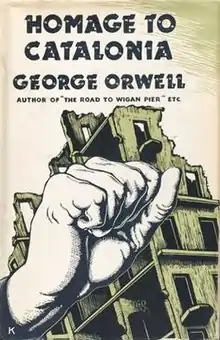

Homage to Catalonia

Homage to Catalonia is George Orwell's personal account of his experiences and observations fighting for the POUM militia of the Republican army during the Spanish Civil War. The war was one of the defining events of his political outlook and a significant part of what led him to write in 1946, "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for Democratic Socialism, as I understand it."[1]

| |

| Author | George Orwell |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Non-fiction, political |

| Publisher | Secker and Warburg (London) |

Publication date | April 1938 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 368 (paperback) 248 (hardback) |

| Preceded by | The Road to Wigan Pier |

| Followed by | Coming Up for Air |

The first edition was published in the United Kingdom in 1938. The book was not published in the United States until February 1952, when it appeared with an influential preface by Lionel Trilling. The only translation published in Orwell's lifetime was into Italian, in December 1948.[2] A French translation by Yvonne Davet—with whom Orwell corresponded, commenting on her translation and providing explanatory notes—in 1938–39, was not published until five years after Orwell's death.[3]

Overview

.svg.png.webp)

|

Initial Nationalist zone – July 1936

Nationalist advance until September 1936

Nationalist advance until October 1937

Nationalist advance until November 1938

Nationalist advance until February 1939

Last area under Republican control

|

|

Orwell served as a private, a corporal (cabo) and—when the informal command structure of the militia gave way to a conventional hierarchy in May 1937—as a lieutenant, on a provisional basis,[4] in Catalonia and Aragon from December 1936 until June 1937. In June 1937, the leftist political party with whose militia he served (the POUM, the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification, an anti-Stalinist communist party) was declared an illegal organisation, and Orwell was consequently forced to flee.

Having arrived in Barcelona on 26 December 1936, Orwell told John McNair, the Independent Labour Party's (ILP) representative there, that he had "come to Spain to join the militia to fight against Fascism." He also told McNair that "he would like to write about the situation and endeavour to stir working class opinion in Britain and France." McNair took him to the POUM barracks, where Orwell immediately enlisted.[5] "Orwell did not know that two months before he arrived in Spain, the [Soviet law enforcement agency] NKVD's resident in Spain, Aleksandr Orlov, had assured NKVD Headquarters, 'the Trotskyist organisation POUM can easily be liquidated'—by those, the Communists, whom Orwell took to be allies in the fight against Franco."[5]

By his own admission, it was somewhat by chance that Orwell joined the POUM, rather than the far larger Comintern-run International Brigades. Orwell had been told that he would not be permitted to enter Spain without some supporting documents from a British left-wing organisation, and he had first sought the assistance of the British Communist Party and put his request directly to its leader, Harry Pollitt. Pollitt "seems to have taken an immediate dislike to him ... and soon concluded that his visitor was 'politically unreliable.'"[6] Orwell then telephoned the headquarters of the ILP, and its officials agreed to help him. The party was willing to accredit him as a correspondent for the New Leader, the ILP's weekly paper with which he was familiar, and thus provided the means for him to go legitimately to Spain.[7] The ILP issued him a letter of introduction to their representative in Barcelona and was affiliated with the POUM. Orwell's experiences, culminating in his and his wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy's narrow escape from the communist purges in Barcelona in June 1937,[8] greatly increased his sympathy for the POUM and, while not affecting his moral and political commitment to socialism, made him a lifelong anti-Stalinist.

Orwell served on the Aragon front for 115 days. It was not until the end of April 1937 that he was granted leave and was able to see his wife Eileen in Barcelona again. Eileen wrote on 1 May that she found him, "a little lousy, dark brown, and looking really very well." At this point he was convinced that he would have the chance to see more action if he joined the International Brigades and fought with them on the Madrid front; his attitude was still one of exasperation in the face of the rivalries between the various factions. This "changed dramatically in the first week of May when he found himself and his comrades under fire not from the Nationalist enemy but from their left-wing 'allies'" in the fighting that followed the government effort to take control of the Telephone Exchange.[9] The Spanish government was seeking to assert direct control on Barcelona which, as part of Revolutionary Catalonia, was chiefly in the hands of the anarchists. The government decided to occupy the telephone building and to disarm the workers; the anarcho-syndicalist CNT staff resisted, and street fighting followed, in which Orwell was caught up. The struggle was called off by the CNT leaders after four days. Large numbers of government reinforcements arrived from Valencia.[10]

On 17 May 1937, Largo Caballero resigned and Juan Negrín became prime minister. The NKVD-controlled secret police pursued its persecution of those who opposed the Moscow line. Antony Beevor notes that on 16 June, when the POUM was declared illegal, "the Communists turned its headquarters in Barcelona into a prison for 'Trotskyists' ... leaders were handed over to NKVD operatives and taken to a secret prison in Madrid ... Andreu Nin taken to Alcalá de Henares, where he was interrogated from 18 to 21 June ... he was then moved to a summer house outside the city which belonged to the wife of Hidalgo de Cisneros and tortured to death ... Diego Abad de Santillan remarked; 'Whether Juan Negrín won with his communist cohorts, or Franco won with his Italians and Germans, the results would be the same for us.'"[11] At the front, Orwell was shot through the throat by a sniper on 20 May 1937 and nearly killed. He wrote in Homage to Catalonia that people frequently told him a man who is hit through the neck and survives is the luckiest creature alive, but that he personally thought "it would be even luckier not to be hit at all." After having his wounds dressed at a first aid post about half a mile from the front line, he was transferred to Barbastro and then to Lérida, where he received only an external treatment of his wound. On the 27th he was transferred to Tarragona, and on the 29th from there to Barcelona. On 23 June 1937, Orwell and Eileen, with John McNair and Stafford Cottman, a young English POUM militiaman, boarded the morning train from Barcelona to Paris. They safely crossed into France. Sir Richard Rees later wrote that the strain of her experience in Barcelona showed clearly on Eileen's face: "In Eileen Blair I had seen for the first time the symptoms of a human being living under a political terror."[12] On 13 July 1937, a deposition was presented to the Tribunal for Espionage & High Treason, Valencia, charging the Orwells with 'rabid Trotskyism' and being agents of the POUM.[13]

Orwell and Eileen returned to England. After nine months of animal husbandry and writing up Homage to Catalonia at their cottage at Wallington, Hertfordshire, Orwell's health declined, and he had to spend several months at a sanatorium in Aylesford, Kent. The trial of the leaders of the POUM and of Orwell (in his absence) took place in Barcelona, in October and November 1938. Observing events from French Morocco, Orwell wrote that they were "only a by-product of the Russian Trotskyist trials and from the start every kind of lie, including flagrant absurdities, has been circulated in the Communist press."[14] Barcelona fell to Franco's forces on 26 January 1939.[15]

Because of the book's criticism of the Stalinists in Spain, it was rejected by Gollancz, who had previously published all Orwell's books: "Gollancz is of course part of the Communism-racket," Orwell wrote to Rayner Heppenstall in July 1937. Orwell finally found a sympathetic publisher in Frederic Warburg. Warburg was willing to publish books by the dissident left, that is, by socialists hostile to Stalinism.[8]

The book was finally published in April 1938, but according to John Newsinger, "made virtually no impact whatsoever and by the outbreak of war with Germany had sold only 900 copies"; Newsinger maintained that "the Communist vendetta against the book" was maintained as recently as 1984, when Lawrence and Wishart published Inside the Myth, a collection of essays "bringing together a variety of standpoints hostile to Orwell in an obvious attempt to do as much damage to his reputation as possible."[8]

Summary of chapters

The following summary is based on a later edition of the book which contains some amendments that Orwell requested: two chapters (formerly chapters five and eleven) describing the politics of the time were moved to appendices. Orwell felt that these chapters should be moved so that readers could ignore them if they wished; the chapters, which became appendices, were journalistic accounts of the political situation in Spain, and Orwell felt these were out of place in the midst of the narrative.

Chapter one

The book begins in late December 1936. Orwell describes the atmosphere in Barcelona as it appears to him. "The anarchists were still in virtual control of Catalonia and the revolution was still in full swing ... It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle ... every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle ... every shop and café had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized." "The Anarchists" (referring to the Spanish CNT and FAI) were "in control", tipping was prohibited by workers themselves, and servile forms of speech, such as "Señor" or "Don", were abandoned. He goes on to describe the scene at the Lenin Barracks (formerly the Lepanto Barracks) where militiamen were given "what was comically called 'instruction'" in preparation for fighting at the front.

He describes the deficiencies of the POUM workers' militia, the absence of weapons, the recruits mostly boys of sixteen or seventeen ignorant of the meaning of war, half-complains about the sometimes frustrating tendency of Spaniards to put things off until "mañana" (tomorrow), notes his struggles with Spanish (or more usually, the local use of Catalan). He praises the generosity of the Catalan working class. Orwell leads to the next chapter by describing the "conquering-hero stuff"—parades through the streets and cheering crowds—that the militiamen experienced at the time he was sent to the Aragón front.

Chapter two

In January 1937, Orwell's centuria arrives in Alcubierre, just behind the line fronting Zaragoza. He sketches the squalor of the region's villages and the "Fascist deserters" indistinguishable from themselves. On the third day rifles are handed out. Orwell's "was a German Mauser dated 1896 ... it was corroded and past praying for." The chapter ends on his centuria's arrival at trenches near Zaragoza and the first time a bullet nearly hit him. To his dismay, instinct made him duck.

Chapter three

Orwell, in the hills around Zaragoza, describes the "mingled boredom and discomfort of stationary warfare," the mundaneness of a situation in which "each army had dug itself in and settled down on the hill-tops it had won." He praises the Spanish militias for their relative social equality, for their holding of the front while the army was trained in the rear, and for the "democratic 'revolutionary' type of discipline ... more reliable than might be expected." "'Revolutionary' discipline depends on political consciousness—on an understanding of why orders must be obeyed; it takes time to diffuse this, but it also takes time to drill a man into an automaton on the barrack-square." Throughout the chapter Orwell describes the various shortages and problems at the front—firewood ("We were between two and three thousand feet above sea-level, it was mid winter and the cold was unspeakable"), food, candles, tobacco, and adequate munitions—as well as the danger of accidents inherent in a badly trained and poorly armed group of soldiers.

Chapter four

After some three weeks at the front, Orwell and the other English militiaman in his unit, Williams, join a contingent of fellow Englishmen sent out by the Independent Labour Party to a position at Monte Oscuro, within sight of Zaragoza. "Perhaps the best of the bunch was Bob Smillie—the grandson of the famous miners' leader—who afterwards died such an evil and meaningless death in Valencia." In this new position he witnesses the sometimes propagandistic shouting between the Rebel and Loyalist trenches and hears of the fall of Málaga. "... every man in the militia believed that the loss of Malaga was due to treachery. It was the first talk I had heard of treachery or divided aims. It set up in my mind the first vague doubts about this war in which, hitherto, the rights and wrongs had seemed so beautifully simple." In February, he is sent with the other POUM militiamen 50 miles to make a part of the army besieging Huesca; he mentions the running joke phrase, "Tomorrow we'll have coffee in Huesca," attributed to a general commanding the Government troops who, months earlier, made one of many failed assaults on the town.

Chapter five

Orwell complains, in Chapter Five, that on the eastern side of Huesca, where he was stationed, nothing ever seemed to happen—except the onslaught of spring, and, with it, lice. He was in a ("so-called") hospital at Monflorite for ten days at the end of March 1937 with a poisoned hand that had to be lanced and put in a sling. He describes rats that "really were as big as cats, or nearly" (in Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, the protagonist Winston Smith has a phobia of rats that Orwell himself shared to a lesser degree). He makes reference to the lack of "religious feeling, in the orthodox sense," and that the Catholic Church was, "to the Spanish people, at any rate in Catalonia and Aragon, a racket, pure and simple." He muses that Christianity may have, to some extent, been replaced by Anarchism. The latter portion of the chapter briefly details various operations in which Orwell took part: silently advancing the Loyalist frontline by night, for example.

Chapter six

One of these operations, which in Chapter Five had been postponed, was a "holding attack" on Huesca, designed to draw the Nationalist troops away from an Anarchist attack on "the Jaca road." It is described herein. It is one of the most significant military actions that Orwell participates in during his entire time in Spain. Orwell notes the offensive of that night where his group of fifteen captured a Nationalist position, but then retreated to their lines with captured rifles and ammunition. However, despite these finds, Orwell and his group were forced to pull back before they could secure a large telescope they had discovered in a machine gun case, something more badly needed to their side than any single weapon. However, the diversion was successful in drawing troops from the Anarchist attack. The chapter ends with Orwell lamenting that even now he still is upset about losing the telescope.[17]

Chapter seven

This chapter reads like an interlude. Orwell shares his memories of the 115 days he spent on the war front, and its influence on his political ideas, "... the prevailing mental atmosphere was that of Socialism ... the ordinary class-division of society had disappeared to an extent that is almost unthinkable in the money-tainted air of England ... the effect was to make my desire to see Socialism established much more actual than it had been before." By the time he left Spain, he had become a "convinced democratic Socialist." The chapter ends with Orwell's arrival in Barcelona on the afternoon of 26 April 1937. "And after that the trouble began."

Chapter eight

Orwell details noteworthy changes in the social and political atmosphere of Barcelona when he returns after three months at the front. He describes a lack of revolutionary atmosphere and the class division that he had thought would not reappear, i.e., with visible division between rich and poor and the return of servile language. Orwell had been determined to leave the POUM, and confesses here that he "would have liked to join the Anarchists," but instead sought a recommendation to join the International Column, so that he could go to the Madrid front. The latter half of this chapter is devoted to describing the conflict between the anarchist CNT and the socialist Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) and the resulting cancellation of the May Day demonstration and the build-up to the street fighting of the Barcelona May Days. "It was the antagonism between those who wished the revolution to go forward and those who wished to check or prevent it—ultimately, between Anarchists and Communists."

Chapter nine

Orwell relates his involvement in the Barcelona street fighting that began on 3 May when the Government Assault Guards tried to take the Telephone Exchange from the CNT workers who controlled it. For his part, Orwell acted as part of the POUM, guarding a POUM-controlled building. Although he realises that he is fighting on the side of the working class, Orwell describes his dismay at coming back to Barcelona on leave from the front only to get mixed up in street fighting. Assault Guards from Valencia arrive—"All of them were armed with brand-new rifles ... vastly better than the dreadful old blunderbusses we had at the front." The Communist-controlled Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia newspapers declare POUM to be a disguised Fascist organisation—"No one who was in Barcelona then ... will forget the horrible atmosphere produced by fear, suspicion, hatred, censored newspapers, crammed jails, enormous food queues, and prowling gangs ...." In his second appendix to the book, Orwell discusses the political issues at stake in the May 1937 Barcelona fighting, as he saw them at the time and later on, looking back.

Chapter ten

Here he begins with musings on how the Spanish Civil War might turn out. Orwell predicts that the "tendency of the post-war Government ... is bound to be Fascistic." He returns to the front, where he is shot through the throat by a sniper,[18] an injury that takes him out of the war. After spending some time in a hospital in Lleida, he was moved to Tarragona where his wound was finally examined more than a week after he'd left the front.

Chapter eleven

Orwell tells us of his various movements between hospitals in Siétamo, Barbastro, and Monzón while getting his discharge papers stamped, after being declared medically unfit. He returns to Barcelona only to find that the POUM had been "suppressed": it had been declared illegal the very day he had left to obtain discharge papers and POUM members were being arrested without charge. "The attack on Huesca was beginning ... there must have been numbers of men who were killed without ever learning that the newspapers in the rear were calling them Fascists. This kind of thing is a little difficult to forgive." He sleeps that night in the ruins of a church; he cannot go back to his hotel because of the danger of arrest.

.jpg.webp)

Chapter twelve

This chapter describes his visits accompanied by his wife to Georges Kopp, unit commander of the ILP Contingent while Kopp was held in a Spanish makeshift jail—"really the ground floor of a shop." Having done all he could to free Kopp, ineffectively and at great personal risk, Orwell decides to leave Spain. Crossing the Pyrenees frontier, he and his wife arrived in France "without incident".

Appendix one

The broader political context in Spain and the revolutionary situation in Barcelona at the time is discussed. The political differences among the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC—entirely under Communist control and affiliated to the Third International), the anarchists, and the POUM, are considered.

Appendix two

An attempt to dispel some of the myths in the foreign press at the time (mostly the pro-Communist press) about the May Days, the street fighting that took place in Catalonia in early May 1937. This was between anarchists and POUM members, against Communist/government forces which sparked off when local police forces occupied the Telephone Exchange, which had until then been under the control of CNT workers. He relates the suppression of the POUM on 15–16 June 1937, gives examples of the Communist Press of the world—(Daily Worker, 21 June, "Spanish Trotskyists Plot With Franco"), indicates that Indalecio Prieto hinted, "fairly broadly ... that the government could not afford to offend the Communist Party while the Russians were supplying arms." He quotes Julián Zugazagoitia, the Minister of the Interior; "We have received aid from Russia and have had to permit certain actions which we did not like."

In a letter he wrote in August 1938[20] protesting against the treatment of a number of members of the Executive Committee of the POUM who were shortly to be put on trial on the charge of espionage in the Fascist cause, Orwell repeated Zugazagoitia's words. An editorial note on the letter (taken from Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War 704) adds: "During a cabinet meeting, 'Zugazagoitia demanded if his jurisdiction as Minister of the Interior were to be limited by Russian policemen' ... Had they been able to purchase and transport good arms from US, British, and French manufacturers, the socialist and republican members of the Spanish government might have tried to cut themselves loose from Stalin."

Reviews

Contemporary reviews of the book were mixed. Notably positive reviews came from Geoffrey Gorer in Time and Tide, and from Philip Mairet in the New English Weekly. Geoffrey Gorer concluded, "Politically and as literature it is a work of first-class importance." Philip Mairet observed, "It shows us the heart of innocence that lies in revolution; also the miasma of lying that, far more than the cruelty, takes the heart out of it." Hostile notices came from The Tablet, where a critic wondered why Orwell had not troubled to get to know Fascist fighters and enquire about their motivations, and from The Times Literary Supplement and The Listener, "the first misrepresenting what Orwell had said and the latter attacking the POUM, but never mentioning the book."[21] John Langdon-Davies wrote in the Communist Party's Daily Worker that "the value of the book is that it gives an honest picture of the sort of mentality that toys with revolutionary romanticism but shies violently at revolutionary discipline. It should be read as a warning."[22] Some Conservative and Catholic opponents of the Spanish Republic felt vindicated by Orwell's attack on the role of the Communists in Spain; The Spectator's review concluded that this "dismal record of intrigue, injustice, incompetence, quarrelling, lying communist propaganda, police spying, illegal imprisonment, filth and disorder," was evidence that the Republic deserved to fall.[23] A mixed review was supplied by V. S. Pritchett who called Orwell naïve about Spain but added that "no one excels him in bringing to the eyes, ears and nostrils the nasty ingredients of fevered situations; and I would recommend him warmly to all who are concerned about the realities of personal experience in a muddled cause."[24] Franz Borkenau, in a letter to Orwell of June 1938, called the book, together with his own The Spanish Cockpit, a complete "picture of the revolutionary phase of the Spanish War."

According to Raymond Carr:[25]

The Spanish Civil war produced a spate of bad literature. Homage to Catalonia is one of the few exceptions and the reason is simple. Orwell was determined to set down the truth as he saw it. This was something that many writers of the Left in 1936–39 could not bring themselves to do. Orwell comes back time and time again in his writings on Spain to those political conditions in the late thirties which fostered intellectual dishonesty: the subservience of the intellectuals of the European Left to the Communist 'line', especially in the case of the Popular Front in Spain where, in his view, the party line could not conceivably be supported by an honest man. Only a few strong souls, Victor Serge and Orwell among them, could summon up the courage to fight the whole tone of the literary establishment and the influence of Communists within it. Arthur Koestler quoted to an audience of Communist sympathizers Thomas Mann's phrase, 'In the long run a harmful truth is better than a useful lie'. The non-Communists applauded; the Communists and their sympathizers remained icily silent. ... It is precisely the immediacy of Orwell's reaction that gives the early sections of Homage its value for the historian. Kaminski, Borkenau, Koestler came with a fixed framework, the ready-made contacts of journalist intellectuals. Orwell came with his eyes alone.

After years of neglect Homage to Catalonia re-emerged in the 1950s, following on from the success of Orwell's later books. The publication in 1952 of the first US edition (by Harcourt, Brace, of New York) with an influential introduction by Lionel Trilling, "elevated Orwell to the rank of a secular saint." Another twist arrived in the late 1960s when the book "found new readers in an age of student radicalism and guerrilla struggle—Orwell being seen as an early Che Guevara and [the book] now appeared to offer a premonition of the Soviet suppression of the 1968 Prague Spring."[26] The book was praised by Noam Chomsky.[27] Its popularity has continued, notably with Ken Loach's heavily Orwell-influenced film Land and Freedom. Republished by Penguin Books in Britain in 1962, it has never been out of print since, and remains far better known than Franz Borkenau's The Spanish Cockpit, a book Orwell himself had called, in July 1937, "the best book yet written on the subject" of the Spanish war.[28]

Aftermath

Homage to Catalonia was commercially unsuccessful, only selling 638 copies,[30] but Barcelona under the Anarchists would remain with Orwell. "No one who was in Spain during the months when people still believed in the revolution will ever forget that strange and moving experience. It has left something behind that no dictatorship, not even Franco's, will be able to efface."[31] In the words of a recent biographer, Gordon Bowker, "the people that had effaced that reality, the Soviet Communists, now had an implacable enemy they would come to regret having made." Christopher Hitchens: "The narrative core of Homage to Catalonia, it might be argued, is a series of events that occurred in and around the Barcelona telephone exchange in early May 1937. Orwell was a witness to these events, by the relative accident of his having signed up with the militia of the anti-Stalinist POUM upon arriving in Spain ... he became convinced that he had been the spectator of a full-blown Stalinist putsch ... Moreover, he came to understand that much of the talk about discipline and unity was a rhetorical shield for the covert Stalinization of the Spanish Republic."[32]

On 26 April 1937 when Orwell and his ILP comrades had returned to Barcelona on their leave they had been shocked to see how things had changed. The revolutionary atmosphere of four months earlier had all but evaporated, and old class divisions been reasserted. Similarly, as he headed for the French border on the train to Port Bou, Orwell noticed another symptom of the change since his arrival—the train on which classes had been abolished now had both first-class compartments and a dining car. Bowker reports that "Orwell mused that coming into Spain the previous year, bourgeois-looking people would be turned back at the border by Anarchist guards; now looking bourgeois gave one easy passage".[33] A simple hostility to Stalinist Communism became a "deep-dyed loathing of it". After reviewing Koestler's best-selling Darkness at Noon, Orwell decided that fiction was the best way to describe totalitarianism. Animal Farm, "his scintillating 1944 satire on Stalinism",[34][30] would be part of his response to the Spanish betrayal. "He had learned a hard lesson, especially about the new political Europe. Totalitarianism, the new creed of 'the streamlined men' of Fascism and Communism, was a new manifestation of Orwell's old Catholic enemy, the doctrine of Absolutism ... the ghost of Torquemada had arisen, imprisonment without trial, confessions extracted under torture with summary executions to follow."[35] "The essential fact about a totalitarian regime is that it has no laws. People are not punished for specific offences, but because they are considered to be politically or intellectually undesirable. What they have done or not done is irrelevant."[36]

Even after Hitler had repudiated his non-aggression pact with Stalin by launching Operation Barbarossa and most left-wing intellectuals were to "laud the virtues of the Soviet Union at the tops of their voices [and] even on the right, keeping Uncle Joe sweet was regarded as mandatory—Orwell went on insisting that the Soviet regime was a tyranny. Even as the Red Army battled the Panzers to a standstill on the outskirts of Moscow. At this distance, it is hard to imagine what a lonely line this was to take. But when it came to a principle Orwell was the sort of man who would rather shiver in solitude than hold his tongue."[37]

Apart from the betrayal of the POUMists, the terror and the murder of Nin and Smillie, Orwell had been depressed by the attitude of the British press. "In Spain ... I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts ... I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but of what ought to have happened according to various party lines."[38] Carr writes, "He was appalled at the treatment of the May days as a 'Trotskyist Revolt' in papers like the News Chronicle which simply swallowed uncritically the Communist line; or Ralph Bates' report in The New Republic that POUM militiamen were playing football with Fascist troops ... Given this supresio vero by interested parties, how could true history be written? Propaganda would pass as truth; 'facts' could be manipulated. Those who monopolized communication could create their own history after the event—the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four."[39] Orwell attacked sections of the left wing press for suppressing the truth about Spain, indicting the Communists for instigating a "reign of terror"; and he never forgave Kingsley Martin, the editor of the New Statesman who turned down his articles on the Spanish Civil War on the grounds that they "could cause trouble." Malcolm Muggeridge remembered: "Once when we were lunching at a Greek restaurant in Percy Street he asked me if I would mind changing places. I readily agreed but asked him why. He said that he just couldn't bear to look at Kingsley Martin's corrupt face, which, as Kingsley was lunching at an adjoining table, was unavoidable from where he had been sitting before."[40] "Ten years ago it was almost impossible to get anything printed in favour of Communism; today it is almost impossible to get anything printed in favour of Anarchism or 'Trotskyism'," Orwell wrote bitterly in 1938.[41]

Yet Orwell "had felt what socialism could be like"[42] and, according to Bowker, unlike the writer John Dos Passos for example, "who also had a friend killed in custody by the SIM (Servicio de Investigación Militar/Spanish Secret Police) in Spain, and reacted by deserting the Communists and shifting decidedly to the right, Orwell never did abandon his socialism: if anything, his Spanish experience strengthened it."[43] In a letter to Cyril Connolly, written on 8 June 1937, Orwell said, "At last I really believe in Socialism which I never did before". A decade later he wrote: "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it."[1]

The Crystal Spirit

In the opening lines of the book, Orwell describes an Italian militiaman he met at the Lenin Barracks and to whose memory Orwell would dedicate a poem "nearly two years later, when the war was visibly lost". The poem was included in Orwell's 1942 essay "Looking Back on the Spanish War", published in New Road in 1943.[44]

The closing phrase of the poem, "No bomb that ever burst shatters the crystal spirit", was later taken by George Woodcock for the title of his Governor General's Award-winning critical study of Orwell and his work, The Crystal Spirit (1966).[45]

See also

- Anarchist Catalonia

- Bibliography of George Orwell

- ILP Contingent described in Homage to Catalonia

- Les grands cimetières sous la lune

- Spanish Revolution

- William Herrick 'an American Orwell', also disillusioned by Stalinism in Spain

References

- Rodden, John (2007). The Cambridge Companion to George Orwell. Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-521-67507-9.

- Omaggio alla Catalogna, translated by Giorgio Monicelli (Mondadori, Verona, December 1948), The Lost Orwell, p. 124.

- Facing Unpleasant Facts, 1937–39, Secker & Warburg, 1998, p. xvi. ISBN 0-436-20538-6.

- Shelden, Michael. Orwell. pp. 280, 293.

- Orwell in Spain. Penguin Books. 2001. p. 6.

- Shelden, Michael. Orwell, The Authorised Biography. p. 274.

- Stansky, Peter; Abrahams, William. Orwell: The Transformation. p. 200.

- Newsinger, John (Spring 1994). "Orwell and the Spanish Revolution". International Socialism Journal (62).

- Shelden, Michael. Orwell. p. 291.

- Brockway, Fenner (1942). Inside the Left. Reprinted in Orwell Remembered, p. 156.

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain, Chapter 23, "The Civil War within the Civil War"

- Rees, Richard (1961). George Orwell: Fugitive from the camp of victory. p. 147.

- Facing Unpleasant Facts, p. xxix.

- Facing Unpleasant Facts, pp. 31, 224.

- "Barcelona and the Spanish civil war". The Observer. 22 July 2012. p. 58.

- Out of the Shadows, a life of Gerda Taro, François Maspero, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-285-63825-9.

- Orwell, George. "Homage to Catalonia". George Orwell.org. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- "Harry Milton – The Man Who Saved Orwell" Archived 24 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine The Hoover Institute. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- Peter Davison (ed.), The Lost Orwell, Timewell Press, 2006. ISBN 1-85725-214-4.

- Davison, Peter (ed.), Orwell in Spain, Penguin Books, 2001, p. 306.

- Shelden, pp. 320–21.

- Daily Worker, 21 May 1938, reproduced in Valentine Cunningham (ed.), Spanish Front: Writers on the Civil War, Oxford, 1986, pp. 304–05.

- Buchanan, Tom. Three Lives of Homage to Catalonia, The Library: Transactions of the Bibliographical Society, 2002, Vol. 3.

- Bowker, Gordon, George Orwell, Chapter 12, "The Road to Morocco. ISBN 978-0-349-11551-1.

- Carr, Raymond, "Orwell and the Spanish war", essay in The World of George Orwell, 1971, ISBN 0-297-00479-4.

- New Statesman, 13 September 1968, letter from G. Flanagan, challenging a review that portrayed Orwell as a liberal.

- American Power and the New Mandarins, p. 117.

- Orwell in Spain, p. 229.

- Hitchens, Christopher, Orwell in Spain, Introduction, p. xviii.

- Dalrymple, William. "Novel explosives of the Cold War". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Alt URL

- Orwell, writing in Time and Tide, review of Red Spanish Notebook, 9 October 1937.

- Orwell in Spain, Introduction xi, xiv.

- Bowker, Orwell, p. 224.

- Foot, Paul, Articles of Resistance, p. 92.

- Bowker, Orwell, p. 226.

- George Orwell, writing in The Observer 24 December 1944.

- James, Clive, Even As We Speak, pp. 11–12.

- Orwell, George. "Looking Back on the Spanish war".

- Carr, Raymond, in Miriam Gross (ed.), The World of George Orwell, p. 71.

- Muggeridge, Malcolm. A Knight of the Woeful Countenance, the World of George Orwell, p.166.

- Bowker, p. 230.

- The World of George Orwell, p.72 Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1971

- Bowker, Orwell, Chapter Eleven, "The Spanish Betrayal", p. 224.

- "The Crystal Spirit" Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine George Orwell Novels. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- Hiebert, Matt. "In Canada and Abroad: The Diverse Publishing Career of George Woodcock". Archived 19 August 2013 at Archive.today Retrieved 19 August 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Homage to Catalonia |

- Homage to Catalonia at Faded Page (Canada)

- Homage to Catalonia – Searchable, indexed etext.

- Homage to Catalonia Complete book with publication data and search option.

- Homage to Catalonia Complete book as plain text.

- Looking back on the Spanish War – an essay written 6 years later.

- BBC Arena Homage to Catalonia on YouTube