History of Chinese immigration to the United Kingdom

Chinese immigrants to the United Kingdom currently has more than 400,000, around 0.7% of the United Kingdom population. The first Chinese to visit Britain was Michael Alphonsius Shen Fu-tsung in 1687, who travelled to Europe with a Belgian Jesuit Father Philippe Couplet. Shen helped to translate Chinese works at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. He and Couplet left in 1688.[1]

18th Century

The first Chinese to immigrate to Britain, settling in Scotland, was William Macao who lived in Edinburgh from 1779. He was the first Chinese to marry a British woman and have children. He worked for The Board of Excise in Scotland for over 40 years. He was involved in a significant court case in 1818 related to naturalization and for a period gained Scottish nationality. He is buried in St Cuthbert's Graveyard in Edinburgh.[2]

1800s to World War II[2]

In the early 19th century, Chinese seamen began to establish small communities in the port cities of Liverpool and London. In London, the Limehouse area became the site of the first European Chinatown. The East India Company, which imported popular Chinese commodities such as tea, ceramics and silks, also brought Asian sailors and needed trustworthy intermediaries to arrange their care and lodgings while they were in London.[3] A Chinese seaman known as John Anthony took on the lucrative role of looking after Chinese sailors for the East India Company in the late 18th and early 19th century. Anthony married his British partner's daughter. Wishing to buy property, but unable to so while an alien, in 1805 he used part of the fortune he had amassed to pay for an Act of Parliament[4] naturalising him as a British subject; thus being the first Chinese to gain British citizenship. However, he died a few months after the Act was passed.

In 1839, John Hochee became the first Chinese to be naturalised by Denization and inherited the property of John Elphinstone for whom he had worked. The first Chinese student to study and graduate in Britain was Huang Kuan who attended Edinburgh University Medical School from 1850 to 1855, but like other Chinese who studied in Britain returned to live in China.

Before 1900, only a few Chinese who came to Britain as seamen, servants, jugglers, etc. decided to stay, and some married British women. By the mid-1880s, small Chinatowns started to form in London and Liverpool with grocery stores, eating houses and meeting places and, in the East End, Chinese street names. By 1890, there were two distinct, if small, Chinese communities living in east London. Chinese from Shanghai settled around Pennyfields, Amoy Place, and Ming Street and those from Guangzhou Canton and Northern and Southern China lived around Gill Street and Limehouse Causeway. Liverpool also saw the beginning of a Chinese community, although this remained small until later in the 20th century.

In 1877, Kuo Sung-tao, the first Chinese minister to Britain, opened the country's legation in London.

There was growing prejudice against the Chinese community, particularly among British seamen who misperceived the Chinese seamen as a threat to their jobs. This prejudice was fed by media misrepresentations of the Chinese in Limehouse and Liverpool as being heavily involved in gambling and opium use, and objections to Chinese marrying British women.

From the early 1900s, due to being blocked from any other employment, many Chinese established small laundries. As few Chinese women lived in Britain, a number married British women and the laundries were operated as family concerns with all the family assisting. A few opened restaurants in their communities and the first recorded Chinese restaurant opened in London's Soho area in 1907. A small number of others also opened there, although it was not until the 1970s that London Soho Chinatown began to grow.

There was resistance to Chinese settling in Britain. After World War I ended, the Aliens Restriction Act was extended in 1919 to include peacetime, bringing about a decline in the Chinese population in Britain. In spite of requests from some of the 100,000 Chinese brought from China to serve in the Chinese Labour Corp in France and Belgium during the war to live in Britain, not one was given permission to enter the country. By 1918, the number of Chinese living in Pennyfields, Poplar totalled less that 200; all were men and nine of them had English wives. Although the numbers of Chinese residing in Limehouse, Liverpool and other ports fluctuated, the number of settled Chinese immigrants before the 1950s remained relatively small.

In World War II as more men were required to crew British merchant ships, the Chinese Merchant Seamen's Pool of approximately 20,000 was established with its headquarters in Liverpool. However, at the end of the war few Chinese who had worked as merchant seamen were allowed to remain in Britain. The British Government and the shipping companies colluded to forcibly repatriate thousands of Chinese seamen.[5] Many of the seamen left behind wives and mixed-race children that they would never see again.[5] More than 50 years later in 2006, a memorial plaque in remembrance for those Chinese seamen was erected on Liverpool's Pier Head.[6][7]

Post-World War II

The 1951 Census recorded a big increase in Britain's Chinese population, then standing at 12,523, of whom over 4,000 were from Malaysia, and 3,459 single males from Hong Kong. The influx of Chinese into Britain coincided with the increased pressure in Hong Kong due to the build-up of the huge numbers of refugees streaming in from China following the end of the Chinese Civil War. At the time, nearly 100 Chinese restaurants were open, as former embassy staff and ex-seamen found a niche in this trade. Records showed remittances to Hong Kong of HK$ 2.5 million.

The largest wave of Chinese immigration took place during the 1950s and 1960s and consisted predominantly of male agricultural labourers from Hong Kong, particularly from the rural villages of the New Territories. This also included immigration, through Hong Kong, from the Guangdong province of China. The majority of these Chinese men were employed in the then growing Chinese catering industry. By 2004 for comparison, according to official figures, just under half of Chinese men and 40% of Chinese women in employment worked in the distribution, hotel, and restaurant industry.[8]

Since the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, restrictions were placed on immigration from current and former British colonies, and these were tightened by successive governments. The Immigration act included a voucher system and significant Chinese migration to Britain did still continue by relatives of already settled Chinese and by those qualified for skilled jobs, until the end of the 1970s. Today, a significant proportion of British Chinese are second or third generation descendants of these post-World War II immigrants. Approximately 30,000 workers from the New Territories were resident in Britain in 1962 and records showed remittances at HK$40 million. Ninety-six wives from Hong Kong joined their husbands in Britain in the beginning of that year, indicating a new phase from 'sojourning' to family reunion and a more settled life.

In 1976, Britain's Chinese population included approximately 6,000 full-time students and 2,000 nurses. The 1981 British Nationality Act deprived Hong Kong British Overseas Territories citizens of the right of abode in the United Kingdom, an issue that caused some controversy in the years leading up to the territory's handover to China in 1997. After the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, it was considered necessary to devise a British Nationality Selection Scheme to enable some of the population to obtain British citizenship to maintain confidence in Hong Kong and to counteract the effects of the emigration of many of its most talented residents. The United Kingdom made a provision to grant citizenship to 50,000 families, whose presence was important to the future of Hong Kong, under the British Nationality Act (Hong Kong) 1990. (See also British nationality law and British nationality law and Hong Kong).

In 1981, the Census recorded Britain's Chinese population as 154,363. Thirty-five Chinese-language newspapers and 362 periodicals were on sale from seven bookshops in Soho. Sing Tao itself had a circulation of 10,000 in Britain. The Chinese population now numbered the elderly, and 30,000 children in British schools. Of these, 75 percent were born in the country, representing a new phase of settlement. In 1982, the Merseyside Chinese Community Services opened the 'Pagoda of Hundred Harmony', an advice centre built with the help of an Urban Aid grant. In 1983, the Chinese Information and Advice Centre (CIAC), an amalgamation of the Chinese Workers Group (1975) and the Chinese Action Group (1980) received Greater London Council (GLC) funding for a centre. Sixty Chinese associations, including women's groups and old people's clubs, were consolidated into two national umbrella organisations. There were approximately 7,000 restaurants, takeaways and other Chinese owned businesses, indicating a slow-down in the rate of growth. There were 926 students attending the Chinese Chamber of Commerce Mother Tongue School, which ran classes up to O-level standard.

The most significant migration from China commenced in mid-1980s. This coincided with the Chinese government's relaxed restrictions on emigration, although most left for the United States, Canada, and Australia. In 1984–85, the British and Chinese governments signed the Draft Agreement on the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong to China in 1997. Construction was also begun of Manchester's Chinatown archway (now the largest in Europe), and was completed in 1987. The House of Commons Home Affairs Committee report identified five main problems faced by the Chinese in Britain. Recommendations included more language training, careers advice, community centres, and interpretation and advice services. Over 50 percent of the Chinese population was under 30; 50 percent lived outside the large metropolitan areas; only 2 percent were professionals, which included doctors, solicitors, architects, bankers, stockbrokers, business executives, teachers and university lecturers.

In 1987, Manchester's Chinatown Archway, the largest in Europe, was completed, marking co-operation between the government of China, Manchester City Council and the local Chinese community. Currently, the largest Chinese arch in the UK is located in Chinatown, Liverpool. It was constructed in 2000 and is also the largest such archway in the world outside of China.[9]

As Hong Kong and China became wealthier during the 1990s, Hong Kong and Chinese parents increasingly sent their children to study in the UK and elsewhere. An estimated 80,000 Hong Kong and Chinese students attended UK universities in the academic year of 2004–05. Small numbers of unskilled migrants from China sought employment in the UK in the early 1990s. In recent years, there has been an increase in illegal immigrants coming from China and other countries into the United Kingdom, some of whom pay traffickers (so-called "snakeheads") to smuggle them into many Western countries. Due to historical and cultural reasons, a sizeable proportion originate from Fujian province in southeast China. Others are citizens from the Commonwealth countries (mostly former British colonies), who have been able to obtain tourist or student visas and remain in the UK after their visas have expired. Most work in the black economy or are employed as illegal cheap labour, usually in agriculture and catering. This activity became publicised nationwide in tragic consequences in the form of the 2004 Morecambe Bay cockling disaster, though most migrants have remained invisible.

In April 2001, one of the largest demonstrations by the Chinese community, with around 1,000 people protesting, was held in London against media reports that Chinese restaurants had started the 2001 United Kingdom foot-and-mouth crisis by using diseased meat. Within weeks, a Chinese community monitoring group reported that trade at restaurants and takeaways had plummeted because an unsubstantiated rumour had become a scare story labelling an entire community as "dirty". Following the march, the then Agriculture Secretary Nick Brown publicly denied that the rumours had begun in his department and described the controversy as a racist attack on the Chinese community.[10] As of 2001, there were about 12,000 Chinese takeaways and 3,000 Chinese restaurants in the UK.[11]

Communities

From the beginning of Chinese settlement in the ports of London and Liverpool, there were no Chinatowns but communities of mixed families. Because few Chinese women were able to come to Britain, Chinese seamen established homes with local women. Many did not actually marry because that meant the woman could lose her British citizenship and would become an alien, resulting in restrictions on travel and benefits. The children of such unions often faced discrimination when it came to finding jobs. Many followed the example of Yorkshire-born Harry Cheong who had an exemplary army record during the Second World War, including fighting in Burma for which he was mentioned in dispatches. But on leaving the army he had to change his surname to get a job interview and has since lived as Harry Dewar. Such name changes have meant much Chinese history in Britain is now difficult to trace. Notable people who had Chinese fathers and English mothers include footballer Hong Y "Frank" Soo, who played for Stoke City (1933–1945) and Leslie Charteris who wrote The Saint novels that were made into the successful 1960s TV series.[12]

Liverpool

The first presence of Chinese people in Liverpool dates back to the early 19th century, with the main influx arriving at the end of the 18th century. This was in part due to the Alfred Holt and Company establishing the first commercial shipping line to focus on the China trade. From the 1890s onwards, small numbers of Chinese began to set up businesses catering to the Chinese sailors working on Holt's lines and others. Some of these men married working class British women, resulting in a number of British-born Eurasian Chinese being born during World War II in Liverpool. At the beginning of the War, there were up to 20,000 Chinese mariners in the city. In 1942, there was a strike for rights and pay equal to that of white mariners. The strike had lasted for 4 months. For the duration of the War these men were labelled as "troublemakers" by the shipowners and the British Government. At the end of the conflict, they were forbidden shore jobs, their pay was cut by two-thirds and they were offered only one-way voyages back to China. Hundreds of men were forced to leave their families, with many of their Eurasian children continuing to live in and around Liverpool's Chinatown to this day.[13]

London

Britain began trading with China in the 17th century and a small community of Chinese sailors grew up around Limehouse over the next two centuries. Due to heavy bomb damage, however, the number of Chinese in the area rapidly decreased. Changes to labour laws during the early 20th century meant that Chinese sailors found it increasingly difficult to find employment on ships. They turned instead to running to laundries and restaurants. From the 1960s on, the number of Chinese immigrating to London grew significantly with the main influx being from the New Territories (the mainland area of Hong Kong) coming to Britain to work in Chinese restaurants and take-aways. In London, Chinese restaurants expanded, especially in the Soho and Bayswater areas. Most who came spoke Cantonese or Hakka, though written Chinese was a means of communication for the whole community. The Chinese established various organisations such as language schools, gambling houses for socialising, and a Chinese Church in the West End. One notorious club was the Chi Kung Tong (Achieve Justice Society), the first Triad Society in Britain.[14]

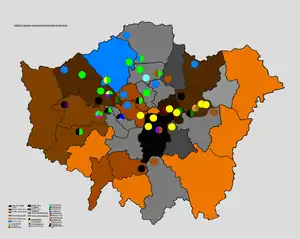

By the late 1960s, the Chinese restaurants and shops around Gerrard Street, Lisle Street, and Little Newport Street had evolved into "Tong Yan Kai", otherwise known as Chinatown. The general public developed a taste for Chinese food during the postwar restaurant boom. In 1963, the Zhongshan Workers' Club opened in the West End, showing films and running classes. The first Chinese New Year celebrations were held in Gerrard Street. The Overseas Chinese Service opened the first specialised agency to assist the Chinese in dealing with the host society by offering a translation and interpreting service. In the 1970s and 1980s, many ethnic Chinese who had settled in Vietnam for generations were forced to leave as "boat people" following the Vietnam War. Many settled in Lewisham, Lambeth, and Hackney, as well as elsewhere in the UK. The 1980s and 1990s saw a migration of academics and professionals from Chinatown to the suburbs of Croydon and Colindale. Since the 1980s, London's Chinatown has been transformed by Westminster City Council to become a major tourist attraction and a cultural focal point of the Chinese community in London. Today over 100,000 Chinese people live in London, and are more evenly dispersed throughout the city and its boroughs. Roughly a quarter of the Chinese population of the United Kingdom now live in London, mainly in the boroughs of Barnet, Haringey, Waltham Forest, Hackney, Southwark and Westminster. Mare Street in Hackney is the hub of a small Vietnamese community. The principal languages of the London Chinese community are Cantonese and Hakka (from the New Territories, Hong Kong, and Vietnam). There are also some speakers of Hokkien, Teochew and Hainanese. The Chinese from the People's Republic of China, Taiwan, and Singapore tend to speak Mandarin (or Putonghua). A large network of Chinese schools and community centres offers support and a means of passing on cultural identity from one generation to the next.

Sheffield

Sheffield has no official Chinatown although London Road, Highfield is the centre of the Sheffield Chinese community. There are many Chinese restaurants, supermarkets, and community stores as well as the Sheffield Chinese Community Centre. The Sheffield Chinese community is pressing for the street to be formally labelled Sheffield's Chinatown. The Chinese community in Sheffield is also spreading toward the city centre, with a notable number of Chinese people, greatly influenced by the city's university, which has the largest number of Chinese in the country.

Wales

The largest two communities of Chinese people in Wales are in Swansea (approx 2,000+),[16] and Cardiff (approx 1,750+), both of which were major port towns. A number of the former seamen from the port of Liverpool have retired, with a resultant aged community in Gwynedd.[17] There are noted Chinatowns in both cities, as well as dedicated Chinese cemeteries.[18]

References

- Price, Barclay (2019). The Chinese in Britain - A History of Visitors and Settlers. UK: Amberley Books. ISBN 9781445686646.

- Gomez, Benton, Edmund Gregor (2008). The Chinese in Britain, 1800 - present, Economy, Transnationalism, Identity. UK: Palgrave Macmilan. ISBN 978-0-230-28850-8.

- A South Asian History of Britain: Four Centuries of Peoples from the Indian Subcontinent, Michael Fisher, Shompa Lahiri and Shinder Thandi. London: Greenwood Press, May 2007.

- The Gentleman’s Magazine, August 1805 - obituary of John Anthony

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-33962179

- Yvonne Foley has set up Half and Half, a network for families of Chinese seamen who were repatriated after the Second World War.

- Chinese Liverpudlians: A history of the Chinese Community in Liverpool, by Maria Lin Wong. Liver Press, 1989.

- "National Statistics 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-07-22. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- http://www.visitliverpool.com/site/chinese-arch-p54681

- Chinese Britain BBC News Online

- Chinese restaurant 'not disease source'

- BBC - Radio 4 - Chinese in Britain

- Liverpool and its Chinese Seaman

- Robertson, Frank. Triangle of Death. The Inside Story of the Triads - the Chinese Mafia. Routledge 1977. p. 14.

- January 2005 survey and maps of ethnic and religious diversity in London Guardian Online

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/south_west/3654578.stm

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/north_west/5052176.stm

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/south_east/8602713.stm