Hokusai

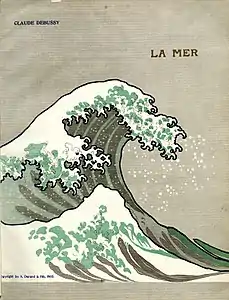

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾 北斎, c. 31 October 1760 – 10 May 1849), known simply as Hokusai, was a Japanese artist, ukiyo-e painter and printmaker of the Edo period.[1] Born in Edo (now Tokyo), Hokusai is best known as author of the woodblock print series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji which includes the internationally iconic print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

Hokusai | |

|---|---|

北斎 | |

.png.webp) Self portrait at the age of eighty-three | |

| Born | Tokitarō 時太郎 supposedly 31 October 1760 |

| Died | 10 May 1849 (aged 88) Edo (present-day Tokyo), Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Known for | Ukiyo-e painting, manga and woodblock printing |

Notable work | The Great Wave off Kanagawa |

Hokusai created the monumental Thirty-Six Views both as a response to a domestic travel boom and as part of a personal obsession with Mount Fuji.[2] It was this series, specifically The Great Wave print and Fine Wind, Clear Morning, that secured Hokusai's fame both in Japan and overseas. While Hokusai's work prior to this series is certainly important, it was not until this series that he gained broad recognition.[3]

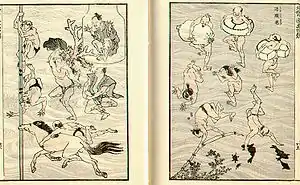

His work transformed the ukiyo-e artform from a style of portraiture largely focused on courtesans and actors into a much broader style of art that focused on landscapes, plants, and animals. Hokusai worked in various fields besides woodblock prints, such as painting and producing designs for book illustrations, including his own educational Hokusai Manga, which consists of thousands of images of every subject imaginable over fifteen volumes. Starting as a young child, he continued working and improving his style until his death, aged 88. In a long and successful career, he produced over 30,000 paintings, sketches, woodblock prints, and images for picture books in total. Innovative in his compositions and exceptional in his drawing technique, Hokusai is considered one of the greatest masters in the history of art.

Early life

Hokusai's date of birth is unclear, but is often stated as the 23rd day of the 9th month of the 10th year of the Hōreki era (in the old calendar, or 31 October 1760) to an artisan family, in the Katsushika district of Edo, Japan.[4] His childhood name was Tokitarō.[5] It is believed his father was Nakajima Ise mirror-maker for the shōgun.[5] His father never made Hokusai an heir, so it is possible that his mother was a concubine.[4] Hokusai began painting around the age of six, perhaps learning from his father, whose work included a painting of designs around mirrors.[4]

Hokusai was known by at least thirty names during his lifetime. While the use of multiple names was a common practice of Japanese artists of the time, his number of pseudonyms exceeds that of any other major Japanese artist. His name changes are so frequent, and so often related to changes in his artistic production and style, that they are used for breaking his life up into periods.[4]

At the age of 12, his father sent him to work in a bookshop and lending library, a popular institution in Japanese cities, where reading books made from woodcut blocks was a popular entertainment of the middle and upper classes.[6] At 14, he worked as an apprentice to a woodcarver, until the age of 18, when he entered the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō. Shunshō was an artist of ukiyo-e, a style of woodblock prints and paintings that Hokusai would master, and head of the so-called Katsukawa school.[5] Ukiyo-e, as practised by artists like Shunshō, focused on images of the courtesans (bijin-ga) and kabuki actors (yakusha-e) who were popular in Japan's cities at the time.[7]

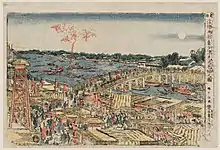

After a year, Hokusai's name changed for the first time, when he was dubbed Shunrō by his master. It was under this name that he published his first prints, a series of pictures of kabuki actors published in 1779. During the decade he worked in Shunshō's studio, Hokusai was married to his first wife, about whom very little is known except that she died in the early 1790s. He married again in 1797, although this second wife also died after a short time. He fathered two sons and three daughters with these two wives, and his youngest daughter Ei, also known as Ōi, eventually became an artist and his assistant.[7][8] Fireworks in the Cool of Evening at Ryogoku Bridge in Edo (c. 1788–89) dates from this period of Hokusai's life.[9]

Upon the death of Shunshō in 1793, Hokusai began exploring other styles of art, including European styles he was exposed to through French and Dutch copper engravings he was able to acquire.[7] He was soon expelled from the Katsukawa school by Shunkō, the chief disciple of Shunshō, possibly due to his studies at the rival Kanō school. This event was, in his own words, inspirational: "What really motivated the development of my artistic style was the embarrassment I suffered at Shunkō's hands."[10]

Hokusai also changed the subjects of his works, moving away from the images of courtesans and actors that were the traditional subjects of ukiyo-e. Instead, his work became focused on landscapes and images of the daily life of Japanese people from a variety of social levels. This change of subject was a breakthrough in ukiyo-e and in Hokusai's career.[7]

Middle period

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

The next period saw Hokusai's association with the Tawaraya School and the adoption of the name "Tawaraya Sōri". He produced many privately commissioned prints for special occasions (surimono), and illustrations for books of humorous poems (kyōka ehon) during this time. In 1798, Hokusai passed his name on to a pupil and set out as an independent artist, free from ties to a school for the first time, adopting the name Hokusai Tomisa.

By 1800, Hokusai was further developing his use of ukiyo-e for purposes other than portraiture. He had also adopted the name he would most widely be known by, Katsushika Hokusai, the former name referring to the part of Edo where he was born, the latter meaning 'north studio', in honour of the North Star, symbol of a deity important in his religion of Nichiren Buddhism.[11] That year, he published two collections of landscapes, Famous Sights of the Eastern Capital and Eight Views of Edo (modern Tokyo). He also began to attract students of his own, eventually teaching 50 pupils over the course of his life.[7]

He became increasingly famous over the next decade, both due to his artwork and his talent for self-promotion. During an Edo festival in 1804, he created an enormous portrait of the Buddhist prelate Daruma, said to be 200 square meters, using a broom and buckets full of ink.[12] Another story places him in the court of the shōgun Tokugawa Ienari, invited there to compete with another artist who practised more traditional brushstroke painting. Hokusai's painted blue curve on paper, then chased a chicken whose feet had been dipped in red paint across the image. He described the painting to the shōgun as a landscape showing the Tatsuta River with red maple leaves floating in it, winning the competition.[13]

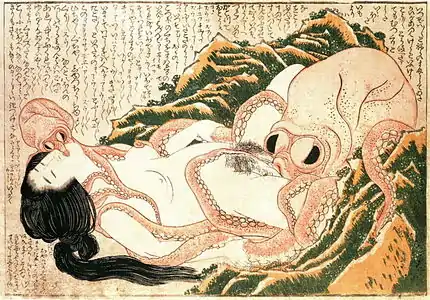

1807 saw Hokusai collaborate with the popular novelist Takizawa Bakin on a series of illustrated books. Especially popular was the fantasy novel Chinsetu Yumiharizuki (Strange Tales of the Crescent Moon) with Minamoto no Tametomo as the main character, and Hokusai gained fame with his creative and powerful illustrations, but the collaboration ended after seven works due to differences of opinion with Bakin regarding the illustrations.[14][15] The publisher, given the choice between keeping Hokusai or Bakin on the project, opted to keep Hokusai, emphasizing the importance of illustrations in printed works of the period.[16] Hokusai also created several albums of erotic art (shunga). His most famous image in this genre is The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife, which depicts a young woman entwined sexually with a pair of octopuses, from Kinoe no Komatsu, a three-volume book of shunga from 1814.[17]

Hokusai paid close attention to the production of his work. In letters during his involvement with Toshisen Ehon, a Japanese edition of an anthology of Chinese poetry, Hokusai wrote to the publisher that the blockcutter Egawa Tomekichi, with whom Hokusai had previously worked and whom he respected, had strayed from Hokusai's style in the cutting of certain heads. He also wrote directly to another blockcutter involved in the project, Sugita Kinsuke, stating that he disliked the Utagawa school style in which Kinsuke had cut the figure's eyes and noses and that amendments were needed for the final prints to be true to his style. In his letter, Hokusai included examples of both his style of illustrating eyes and noses and the Utagawa school style.[18]

In 1811, at the age of 51, Hokusai changed his name to Taito and entered the period in which he created the Hokusai Manga and various etehon, or art manuals.[5] These manuals beginning in 1812 with Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing, were intended as a convenient way to make money and attract more students. The first volume of Manga (meaning random drawings) was published in 1814 and was an immediate success.[19] By 1820, he had produced twelve volumes (with three more published posthumously) which include thousands of drawings of objects, plants, animals, religious figures, and everyday people, often with humorous overtones.[16]

On 5 October 1817, he painted the Great Daruma outside the Hongan-ji Nagoya Betsuin in Nagoya. This portrait in ink on paper measured 18 × 10.8 metres, and the event drew huge crowds. The feat was recounted in a popular song and he received the name "Darusen" or "Daruma Master"[20][21] Although the original was destroyed in 1945, Hokusai's promotional handbills from that time survived and are preserved at the Nagoya City Museum.

In 1820, Hokusai changed his name yet again, this time to "Iitsu," a change which marked the start of a period in which he secured fame as an artist throughout Japan. His most celebrated work, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, including the famous Great Wave off Kanagawa and Red Fuji was produced in the early 1830s. The results of Hokusai's perspectival studies in Manga can be seen here in The Great Wave where he uses what would have been seen as a western perspective to represent depth and volume.[22] It proved so popular that ten more prints were later added to the series. Among the other popular series of prints he made during this time are A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, Oceans of Wisdom and Unusual Views of Celebrated Bridges in the Provinces.[23] He also began producing a number of detailed individual images of flowers and birds (kachō-e), including the extraordinarily detailed Poppies and Flock of Chickens.[24]

Later life

The next period, beginning in 1834, saw Hokusai working under the name "Gakyō Rōjin" (画狂老人; "The Old Man Mad About Art").[25] It was at this time that he produced One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, another significant series,[26] generally considered "the masterpiece among his landscape picture books".[10]

In the colophon to this work, Hokusai writes:

From the age of six, I had a passion for copying the form of things and since the age of fifty I have published many drawings, yet of all I drew by my seventieth year there is nothing worth taking into account. At seventy-three years I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants. And so, at eighty-six I shall progress further; at ninety I shall even further penetrate their secret meaning, and by one hundred I shall perhaps truly have reached the level of the marvellous and divine. When I am one hundred and ten, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.[27]

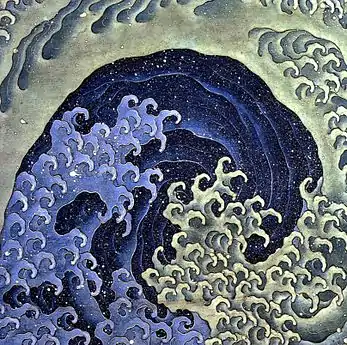

In 1839, a fire destroyed Hokusai's studio and much of his work. By this time, his career was beginning to fade as younger artists such as Andō Hiroshige became increasingly popular. At the age of 83, Hokusai traveled to Obuse in Shinano Province (now Nagano Prefecture) at the invitation of a wealthy farmer, Takai Kozan where he stayed for several years.[28] During his time in Obuse, he created several masterpieces, included the Masculine Wave and the Feminine Wave.[28] Between 1842 and 1843, in what he described as "daily exorcisms" (nisshin joma), Hokusai painted Chinese lions (shishi) every morning in ink on paper as a talisman against misfortune.[29][30]

Hokusai continued working almost until the end, painting The Dragon of Smoke Escaping from Mt Fuji[31] and Tiger in the Snow in early 1849.[32]

Constantly seeking to produce better work, he apparently exclaimed on his deathbed, "If only Heaven will give me just another ten years ... Just another five more years, then I could become a real painter." He died on 10 May 1849[33] and was buried at the Seikyō-ji in Tokyo (Taito Ward).[5] A haiku he composed shortly before his death reads: "Though as a ghost, I shall lightly tread, the summer fields."[34]

Dragon on the Higashimachi Festival Float, Obuse, 1844

Dragon on the Higashimachi Festival Float, Obuse, 1844 Feminine Wave, painted while living in Obuse, 1845

Feminine Wave, painted while living in Obuse, 1845 The Dragon of Smoke Escaping From Mount Fuji, painting, 1849

The Dragon of Smoke Escaping From Mount Fuji, painting, 1849 Tiger in the Snow, hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk, 1849

Tiger in the Snow, hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk, 1849

Selected works

.jpg.webp) Kirifuri waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke,

Kirifuri waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke,

from A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (1814), included in Kinoe no Komatsu, a three-volume book of shunga erotica

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (1814), included in Kinoe no Komatsu, a three-volume book of shunga erotica_Cuckoo_and_Azaleas.jpg.webp) Cuckoo and Azaleas, 1834

Cuckoo and Azaleas, 1834

from the Small Flower series Egrets from Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing

Egrets from Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing Carp Leaping up a Cascade

Carp Leaping up a Cascade The Ghost of Oiwa,

The Ghost of Oiwa,

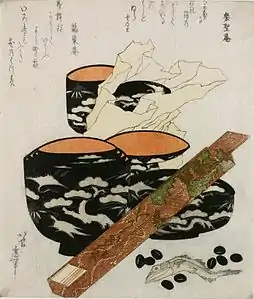

from One Hundred Ghost Tales Still Life, surimono print

Still Life, surimono print.jpg.webp)

Tenma Bridge in Setsu Province,

Tenma Bridge in Setsu Province,

from Rare Views of Famous Japanese Bridges Chōshi in Shimosha,

Chōshi in Shimosha,

from Oceans of Wisdom "The Big Wave" from One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji

"The Big Wave" from One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji%252C_Veld_in_de_Owari_provincie_(1829-33).jpg.webp) Amida Falls,

Amida Falls,

from A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls

Influences on art and culture

Hokusai had achievements in various fields as an artist. He made designs for book illustrations and woodblock prints, sketches, and painting for over 70 years.[35] Hokusai was an early experimenter with western linear perspective among Japanese artists.[36] Hokusai himself was influenced by Sesshū Tōyō and other styles of Chinese painting.[37] His influences stretched across the globe to his western contemporaries in nineteenth-century Europe with Japonism, which started with a craze for collecting Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e, of which some of the first samples were to be seen in Paris, when in about 1856, the French artist Félix Bracquemond first came across a copy of the sketchbook Hokusai Manga at the workshop of his printer.

He influenced the Impressionism movement, with themes echoing his work appearing in the work of Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, as well as Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil in Germany. Many European artists collected his woodcuts such as Degas, Gauguin, Klimt, Franz Marc, August Macke, Manet, and van Gogh.[38] Degas said of him, "Hokusai is not just one artist among others in the Floating World. He is an island, a continent, a whole world in himself."[39] Hermann Obrist's whiplash motif, or Peitschenhieb, which came to exemplify the new movement, is visibly influenced by Hokusai's work.

Even after his death, exhibitions of his artworks continue to grow. In 2005, Tokyo National Museum held a Hokusai exhibition which had the largest number of visitors of any exhibit there that year.[40] Several paintings from the Tokyo exhibition were also exhibited in the United Kingdom. The British Museum held the first exhibition of Hokusai's later year artworks including 'The Great Wave' in 2017.[41]

Hokusai inspired the Hugo Award–winning short story by science fiction author Roger Zelazny, "24 Views of Mt. Fuji, by Hokusai", in which the protagonist tours the area surrounding Mount Fuji, stopping at locations painted by Hokusai. A 2011 book on mindfulness closes with the poem "Hokusai Says" by Roger Keyes, preceded with the explanation that "[s]ometimes poetry captures the soul of an idea better than anything else."[42]

In the 1985 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Richard Lane characterizes Hokusai as "since the later 19th century [having] impressed Western artists, critics and art lovers alike, more, possibly, than any other single Asian artist".[43]

'Store Selling Picture Books and Ukiyo-e' by Hokusai shows how ukiyo-e during the time was actually sold; it shows how these prints were sold at local shops, and ordinary people could buy ukiyo-e. Unusually in this image, Hokusai used a hand-colored approach instead of using several separated woodblocks.

Notes

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric. (2005). "Hokusai" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 345.

- Smith

- Kleiner, Fred S. and Christin J. Mamiya, (2009). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives, p. 115.

- Weston, p. 116

- Nagata

- Weston, pp. 116–117

- Weston, p. 117

- "葛飾, 応為 カツシカ, オウイ" (in Japanese). CiNii. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Calza (2003), p. 426

- Nagata, Seiji. Hokusai: Genius of the Japanese Ukiyo-e. Kodansha, Tokyo, 1999.

- The name "Hokusai" (北斎 "North Studio") is an abbreviation of "Hokushinsai" (北辰際 "North Star Studio"). In Nichiren Buddhism the North Star is revered as a deity known as Myōken.

- Calza (2003), p. 128

- Weston, pp. 117–118

- 北斎生誕260年記念 北斎資格のマジック Hokusai kan

- 曲亭馬琴と葛飾北斎 Hokusai kan

- Weston, p. 118

- Calza (2003), p. 455

- Tinios, Ellis (June 2015). "Hokusai and his Blockcutters". Print Quarterly. XXXII (2): 186–191.

- Hillier, Jack R. (1980). The Art of Hokusai in Book Illustration. London: Sotheby Parke Bernet; Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. p. 107

- A shortened form of Daruma Sensei.

- Calza (2003), p. 192

- Screech, Timon (2012). "Hokusai's Lines of Sight". Mechademia. 7: 107. doi:10.1353/mec.2012.0009. JSTOR 41601844. S2CID 119865798.

- Weston, pp. 118–119

- Weston, p. 119

- Hokusai Heaven retrieved 27 March 2009 Archived 3 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Fugaku hyakkei (One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji)". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. December 21, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Calza, Gian Carlo. "Hokusau: A Universe" in Hokusai, p. 7. Phaidon

- "Welcome to the World of Hokusai, an "Old Man Mad About Painting"!". Hokusai Kan. Hokusai Museum. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Machotka, Ewa (2009). Visual Genesis of Japanese National Identity: Hokusai's Hyakunin Isshu. Peter Lang. ISBN 9789052014821.

- "Fine Japanese Art, lot 252". Bonhams. 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- "The Dragon of Smoke Escaping From Mount Fuji, 1849 by Hokusai". KatsushikaHokusai.com. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- Tsuji Nobou in Calza (2003), p. 72

- (18th day of the 4th month of the 2nd year of the Kaei era by the old calendar)

- Tsuji Nobou in Calza (2003), p. 72

- Finley, Carol (1 January 1998). Art of Japan: Wood-block Color Prints. Lerner Publications. ISBN 9780822520771.

- "Paintings as architectural space:"Guided Tours" by Cezanne and Hokusai". 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Daniel Atkison and Leslie Stewart. "Life and Art of Katsushika Hokusai" in From the Floating World: Part II: Japanese Relief Prints, catalogue of an exhibition produced by California State University, Chico. Retrieved 9 July 2007; Archived 8 November 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- Rhodes, David (November 2011). "Hokusai Retrospective". The Brooklyn Rail.

- "How, after death, Hokusai changed art history". Phaidon. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Brown, Kendall H. (13 August 2007). "Hokusai and His Age: Ukiyo-e Painting, Printmaking and Book Illustration in Late Edo Japan (review)". The Journal of Japanese Studies. 33 (2): 521–525. doi:10.1353/jjs.2007.0048. ISSN 1549-4721. S2CID 143267375.

- Carelli, Francesco (2018). "Hokusai: beyond the Great Wave". London Journal of Primary Care. 10 (4): 128–129. doi:10.1080/17571472.2018.1486504. PMC 6074688. PMID 30083250.

- Mark Williams and Danny Penman (2011). Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World, pp. 249, 250–251. The poem is also at Hokusai Says – Gratefulness.org.

- Lane, Richard (1985). "Hokusai", Encyclopædia Britannica, v. 5, p. 973.

References

- Calza, Gian Carlo (2003). Hokusai. Phaidon. ISBN 0714844578.

- Lane, Richard (1978). Images from the Floating World: The Japanese Print. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211447-1; OCLC 5246796.

- Nagata, Seiji (1995). Hokusai: Genius of the Japanese Ukiyo-e. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

- Ray, Deborah Kogan (2001). Hokusai: The Man Who Painted a Mountain. New York: Frances Foster Books. ISBN 0-374-33263-0.

- Smith, Henry D. II (1988). Hokusai: One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji. New York: George Braziller, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 0-8076-1195-6.

- Weston, Mark (1999). Giants of Japan: The Lives of Japan's Most Influential Men and Women. New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 1-56836-286-2.

Further reading

General biography

- Bowie, Theodore (1964). The Drawings of Hokusai. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- Forrer, Matthi (1988). Hokusai Rizzoli, New York. ISBN 0-8478-0989-7.

- Forrer, Matthi; van Gulik, Willem R., and Kaempfer, Heinz M. (1982). Hokusai and His School: Paintings, Drawings and Illustrated Books. Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem. ISBN 90-70216-02-7

- Hillier, Jack (1955). Hokusai: Paintings, Drawings and Woodcuts. Phaidon, London.

- Hillier, Jack (1980). Art of Hokusai in Book Illustration. Sotheby Publications, London. ISBN 0-520-04137-2.

- Lane, Richard (1989). Hokusai: Life and Work. E.P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24455-7.

- van Rappard-Boon, Charlotte (1982). Hokusai and his School: Japanese Prints c. 1800–1840 (Catalogue of the Collection of Japanese Prints, Rijksmuseum, Part III). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Specific works of art

For readers who want more information on specific works of art by Hokusai, these particular works are recommended.

- Hillier, Jack, and Dickens, F.W. (1960). Fugaku Hiyaku-kei (One Hundred Views of Fuji by Hokusai). Frederick, New York.

- Kondo, Ichitaro (1966). Trans. Terry, Charles S. The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai. East-West Center, Honolulu.

- Michener, James A. (1958). The Hokusai Sketch-Books: Selections from the 'Manga'. Charles E. Tuttle, Rutland.

- Morse, Peter (1989). Hokusai: One Hundred Poets. George Braziller, New York. ISBN 0-8076-1213-8.

- Narazaki, Muneshige (1968). Trans. Bester, John. Masterworks of Ukiyo-E: Hokusai – The Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji. Kodansha, Tokyo.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hokusai |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Katsushika Hokusai. |

- Hokusai at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Hokusai-Museum in Obuse, Japan

- Hokusai website

- Works by Hokusai at Faded Page (Canada)