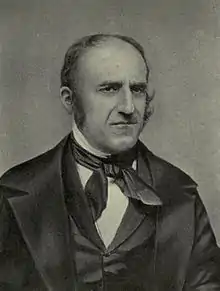

Mark Hopkins (educator)

Mark Hopkins (February 4, 1802 – June 17, 1887) was an American educator and Congregationalist theologian, president of Williams College from 1836 to 1872. An epigram — widely attributed to President James A. Garfield, a student of Hopkins — defined an ideal college as "Mark Hopkins on one end of a log and a student on the other".[1]

Life and career

Great-nephew of the theologian Samuel Hopkins, Mark Hopkins was born in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He graduated in 1824 from Williams College, where he was a tutor in 1825–1827, and where in 1830, after having graduated in the previous year from the Berkshire Medical College at Pittsfield, he became professor of Moral Philosophy and Rhetoric. In 1833 he was licensed to preach in Congregational churches. He was president of Williams College from 1836 until 1872. He was one of the ablest and most successful of the old type of college president.[2] He married Mary Hubbell in 1832 and together they parented ten children.

His volume of lectures on Evidences of Christianity (1846)[2] was delivered as a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute in January 1844. The book became a favorite textbook[2] in American Christian apologetics being reprinted in many editions up until 1909. Although not trained as a lawyer Hopkins held a lifelong interest in the law and aspects of his argument in Evidences of Christianity reflects legal metaphors and language about the veracity of eyewitness testimony to the events in the life of Jesus Christ. Much of his apologetic arguments though were a restatement of views that had been previously presented by earlier apologists such as William Paley and Thomas Hartwell Horne.

Of his other writings, the chief were Lectures on Moral Science (1862), The Law of Love and Love as a Law (1869), An Outline Study of Man (1873), The Scriptural Idea of Man (1883), and Teachings and Counsels (1884). Dr Hopkins took a lifelong interest in Christian missions, and from 1857 until his death was president of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions[2] (the foreign missions board for American Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and other Reformed Protestant churches.). He died at Williamstown, on 17 June 1887.

Reputation

President James Garfield had attended Williams College in the 1850s. At an 1871 dinner of Williams alumni, Garfield paid tribute to Hopkins, defining an ideal college as Hopkins and a student together in a log cabin. The epigram became more widely known in the pithier form retold by John James Ingalls, in which a log was substituted for the log cabin.[3] In the later judgment of university historian Frederick Rudolph, "no one can properly address himself to the question of higher education in the United States without paying homage in some way to the aphorism of the log and to Mark Hopkins".[4] In his 1903 essay "The Talented Tenth," W. E. B. Du Bois opined, "There was a time when the American people believed pretty devoutly that a log of wood with a boy at one end and Mark Hopkins at the other, represented the highest ideal of human training. But in these eager days it would seem that we have changed all that and think it necessary to add a couple of saw-mills and a hammer to this outfit, and, at a pinch, to dispense with the services of Mark Hopkins." In 1915 Hopkins was elected into the American Hall of Fame.[5]

Family

His son, Henry Hopkins (1837–1908), was also a president of Williams College. Mark Hopkins's brother, Albert Hopkins (1807–1872), was long associated with him at Williams College, where he graduated in 1826 and was successively a tutor (1827–1829), professor of mathematics and natural philosophy (1829–1838), professor of natural philosophy and astronomy (1838–1868) and professor of astronomy (1868–1872). In 1835 he organized and conducted a natural history expedition to Joggins, Nova Scotia, said to have been the first expedition of the kind sent out from any American college, and in 1837, at his suggestion and under his direction, an astronomical observatory was built at Williams College, said to have been the first in the United States built at a college exclusively for the purposes of instruction.[2]

Works

An address, delivered in South Hadley, Mass., July 30, 1840, at the third anniversary of the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, Northampton: Printed by J. Metcalf, 1840.

- Lectures on the evidence of Christianity before the Lowell Institute, January 1844, Boston: Published by T.R. Marvin, 1846.

- Revised ed. published as Evidence of Christianity. Lectures before the Lowell Institute, revised as a textbook, with a supplementary chapter considering some attacks on the critical school, the corroborative evidence of recently discovered manuscripts, etc., and the testimony of Jesus on his trial, Boston: T.R. Marvin & Son, 1887.

- Miscellaneous essays and discourses, Boston: T.R. Marvin, 1847

- A discourse commemorative of Amos Lawrence: delivered by request of the students, in the chapel of Williams College, February 21, 1853, Boston: Press of T.R. Marvin, 1853.

- Lectures on moral science, Boston: Gould and Lincoln; New York: Sheldon & Co., 1862.

- The law of love, and love as a law, or, Moral science, theoretical and practical, New York: C. Scribner, 1869.

- From 1870 published as The law of love and love as a law; or, Christian ethics.

- An outline study of man, or, The body and mind in one system with illustrative diagrams, and a method for blackboard teaching, New York: Charles Scribner, 1873

- Strength and beauty : discussions for young men, New York: Dodd & Mead, 1874.

- The Scriptural idea of man; six lectures given before the theological students at Princeton on the L.P. Stone Foundation, New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1883.

- Teachings and counsels, twenty baccalaureate sermons; with a discourse on President Garfield, New York: C. Scribr's sons, 1884.

References

- American Authors 1600–1900, p. 384.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hopkins, Mark". Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 684–685.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hopkins, Mark". Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 684–685. - Allan Peskin (1978). Garfield: A Biography. Kent State University Press. pp. 619–620. ISBN 978-0-87338-210-6.

- Frederick Rudolph (1956). Mark Hopkins and the log: Williams College, 1836–1872. Yale University Press. pp. vi, 225–8.

- Gregor Melikov (1942). The immortals of America in the Hall of Fame: men and women whose thoughts and deeds will remain the beacons of the nation through the ages. p. 86.

- "Mark Hopkins," in American Authors 1600 – 1900: A Biographical Dictionary of American Literature, edited by Stanley J. Kunitz and Howard Haycraft, (New York: H. W. Wilson Company, 1964), pp. 383–384.

- Entry on Hopkins in Philip Johnson, "Juridical Apologists 1600 - 2000 AD: A Bio-Bibliographical Essay", Global Journal of Classical Theology, Vol. 3, no. 1 (March 2002).

- John Wright Buckham, "The New England Theologians," The American Journal of Theology, vol. 24, no. 1 (January 1920), pp. 19–29.

- C. H. Lippy, "Mark Hopkins," in Dictionary of Christianity in America, edited by Daniel G. Reid, Robert D. Linder, Bruce L. Shelley & Harry S. Stout, (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press,1990), p. 553. ISBN 0-8308-1776-X

Topics

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mark Hopkins (educator) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mark Hopkins. |

- Works by Mark Hopkins at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mark Hopkins at Internet Archive

- Lectures on the Evidences of Christianity - Making of America books, University of Michigan

- Significant American Professors of Philosophy, natural Philosophy and Theology from 1637 to 1920