History of yellow fever

The evolutionary origins of yellow fever most likely came from Africa. [1][2] Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the virus originated from East or Central Africa, with transmission between primates and humans, and spread from there to West Africa.[3] The virus as well as the vector Aedes aegypti, a mosquito species, were probably brought to the western hemisphere and the Americas by slave trade ships from Africa after the first European exploration in 1492.[4]

The first outbreaks of disease that were probably yellow fever occurred in the Windward Islands of the Caribbean, on Barbados in 1647 and Guadeloupe in 1648.[5] Barbados had undergone an ecological transformation with the introduction of sugar cultivation by the Dutch. Plentiful forests present in the 1640s were completely gone by the 1660s. By the early 18th century, the same transformation related to sugar cultivation had occurred on the larger islands of Jamaica, Hispaniola and Cuba. Spanish colonists recorded an outbreak in 1648 on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico that may have been yellow fever. The illness was called xekik (black vomit) by the Maya.

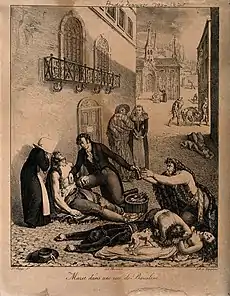

At least 25 major outbreaks followed in North America, such as in 1793 in Philadelphia, where several thousand people died, more than nine percent of the total population. The American government, including George Washington, had to flee the city, which was the capital of the United States at the time. In 1878, about 20,000 people died in an epidemic which struck the towns of the Mississippi River Valley and its tributaries. The last major outbreak in the US occurred in 1905 in New Orleans. Major outbreaks also occurred in Europe in the 19th century in Atlantic ports following the arrival of sailing vessels from the Caribbean, most often from Havana.[6] Outbreaks occurred in Barcelona, Spain, in 1803, 1821, and 1870. In the last outbreak, 1,235 fatalities were recorded of an estimated 12,000 cases.[7] Smaller outbreaks occurred in Saint-Nazaire in France, Swansea in Wales, and in other European port cities, following the arrival of vessels carrying the mosquito vector.[8][9]

The first mention of the disease by the name "yellow fever" occurred in 1744.[10] Many famous people, mostly during the 18th through the 20th centuries, contracted and then recovered from, or died of, yellow fever.

Philadelphia 1793-1805

The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793 struck during the summer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where the highest fatalities in the United States were recorded. The disease probably was brought by refugees and mosquitoes on ships from Saint-Domingue. It rapidly spread in the port city, in the crowded blocks along the Delaware River. About 5000 people died, ten percent of the population of 50,000. The city was then the national capital, and the national government left the city, including President George Washington. Philadelphia, Baltimore and New York suffered repeated epidemics in the 18th and 19th centuries, as did other cities along the East and Gulf coasts.[11]

At the time, the known solution to recovery was found to be long and tedious as it was expected that patients needed to consume bitters and country air away from the metropolitan area, in order to recover.[12] Yet the average citizen typically sought medical help from the Pennsylvania Hospital.[12] Year after year starting in 1793, yellow fever returned to major cities along the east coast including Philadelphia leaving investigators stagnant in regard to progress made in the search for the cause of yellow fever.[13] Yellow Fever's prevalence during this era killed over 10,000 people starting in 1793 where nearly 5,000 people died, striking again in 1797 tallying about 1,500 people, and again the next year in 1798 killing 3,645 people.[13]

Potential Causes

With the spread of yellow fever in 1793, physicians of the time used the increase number of patients to increase the knowledge in disease as the spread of yellow fever, helping differentiate between other prevalent diseases during the time period as cholera, and typhus were current epidemics of the time as well.[12] As doctors and people of interest investigated the cause of yellow fever, two main hypotheses derived from the confusing data they collected.[13] The first being the disease is contagious, as the disease is spread through the contact of people, as ships from the already infected Caribbean Islands had spread to major cities.[13] The second hypothesis being that the disease derived from local sources proposing that contact with them caused the sickness rather than the spreading be with people as yellow fever seemed to be prevalent in major cities and less effective in rural areas.[13]

Haiti: 1790–1802

The majority of the British soldiers sent to Haiti in the 1790s died of disease, chiefly yellow fever.[14][15] There has been considerable debate over whether the number of deaths caused by disease was exaggerated.[16]

In 1802–1803, an army of forty thousand sent by First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte of France to Saint Domingue to suppress the Haitian Revolution mounted by slaves, was decimated by an epidemic of yellow fever (among the casualties was the expedition's commander and Bonaparte's brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc). Some historians believe Napoleon intended to use the island as a staging point for an invasion of the United States through Louisiana (then newly regained by the French from the Spanish.).[17][15] Others believe that he was most intent on regaining control of the lucrative sugar production and trade in Saint-Domingue. Only one-third of the French troops survived to return to France, and in 1804 the new republic of Haiti declared its independence.

Savannah, Georgia: 1820

Nearly 700 people in Savannah, Georgia, died from yellow fever in 1820, including two local physicians who lost their lives caring for the stricken.[18] An outbreak on an immigrant ship with Irish natives in 1819 led to a passage of an act to prevent the arrival of immigrant ships, which did not prevent the epidemic where 23% of the deaths were of Irish descent.[19] Several other epidemics followed, including 1854[20] and 1876.[21]

New Orleans, Louisiana: 1853

The 1853 outbreak claimed 7,849 residents of New Orleans. The press and the medical profession did not alert citizens of the outbreak until the middle of July, after more than one thousand people had already died. The New Orleans business community feared that word of an epidemic would cause a quarantine to be placed on the city, and their trade would suffer. In such epidemics, steamboats frequently carried passengers and the disease upriver from New Orleans to other cities along the Mississippi River.

The epidemic was dramatized and featured in the plot of the 1938 film Jezebel, starring Bette Davis.

Yellow fever was a threat in New Orleans and south Louisiana virtually every year, during the warmest months. Among the more prominent victims were: Spanish colonial Governor Manuel Gayoso de Lemos (1799); the first and second wives (d. 1804 and 1809) of territorial Governor William C. C. Claiborne and his young daughter (1804); one of New Orleans' most important early city planners Barthelemy Lafon (1820), architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe and one of his sons (1820, 1817, respectively), who were in New Orleans building the city's first waterworks; Jesse Burton Harrison (1841), a young lawyer and author;[22] Confederate Brig. Gen. Young Marshall Moody (1866); architect James Gallier, Jr. (1868); and Confederate Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood and his wife and daughter (1879).[23]

Norfolk, Virginia: 1855

A ship carrying persons infected with the virus arrived in Hampton Roads in southeastern Virginia in June 1855.[25] The disease spread quickly through the community, eventually killing over 3,000 people, mostly residents of Norfolk and Portsmouth. The Howard Association, a benevolent organization, was formed to help coordinate assistance in the form of funds, supplies, and medical professionals and volunteers, who poured in from many other areas, particularly the Atlantic and Gulf Coast areas of the United States.[26]

Bermuda: 1843, 1853. 1856, 1864

Bermuda suffered four yellow fever epidemics in the 1800s, both mosquito borne and via visiting ships, and in total claimed the lives of 13,356 people, including Military and civilian population. During the 1864 epidemic, a Dr. Luke Pryor Blackburn, from Halifax, Nova Scotia, visited the island several times, to assist the local medical community on account of his knowledge of the disease, and when he left in October 1864, he left behind some trunks of soiled clothing that were to have been sent to him in Canada. Fortunately the trunks were located and the contents destroyed.

It became evident that Dr Blackburn's visits had been financed by the Confederacy, and that a certain Union informer had been offered $60,000 to distribute Dr. Blackburn's trunks of soiled clothing to Union cities including Boston, Philadelphia, Washington and Norfolk. Also one trunk went to New Bern, which was identified as having brought yellow fever to that city, claiming the lives of 2,000 people.

Blackburn was arrested and tried, but acquitted owing to lack of evidence, other than hearsay by witnesses, meaning that the culprit trunks could not be located, and in 1878, he went on heroically, to fight yellow fever in Kentucky where he had set up practice in Louisville, and was eventually elected governor of that state.

Texas and Louisiana: 1867

The 1867 yellow fever epidemic claimed many casualties in the southern counties of Texas, as well as in New Orleans. The deaths in Texas included Union Maj. Gen. Charles Griffin, Margaret Lea Houston (Mrs. Sam Houston), and at least two young physicians and their family members.[27]

Lower Mississippi Valley: 1878

Events Leading Up to the Epidemic

During the American Civil War, New Orleans was occupied with Union troops, and the local populace believed that yellow fever would only kill the northern troops.[28] These rumors instilled fear into the Union troops, and they actively practiced sanitation and quarantine procedures during their occupation in 1862 until the government pulled federal troops out of the city in 1877.[29] The withdrawal of Union troops resulted in the relaxation of sanitation and quarantine efforts in New Orleans.[29] Following the yellow fever epidemic in Shreveport, Louisiana, where 769 people died between August and November, the states in the Lower Mississippi Valley began to take precautions for any following epidemics.[30] After the epidemic in Shreveport, the Quarantine Act of 1878 was passed that allowed the United States federal government to assume control over the state in quarantines, but the law did not allow for the federal government to intercede on local medical authorities or health boards.[31] In March of that year, a virulent strain of Yellow Fever was found in Havana, Cuba, and New Orleans health officials ordered the detainment of all vessels from the Cuban and Brazilian regions.[31] It is unknown what exactly led to the outbreak in the Mississippi River Valley as causes range from unchecked vessels from the fruit trade to refugees from the Ten Years' War in Cuba, which was experiencing a rise in yellow fever cases, however, investigations at the time suggest that the epidemic originated from the steamer Emily B. Souder on May 22, 1878.[32]

Effects of the Epidemic on the Region

The entire Mississippi River Valley from St. Louis south was affected, and tens of thousands fled the stricken cities of New Orleans, Vicksburg, and Memphis. The epidemic in the Lower Mississippi Valley also greatly affected trade in the region, with orders of steamboats to be tied up in order to reduce the amount of travel along the Mississippi River, railroad lines were halted, and all the workers to be laid off.[33] Carrigan states that "An estimated 15,000 heads of households were unemployed in New Orleans, 8,000 in Memphis, and several thousands more in scattered small towns - representing a total of over 100,000 persons in dire need."[33]

New Orleans

When the epidemic broke out from the Emily B. Souder in May, roughly 40,000 residents that represent 20% of the city population fled the city, many of whom fled via the new railroads systems constructed during the Reconstruction period after the American Civil War, which further spread the virus across the Lower Mississippi Valley.[34] The city saw roughly 20,000 total infections during the epidemic with 5,000 resulting in deaths, and saw a loss of more than $15 million due to the disruptions in trade from the epidemic.[34]

Due to the struggles of the remaining citizens, numerous organizations formed relief committees that relied heavily on aid from the federal government in the form of relief rations and money donations from unaffected cities in the Northern United States.[35] The federal relief came with heavy restrictions, as they were only allowed to be given to households that had yellow fever and could provide proof via a doctor's certificate or given to people considered "destitute."[35] These restrictions led to many citizens having to go without federal aid, resulting in roughly 10,000 people receiving aid despite there being 20,000 cases of yellow fever alone.[36]

Memphis

Memphis suffered several epidemics during the 1870s, culminating in the 1878 epidemic (called the Saffron Scourge of 1878), with more than 5,000 fatalities in the city. Some contemporary accounts said that commercial interests had prevented the rapid reporting of the outbreak of the epidemic, increasing the total number of deaths. People still did not understand how the disease developed or was transmitted, and did not know how to prevent it.[37]

The news of deaths in New Orleans and in the nearby town of Hickman in August led to the mass withdrawal of an estimated 25,000 residents from the city of Memphis within four days, which led to further the spread of the virus across the Lower Mississippi Valley.[38] Memphis also saw an economic crisis during the epidemic, where trade was halted entirely in the city, and the lack of commerce led to mass starvations throughout the city, inciting riots and looting.[39] All in all, Ellis states that " of the approximately 20,000 persons remaining in the city, an estimated 17,000 contracted the fever, of whom 5,150 died. There were at least 11,000 cases among 14,000 blacks, resulting in 946 deaths. By contrast, virtually all of the 6,000 whites were stricken, and 4,204 cases proved fatal. The disaster's economic cost to the city was later calculated to be upward of fifteen million dollars."[40]

Mississippi

The 1878 epidemic was the worst that occurred in the state of Mississippi. Sometimes known as "Yellow Jack", and "Bronze John", devastated Mississippi socially and economically. Entire families were killed, while others fled their homes for the presumed safety of other parts of the state. Quarantine regulations, passed to prevent the spread of the disease, brought trade to a stop. Some local economies never recovered. Beechland, near Vicksburg, became a ghost town because of the epidemic. By the end of the year, 3,227 people had died from the disease.[41]

In the town of Grenada located in northern Mississippi, about 1,000 people of the town's population fled while the remaining population suffered "approximately 1,050 cases and 350 deaths."[42] The town was a known railroad town, and it was found that the refugees from railroad towns often spread then illness with them along the railroads.[43]

Aftermath

The epidemic lasted until late October when lower temperatures drove off the A. Aegypti mosquitoes, the primary carrier of yellow fever, away or into hibernation.[44] It was not until November 19 when the epidemic was officially declared to be over.[44] Ellis states that "according to estimates, there were around 120,000 cases of yellow fever and approximately 20,000 deaths."[44] The Lower Mississippi Valley also experienced roughly $30 million in economic losses due to the disruption of commerce caused by the epidemic.[34]

The French Panama Canal Effort: 1882–1889

The French effort to build a Panama Canal was damaged by the prevalence of endemic tropical diseases in the Isthmus. Although malaria was also a serious problem for the French canal builders, the numerous yellow fever fatalities and the fear they engendered made it difficult for the French company to retain sufficient technical staff to sustain the effort. Since the mode of transmission of the disease was unknown, the French response to the disease was limited to care of the sick. The French hospitals contained many pools of stagnant water, such as basins underneath potted plants, in which mosquitoes could breed. The numerous deaths eventually led to the failure of the French company licensed to build the canal, resulting in a massive financial crisis in France.[45]

See also

- Timeline of yellow fever

References

- Gould EA, de Lamballerie X, Zanotto PM, Holmes EC (2003). Origins, evolution, and vector/host coadaptations within the genus Flavivirus. Advances in Virus Research. 59. pp. 277–314. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(03)59008-X. ISBN 978-0-12-039859-1. PMID 14696332.

- McNeill, J. R. (2010). Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620–1914 (1st edn, p. 390). Cambridge University Press. Via Amazon.

- Bryant, J. E.; E. C. Holmes; A. D. T. Barrett (2007). "Out of Africa: A Molecular Perspective on the Introduction of Yellow Fever Virus into the Americas". PLOS Pathog. 3 (5): e75. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030075. PMC 1868956. PMID 17511518.

- Haddow (2012). "X.—The Natural History of Yellow Fever in Africa". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Section B. 70 (3): 191–227. doi:10.1017/S0080455X00001338.

- McNeill, J. R. (1 April 2004). "Yellow Jack and Geopolitics: Environment, Epidemics, and the Struggles for Empire in the American Tropics, 1650–1825". OAH Magazine of History. 18 (3): 9–13. doi:10.1093/maghis/18.3.9.

- Barrett AD, Higgs, S (2007). "Yellow fever: a disease that has yet to be conquered". Annu. Rev. Entomol. 52: 209–29. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.52.110405.091454. PMID 16913829. S2CID 9896455.

- Canela Soler, J; Pallarés Fusté, MR; Abós Herràndiz, R; Nebot Adell, C; Lawrence, RS (2008). "A mortality study of the last outbreak of yellow fever in Barcelona City (Spain) in 1870". Gaceta Sanitaria / S.E.S.P.A.S. 23 (4): 295–9. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2008.09.008. PMID 19268397.

- Coleman, W (1983). "Epidemiological method in the 1860s: yellow fever at Saint-Nazaire". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 58 (2): 145–63. PMID 6375767.

- Meers, P. D. (August 1986). "Yellow fever in Swansea, 1865". The Journal of Hygiene. 97 (1): 185–91. doi:10.1017/s0022172400064469. PMC 2082871. PMID 2874172.

- The earliest mention of "yellow fever" appears in a manuscript of 1744 by Dr. John Mitchell of Virginia; copies of the manuscript were sent to Mr. Cadwallader Colden, a physician in New York, and to Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia; the manuscript was eventually printed (in large part) in 1805 and reprinted in 1814. See:

- (John Mitchell) (1805) (Mitchell's account of the Yellow Fever in Virginia in 1741–2), The Philadelphia Medical Museum, 1 (1) : 1–20.

- (John Mitchell) (1814) "Account of the Yellow fever which prevailed in Virginia in the years 1737, 1741, and 1742, in a letter to the late Cadwallader Colden, Esq. of New York, from the late John Mitchell, M.D.F.R.S. of Virginia," American Medical and Philosophical Register, 4 : 181–215. The term "yellow fever" appears on p. 186. On p. 188, Mitchell mentions "… the distemper was what is generally called the yellow fever in America." However, on pages 191–192, he states "… I shall consider the cause of the yellowness which is so remarkable in this distemper, as to have given it the name of the Yellow Fever."

- Campbell, Ballard C. (ed.), American Disasters: 201 Calamities That Shook the Nation (2008), pp. 49–50.

- Holliday, Timothy Kent (2020-01-01). "Morbid Sensations: Intimacy, Coercion, and Epidemic Disease in Philadelphia, 1793-1854". Dissertations available from ProQuest: 1–326.

- Apel, Thomas (2012). "Feverish Bodies, Enlightened Minds: Yellow Fever and Common-Sense Natural Philosophy in the Early American Republic, 1793-1805" (thesis thesis). Georgetown University.

- Geggus, David (1982). "The British Army and the Slave Revolt". History Today. 32 (7): 35–39.

- Marr, John S., and John T. Cathey. "The 1802 Saint-Domingue yellow fever epidemic and the Louisiana Purchase." Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 19#.1 (2013): 77–82. online Archived 2016-02-04 at the Wayback Machine. Also via: Marr, J. S.; Cathey, J. T. (2013). "The 1802 Saint-Domingue yellow fever epidemic and the Louisiana Purchase". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 19 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1097/PHH.0b013e318252eea8. PMID 23169407.

- Girard, Philippe R. (2011). The Slaves Who Defeated Napoleon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801-1804. University of Alabama Press. pp. 179–80. ISBN 9780817317324.

- Bruns, Roger (2000). Almost History: Close Calls, Plan B's, and Twists of Fate in American History. Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-8579-3.

- Waring, William R. (1821). Report to the City Council of Savannah on the epidemic disease of 1820. Savannah: Henry P. Russell. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Patterson, K. David. "Yellow fever epidemics and mortality in the United States, 1693-1905". Social Science & Medicine. 34: 855–865.

- Lockley, Tim (2012). "'Like a clap of thunder in a clear sky': differential mortality during Savannah's yellow fever epidemic of 1854" (PDF). Social History. 37 (2): 166–186. doi:10.1080/03071022.2012.675657. S2CID 2571401.

- Denmark, Lisa L. (2006). "At the Midnight Hour": Economic Dilemmas and Harsh Realities in Post-Civil War Savannah". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 90 (3). Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- O'Brien, Michael (1 May 2008). All Clever Men, Who Make Their Way: Critical Discourse in the Old South. ISBN 9780820332017.

- "Died in New Orleans or La. of yellow fever". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Report of the Philadelphia Relief Committee. Philadelphia: Inquirer Printing Office. 1856. pp. 1–5. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Mauer, H. B. "Mosquito control ends fatal plague of yellow fever". etext.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved 11 June 2007. (undated newspaper clipping).

- Bluemink DonnaYellow Fever in Norfolk and Portsmouth , Virginia, 1855, as reported in the Daily Dispatch Richmond, Virginia, retrieved 14 March 2019 editor /transcriber http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/yellow-fever//yfinindex.html#generalindex

- "Died in Texas yellow fever epidemics". Findagrave.com. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Willoughby, Urmi Engineer (2017). Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-century New Orleans. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8071-6774-8.

- Willoughby, Urmi Engineer (2017). Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-century New Orelans. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8071-6774-8.

- Smith, Henry (1874). "Report of the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1873" (PDF). Louisiana Equitable Life Insurance Company.

- Ellis, John H. (1992). Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 37. ISBN 0-8131-1781-X.

- Ellis, John H. (1992). Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 39. ISBN 0-8131-1781-X.

- Carrigan, Jo Ann (1963). "Impact of Epidemic Yellow Fever on Life in Louisiana". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 4: 5–34 – via JSTOR.

- Willoughby, Urmi Engineer (2017). Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-century New Orleans. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana Statue University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8071-6774-8.

- Willoughby, Urmi Engineer (2017). Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-century New Orleans. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-8071-6774-8.

- Willoughby, Urmi Engineer (2017). Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-century New Orleans. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8071-6774-8.

- Crosby, M. C. (2006), The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic That Shaped Our History.

- Ellis, John H. (1992). Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 43. ISBN 0-8131-1781-X.

- Ellis, John H. (1992). Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 47. ISBN 0-8131-1781-X.

- Ellis, John H. (1992). Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 57. ISBN 0-8131-1781-X.

- Stephens Nuwer, Deanne (1999). "The 1878 Yellow Fever Epidemic along the Mississippi Gulf Coast". Gulf South Historical Review. 14 (2): 51–73.

- Ellis, John (1992). Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 43. ISBN 0-8131-1781-X.

- Willoughby, Urmi Engineer (2017). Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-century New Orleans. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8071-6774-8.

- Ellis, John H. (1992). Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 56. ISBN 0-8131-1781-X.

- McCullough, David (1978), The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914, New York: Simon & Schuster (a comprehensive history of the building of the canal).

External links

- "'Bronze John': Yellow fever epidemics in New Orleans" at The Times-Picayune; updated 27 September 2013, accessed 31 October 2015.

- Great Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1820 historical marker in Savannah, Georgia