Henry Ward Beecher

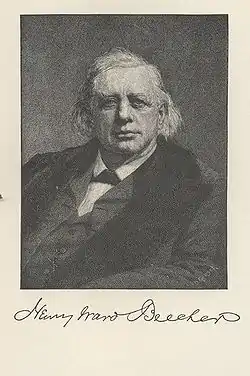

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery trial (see below). His rhetorical focus on Christ's love has influenced mainstream Christianity to this day.

Henry Ward Beecher | |

|---|---|

Beecher, between 1855 and 1865 | |

| Born | June 24, 1813 |

| Died | March 8, 1887 (aged 73) |

| Occupation | Congregational Clergyman, abolitionist |

| Spouse(s) | Eunice White Beecher |

| Parent(s) | Lyman and Roxana Beecher |

| Signature | |

Henry Ward Beecher was the son of Lyman Beecher, a Calvinist minister who became one of the best-known evangelists of his era. Several of his brothers and sisters became well-known educators and activists, most notably Harriet Beecher Stowe, who achieved worldwide fame with her abolitionist novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. Henry Ward Beecher graduated from Amherst College in 1834 and Lane Theological Seminary in 1837 before serving as a minister in Indianapolis and Lawrenceburg, Indiana.

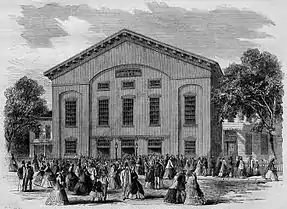

In 1847, Beecher became the first pastor of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York. He soon acquired fame on the lecture circuit for his novel oratorical style in which he employed humor, dialect, and slang. Over the course of his ministry, he developed a theology emphasizing God's love above all else. He also grew interested in social reform, particularly the abolitionist movement. In the years leading up to the Civil War, he raised money to purchase slaves from captivity and to send rifles—nicknamed "Beecher's Bibles"—to abolitionists fighting in Kansas. He toured Europe during the Civil War, speaking in support of the Union.

After the war, Beecher supported social reform causes such as women's suffrage and temperance. He also championed Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, stating that it was not incompatible with Christian beliefs.[1] He was widely rumored to be an adulterer, and in 1872 the Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly published a story about his affair with Elizabeth Richards Tilton, the wife of his friend and former co-worker Theodore Tilton. In 1874, Tilton filed charges for "criminal conversation" against Beecher. The subsequent trial resulted in a hung jury and was one of the most widely reported trials of the century.

Beecher's long career in the public spotlight led biographer Debby Applegate to call her biography of him The Most Famous Man in America.[2]

Early life

Beecher was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, the eighth of 13 children born to Lyman Beecher, a Presbyterian preacher from Boston. His siblings included author Harriet Beecher Stowe, educators Catharine Beecher and Thomas K. Beecher, and activists Charles Beecher and Isabella Beecher Hooker, and his father became known as "the father of more brains than any man in America".[3] Beecher's mother Roxana died when Henry was three, and his father married Harriet Porter, whom Henry described as "severe" and subject to bouts of depression.[4] Beecher also taught school for a time in Whitinsville, Massachusetts.

The Beecher household was "the strangest and most interesting combination of fun and seriousness".[5] The family was poor, and Lyman Beecher assigned his children "a heavy schedule of prayer meetings, lectures, and religious services" while banning the theater, dancing, most fiction, and the celebration of birthdays or Christmas.[6] The family's pastimes included story-telling and listening to their father play the fiddle.[7]

Beecher had a childhood stammer. He was also considered slow-witted and one of the less promising of the brilliant Beecher children.[8] His poor performance earned him punishments, such as being forced to sit for hours in the girls' corner wearing a dunce cap.[9] At 14, he began his oratorical training at Mount Pleasant Classical Institute, a boarding school in Amherst, Massachusetts where he met Constantine Fondolaik, a Smyrna Greek. They attended Amherst College together, where they signed a contract pledging lifelong friendship and brotherly love. Fondolaik died of cholera after returning to Greece in 1842, and Beecher named his third son after him.[10]

During his years in Amherst, Beecher had his first taste of public speaking, and he resolved to join the ministry, setting aside his early dream of going to sea.[11][12] He met his future wife Eunice Bullard, the daughter of a well-known physician, and they were engaged on January 2, 1832.[13][14] He also developed an interest in the pseudoscience of phrenology, an attempt to link personality traits with features of the human skull, and he befriended Orson Squire Fowler who became the theory's best-known American proponent.[15]

Beecher graduated from Amherst College in 1834 and then attended Lane Theological Seminary outside Cincinnati, Ohio.[16] Lane was headed by Beecher's father, who had become "America's most famous preacher".[17] The student body was divided by the slavery question, whether to support a form of gradual emancipation, as Lyman Beecher did, or to demand immediate emancipation.[18] Beecher stayed largely clear of the controversy, sympathetic to the radical students but unwilling to defy his father.[19] He graduated in 1837.[20]

Early ministry

On August 3, 1837, Beecher married Eunice Bullard, and the two proceeded to the small, impoverished town of Lawrenceburg, Indiana, where Beecher had been offered a post as a minister of the First Presbyterian Church.[21] He received his first national publicity when he became involved in the break between "New School" and "Old School" Presbyterianism, which were split over questions of original sin and the slavery issue; Henry's father Lyman was a leading proponent of the New School.[22] Because of Henry's adherence to the New School position, the Old School-dominated presbytery declined to install him as the pastor, and the resulting controversy split the western Presbyterian Church into rival synods.[23]

Though Henry Beecher's Lawrenceburg church declared its independence from the Synod to retain him as its pastor, the poverty that followed the Panic of 1837 caused him to look for a new position.[24] Banker Samuel Merrill invited Beecher to visit Indianapolis in 1839, and he was offered the ministry of the Second Presbyterian Church there on May 13, 1839.[25] Unusually for a speaker of his era, Beecher would use humor and informal language including dialect and slang as he preached.[26] His preaching was a major success, building Second Presbyterian into the largest church in the city, and he also led a successful revival meeting in nearby Terre Haute.[27] However, mounting debt led to Beecher again seeking a new position in 1847, and he accepted the invitation of businessman Henry Bowen to head a new Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York.[28] Beecher's national fame continued to grow, and he took to the lecture circuit, becoming one of the most popular speakers in the country and charging correspondingly high fees.[29]

In the course of his preaching, Henry Ward Beecher came to reject his father Lyman's theology, which "combined the old belief that 'human fate was preordained by God's plan' with a faith in the capacity of rational men and women to purge society of its sinful ways".[2] Henry instead preached a "Gospel of Love" that emphasized God's absolute love rather than human sinfulness, and doubted the existence of Hell.[16][14] He also rejected his father's prohibitions against various leisure activities as distractions from a holy life, stating instead that "Man was made for enjoyment".[2]

Social and political activism

Abolitionism

Henry Ward Beecher became involved in many social issues of his day, most notably abolition. Though Beecher hated slavery as early as his seminary days, his views were generally more moderate than those of abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, who advocated the breakup of the Union if it would also mean the end of slavery. A personal turning point for Beecher came in October 1848 when he learned of two escaped young female slaves who had been recaptured; their father had been offered the chance to ransom them from captivity, and appealed to Beecher to help raise funds. Beecher raised over two thousand dollars to secure the girls' freedom. On June 1, 1856, he held another mock slave auction seeking enough contributions to purchase the freedom of a young woman named Sarah.[30]

In his widely reprinted piece "Shall We Compromise", Beecher assailed the Compromise of 1850, a compromise between anti-slavery and pro-slavery forces brokered by Whig Senator Henry Clay. The compromise banned slavery from California and slave-trading from Washington, D.C. at the cost of a stronger Fugitive Slave Act; Beecher objected to the last provision in particular, arguing that it was a Christian's duty to feed and shelter escaped slaves. Slavery and liberty were fundamentally incompatible, Beecher argued, making compromise impossible: "One or the other must die".[31] In 1856, Beecher campaigned for Republican John C. Frémont, the first presidential candidate of the Republican Party; despite Beecher's aid, Frémont lost to Democrat James Buchanan.[32] During the pre-Civil-War conflict in the Kansas Territory, known as "Bloody Kansas", Beecher raised funds to send Sharps rifles to abolitionist forces, stating that the weapons would do more good than "a hundred Bibles". The press subsequently nicknamed the weapons "Beecher's Bibles".[33] Beecher became widely hated in the American South for his abolitionist actions and received numerous death threats.[34]

In 1863, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln sent Beecher on a speaking tour of Europe to build support for the Union cause. Beecher's speeches helped turn European popular sentiment against the rebel Confederate States of America and prevent its recognition by foreign powers.[12][35] At the close of the war in April 1865, Beecher was invited to speak at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, where the first shots of the war had been fired;[12] Lincoln had again personally selected him, stating, "We had better send Beecher down to deliver the address on the occasion of raising the flag because if it had not been for Beecher there would have been no flag to raise."[36]

Other views

.jpg.webp)

Beecher advocated for the temperance movement throughout his career and was a strict teetotaler.[37] Following the Civil War, he also became a leader in the women's suffrage movement.[38] In 1867, he campaigned unsuccessfully to become a delegate to the New York Constitutional Convention of 1867–1868 on a suffrage platform, and in 1869, was elected unanimously as the first president of the American Woman Suffrage Association.[39]

In the Reconstruction Era, Beecher sided with President Andrew Johnson's plan for swift restoration of Southern states to the Union. He believed that captains of industry should be the leaders of society and supported Social Darwinist ideas.[40] During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, he preached strongly against the strikers whose wages had been cut, stating, "Man cannot live by bread alone but the man who cannot live on bread and water is not fit to live," and "If you are being reduced, go down boldly into poverty". His remarks were so unpopular that cries of "Hang Beecher!" became common at labor rallies, and plainclothes detectives protected his church.[41][42]

Influenced by British author Herbert Spencer, Beecher embraced Charles Darwin's theory of evolution in the 1880s, identifying as a "cordial Christian evolutionist".[43] He argued that the theory was in keeping with what Applegate called "the inevitability of progress",[44] seeing a steady march toward perfection as a part of God's plan.[45] In 1885, he wrote Evolution and Religion to expound these views.[12] His sermons and writings helped to gain acceptance for the theory in America.[46]

Beecher was a prominent advocate for allowing Chinese immigration to continue to the US, helping to delay passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act until 1882. He argued that as other American peoples, such as the Irish, had seen a gradual increase in their social standing, a new people was required to do "what we call the menial work", and that the Chinese, "by reason of their training, by the habits of a thousand years, are adapted to do that work."[47]

Personal life

Marriage

Beecher married Eunice Bullard in 1837 after a five-year engagement. Their marriage was not a happy one; as Applegate writes, "within a year of their wedding they embarked on the classic marital cycle of neglect and nagging", marked by Henry's prolonged absences from home.[48] The couple also suffered the deaths of four of their eight children.[40]

Beecher enjoyed the company of women, and rumors of extramarital affairs circulated as early as his Indiana days, when he was believed to have had an affair with a young member of his congregation.[49] In 1858, the Brooklyn Eagle wrote a story accusing him of an affair with another young church member who had later become a prostitute.[49] The wife of Beecher's patron and editor, Henry Bowen, confessed on her deathbed to her husband of an affair with Beecher; Bowen concealed the incident during his lifetime.[50]

Several members of Beecher's circle reported that Beecher had had an affair with Edna Dean Proctor, an author with whom he was collaborating on a book of his sermons. The couple's first encounter was the subject of dispute: Beecher reportedly told friends that it had been consensual, while Proctor reportedly told Henry Bowen that Beecher had raped her. Regardless of the initial circumstances, Beecher and Proctor allegedly then carried on their affair for more than a year.[51] According to historian Barry Werth, "it was standard gossip that 'Beecher preaches to seven or eight of his mistresses every Sunday evening.'"[52]

"The Beecher-Tilton Scandal Case" (1875)

In a highly publicized scandal, Beecher was tried on charges that he had committed adultery with a friend's wife, Elizabeth Tilton. In 1870, Elizabeth had confessed to her husband, Theodore Tilton, that she had had a relationship with Beecher.[53] The charges became public after Theodore told Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others of his wife's confession. Stanton repeated the story to fellow women's rights leaders Victoria Woodhull and Isabella Beecher Hooker.[54]

Henry Ward Beecher had publicly denounced Woodhull's advocacy of free love. Outraged at what she saw as his hypocrisy, she published a story titled "The Beecher-Tilton Scandal Case" in her paper Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly on November 2, 1872; the article made detailed allegations that America's most renowned clergyman was secretly practicing the free-love doctrines that he denounced from the pulpit. Woodhull was arrested in New York City and imprisoned for sending obscene material through the mail.[55] The scandal split the Beecher siblings; Harriet and others supported Henry, while Isabella publicly supported Woodhull.[56] The first trial was Woodhull's, who was released on a technicality.[57]

Subsequent hearings and trial, in the words of Walter A. McDougall, "drove Reconstruction off the front pages for two and a half years" and became "the most sensational 'he said, she said' in American history".[57] On October 31, 1873, Plymouth Church excommunicated Theodore Tilton for "slandering" Beecher. The Council of Congregational Churches held a board of inquiry from March 9 to 29, 1874, to investigate the disfellowshipping of Tilton, and censured Plymouth Church for acting against Tilton without first examining the charges against Beecher. As of June 27, 1874, Plymouth Church established its own investigating committee which exonerated Beecher.[58] Tilton then sued Beecher on civil charges of adultery.[59] The Beecher-Tilton trial began in January 1875, and ended in July when the jurors deliberated for six days but were unable to reach a verdict.[60] In February 1876, the Congregational church held a final hearing to exonerate Beecher.[61]

Stanton was outraged by Beecher's repeated exonerations, calling the scandal a "holocaust of womanhood".[61] French author George Sand planned a novel about the affair, but died the following year before it could be written.[62]

Later life and legacy

Later life

In 1871, Yale University established "The Lyman Beecher Lectureship", of which Henry taught the first three annual courses.[12] After the heavy expenses of the trial, Beecher embarked on a lecture tour of the West that returned him to solvency.[63] In 1884, he angered many of his Republican allies when he endorsed Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland for the presidency, arguing that Cleveland should be forgiven for having fathered an illegitimate child.[64] He made another lecture tour of England in 1886.[12]

On March 6, 1887, Beecher suffered a stroke and died in his sleep on March 8. Still a widely popular figure, he was mourned in newspapers and sermons across the country.[61][65] Henry Ward Beecher is interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[66]

Legacy

In assessing Beecher's legacy, Applegate states that

At his best, Beecher represented what remains the most lovable and popular strain of American culture: incurable optimism; can-do enthusiasm; and open-minded, open-hearted pragmatism ... His reputation has been eclipsed by his own success. Mainstream Christianity is so deeply infused with the rhetoric of Christ's love that most Americans can imagine nothing else, and have no appreciation or memory of the revolution wrought by Beecher and his peers.[67]

A Henry Ward Beecher Monument created by the sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward was unveiled on June 24, 1891 in Borough Hall Park, Brooklyn and was later relocated to Cadman Plaza, Brooklyn in 1959.

A limerick written about Beecher by poet Oliver Herford became well known in the USA:[68]

Said a great congregational preacher

To a hen, "You're a beautiful creature."

And the hen, just for that,

Laid an egg in his hat,

And thus did the Hen reward Beecher.— Oliver Herford

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. offered his own limerick on Beecher:[69]

The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher

Called the hen a most elegant creature.

The hen, pleased with that,

Laid an egg in his hat,

And thus did the hen reward Beecher.— Oliver Wendell Holmes

Christopher J Barry, Canadian published songwriter, offered this perhaps more accurate limerick:

The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher

Said of hens: "some are elegant creatures".

Of the hens pleased with that, Some laid eggs in his lap.

What will judgement day hatch for the preacher?— Christopher Joseph Barry

Writings

Background

Henry Ward Beecher was a prolific author as well as speaker. His public writing began in Indiana, where he edited an agricultural journal, The Farmer and Gardener.[12] He was one of the founders and for nearly twenty years an editorial contributor of the New York Independent, a Congregationalist newspaper, and from 1861 till 1863 was its editor. His contributions to this were signed with an asterisk, and many of them were afterward collected and published in 1855 as "Star Papers; or, Experiences of Art and Nature".[12]

In 1865, Robert E. Bonner of the New York Ledger offered Beecher twenty-four thousand dollars to follow his sister's example and compose a novel;[70] the subsequent novel, Norwood, or Village Life in New England, was published in 1868. Beecher stated his intent for Norwood was to present a heroine who is "large of soul, a child of nature, and, although a Christian, yet in childlike sympathy with the truths of God in the natural world, instead of books."[71] McDougall describes the resulting novel as "a New England romance of flowers and bosomy sighs ... 'new theology' that amounted to warmed-over Emerson".[71] The novel was moderately well received by critics of the day.[72]

List of published works

- Seven Lectures to Young Men (1844) (a pamphlet)

- Star Papers (1855)

- Life Thoughts, Gathered from the Extemporaneous Discourses of Henry Ward Beecher by Edna Dean Proctor (1858), Phillips, Sampson and Company, Boston

- Notes from Plymouth Pulpit (1859)

- The Independent (1861–63) (periodical, as editor)

- Eyes and Ears (1862) (collection of letters from the New York Ledger newspaper)

- Freedom and War (1863) Boston, Ticknor and Fields (1863), LCCN 70-157361

- Lectures to Young Men, On Various Important Subjects. New edition with additional lectures. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1868

- Christian Union (1870–78) (periodical, as editor)

- Summer in the Soul (1858)

- Prayers from the Plymouth Pulpit (1867)

- Norwood, or Village Life in New England (1868) (novel)

- Life of Jesus, the Christ (1871) New York: J. B. Ford and Company.

- Yale Lectures on Preaching (1872)

- Evolution and Religion (1885; Reissued by Cambridge University Press 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00045-1)

- Proverbs from Plymouth Pulpit (1887)

- A Biography of Rev. Henry Ward Beecher by Wm C. Beecher and Rev. Samuel Scoville (1888)

See also

Citations

- Henry Ward Beecher (1885). Evolution and Religion. Pilgrim Press.

- Michel Kazin (July 16, 2006). "The Gospel of Love". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- Applegate 2006, p. 264.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 29–31.

- Applegate 2006, p. 28.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 19–20, 27–28.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 28–29.

- Applegate 2006, p. 42.

- Goldsmith 1999, p. 9.

- Hibben, Paxton; Lewis, Sinclair, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, Kessinger Publishing, 2003, p. 32

- Applegate 2006, pp. 69–71.

- Wikisource:Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography/Beecher, Lyman

- Applegate 2006, pp. 84, 90.

- Benfey 2008, p. 68.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 96–97.

- "Henry Ward Beecher". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition. Columbia University Press. 2013.

- Applegate 2006, p. 110.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 104–05, 115–18.

- Applegate 2006, p. 118.

- Applegate 2006, p. 134.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 141–150.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 121–22.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 154–56.

- Applegate 2006, p. 157.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 160–61.

- Applegate 2006, p. 173.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 166, 174–76, 179.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 193–96.

- Applegate 2006, p. 218.

- Shaw, Wayne (2000). "The Plymouth Pulpit: Henry Ward Beecher's Slave Auction Block". ATQ (The American Transcendental Quarterly). 14 (4): 335–43.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 242–43.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 287–88.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 281–82.

- Benfey 2008, p. 69.

- "Beecher Family". Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. Archived from the original on August 23, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- Applegate 2006, p. 6.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 189, 206, 278, 397.

- Morita 2004, p. 62.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 383–84, 387.

- "Henry Ward Beecher – Biography". The European Graduate School. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- Beatty 2008, pp. 296–98.

- Werth 2009, pp. 167–68.

- Werth 2009, p. 260.

- Applegate 2006, p. 461.

- Werth 2009, p. 261.

- Werth 2009, pp. 259–62.

- Gyory 1998, pp. 248–49.

- Applegate 2006, p. 158.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 197–98.

- McDougall 2009, pp. 548–49.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 302–05.

- Werth 2009, p. 20.

- McDougall 2009, p. 550.

- Werth 2009, p. 19.

- Werth 2009, pp. 60–61.

- Werth 2009, p. 173.

- McDougall 2009, p. 551.

- Werth 2009, pp. 80–82.

- Werth 2009, pp. 115–121.

- Werth 2009, pp. 115–21.

- McDougall 2009, p. 552.

- Werth 2009, pp. 173–74.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 451–53.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 462–64.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 465–68.

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 3145-3146). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- Applegate 2006, p. 470.

- "6.70 MB: The Milwaukee Journal - Google News Archive Search". Https. June 22, 1962. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Applegate 2006, pp. 270–271.

- Applegate 2006, p. 353.

- McDougall 2009, p. 549.

- Applegate 2006, p. 377.

General sources

- Applegate, Debby (2006). The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher. Doubleday Religious Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-42400-6.

- Beatty, Jack (2008). Age of Betrayal: The Triumph of Money in America, 1865-1900. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4000-3242-6. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- Benfey, Christopher (2008). A Summer of Hummingbirds: Love, Art, and Scandal in the Intersecting Worlds of Emily Dickinson, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Martin Johnson Heade. Penguin Group US. ISBN 978-1-4406-2953-2.

- Goldsmith, Barbara (1999). Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-095332-4.

- Gyory, Andrew (1998). Closing the gate: race, politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-6675-7. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- Hibben, Paxton. Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait. New York: The press of the Readers club, 1942. (Foreword by Sinclair Lewis.)

- McDougall, Walter A. (2009). Throes of Democracy. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-186236-6. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- Morita, Michiyo (2004). Horace Bushnell On Women In Nineteenth-Century America. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-2888-4. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- Werth, Barry (2009). Banquet at Delmonico's: great minds, the Gilded Age, and the triumph of evolution in America. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6778-7. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

External links

- Works by Henry Ward Beecher at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Ward Beecher at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Ward Beecher at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Henry Ward Beecher by Lymon Abbott (1904)

- Henry Ward Beecher at Find a Grave

- The Beecher-Tilton Affair from the Museum of the City of New York Collections blog

- Beecher family collection from Princeton University Library. Special Collections