Spanish Revolution of 1936

The Spanish Revolution was a workers' social revolution that began during the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 and resulted in the widespread implementation of anarchist and more broadly libertarian socialist organizational principles throughout various portions of the country for two to three years, primarily Catalonia, Aragon, Andalusia, and parts of the Valencian Community. Much of the economy of Spain was put under worker control; in anarchist strongholds like Catalonia, the figure was as high as 75%. Factories were run through worker committees, and agrarian areas became collectivized and run as libertarian socialist communes. Many small businesses like hotels, barber shops, and restaurants were also collectivized and managed by their workers.

| Spanish Revolution | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish Civil War | |

Women training for a militia outside Barcelona, August 1936. | |

| Date | July 19, 1936 |

| Location | Various regions of Spain – primarily Madrid, Catalunya, Aragon, Andalusia, and parts of Levante, Spain. |

| Goals | Elimination of all institutions of state power; worker control of industrial production; implementation of libertarian socialist economy; elimination of social influence from Catholic Church; international spread of revolution to neighboring regions. |

| Methods | Work place collectivization; political assassination |

| Resulted in | Suppressed after ten-month period. |

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

The collectivization effort was primarily orchestrated by the rank-and-file members of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT; National Confederation of Labor) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI; Iberian Anarchist Federation). The socialist Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT; General Union of Workers) also participated in the implementation of collectivization.

History

On July 17, 1936, the military coup began. On July 18, while the military coup leaders continued their uprising, a power vacuum was produced by the collapsed republican state (four governments succeeded each other in a single day) that led to the coercive structures of the state being dissolved or paralyzed in the places where the coup plotters did not seize power. By then, the CNT had approximately 1,577,000 members and the UGT had 1,447,000 members. On July 19 the uprising reached Catalonia, where the workers took up arms, stormed the barracks, erected barricades and eventually defeated the military.

First phase of the revolution (July–September 1936): The summer of anarchy

The CNT and UGT unions called a general strike from July 19 to 23 in response to both the military uprising and the apparent apathy of the State towards it. Despite the fact that there were specific records in previous days of the distribution of weapons among civilian sectors, it was during the General Strike when groups of trade unionists linked to the convening unions and smaller groups, assaulted many of the weapons depots of the state forces, independently of whether they were in revolt against the Government or not.

Already in these first weeks, two nuances were established between the anarcho-syndicalist revolutionary sectors: the radical group, fundamentally linked to the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) and through it to the CNT, which understood the phenomenon in which it participated as a traditional revolution; and the possibilist group, made up of members of a more moderate sector of the CNT, which expressed the convenience of participating in a broader front, the later called Popular Antifascist Front (FPA), the result of adding the unions to the electoral coalition Popular Front.

At the same time, administrative structures were formed outside the State, most of which had a local or regional character, exceeding these limits in specific cases; some of the most important were:

- Central Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia

- Popular Executive Committee of Valencia

- Regional Defense Council of Aragon

- Malaga Public Health Committee

- Gijón War Committee

- Popular Committee of Sama de Langreo

- Santander Defense Council

- Madrid Defense Council

- Council of the Cerdanya

- Antifascist Committee of Ibiza

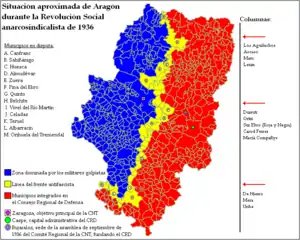

In a few days the fronts of the Spanish Civil War was articulated, of which one of the main fronts in the context of the revolution was that of Aragon. On July 24, 1936, the first voluntary militia left Barcelona in the direction of Aragon. It was the Durruti Column, of around 3,000 people, mostly workers coordinated by Buenaventura Durruti, who first implemented libertarian communism in the municipalities through which they passed. In addition, other popular military structures were formed, such as the Iron Column or the Red and Black Column that also departed for Aragon. All this movement gave rise to an extraordinary concentration of anarchists in the part not taken by the raised military. The arrival, on the one hand, of the thousands of anarchist militiamen from Catalunya and Valencia and the existence, on the other, of a large rural Aragonese popular base allowed the progressive development of the largest collectivist experiment of the revolution.

During this first phase most of the Spanish economy was brought under the control of workers organized by the unions; mainly in anarchist areas such as Catalunya, this phenomenon extended to 75% of the total industry, but in the areas of socialist influence, the rate wasn't so high. The factories were organized by workers' committees, the agricultural areas became collectivized and functioned as libertarian communes. Even places like hotels, hairdressers, means of transport and restaurants were collectivized and managed by their own workers.[1]

The British author George Orwell, best known for his anti-authoritarian works Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, was a soldier in the Lenin Division of the CNT-allied Partido Obrero Unificación Marxista (POUM; Workers' Party of Marxist Unification). Orwell meticulously documented his first-hand observations of the civil war, and expressed admiration for the social revolution in his book Homage to Catalonia.[2]

I had dropped more or less by chance into the only community of any size in Western Europe where political consciousness and disbelief in capitalism were more normal than their opposites. Up here in Aragon one was among tens of thousands of people, mainly though not entirely of working-class origin, all living at the same level and mingling on terms of equality. In theory it was perfect equality, and even in practice it was not far from it. There is a sense in which it would be true to say that one was experiencing a foretaste of Socialism, by which I mean that the prevailing mental atmosphere was that of Socialism. Many of the normal motives of civilized life – snobbishness, money-grubbing, fear of the boss, etc. — had simply ceased to exist. The ordinary class-division of society had disappeared to an extent that is almost unthinkable in the money – tainted air of England; there was no one there except the peasants and ourselves, and no one owned anyone else as his master.

— George Orwell[3]

The communes were operated according to the basic principle of "From each according to their ability, to each according to their need." In some places, money was totally eliminated, replaced by vouchers. Under this system, the cost of goods was often a little more than a quarter of the previous cost. During the revolution, 70% of rural areas were expropriated in Catalunya, about 70% in Eastern Aragon, 91% in the republican sector of Extremadura, 58% in Castilla-La Mancha, 53% in republican Andalusia, 25% in Madrid, 24% in Murcia[4] and 13% in the Valencian Community. 54% of the expropriated area of republican Spain was collectivized, according to IRA data.[5] The provinces where rural communes became most important were those of Ciudad Real -where 1,002,615 hectares (98.9% of cultivated lands) were collectivized in 1938 – and Jaén – where 685,000 hectares (76.3% of cultivated lands) were collectivized, leaving the rest of the republican provinces far behind.[6] Many communes held out until the end of the war. Anarchist communes also produced at a more efficient rate than before being collectivized,[7] with productivity increasing by 20%.[8] The newly liberated zones worked on entirely libertarian principles; decisions were made through councils of ordinary citizens without any bureaucracy.

In Aragon, where libertarian communism was proclaimed as the columns of libertarian militias passed, approximately 450 rural communes were formed, practically all of them in the hands of the CNT, with around 20 led by the UGT .

In the Valencian area, 353 communes were established, 264 led by the CNT, 69 by the UGT and 20 in a mixed CNT-UGT manner. One of its main developments will be the Unified Levantine Council for Agricultural Export (Catalan: Consell Llevantí Unificat d'Exportació Agrícola, CLUEA) and the total socialization of the industries and services of the city of Alcoy.[9]

In Catalan industry, the CNT workers' unions took over numerous textile factories, organized the trams and buses in Barcelona, established collective enterprises in fishing, in the footwear industry and even extended to small retail stores and public shows. In a few days 70% of industrial and commercial companies in Catalunya – which concentrated, by itself, two-thirds of the industry in Spain- had become the property of the workers.

Alongside the economic revolution, there was a spirit of cultural and moral revolution: the libertarian athenaeums became meeting places and authentic cultural centers of theoretical education, in which they organized: literacy classes, talks on health, excursions to the countryside, public access libraries, theatrical performances, political gatherings, sewing workshops, etc. Numerous rationalist schools were founded, which expanded the existing offer of athenaeums and union centers, in which the educational postulates of Francesc Ferrer i Guardia, Ricardo Mella, Leo Tolstoy and Maria Montessori were carried out. Similarly, in the social field, some traditions were considered as types of oppression, and bourgeois morality was also seen as dehumanizing and individualistic. Anarchist principles defended the conscious freedom of the individual and the natural duty of solidarity among human beings as an innate tool for the progress of societies. Thus, for example, during the revolution, women achieved the right to abortion in Catalunya, the idea of consensual free love became popular and there was a rise in naturism.

The social effects of the revolution were less drastic than the economic ones however; while there were some social changes in larger urban areas (Barcelona emphasised a "proletarian style" and Catalonia set up inexpensive abortion facilities), the attitudes of the lower classes remained fairly conservative and there was comparatively little emulation of Russian-style "revolutionary morality".[10]

Public order also varied substantially, getting to do without the classic public order forces (Police, Civil Guard, Courts and army) supplanted by the Control Patrols made up of volunteers, the popular militias and the neighborhood assemblies that were intended to resolve problems that arose. The doors of many prisons were opened, freeing the prisoners among whom there were many politicians but also common criminals, some prisons being demolished.

The anti-fascist, Carlo Rosselli, who before Mussolini's accession to power was Professor of Economics in the University of Genoa, put his judgment into the following words:

In three months Catalonia has been able to set up a new social order on the ruins of an ancient system. This is chiefly due to the Anarchists, who have revealed a quite remarkable sense of proportion, realistic understanding, and organising ability...all the revolutionary forces of Catalonia have united in a program of Syndicalist-Socialist character: socialisation of large industry; recognition of the small proprietor, workers' control...Anarcho-Syndicalism, hitherto so despised, has revealed itself as a great constructive force...I am not an Anarchist, but I regard it as my duty to express here my opinion of the Anarchists of Catalonia, who have all too often been represented to the world as a destructive, if not criminal, element. I was with them at the front, in the trenches, and I have learnt to admire them. The Catalan Anarchists belong to the advance guard of the coming revolution. A new world was born with them, and it is a joy to serve that world.

— Carlo Rosselli[11]

But despite the de-facto decomposition of state power, on August 2 the government took one of the first measures to regain control against the revolution, with the creation of the Volunteer Battalions, the embryo of the Spanish Republican Army. It also promulgated some symbolic decrees, overwhelmed by the revolutionary phenomenon:

- July 18: Decree declaring the military who participated in the coup to be unemployed.

- July 25: Decree declaring government employees who sympathize with the coup plotters to be unemployed.

- July 25: Decree of intervention in industry.

- August 3: Decree of seizure of the railways.

- August 3: Decree of intervention in the sale prices of food and clothing.

- August 8: Decree of seizure of rustic properties.

- August 13: Decree of closure of religious institutions.

- August 19 (Catalunya): Decree of socialization and unionization of the economy.

- August 23: Decree of the creation of the People's Courts.

The first tensions also arise between the strategy of the anarchists and the policy of the Communist Party of Spain and its extension in Catalunya, the PSUC, and on August 6 members of the PSUC left the Catalan autonomous government because of anarcho-syndicalist pressures.

Second phase of the Revolution (September–November 1936): First Government of Victory

Both in this stage and in the previous one, the State structures were limited to legislating on a policy of fait accompli by the Revolution, although due to the growth of the military escalation against the rebellious military, the unions began to circumstantially cede control of the columns to the State for the Defense of Madrid from October–November 1936, which was directed by a semi-independent body – the Madrid Defense Council, in which all the Popular Front parties were represented in addition to the anarchists. The beginning of all this progressively greater agreement and rapprochement between the Popular Front parties and the unions was reflected in the formation of Largo Caballero's "first Government of Victory" on September 4.

Among the measures aimed at absorbing or trying to legislate the activity of the revolutionaries are:

- September 17: Decree of seizure of convicts' estates by the People's Courts.

- October 10: Decree creating Emergency Juries.

- October 22 (Catalunya): Decree on collectivisations and workers' control.

Despite this apparent consent to the revolutionaries, it did not actively intervene in the development of the revolution, as its main objective was to promote and strengthen the Army as the foundation stone of the centralized State. In addition to the repeated attempts at the dissolution of the popular War and Defense Committees, they decreed:

- September 16: Decree taking government control of the Rearguard Vigilance Militia.

- September 28: Decree for the voluntary transfer of heads and officers of the popular militias to the Army.

- September 29: Decree of application of the Code of Military Justice to popular militias.

When the war began to drag on, the spirit of the first days of the revolution loosened and friction between the diverse members of the Popular Front began, in part due to the policies of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE), which were established by the foreign ministry of the Stalinist Soviet Union,[12][13] the largest source of foreign aid to the Republic.

The PCE defended the idea that the ongoing Civil War made it necessary to postpone the ongoing social revolution until the republicans won the war. The PCE advocated not to antagonize the middle classes, the grassroots of the republican parties, which could be affected and harmed by the revolution and turn towards the enemy. In the Popular Front government, there were parties such as the Republican Left, Republican Union and the Republican Left of Catalunya, supported by the votes and interests of the middle class (civil servants, liberal professionals, small merchants and landowning peasants).

The anarchists and the POUMistas (left communists) disagreed with this opinion, understanding that the war and revolution were one and the same. They believed that the war was an extension of the class struggle, and that the proletariat had defeated the military precisely because of this revolutionary impulse that they had been carrying for years and not because of defending a bourgeois republic. The nationalists represented precisely the class that these revolutionaries were fighting: the big capitalists, the landowners, the Church, the Civil Guard and the colonial army.

The militias of the parties and groups that were against the position of the Popular Front government were soon found aid cut off, thus they saw their ability to act reduced, as a result of which Republicans slowly began to reverse the recent changes made in most areas. During this period, some revolutionary structures approved new programs that subordinated them to the Government, which gave rise to the dissolution or beginning of absorption, appropriation and intervention of the revolutionary structures by the republican state government. The situation in most Republican-held areas slowly began to revert largely to its prewar conditions.

An exception was the consolidation of the collectivist process in Aragon, where thousands of libertarian militiamen from Valencia and Catalunya arrived, and where, before the start of the Civil War, there was the most important anarcho-syndicalist labor base affiliated with the CNT in all of Spain. The assembly called in Bujaraloz in the final weeks of September 1936 by the Regional Committee of the CNT of Aragon, with delegations of the towns and confederal columns, following the directives proposed on September 15, 1936, in Madrid by the National Plenary of Regional members of the CNT, proposed to all political and union sectors the formation of Regional Defense Councils federatively linked to a National Defense Council which would perform the functions of the central government, and agreed to the creation of the Regional Defense Council of Aragon, which celebrated its first assembly on October 15 of the same year.[14]

Despite this, on September 26 the most radical and anarchist sectors of Catalunya, finally dominated by the possibilists, began a policy of collaboration with the State, integrating themselves into the autonomous government of the Generalitat de Catalunya, reborn in the place of the Central Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia, which self-dissolved on October 1. On the other hand, on October 6 the Regional Defense Council of Aragon was legalized and regulated by decree. The proposed National Defense Council was regulated, aborting its development. Faced with this apparent tolerance, on October 9 a decree by the Generalitat outlawed all local Committees in Catalunya, formally replacing them with the Municipal Councils of the FPA. All these concessions to the institutions were considered by some as a betrayal of the classical principles of anarchism, which received harsh criticism from colleagues.[lower-alpha 1]

Third phase of the Revolution (November 1936 – January 1937): Second Government of Victory

On November 2, the Popular Executive Committee of Valencia approved a new action program that subordinated it to the policy of Largo Caballero's Republican Government, which included the CNT members Juan García Oliver, Juan López Sánchez, Federica Montseny and Juan Peiró. During this month, the Iron Column decided to briefly take Valencia, in protest at the shortage of supplies provided by the Popular Executive Committee, subsequently leading to clashes in the streets of the city between libertarian militias and communist groups, leaving more than 30 dead.

On November 14, the Durruti Column arrived in Madrid, after giving in to the pressure of the possibilists, who demand collaboration with the State. On November 20, Buenaventura Durruti died in suspicious circumstances fighting in the battle of Madrid, when he had arrived with more than a thousand militiamen from the Front of Aragon.

On December 17, the Moscow daily Pravda published an editorial that reads: "The purge of Trotskyists and anarcho-syndicalists has already begun in Catalonia; it has been carried out with the same energy as in the Soviet Union."[16] The Stalinists had already begun the liquidation of any anti-fascists, collectivizations and other revolutionary structures that did not submit to the directives of Moscow.

On December 23, the Gijón War Committee was transformed by decree into the Interprovincial Council of Asturias and León, regulated by the Republican government authorities and more moderate in its policies, at the same time as it officially recognized the formation of the National Defense Committee. On January 8, 1937, the Popular Executive Committee of Valencia was dissolved.

During this stage, the Government definitively controlled the anarchist popular militias, dissolving them so that they were compulsorily integrated into the Spanish Republican Army, hierarchically structured under the command of professional officers.

The end of the revolution (January 1937 – May 1937)

On February 27, 1937, the government banned the FAI's newspaper Nosotros, thus initiating the period during which most of the publications critical of the government began to suffer censorship. The next day it prohibited the police from belonging to political parties or unions, a measure adopted by the Catalan regional government on March 2. On the March 12, the Generalitat approved an order demanding the seizure of all weapons and explosive materials from non-militarized groups. More confrontations began between the sectors of the FPA, and on March 27 the anarchist advisers of the Catalan autonomous government resigned. During the month of March, the "militarization" of the militias was completed, transformed into a regular Army and subject to its disciplinary and hierarchal regimes, against which many anarchist voices rose up.

On April 17, the day after the ministers of the CNT returned to the Generalitat, a force of Carabineros in Puigcerdá demanded the CNT workers' patrols hand over control of customs on the border with France. Simultaneously, the Civil Guard and Assault Guard were sent to Figueras and other towns throughout the province of Girona to remove control of the workers' organizations from the police, dissolving the autonomous "Council of Cerdanya". Simultaneously, in Barcelona, the Assault Guard proceeded to disarm the workers in public view, in the streets.

During May 1937 the confrontations between the supporters of the revolution and those opposed to it intensified. On the May 13, after the events of the Barcelona May Days, the two Communist ministers, Jesús Hernández Tomás and Vicente Uribe, proposed to the Government that the National Labor Confederation (CNT) and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) be punished, bringing into practice repression against the latter party. On May 16, Largo Caballero resigned, which was followed by the formation of a socialist government under Juan Negrín but without support from anarchists or revolutionaries.

Fenner Brockway, Secretary of the ILP in England who traveled to Spain after the May events in Catalonia (1937), expressed his impressions in the following words:

"I was impressed by the strength of the C.N.T. It was unnecessary to tell me that it was the largest and most vital of the working-class organisations in Spain. The large industries were clearly, in the main, in the hands of the C.N.T.--railways, road transport, shipping, engineering, textiles, electricity, building, agriculture. At Valencia the U.G.T. had a larger share of control than at Barcelona, but generally speaking the mass of manual workers belonged to the C.N.T. The U.G.T. membership was more of the type of the 'white-collar' worker...I was immensely impressed by the constructive revolutionary work which is being done by the C.N.T. Their achievement of workers' control in industry is an inspiration. One could take the example of the railways or engineering or textiles...There are still some Britishers and Americans who regard the Anarchists of Spain as impossible, undisciplined, uncontrollable. This is poles away from the truth. The Anarchists of Spain, through the C.N.T., are doing one of the biggest constructive jobs ever done by the working class. At the front they are fighting Fascism. Behind the front they are actually constructing the new Workers' Society. They see that the war against Fascism and the carrying through of the Social Revolution are inseparable. Those who have seen and understand what they are doing must honour them and be grateful to them. They are resisting Fascism. They are at the same time creating the New Workers' Order which is the only alternative to Fascism. That is surely the biggest things now being done by the workers in any part of the world." And in another place: "The great solidarity that existed amongst the Anarchists was due to each individual relying on his own strength and not depending on leadership. The organisations must, to be successful, be combined with a free-thinking people; not a mass, but free individuals."

— Fenner Brockway[17]

Related subsequent events

On the May 25, the FAI was excluded from the People's Courts. On June 8, 1937, the government issued a decree by which it temporarily outlawed rural communes that had not yet been dissolved. On June 14, a new government of the Generalitat was formed, also without the anarchists and revolutionaries. On June 15, the POUM was outlawed and its executive committee was arrested. On the June 16 the 29th Division (formerly the POUM's Lenin Division) was dissolved.

In August 1937, criticism of the USSR was prohibited by means of a government circular. In this month, the central government also ordered the dissolution of the Aragón Defense Council, practically the last remaining body of revolutionary power, which was militarily occupied by Republican Army troops on August 10. Joaquín Ascaso, its president, was arrested. Likewise, the eleventh communist division attacked various committees of the Aragonese people and dissolved collective agricultural production, which soon after was reorganized. On September 7, the government reauthorized religious worship in private, one of its many measures trying to reestablish the power of the Government in the republican zone, while in Barcelona there were demonstrations against the dissolution of the anarcho-syndicalist publication "Solidaridad Obrera". On September 16, political rallies were prohibited in Barcelona. On the September 26, the Asturian Council proclaimed itself the Sovereign Council of Asturias and León, independent from the Spanish Republic.

On October 21, a demonstration by anarchist and socialist militants took place in front of the San Miguel de los Reyes prison in Valencia, threatening to break down the doors if the prisoners were not freed. On November 12, the CNT withdrew from the FPA committees.

On January 6, 1938, the Government published a decree prohibiting all new issuance of banknotes and coins by committees, municipalities, corporations, etc. and a period of one month was given for them to be withdrawn from circulation, trying to end the last remnants of the Revolution.

During that year many of the large landowners returned and demanded the return of their property. Collectivization was progressively annulled despite the great popular opposition that it involved.

Sam Dolgoff estimated that about eight million people participated directly or at least indirectly in the Spanish Revolution, which he claimed "came closer to realizing the ideal of the free stateless society on a vast scale than any other revolution in history:"[18]

In Spain during almost three years, despite a civil war that took a million lives, despite the opposition of the political parties (republicans, left and right Catalan separatists, socialists, Communists, Basque and Valencian regionalists, petty bourgeoisie, etc.), this idea of libertarian communism was put into effect. Very quickly more than 60% of the land was collectively cultivated by the peasants themselves, without landlords, without bosses, and without instituting capitalist competition to spur production. In almost all the industries, factories, mills, workshops, transportation services, public services, and utilities, the rank and file workers, their revolutionary committees, and their syndicates reorganized and administered production, distribution, and public services without capitalists, high salaried managers, or the authority of the state.

The various agrarian and industrial collectives immediately instituted economic equality in accordance with the essential principle of communism, 'From each according to his ability and to each according to his needs.' They coordinated their efforts through free association in whole regions, created new wealth, increased production (especially in agriculture), built more schools, and bettered public services. They instituted not bourgeois formal democracy but genuine grass roots functional libertarian democracy, where each individual participated directly in the revolutionary reorganization of social life. They replaced the war between men, 'survival of the fittest,' by the universal practice of mutual aid, and replaced rivalry by the principle of solidarity....

This experience, in which about eight million people directly or indirectly participated, opened a new way of life to those who sought an alternative to anti-social capitalism on the one hand, and totalitarian state bogus socialism on the other.

— Gaston Leval[19]

Social revolution

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

|

Economic

The most notable aspect of the social revolution was the establishment of a libertarian socialist economy based on coordination through decentralized and horizontal federations of participatory industrial collectives and agrarian communes. Andrea Oltmares, professor in the University of Geneva, in the course of an address of some length, said:

"In the midst of the civil war the Anarchists have proved themselves to be political organizers of the first rank. They kindled in everyone the required sense of responsibility, and knew how, by eloquent appeals, to keep alive the spirit of sacrifice for the general welfare of the people. "As a Social Democrat I speak here with inner joy and sincere admiration of my experiences in Catalonia. The anti-capitalist transformation took place here without their having to resort to a dictatorship. The members of the syndicates are their own masters and carry on the production and the distribution of the products of labor under their own management, with the advice of technical experts in whom they have confidence. The enthusiasm of the workers is so great that they scorn any personal advantage and are concerned only for the welfare of all."

— Andrea Oltmares[20]

The key developments of the revolution were those related to the ownership and development of the economy in all its phases: management, production and distribution. This was accomplished through widespread expropriation and collectivization of privately owned productive resources (and some smaller structures), in adherence to the anarchist belief that private property is authoritarian in nature.

The economic changes that followed the military insurrection were no less dramatic than the political. In those provinces where the revolt had failed the workers of the two trade union federations, the Socialist UGT and the Anarchosyndicalist CNT, took into their hands a vast portion of the economy. Landed properties were seized; some were collectivized, others were distributed among the peasants, and notarial archives as well as registers of property were burnt in countless towns and villages. Railways, tramcars and buses, taxicabs and shipping, electric light and power companies, gasworks and waterworks, engineering and automobile assembly plants, mines and cement works, textile mills and paper factories, electrical and chemical concerns, glass bottle factories and perfumeries, food-processing plants and breweries, as well as a host of other enterprises, were confiscated or controlled by workmen's committees, either term possessing for the owners almost equal significance in practice. Motion-picture theatres and legitimate theatres, newspapers and printing shops, department stores and bars, were likewise sequestered or controlled as were the headquarters of business and professional associations and thousands of dwellings owned by the upper class.

— Burnett Bolloten[21]

Numerous experiences of management and control of workers and agrarian collectivizations were carried out throughout the Republican territory. In some towns and cities, the transformations were spontaneous and took different paths, however in a large number of cases the first step was taken in Barcelona and in the rest of Spain it was imitated.

The socialized industry

After the coup d'état and the beginning of the civil war, many owners in the republican zone were assassinated, imprisoned or exiled, thus leaving a multitude of companies and factories without direction.[22] This situation led to the takeover of factories, companies and entire industries by the unions.[23] Within the industrial sphere the revolution was carried out in different ways. These differences radiated from numerous factors: the disappearance of the owner, the strength and political orientation of the workers' organizations, the existence of foreign capital in the company itself or even the destination of its products. Faced with this situation, there were three major orientations:[24]

- Workers' control occurred where the existence of foreign capital limited the revolutionary capacity of the workers

- Nationalization occurred in companies with management sympathetic to Soviet communism, and later in all war industries

- Socialization occurred in those industries that did not have a large volume of foreign capital and the political affiliation approached or defended the postulates of the CNT-FAI.

At the beginning of the war, Catalunya held around 70% of all the industry in Spain,[25] which, as the nerve center of the CNT and Spanish anarchism, gave it a great importance within the revolutionary process, being one of the places where some of the most radical revolutionary experiments took place.[26] In all the places where measures were carried out in the industry, it is necessary to look at certain factors, such as the type of industry or the implantation of the different workers' organizations and political parties, especially at the beginning of the revolution, when the actions were more broad, they had greater freedom of movement and the state had no capacity to oppose it.[27]

Socialization

This measure consisted of the management of the industry by the workers themselves. On the practical level, it resulted in the abolition of private property by collective management and property, based on the principles of direct action and anti-authoritarianism of anarchism.[28] In this case the Management fell to a board of directors made up of less than fifteen people in which all the productive and service levels of the company were involved and in which the trade union centrals had to be proportionally represented. This council was elected in a workers' assembly to which they were responsible.[29] The benefits were distributed among: workers, company and social purposes. Within the company as a reserve fund, among the workers as an amount before which the assembly decided its use and for social purposes such as contributions to regional credit unions, the unemployed or investments in education and health.[30][31][32]

Nationalization

This measure consisted of the management of the industry by the state. It resulted in the abolition of private property by state management and ownership.[33] The boards of directors were controlled by the state and the benefits were reduced to the state and the company itself. It was the choice that the Communist Party defended, since in this way it could weaken the economic power that the CNT held.[34]

Worker Control

This measure consisted of the creation of a Workers' Committee that would be in charge of controlling working conditions, the cash movements of the companies and the control of production in all those companies in which the property remained private,[35] excepting only those that did not gather enough personnel to meet the conditions to belong to the committee. These committees were made up of between three and nine members, they were made up of representatives of the two unions in a proportional manner and trying to represent all the services or industries that the company dealt with. These representatives were elected in an assembly of the center, an assembly in which it was decided whether the committee also had the right to sign the movements of funds, the frequency of meetings between the committee and the patron, and the frequency of meetings between them. The positions were not remunerated, they lasted two years and were re-eligible and were responsible for their management to the assembly of the company and to the General Council of Industry. The committee approved the hours, salary increases and decreases, changes of categories or workplace and notifications of absences to workers. The committee had to meet once a week to discuss the employer's proposals and to ensure compliance with the official provisions. The employer representation was still in the power of the legal representation of the company, the power to contract, the custody of the box and the signature and the fixing of their remuneration. If the company had a corporation or other commercial model as a legal entity, a member of the committee had to attend the council meetings with voice but without vote.[36]

Salary

The remuneration of work was one of the points of friction between the anarchist and Marxist views during the revolutionary stage. While the anarchist organizations defended a single family salary, the Marxist organizations defended a staggered salary according to the type of work that was carried out.[37] These differences would be motivated by the conceptions that these two views of the individual have and by the motivation of the individual as a producer. In the first place, while anarchism understands the individual as a subject with needs that must be covered, Marxism understands the individual as a producer.[38] The second place, anarchism defends that the worker will strive to produce and improve the process while controlling the productive activity, Marxism on the other hand understands that the worker will try harder in exchange for receiving a higher remuneration.[39]

Film industry

The CNT's Entertainment Union was a model of organization and operation in the confederal media. It was significant that the cinemas and theaters of Barcelona were one of the first and most resounding occupations of the activists from Barcelona's CNT between July 20 and 25. On July 26 a "Technical Commission" was appointed in charge of preparing a project that defined the new framework of work in cinemas and theaters. That same day, the Catalan Generalitat, overwhelmed by events, created the "Comisaría d'Espectacles de Catalunya" which did not work in practice, the production of workers organized through the CNT union completely took over production.

The revolutionary enthusiasm organized and energized all the cinematographic and theatrical activities in Barcelona from August 6 to May 1937. The project began by standardizing wages for all job types in the branches of the film industry. Sickness, disability, old age and forced unemployment benefits were established permanently. This whole system employed about 6,000 people and supported 114 cinemas, 12 theaters and 10 music halls during that period. An opera company was even created at the Tivoli theater, in an attempt to bring the genre closer to the general public.

It can be said that it was one of the sectors that functioned the best economically, even building some cinemas such as the "Ascaso" (today "Vergara"). Others were reformed or finished building such as the "Durruti" cinema (now "Arenas" cinema).

At the political level, the collectivization of cinema was a new way of understanding art radically opposed to the bourgeois and capitalist system. There was no unity of criteria in the creative process, dogmatism was not installed behind the scenes or behind the lens, and the "seventh art" incorporated a new form of journalism by taking cameras out into the street to shoot what was happening around them. The popular mobilization had been launched to tell what their gaze saw and the messages emerged as counter-information. The information of the people thus replaced that of power.

Between 1936 and 1937, more than a hundred films were produced promoted by the production company and the distributor created by the CNT. The documentary genre was undoubtedly the most accomplished as the framework of the war inevitably flooded any activity. The SIE Films (Syndicate of the Entertainment Industry) and the Spartacus Films brand were created for the production of films. The Union had two large studios with three plateaux for filming, and the Palace of Belgium was set up on the premises of Montjuïc, for auxiliary services of sets and extras. However, the repression of May 1937 strangled the Social Revolution in the streets of Barcelona and, although films continued to be made, the previous production rate slowed considerably.

Anarchist film production was a large part of the creative life in Catalunya at the time and it spread to Aragon, Madrid and Levante through different models, probably adapting to the circumstances of towns and cities and the working people who made them possible. Although productive activity in Madrid was less important than in Barcelona, 24 films were shot, between documentaries and fiction.

Wood Industry

Between 7,000 and 10,000 people worked in this industry, or industrial branch, during the Civil War. Shortly after the general strike, when workers returned to their companies and workshops, the woodworkers began to socialize their industrial sector.[40] They began by seizing the companies, and through a general plan to rationalize efforts and resources, they closed the workshops that did not meet sufficient health and safety conditions, regrouping them to have large and clear premises. Although at the beginning there were still small workshops, later they were also added to the socialization.

After a few months of spontaneity, efforts were coordinated until the 8-hour day, the unification of wages, the improvement of working conditions and the increase of production were achieved. Socialization went through all the phases of production: sawmill, joinery and carpentry.[41]

A professional school and libraries were created, there was even a Socialized Furniture Fair in 1937. They managed to coordinate with the socialized wood industry of the Levante, to manufacture different types of furniture and not compete. Although some exchanges are carried out through barter (with other socialized branches, or with some agrarian communities), in most cases they had to use money.

The agrarian communities

The trend of latifundismo in the Spanish countryside led to widespread unrest among the peasantry. The confiscations of the 19th century had failed to substantially modify the structure of land ownership and the republic's agrarian reform process had not fulfilled the expectations of change. Thus, as a result of the coup d'état, a revolutionary process began in which the peasants expropriated the landowners and organized self-managed communities based on collective ownership of the means of production. This phenomenon has been called "collectivization." The collectivities were created through different means. In regions that the nationalists had not seized, the municipalities and the peasants themselves initiated collectivization.

These collectivities formed a collective labor regime in which the lands of the aristocrats and landowners were expropriated and joined together with the lands of other collectivists. Animals, tools and work were all held and done collectively. Periodic assemblies were held to direct what the community was doing, as well as negotiate with other communities and encourage exchange. Most of these collectivities were born in response to the lands that were left empty or were seized by committees after the coup d'état.[42] The IRA counted between 1,500 and 2,500 communities throughout Spain.[43] These collectivities came to be territorially organized as was the case in Aragon, in Castile with the unification of the peasant federations,[44] or in Levante with the creation of the CLUEA.[45] Throughout the war they were present in the political and economic approaches of each formation, being in a way another of the ideological battlefields within the Republican side.[46]

The union or departure from the community was free. If a small owner wanted to continue working the land on their own, they could do so as long as they did not hire anyone.[47] That is, the collectivities were organizations within the people themselves that managed the production, work and distribution of all goods and services. In some towns they became the entire population while in others they were only part of it.[48] The UGT-organized National Federation of Land Workers (FNTT), which had more than half a million affiliates, was largely in favor of the collectivities.[49]

In Barcelona the communities exercised a management role similar to the cooperatives, without employers, as everything was controlled by their own workers. City services such as urban transport were managed by communities. In the countryside of Aragon, the Valencian Community and Murcia, the agrarian communities acted as communes. The business role was joined by that of an institution that replaced the local powers of the municipalities in which they were created, in many cases abolishing money and private property (one of the principles of socialist anarchist society). Some of the most significant Aragonese communities were those of Alcañiz, Alcorisa, Barbastro, Calanda, Fraga, Monzón or Valderrobres. In mid-February 1937, a congress was held in Caspe, the purpose of which was to create a federation of collectives attended by 500 delegates representing 80,000 Aragonese collectivists. Along the Aragon front, the Anarchist-influenced Council of Aragon, chaired by Joaquín Ascaso, had assumed control of the area. Both the Council of Aragon and these communities were not well regarded by the government of the Republic, so on August 4 the Minister of National Defense, Indalecio Prieto, issued orders to the Army and the 11th Division of Commander Enrique Líster was sent of "maneuvers" to Aragon, dissolving the Council of Aragon on August 11.

In Aragon, agrarian collectives were formed that were structured by working groups of between five and ten members. To each work group, the community assigned a piece of land for which it was responsible. Each group elected a delegate who represented their views at community meetings. A management committee was responsible for the day-to-day running of the community. This committee was in charge of obtaining materials, carrying out exchanges with other areas, organizing the distribution of production and the public works that were necessary. Its members were elected in general assemblies in which all the people who made up the community participated.

In many villages and towns money was even abolished and replaced by vouchers signed or stamped by committees. Although some communities had problems with the republican authorities (the 11th Division of Líster entered Aragon to dissolve them in August 1937), others, such as those of Castilla, Region of Murcia or Andalusia, could function with more or less success until 1939, when they were dissolved by Franco's troops.

Decision making

Following libertarian practices, the collectivities were governed by a structure that can be defined as "from the bottom up." That is, all decisions and appointments were made in assembly,[50][51][52] where all the people who wanted from the population participated.[53] In these assemblies all issues concerning the people were discussed, and people who had decided not to join the community, without vote in that case. In these same assemblies the progress of the community and the actions to be taken were debated.

Federalism

On a broader organizational level, the communities aspired to organize themselves into federations following the example of Aragon. There were congresses in favor of the creation of federations of collectivities but in no case was a more elaborate body than in Aragon ever constituted. There were other cases of federalism, such as CLUEA, the managing body for citrus exports in the Levante.

Among the collectivities there was also exchange, either in the form of barter, with their own paper money or with official money.

Environmentalism

The Spanish Revolution undertook several environmental reforms which were possibly the largest in the world at the time. Daniel Guerin notes that anarchist territories would diversify crops, extend irrigation, initiate reforestation and start tree nurseries.[54] Once there was a link discovered between air pollution and tuberculosis, the CNT shut down several metal factories.[55]

Economy

The collectives were formed in the villages as a result of the abandonment, expropriation or accumulation of land and work tools by the peasants. They were made up of people who wanted to belong and the work to be done was divided among the different members. In places where money was not abolished, the salary became in most cases a family salary. According to this salary, it was charged according to the members of the family, increasing according to whether they were a couple or had children.[56][57]

Money

The economic policies of the anarchist collectives were primarily operated according to the basic communist principle of "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need". One of the most outstanding aspects of the communities was the approaches with which they faced the problem of money and the distribution of products. In the villages and towns where money was abolished, different solutions were sought, these ideas varied according to locality and town: vouchers signed or stamped by committees, account books, local coins, ration tables or individual or family checkbooks.[58] In the cases where money was abolished, it was used to acquire products or tools that the community could not obtain by itself.

In many communities money for internal use was abolished, because, in the opinion of Anarchists, "money and power are diabolical philtres, which turn a man into a wolf, into a rabid enemy, instead of into a brother." "Here in Fraga [a small town in Aragon], you can throw banknotes into the street," ran an article in a Libertarian paper, "and no one will take any notice. Rockefeller, if you were to come to Fraga with your entire bank account you would not be able to buy a cup of coffee. Money, your God and your servant, has been abolished here, and the people are happy." In those Libertarian communities where money was suppressed, wages were paid in coupons, the scale being determined by the size of the family. Locally produced goods, if abundant, such as bread, wine, and olive oil, were distributed freely, while other articles could be obtained by means of coupons at the communal depot. Surplus goods were exchanged with other Anarchist towns and villages, money being used only for transactions with those communities that had not adopted the new system.

— Burnett Bolloten[59]

Obstacles

The biggest problems that the communities faced were those derived from the war itself: shortage of raw materials such as fertilizers, seeds, gear and tools or the lack of labor due to the mobilization. They also had great problems in their relationship with the state, as the collectivities were an expression of power outside the state and also as ideological rivals of the communism that dominated the government. This is how they suffered discrimination in the financing of the IRA, the CLUEA's competition in the Levante,[60] forced unionization in Catalunya[61] or their forced dissolution in Aragon.[62]

Status Response

Once the state was restructured at any of its levels, it tried to stop, direct or at least channel any revolutionary organism. Regarding the collectivities, the Minister of Agriculture Uribe drew up a decree of agrarian collectivizations that only sought to channel them, with this decree an excessive importance was given to the individual farmer.[63]

The scope of the revolution

The figures are often fuzzy. Various quantities have been handled. Gastón Leval says that there were 3 million people who participated. Vernon Richards, talks about 1,500,000. Frank Mintz in a 1970 study says it was between 2,440,000 and 3,200,000. But in 1977 he already revised these figures, placing it at a minimum of 1,838,000 collectivists. Its justification is the following:

Andalusia. The minimum number of agricultural communities is 120 and the maximum of 300, taking an average of 210 with 300 people in each, would be 63,000 people.

Aragon. The figure of 450 communities with 300,000 inhabitants is acceptable. In addition, the UGT had a certain strength, for example 31 communities in Huesca.

Cantabria. The data cited, although minimal, can be noted: a hundred agricultural groups with 13,000 people.

Catalonia. The minimum data for agricultural communities is 297 and the maximum is 400. If we take 350 with 200 people on average, we have 70,000. Taking 80% of the 700,000 workers in the province, we have 560,000 people, that is, with their families, a minimum of 1,020,000.

Center. CNT agricultural collectives with 23,000 families, that is, a minimum of 67,992 people, approximately, to which must be added the UGT collectives, of at least as much, this is 176,000 in agriculture. There were many industrial collectives in the capitals and in the towns. It seems logical to me to consider a minimum of 30,000 people affected.

Extremadura. The figure of 30 groups with an average of 220 people, that is, 6,000 people, should be considered as a maximum for the CNT and the UGT.

Raise. Our estimate is at least 503 groups in agriculture, which would affect 130,000 people. In the industry, the minimum and hypothetical figure is 30,000, which as in the case of the Center is reasonable.

Total. 758,000 collectivists in agriculture and 1,080,000 in industry. We therefore have 1,838,000, a minimum figure as explained at the beginning.— Frank Mintz. "Self-management in revolutionary Spain". La Piqueta, 1977.[64]

The revolution in education

Within the educational field there were also important experiences, although, as will be seen, these experiences had great drawbacks to carry out a more intense work. One of the most significant changes was due to the fact that education went from being a defensive and destructive field of capitalism to being understood as a fundamental pillar of the construction of the new revolutionary society.[65]

Primary and secondary education

The New Unified School Council (UNSC), created in Catalonia on July 27, 1936, was entrusted with the task of restructuring the educational system in Catalonia. This organization could be understood as a model of public management of education: free, co-educational, secular, use of the mother tongue and unification of the different educational levels.[66] However, the CENU also raised suspicions within the Catalan confederal militancy and a Regional Federation of Rationalist Schools was created outside the organization. However, its influence in neighboring regions is evident.[67]

In rural areas, the collectivist movement was forced to intervene more directly than in the cities.[68] That is why either because there were no educational structures before or because there were greater autonomy, in many rural municipalities the community faced local, professional or municipal expenses.[69] It was also important to stop at the statutes of some communities that prohibited child labor.[70]

Vocational and technical training

Within the field of vocational and technical training, various initiatives were created and developed. In the industrial field, these were largely the result of the unions, which, knowing that they were lacking in technicians and distrusting them, tried to train members of their organizations. Among these initiatives were numerous schools of particular trades: railways, optics, transporters or metallurgists or departments dedicated to professional training.[71]

In the agricultural field, federations of trade unions carried out this type of initiative, among which we can find the school of secretaries of Levante, the agricultural university of Moncada, the regional institute of agriculture and livestock or the school of militants of Monzón.[72]

Non-Formal and Cultural Education

Within non-formal education there were the libertarian athenaeums or popular, social centers in which different informative, cultural or work tasks were developed. The athenaeums had a very strong tradition where anarchism had strength, however in the war they even expanded into areas with little CNT roots. In some cases such as Madrid, these athenaeums came to create schools, have health insurance and promote another type of service.[73]

Various communities also carried out other initiatives such as the creation of libraries, artistic activities, a cinema forum,[74] the creation of theater groups, athenaeums,[75] the foundation of its own academies,[76] or nursery schools.[77]

Problems faced

The problems that had to be faced had two different roots: on the one hand there were the problems typical of a war situation, to which those that had been dragging the educational sphere can be added, and on the other, those typical of the rationalist school movement.[78]

- In the first place, it is necessary to point out the poor school structure that Spain had.[lower-alpha 2] This problem was exacerbated in rural areas, where a large number of municipalities lacked schools or were in a very precarious situation, with many communities still trying to eradicate child labor.[80]

- In a sense similar to the previous point, one of the problems suffered at a general level and in the rationalist school in particular was the lack of trained teachers. This problem, which is inseparable from the structural lack of education, was aggravated in rural areas when it coincided with the summer vacation period.[81] The lack of trained teachers had a special incidence in the libertarian sphere since most of the people who were in charge of the rationalist schools were militants with interest and good will.[82]

- On another spectrum, one of the problems that was tried to solve was the lack of coordination between rationalist centers. This coordination occurred in most cases informally on the basis of affinity and proximity. The most interesting response in this regard was the Regional Federation of Rationalist Schools of Catalonia, which planned the creation of an editorial and a Rationalist Norm. However, the federation did not have a remarkable evolution.[83]

- And finally, the scarcity of economic and material resources must be pointed out due to the need to maintain a war economy and the economic drowning to which the collectivist movement was subjected. This lack of resources was a fundamental element to understand the lack of reorganization of the educational structure, with problems such as the lack of endowments, which was sometimes made up with the transformation of other buildings.[84]

The revolution, the Civil War and the militias.

The coincidence of the revolution and the Spanish Civil War meant that in the military field various initiatives avre developed coordinated by the new administrations established by the revolutionary wave, most of which will be unsuccessful.

The Aragon front

This was the first military initiative, developed on July 24, 1936, when the first voluntary militia, the Durruti Column, departed from Barcelona in the direction of Zaragoza.[85] One of the last columns was the Los Aguiluchos Column, which left Barcelona on August 28 in the direction of Huesca. The columns of Barcelona and Lleida headed mainly towards Huesca and Zaragoza, and the Valencian ones towards Teruel, repeatedly besieging the three provincial capitals. At the beginning of September the Carod-Ferrer Column arrived and was installed around Villanueva de Huerva.

This operation lasted until the end of September, when faced with the imperative of the imminent Battle of Madrid some of the columns gave up their independence, subordinating themselves to the requirements of the Government.

The Mallorca landings

The idea of an expedition to Mallorca had been present since July 19, when it was taken by the nationalists, along with Ibiza and Formentera. Menorca was the only island in the Balearic archipelago that remained in republican hands. The republicans manage to take back the islands of Ibiza, Formentera and Cabrera, landing on the island of Mallorca in the area of Punta Amer and Porto Cristo. On September 5, Bayo's column began the withdrawal from Mallorca, which lasted until September 12, returning to Barcelona.

The so-called "Mallorca landings" could be considered definitively concluded when on September 20 Francoist troops from Mallorca occupy Formentera.

The defense of Madrid

The last major operation of the confederal militias took place in November 1936. Buenaventura Durruti, one of the main protagonists of the Revolution, died on November 20, 1936. The resistance of the popular militias, together with the reinforcements of the International Brigades, allowed Madrid to resist the attack of the rebels. In the subsequent defense of the city, numerous anarcho-syndicalists intervened, such as the column led by the Madrilenian Cipriano Mera.

Nevertheless, the confederal militias were militarized into the Spanish Republican Army in 1937.

Criticisms

Criticism of the Spanish Revolution has primarily centered around allegations of coercion by anarchist participants (primarily in the rural collectives of Aragon), which critics charge run contrary to libertarian organizational principles. Bolloten claims that CNT–FAI reports overplayed the voluntary nature of collectivization, and ignored the more widespread realities of coercion or outright force as the primary characteristic of anarchist organization.[86]

Although CNT-FAI publications cited numerous cases of peasant proprietors and tenant farmers who had adhered voluntarily to the collective system, there can be no doubt that an incomparably larger number doggedly opposed it or accepted it only under extreme duress...The fact is...that many small owners and tenant farmers were forced to join the collective farms before they had an opportunity to make up their minds freely.

He also emphasizes the generally coercive nature of the war climate and anarchist military organization and presence in many portions of the countryside as being an element in the establishment of collectivization, even if outright force or blatant coercion was not used to bind participants against their will.[87]

Even if the peasant proprietor and tenant farmer were not compelled to adhere to the collective system, there were several factors that made life difficult for recalcitrants; for not only were they prevented from employing hired labor and disposing freely as their crops, as has already been seen, but they were often denied all benefits enjoyed by members...Moreover, the tenant farmer, who had believed himself freed from the payment of rent by the execution or flight of the landowner or of his steward, was often compelled to continue such payment to the village committee. All these factors combined to exert a pressure almost as powerful as the butt of the rifle, and eventually forced the small owners and tenant farmers in many villages to relinquish their land and other possessions to the collective farms.

This charge had previously been made by historian Ronald Fraser in his Blood of Spain: An Oral History of the Spanish Civil War, who commented that direct force was not necessary in the context of an otherwise coercive war climate.[88]

[V]illagers could find themselves under considerable pressure to collectivize – even if for different reasons. There was no need to dragoon them at pistol point: the coercive climate, in which 'fascists' were being shot, was sufficient. 'Spontaneous' and 'forced' collectives existed, as did willing and unwilling collectivists within them. Forced collectivization ran contrary to libertarian ideals. Anything that was forced could not be libertarian. Obligatory collectivization was justified, in some libertarians' eyes, by a reasoning closer to war communism than to libertarian communism: the need to feed the columns at the front.

Anarchist sympathizers counter that the presence of a "coercive climate" was an unavoidable aspect of the war that the anarchists cannot be fairly blamed for, and that the presence of deliberate coercion or direct force was minimal, as evidenced by a generally peaceful mixture of collectivists and individualist dissenters who had opted not to participate in collective organization. The latter sentiment is expressed by historian Antony Beevor in his Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939.[89]

The justification for this operation (whose "very harsh measures" shocked even some Party members) was that since all the collectives had been established by force, Líster was merely liberating the peasants. There had undoubtedly been pressure, and no doubt force was used on some occasions in the fervor after the rising. But the very fact that every village was a mixture of collectivists and individualists shows that the peasants had not been forced into communal farming at the point of a gun.

Historian Graham Kelsey also maintains that the anarchist collectives were primarily maintained through libertarian principles of voluntary association and organization, and that the decision to join and participate was generally based on a rational and balanced choice made after the destabilization and effective absence of capitalism as a powerful factor in the region.[90]

Libertarian communism and agrarian collectivization were not economic terms or social principles enforced upon a hostile population by special teams of urban anarchosyndicalists, but a pattern of existence and a means of rural organization adopted from agricultural experience by rural anarchists and adopted by local committees as the single most sensible alternative to the part-feudal, part-capitalist mode of organization that had just collapsed.

There is also focus placed by pro-anarchist analysts on the many decades of organization and shorter period of CNT–FAI agitation that was to serve as a foundation for high membership levels throughout anarchist Spain, which is often referred to as a basis for the popularity of the anarchist collectives, rather than any presence of force or coercion that allegedly compelled unwilling persons to involuntarily participate.

Michael Seidman has suggested there were other contradictions with workers' self-management during the Spanish Revolution. He points out that the CNT decided both that workers could be sacked for 'laziness or immorality' and also that all workers should 'have a file where the details of their professional and social personalities will be registered.'[91] He also notes that the CNT Justice Minister, García Oliver, initiated the setting up of 'labour camps',[92] and that even the most principled anarchists, the Friends of Durruti, advocated "forced labour".[93] However, Garcia Oliver explained his idealistic vision of justice in Valencia on December 31, 1936; common criminals would find redemption in prison through libraries, sport and theatre. Political prisoners would achieve rehabilitation by building fortifications and strategic roads, bridges and railways, and would get decent wages. Garcia Oliver believed it made more sense for fascist lives to be saved than for them to be sentenced to death. This is in contrast to the policy of mass annihilation of political opponents enacted in the rebel zone during the war.[94]

Anarchist authors have sometimes understated the problems that the working class faced during the Spanish Revolution during the early period of the movement. For example, while Gaston Leval admits that the collectives imposed a 'work discipline' that was 'strict', he then restricts this comment to a mere footnote.[95] Other radical commentators, however, have incorporated the limitations of the Spanish Revolution into their theories of anti-capitalist revolution. Gilles Dauvé, for example, uses the Spanish experience to argue that to transcend capitalism, workers must completely abolish both wage labour and capital rather than just self-manage them.[96]

See also

Notes

References

- Andreassi 1996, p. 86

- Orwell 1938, pp. 4–6

- Orwell 1938, p. 51

- González Martínez 1999, p. 93

- Payne 1970, pp. 241–267

- Garrido González 2006, p. 6

- Sewell 2007, p. 141

- Kelsey 1991

- Quilis Tauriz 1992, pp. 83–85

- Payne 1973

- Rocker 2004, pp. 66–67

- Perarnau, Lluís. "España traicionada Stalin y la Guerra Civil". Fundación Federico Engels. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- Manuel Vera, Juan (November 25, 1999). "Estalinismo y antiestalinismo en España" (in Spanish). Fundación Andreu Nin. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011.

- Peirats 1971, p. 211

- Ferrán Gallego 2008, p. 367

- Enzensberger 2006

- Rocker 2004, pp. 66–67

- Dolgoff 1974, p. 5.

- Dolgoff 1974, p. 6.

- Rocker 2004, pp. 66–67

- Bolloten 1991, p. 1107

- Peirats 1971, p. 275

- Pérez Baró 1974, pp. 45–46

- Thomas 1961, p. 575

- Leval 1975, p. 268

- Castells Duran 1996, p. 11

- Castells Duran 1996, p. 14

- Castells Duran 1996, p. 28

- Pérez Baró 1974, pp. 90–91

- Pérez Baró 1974, p. 93

- Leval 1975, p. 401

- Quilis Tauriz 1992, p. 181

- Castells Duran 1994, p. 30

- Bolloten 1980, p. 309

- Pérez Baró 1974, p. 81

- Pérez Baró 1974, pp. 85–86

- Castells Duran 1994, p. 19

- Castells Duran 1994, p. 22

- Castells Duran 1994, p. 23

- Peirats 1971, p. 170

- Thomas 1961, p. 575

- Casanova 1997, pp. 200

- Thomas 1961, p. 600

- Leval 1975, pp. 231–232

- Quilis Tauriz 1992, pp. 81–85

- Casanova 1997, pp. 200

- Peirats 1971, pp. 271–345

- Quilis Tauriz 1977, p. 175

- Leval 1975, p. 226

- Leval 1975, p. 255

- Zafrón Bayo 1979, p. 51

- Zafrón Bayo 1979, p. 112

- Zafrón Bayo 1979, p. 48

- Guerin 1970, p. 134

- McKay, Iain (January 20, 2009). "Objectivity and Right-Libertarian Scholarship".

- Mintz 2013, p. 139

- Bolloten 1991, p. 66

- Leval 1975, pp. 237–246

- Bolloten 1991, p. 66

- Quilis Tauriz 1992, pp. 83–85

- Mintz 2013, p. 90

- Borrás 1998, pp. 71–73

- Mintz 2013, p. 117

- Mintz 2013, pp. 198–199

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 156

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 183–184

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 191, 202

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 161

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 195, 204

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 161

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 234–240

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 242–256

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 267–271

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 190

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 200–201

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 205

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 211

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 159

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 160

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 160–161

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, p. 162

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 163–165

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 166–167

- Tiana Ferrer 1987, pp. 168–171

- Peirats 1971, p. 161

- Bolloten 1991, p. 74

- Bolloten 1991, p. 75

- Fraser 1979, p. 349

- Beevor 2006, p. 295

- Kelsey 1991, p. 161

- Seidman 1991

- Seidman 1991

- Seidman 1991

- Preston 2012, p. 388, xiv

- Leval 1975, p. 252

- Dauvé, Gilles (2000). When Insurrections Die.

Bibliography

Principle sources

- Andreassi, Alejandro (1996). Libertad también se escribe en minúscula. ISBN 84-88711-23-9.

- Borrás, José (1998). Del Radical-Socialismo al Socialismo Radical y Libertario (in Spanish). Madrid: Fundación Salvador Seguí. ISBN 84-87218-17-2.

- Castells Duran, Antoni (1996). El proceso estatizador en la experiencia colectivista catalana (1936-1939) (in Spanish). Madrid: Nossa y Jara. ISBN 84-87169-83-X.

- Casanova, Julián (1997). De la calle al frente. El anarcosindicalismo en España. (1936-1939) (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica. ISBN 84-7423-836-6.

- Bolloten, Burnett (1980). La revolución española. Sus orígenes, la izquierda y la lucha por el poder durante la guerra civil 1936-1937 (in Spanish). Barcelona: Grijalbo. ISBN 84-253-1193-4.

- Enzensberger, Hans Magnus (1972). El corto verano de la anarquía. Vida y muerte de Durruti (in Spanish).

- Gallego, Ferran (2008). La crisis del antifascismo: Barcelona, mayo de 1937 (in Spanish). Barcelona: DeBolsillo. ISBN 978-84-8346-598-1. OCLC 433855847.

- González Martínez, Carmen (1999). Guerra civil en Murcia. Un análisis sobre el poder y los comportamientos colectivos (in Spanish). Murcia: Universidad de Murcia. ISBN 84-8371-096-X.

- Leval, Gastón (1975). Collectives in the Spanish Revolution. London: Freedom Press. ISBN 978-1-62963-447-0.

- Mintz, Frank (2013). Anarchism and Workers' Self-Management in Revolutionary Spain. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 9781849350785.

- Orwell, George (1938). Homage to Catalonia. London: Secker and Warburg. ISBN 0141183055. OCLC 1154105803.

- Payne, Stanley G. (1970). The Spanish Revolution. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297001248. OCLC 132223.

- Peirats, José (2011). The CNT in the Spanish revolution. Oakland: PM Press. ISBN 9781604862072.

- Pérez Baró, Albert (1974). Treinta meses de colectivismo en Cataluña (in Spanish). Barcelona: Ariel. ISBN 84-344-24-76-2.CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

- Quilis Tauriz, Fernando (1992). Revolución y guerra civil. Las colectividades obreras en la provincia de Alicante 1936-1939 (in Spanish). Alicante: Instituto de Cultura «Juan Gil-Albert». ISBN 84-7784-994-7.CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

- Sewell, Amber J. (2007). "Las colectividades del Cinca Medio durante la guerra civil (1936-1938)". In Sanz Ledesma (ed.). Comarca del Cinca Medio (PDF). Tarragona. ISBN 978-84-8380-060-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 21, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- Thomas, Hugh (1961). The Spanish Civil War. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 0060142782.

- Tiana Ferrer, Alejandro (1987). Educación libertaria y revolución social. (España, 1936-1939) (in Spanish). Madrid: U.N.E.D. ISBN 84-362-2151-6.

Additional sources

- Aisa, Ferran (2000). Una historia de Barcelona (in Spanish). Barcelona: Virus.

- Alba, Víctor (1978). La Revolución española en la práctica, documentos del POUM (in Spanish).

- Amorós, Miquel (2009). José Pellicer, el anarquista íntegro. Vida y obra del fundador de la heroica Columna de Hierro (in Spanish). Barcelona: Virus. ISBN 978-84-92559-02-2.

- Amorós, Miquel (2003). La revolución traicionada. La verdadera historia de Balius y Los Amigos de Durruti (in Spanish). Barcelona: Virus. ISBN 84-96044-15-7.

- Amorós, Miquel (2006). Durruti en el Laberinto (in Spanish). Bilbao: Muturreko Burutazioak. ISBN 84-96044-73-4.

- Amorós, Miquel (2004). "Los historiadores contra la Historia", en Las armas de la crítica (in Spanish). Bilbao: Muturreko Burutazioak. ISBN 84-96044-45-9.

- Amorós, Miquel (2011). Maroto, el héroe, una biografía del anarquismo andaluz. Virus. ISBN 978-84-92559312.

- Beevor, Antony (2006). Battle for Spain the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-303765-X.

- Berthuin, Jérémie. La CGT-SR et la révolution espagnole - De l'espoir à la désillusion (Juillet 1936-décembre 1937) (in French). CNT-RP.

- Bolloten, Burnett (1991). The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. ISBN 0-8078-1906-9.

- Bookchin, Murray (1976). The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years, 1868–1936. Free Life Press. ISBN 187317604X.

- Borkenau, Franz (1937). The Spanish Cockpit: an Eye-Witness Account of the Political and Social Conflicts of the Spanish Civil War. London: Faber and Faber. OCLC 3191955.

- Bosch, Aurora (1983). Ugetistas y libertarios. Guerra civil y Revolución en el País Valenciano, 1936–1939 (in Spanish). Valencia: Institución Alfonso el Magnánimo.

- Brenan, Gerald (1962). El Laberinto español. París: Ruedo Ibérico.

- Fraser, Ronald (1979). Blood of Spain: An Oral History of the Spanish Civil War. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-48982-9.

- Dolgoff, Sam (1974). The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939. Black Rose Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-919618-20-6.

- García Oliver, Juan (2008). El eco de los pasos (in Spanish). Barcelona: Planeta. ISBN 978-84-08-08253-8.