of California as Exclusion Zones on March 2, 1942. Four days later, the executive order informally extended to Alaska, covering the entire West Coast of the United States.[10] It defined Japanese Americans, Italian Americans and German Americans as peoples to be excluded from these areas. Soon after the War Department initiated the removal of over 110,000 Japanese Americans from these areas, forcing them into temporary "assembly centers" run by the Wartime Civil Control Administration. Typically, these centers were hastily converted large public spaces, such as fairgrounds and horse racing tracks, while construction on Heart Mountain and the other more permanent "relocation centers" were completed.

Building Heart Mountain

On May 23, 1942, the War Department announced that one of the camps for displaced Japanese Americans would be located in Wyoming, and several communities, hoping to capitalize on internee labor for irrigation and land development projects, vied for the site.[8] Heart Mountain was chosen because it was remote yet convenient, isolated from the nearest towns but close to fresh water and adjacent to a railroad spur and depot where Japanese Americans, as well as food and supplies, could be off-loaded.[3]

On June 1, 1942, the Bureau of Reclamation transferred 46,000 acres (18,615.5 ha) of the Heart Mountain Irrigation Project and several CCC buildings to the War Relocation Authority, the branch of the Western Defense Command responsible for administration of the incarceration program.[3][11] More than 2,000 laborers, including men employed by the Harza Engineering Company of Chicago and the Hamilton Bridge Company of Kansas City, began work on June 8, under the direction of the Army Corps of Engineers.[8] The workers enclosed 740 acres (299.5 ha) of arid buffalo grass and sagebrush with a high barbed wire fence and nine guard towers. Within this perimeter, 650 military-style barracks were laid out in a street grid, with administrative, hospital, educational, and utility facilities, and 468 residential dormitories to house the internees.[8]

All of the buildings were electrified, which was at the time a rarity in Wyoming, but due to time constraints and a largely unskilled workforce, the majority of these "buildings" were poorly constructed. Army higher-ups gave the site's chief engineer only sixty days to complete the project, and newspaper ads recruiting laborers promised jobs "if you can drive a nail" while workers boasted that it took them only 58 minutes to build an apartment barracks.[3][8] Thousands of acres of surrounding land were designated for agricultural purposes, as the center was expected for the most part to be self-sufficient.

World War II

Life in camp

The first inmates arrived in Heart Mountain on August 12, 1942: 6,448 from Los Angeles County; 2,572 from Santa Clara County; 678 from San Francisco; and 843 from Yakima County in Washington.[11] After being assigned a barracks based on the size of their families, they began making small improvements on their new "apartments," hanging bed sheets to create extra "rooms," and stuffing newspaper and rags into cracks in the shoddily constructed walls and floors to keep out dust and cold.[3] Some inmates went so far as to order tools from Sears & Roebuck catalogs in order to make repairs.[12] Each barracks unit contained one light, a wood-burning stove, and an army cot and two blankets for each member of the family. Bathrooms and laundry facilities were located in shared utility halls, and meals were served in communal mess halls, both assigned by block. Armed military police manned the nine guard towers surrounding the camp.

Leadership positions in Heart Mountain were occupied by European-American administrators, although Nisei block managers and Issei councilmen were elected by the inmate population and participated, in a limited capacity, in administration of the camp.[3] Employment opportunities were available in the hospital, camp schools and mess halls, as well as the garment factory, cabinet shop, sawmill and silk screen shop run by camp officials, although most inmates received a rather paltry salary of $12–$19 a month, due to the WRA's decision that the Japanese could not earn more than an army private regardless of job.[3][11] (Caucasian nurses in the Heart Mountain hospital, for example, were paid $150/month compared to the $19/month given Japanese-American doctors)[11][12] Additionally, some inmates worked on the unfinished Heart Mountain Canal for the Bureau of Reclamation, or did agricultural work outside the camp.

Children of inmates began school in barrack classrooms in October 1942. Books, school supplies, and furniture were limited. Despite the poor condition of the facilities, attending school offered a sense of normalcy to camp children. In May 1943, the camp high school had been constructed, and the elementary school restructured. The high school, which educated 1,500 students in its first year, featured regular classrooms, a gymnasium and library. Its sports team, including its football team, The Heart Mountain Eagles, eventually competed against other local high school teams.[13]

Other sporting events, movie theaters, religious services, crafting groups, and social clubs kept inmates entertained and provided a distraction from the dullness of camp life. Knitting, sewing, and woodcarving were popular not only for entertainment, but because they allowed inmates to improve their dilapidated living conditions. Among children, Girl and Boy Scout programs flourished, as many Nisei had been members before internment. Heart Mountain's thirteen scout troops and two Cub Scout packs were the most of any of the ten camps.[3][11][14] Scouts participated in normal scouting activities such as hiking, craft making, and swimming.

Draft resistance

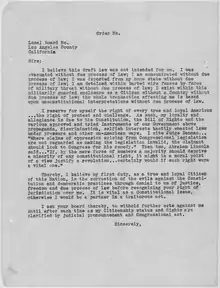

In early 1943, camp officials began to administer a "Leave Clearance Form," better known as the loyalty questionnaire because of two controversial questions that tried to distinguish loyal and disloyal Japanese Americans. Question 27 asked whether men would be willing to serve in the armed forces, while Question 28 asked inmates to forswear all allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Many, confused by the questionnaire's wording, fearing it was a trick and any answer would be misconstrued, or, offended by the questions' implications, answered "no" to one or both questions, or gave a qualified response like, "I will serve when I am free." Soon after, Kiyoshi Okamoto organized the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee to protest the infringement of Nisei citizen rights, and Frank Emi, Paul Nakadate and others began posting fliers around camp encouraging others not to respond to the questions.[15]

When draft orders began arriving in Heart Mountain, Emi, Okamoto and the other leaders of the Fair Play Committee held public meetings to discuss the unconstitutionality of the incarceration and encourage other inmates to refuse military service until their freedom was restored. On March 25, 1944, twelve Heart Mountain resisters who had not reported for their draft physicals were arrested by U.S. Marshals. Emi and two other Committee members who had not received draft notices (due to their age or domestic status) tried to walk out of camp to highlight their status as prisoners of the government.[15]

In July 1944, in the largest mass trial in Wyoming history, sixty-three Heart Mountain inmates were prosecuted after refusing to show up for their induction and convicted of felony draft evasion.[11][16] A total of 300 draft resisters from eight WRA camps, including an additional 22 from Heart Mountain sentenced in a subsequent trial, were arrested for this charge, and most served time in federal prison.[17] The seven older leaders of the Fair Play Committee were convicted of conspiracy to violate the Selective Service Act and sentenced to four years in federal prison.[16] While the Poston concentration camp in Arizona had the highest number of resisters of any camp, at 106, Heart Mountain's 85 resisters from a much smaller population gave it the highest overall rate of draft resistance.[4]

Although Heart Mountain is remembered primarily for its organized resistance to the draft, approximately 650 Nisei[18] joined the U.S. Army from this camp, either volunteering or accepting their conscription into the legendary 100th Infantry Battalion,[19] the famed 442nd RCT[20] and MIS.[21] Fifteen of these young men were killed in action and fifty-two wounded. Joe Hayashi and James K. Okubo posthumously received the Medal of Honor for valor in battle, making Heart Mountain the only one of the ten WRA camps to have more than one Medal of Honor recipient.[11] In late 1944, camp inmates erected an Honor Roll in front of the administration building listing the names of these soldiers. This wooden tribute stood for five decades, until the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation removed the deteriorating display for preservation. An accurate reproduction, completed in 2003, now stands in place of the original.[22] The original Honor Roll is being conserved and restored.

The end of the war

By the time Roosevelt rescinded Executive Order 9066 in December 1944 and announced that Japanese Americans could begin returning to the West Coast the following month, many had already left camp, most for outside work or to attend college in the Midwest or East Coast. Beginning in January 1945, internees began to leave Heart Mountain for the West Coast, provided by administrators with $25 and a one-way train ticket to the location they had been picked up from three years earlier.[11] However, even with the earlier group of resettlers, only 2,000 had left by June 1945, and the 7,000 still remaining within Heart Mountain for the most part represented those who were too young or too old to easily relocate.[12] Many Japanese Americans, barred from owning their pre-war homes and farms by discriminatory legislation, had nothing to return to on the West Coast, but they were prohibited from homesteading in Wyoming by an alien land law passed by the state legislature in 1943 (a law that remained in place until 2001).[3] Another Wyoming law excluding them from voting further discouraged Japanese Americans from staying in Wyoming.[11] The last trainload of former inmates left Heart Mountain on November 10, 1945.[3][12]

Preservation and remembrance

After Heart Mountain closed, most of the land, barracks and agricultural equipment were sold to farmers and former servicemen, who established homesteads on and around the camp site.[3][11] The Heart Mountain Irrigation Project continued after the war, and much of the camp's surrounding acreage was tilled for irrigation agriculture. Remnants of the hospital complex (including foundations and 3 buildings), a Heart Mountain High School storage shed, a root cellar, the Honor Roll World War II Memorial and a portion of a remodeled barrack are the only buildings still standing today.

The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, established in 1996, has worked to preserve and memorialize the site and events, educate the general public about the Japanese American incarceration, and support research about the incarceration so that future generations can understand the lessons of the Japanese American incarceration experience. The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation is overseen by a 16-member Board of Directors and is led by the Chair, Shirley Ann Higuchi, a descendant of former internees. The board also includes former internees, scholars, and other professionals working on the local and national level. The Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation gained National Historic Landmark status for the site in 2007 and on August 20, 2011 opened the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center.[23][24][25] The Center features a permanent exhibit that provides an overview of the history of the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans and the background of anti-Asian prejudice in America that led to it. Along with additional rotating exhibits, these photographs, artifacts and oral histories explore the incarceration experience, constitutional and civil rights issues, and the broader issues of race and social justice in America. Visitors can also participate in a walking tour of the site and its remaining structures. Former U.S. Secretary of Transportation Norman Y. Mineta and retired U.S. Senator Alan K. Simpson, who met as Boy Scouts on opposite sides of the barbed wire fence surrounding the Heart Mountain compound, act as Honorary Advisors to the Foundation.[26][27]

The Foundation hosts an annual pilgrimage at Heart Mountain, the first of which coincided with the Interpretive Center's 2011 opening.[28]

Terminology

Since the end of World War II, there has been debate over the terminology used to refer to Heart Mountain and the other camps in which Japanese Americans were incarcerated by the United States Government during the war.[29][30][31] Heart Mountain has been referred to as a "War Relocation Center," "relocation camp," "relocation center," "internment camp," "incarceration camp," and "concentration camp," and the controversy over which term is the most accurate and appropriate continues to the present day.[32][33][34] Scholars and activists both have criticized internment camp as euphemistic, as Japanese Americans were not there for their protection and could not leave.

Notable internees

- Hideo Date (1907–2005), a painter

- Kathryn Doi (born 1942), Associate Justice of the California Second District Court of Appeals.

- Frank S. Emi (1916–2010), Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee leader and civil rights activist.

- Sadamitsu "S. Neil" Fujita (1921–2010), graphic designer who served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

- Evelyn Nakano Glenn (born 1940), a professor of Gender & Women Studies and of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley and founding director of the Center for Race and Gender (CRG). Also interned at Gila River.

- Mary Matsuda Gruenewald (born 1925), memoirist. Also interned at Tule Lake.

- Joe Hayashi (1920–1945), 442nd RCT volunteer posthumously awarded Medal of Honor.

- Bill Hosokawa (1915–2007), author and journalist, editor of the camp newspaper "Heart Mountain Sentinel."[35]

- Estelle Ishigo (née Peck) (1899–1990), an American artist married to a Nisei.

- George Ishiyama (1914–2003), businessman and former president of Alaska Pulp Corporation. Also interned at Topaz.

- Hikaru Iwasaki (1923–2016), an American photographer .

- Lincoln Kanai (1908—1982), social worker and civil rights activist who brought a legal challenge to the eviction of Japanese Americans from the West Coast.

- Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943–2000), an author and civil and social justice advocate.

- Yosh Kuromiya (1923-2018), Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee member who resisted the draft on constitutional grounds and promoted understanding of the Nisei draft resisters in film and public forums.

- Robert Kuwahara (1901–1964), animator.

- Norman Mineta (born 1931), United States Secretary of Transportation under George W. Bush and United States Secretary of Commerce under Bill Clinton.[36]

- Lane Nakano (1925–2005), American soldier turned actor

- Fusataro Nakaya (born 1886), medical doctor (1916 graduate of University of Illinois Medical College), member of California Medical Association, Vice President of Los Angeles Japanese Association

- Shigeki Oka (1878–1959), Issei newspaper publisher who was recruited by the British Armed Forces in World War II.

- Benji Okubo (1904–1975), an American painter, teacher, and landscape designer.

- James K. Okubo (1920–1967), 442nd RCT veteran posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Also interned at Tule Lake.

- Albert Saijo (1926–2011), poet

- Nyogen Senzaki (1876–1958), Rinzai Zen monk who was one of the 20th century's leading proponents of Zen Buddhism in the United States.

- Teiko Tomita (1896–1990), a tanka poet. Also interned at Tule Lake.

- Otto Yamaoka (1904–1967), an American actor and businessman who worked in Hollywood during the 1930s

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heart Mountain War Relocation Center. |

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "Heart Mountain Relocation Center". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- Matsumoto, Mieko. "Heart Mountain Archived February 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine," Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- Muller, Eric L. "Draft resistance Archived March 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine," Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- https://www.dropbox.com/sh/2nihl23t9tg7uxv/AAAUYc2PkAR72q99FMxy7jGfa/14)%20SOLDIERS%20AND%20CAMPS?dl=0&preview=!SOLDIERS+AND+THE+CAMPS+(Alphabetical)+646B.pdf&subfolder_nav_tracking=1

- Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation. "The Heart Mountain Interpretive Center Archived May 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- Stene, Eric A. "Shoshone Project History Archived May 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine," (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 1996), p 3.

- Miyagishima, Kara M. "National Historic Landmark Nomination Archived May 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine" (National Park Service, November 2004). Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- Stene, Eric A. "Shoshone Project History Archived May 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine," pp 14-17

- "Chapter V: Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast, page 143". Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, "Life in Camp Archived March 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine" Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- Mackey, Mike. "A Brief History of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center and the Japanese American Experience Archived August 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- "Life in Camp". Archived from the original on March 29, 2019.

- "Scouting in World War II Detention Camps". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- Newman, Esther. "Frank Emi Archived April 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine," Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- Muller, Eric L. "Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee Archived May 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine," Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- "Conscience and the Constitution: Resistance Archived May 3, 2015, at the Wayback Machine" (PBS). Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- https://www.dropbox.com/sh/2nihl23t9tg7uxv/AAAUYc2PkAR72q99FMxy7jGfa/14)%20SOLDIERS%20AND%20CAMPS?dl=0&preview=!SOLDIERS+AND+THE+CAMPS+(Alphabetical)+646B.pdf&subfolder_nav_tracking=1

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, "About HMWF Archived February 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- Asakawa, Gil (August 18, 2011). "Heart Mountain internment Camp's New Interpretive Learning Center Opens This Weekend". Nikkei View: The Asian American Blog. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- Olson, Ilene (August 23, 2011). "Heart Mountain Lesson: Never Again". Powell Tribune. Archived from the original on September 14, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- Schweigert, Tessa (August 18, 2011). "Returning To Heart Mountain". Powell Tribune. Archived from the original on September 13, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- "Simpson-Mineta Leaders Series". The Washington Center. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- "WASHINGTON TALK: FRIENDSHIPS; The Heat of War Welds A Bond That Endures Across Aisles and Years". The New York Times. April 26, 1988. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- "Heart Mountain Relocation Center Construction Project". The Powered by The People construction Group. March 27, 2012. Archived from the original on May 22, 2015. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- "The Manzanar Controversy". Public Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on February 7, 2005. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- Daniels, Roger (May 2002). "Incarceration of the Japanese Americans: A Sixty-Year Perspective". The History Teacher. 35 (3): 4–6. doi:10.2307/3054440. JSTOR 3054440. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- Ito, Robert (September 15, 1998). "Concentration Camp Or Summer Camp?". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- Reflections: Three Self-Guided Tours Of Manzanar. Manzanar Committee. 1998. pp. iii–iv.

- "CLPEF Resolution Regarding Terminology". Civil Liberties Public Education Fund. 1996. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "Densho: Terminology & Glossary: A Note On Terminology". Densho. 1997. Archived from the original on June 24, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- Broom, Jack (November 14, 2007). "Newsman Bill Hosokawa defeated bias, his own anger". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- Matthews, Chris (2002). "A Pair of Boy Scouts". Scouting Magazine. Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original on May 6, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

External links

- Heart Mountain Relocation Center records, 1943-1945, The Bancroft Library

- Pig pens at Heart Mountain Relocation Center [graphic] / painted by Estelle Ishigo, The Bancroft Library

- Activities and entertainment at Heart Mountain Relocation Center - The Bancroft Library

- Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation - Visitor center site

- Confinement and Ethnicity — National Park Service study on the relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II (out-of-print but can be consulted here for information on Heart Mountain and all ten relocation centers)

- Heart Mountain Digital Preservation Project — History and photographs from the Hinckley Library, Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming.

- Fact sheet from the US National Park Service

- Images of Heart Mountain Relocation Center by Jack Richard, from Buffalo Bill Historical Center's McCracken Research Library

- Roy Nakata papers on departing the Relocation Center, circa 1939-1945, The Bancroft Library

- Guide to the Heart Mountain War Relocation Papers at the University of Montana Contains publications and other items produced at the Relocation Center

- "Scout troop 379 of Heart Mountain". Boys' Life. December 1970.

- Matsumoto, Mieko. "Densho Encyclopedia: Heart Mountain". encyclopedia.densho.org. Densho. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- Wakida, Patricia. "Densho Encyclopedia: Heart Mountain Sentinel (newspaper)". encyclopedia.densho.org. Densho. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- "The Legacy of Heart Mountain" Documentary about life at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center.