Housing in New Zealand

Housing in New Zealand was traditionally based on the quarter-acre block, detached suburban home, but many historical exceptions and alternative modern trends exist. New Zealand has largely followed international designs. From the time of organised European colonization in the mid-19th century there has been a general chronological development in the types of homes built in New Zealand, and examples of each generation are still commonly occupied.[1][2]

Types of places where people live

Traditionally, residential sections were quarter acre[3] (roughly 1000 sq m), but typical section sizes have been getting much smaller since the middle of the 1900s.[4] After a series of controversies over slum-like housing for the urban poor, from 1936 the then Labour government created State housing - suburban housing built by the government an rented to poorer families. This housing stock was generally very well built and remains a feature in most cities, although now often privately owned.[5] New Zealand cities are becoming more dense.[6] Many old office blocks and church buildings have been converted to apartments in New Zealand's major centres.[7][8]

Holiday and mobile homes

A small, often very modest holiday home or beach house, called a bach (pronounced "batch") in most of the country, but a "crib" in the lower South Island.[9] are used on a temporary basis as holiday accommodation. These are typically purpose built houses or huts next to a coast or a lake, but can also be used as a base for hunting or fishing in local rivers.[10] They are well known for a rustic, minimalist and mismatched internal design and furniture. However, large expensive holiday homes are also less commonly called baches.

Tents, camper-vans and caravans are also common, however New Zealand lacks the large trailer parks of some similar countries.

A new movement to build tiny homes [11]

There also a large range of wilderness huts in New Zealand, but staying in them for more than three days at a time is discouraged.[12]

Homelessness

Many New Zealanders live permanently in structures which were not designed to be homes and are counted as homeless by the government. Homelessness is a difficult statistic to measure and in New Zealand is not typically recorded with same accuracy as other statistics. In 2013 it was estimated by the census that 1% of people in New Zealand live in "severe housing deprivation". This number has increased from previous years.[13]

In May 2018 the government allocated $100 million to address homelessness over the next four years.[14]

House design

In 1990 the average new homes was 125 square metres, by 2017 this had grown to 195 square metres.[15] In 1966 the New Zealand Encyclopedia recognized seven basic designs of New Zealand houses.[16]

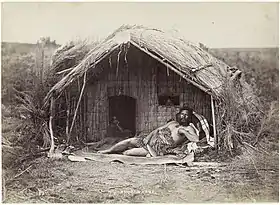

13th to early-19th century: Adapting a tropical culture to a temperate climate

At first Māori used the building methods that had been developed in tropical Polynesia, altered to fit the more nomadic lifestyle. By the 15th century Classic Māori communities slept in rectangular sleeping houses (wharepuni). The wharepuni were made of timber, rushes, tree ferns and bark, they had a thatched roof and earth floors.[17] These building also had a front porch which was an adaptation to New Zealand's climate and is not found in tropical Polynesia. The effect of European housing methods led to a mix of designs with Maori adopting windows and high roofs.

19th century: Building a better Britain

.jpg.webp)

Houses from this period are divided into cottages and villas. The first houses built in New Zealand were cottages.[18] Villas were the larger and more expensively built equivalent. The typical villa has the kitchen to the rear of the house and separate from the dining room, as food preparation was meant to occur out of sight.[19]

Early-20th century: American influences and responses

.jpg.webp)

The 20th century started with big Edwardian houses and neo-Georgian architecture[20] From the late 1910s the Californian bungalow became more popular. the design has a lower pitched roof and ceiling height than the typical New Zealand villa and was therefore easier to heat.[18] This coincided with the popularity of the Hollywood film industry, which incorporated American clothes, furniture, cars and houses.

As a response to American influence and nostalgia for Britain a style of houses were built which conspicuously emulated older English styles. Spanish mission style from the late 1920s with grand triple arches and twisted Baroque columns.[21] Modernism (Art deco) of the 1930 was designed to be functional with smooth surfaces and a flat roof.[22]

Late-20th century: Neo-colonial and Mediterranean styles

State housing had a big influence on the way homes were built in New Zealand from the 1940s to the late 1960s.[23]

21st century building habits

In the early 21st Century New Zealanders built in variety of styles that borrowed from a variety of previous influences.[18]

Integration with the environment

In some conspicuous locations in area of natural beauty it is required by local councils to blend the house design with the surrounding environment.[24]

Passive climate control

Houses can be built to maximize the heat gained during the day from the sun and retain it overnight.[25]

Utilities

Heating and insulation

Insulation in ceilings, walls and floor became mandatory for new builds and additions in 1978.[28][29] Glass fibre, polyester, polystyrene, wool and paper are all used for insulation in New Zealand.[30] Home insulation in New Zealand can be heavily subsidised by the government.[30]

According to the 2018 New Zealand census, heat pumps were the most common form of space heating, with 47.3% of households using them as their primary heating appliance. Other common forms of space heating were electric resistance heaters (44.1%) and wood burners (32.3%).[31]

Some local councils are restricting the kind of wood and coal burners that can be used in order to improve air quality.[32]

Water and sewerage

In 2017 about 80% of New Zealanders were on water purification distribution systems that supplied more than 100 people. Of these 96% met the bacteriological standards for water quality, while 81% met all the relevant standards.[33] The remaining 20% of New Zealanders typical live In rural areas where rain, streams and bores are commonly used as water sources.

Large properties can process or store their sewage on site.[34] Grey water can be reused for purposes other than drinking. This recycling is required by some New Zealand councils.[35]

Construction and regulations

The Building Act 1991 was replaced by the Building Act 2004,[36][37] this introduced a licensing for building designers, builders and related trades. Councils were required to be subject to regular quality control procedure checks, however, council building inspectors remained unlicensed.[38]

Alteration regulations

Most alterations to homes need to be certificated, there are also limits on houses of historical importance.

Illegal building practices

While all building practices that do not comply with the Building Act are illegal, some are also specifically banned.[39]

Foundations

Three broad categories are available for suburban house foundations concrete slab, a concrete block basement foundations and an elevated floor with a crawl space.[40] Footing depth varies with soil type and slope, with either a floating polystyrene slab or more rarely piling.

Earthquake risk and construction

Earthquakes can occur anywhere in New Zealand, but the risk to building structures is highly regional, with the eastern North Island and western South Island having the highest risk.[41] After the 2011 Christchurch earthquake a major review changed the boundaries and construction rules.[42][43]

Home ownership and economics

In 2017 63% of New Zealanders owned their own home this includes those who have an outstanding mortgage on their property and 33% live in rental properties.[44] This is the lowest rate of home ownership since 1951. This is partly due to the increase in New Zealand house prices which since 1990 have increased faster than any other OECD country.[15]

Government involvement

References

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "3. – Housing – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- "Early Housing in New Zealand — With particular reference to Nelson and Cook Strait Area | NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- See The Half-Gallon Quarter-Acre Pavlova Paradise

- Howie, Cherie (13 June 2019). "Our shrinking backyards: Death of the quarter-acre dream". NZ Herald. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Swings in National Housing Policy" (PDF). Auckland Regional Public Health Service. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- "'Unliveable': Five townhouses less than 1m away". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Robb, Robb (9 October 2015). "Departments to apartments". NBR. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Winter, Chloe (15 October 2015). "Former Wellington offices being converted to apartments". Stuff. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "Is it a crib or a bach?". Otago Daily Times Online News. 2012-12-28. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "5. – Beach culture – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- "Tiny houses". New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- "Huts". www.doc.govt.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- derek.cheng@nzherald.co.nz, Derek Cheng (2018-02-11). "Homeless crisis: 80 per cent to 90 per cent of homeless people turned away from emergency housing". NZ Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- "Government announces $100m plan to fight homelessness". Stuff. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- Andrew Coleman (2017-05-15). "Why does New Zealand keep building such massive houses?". The Spinoff. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- McLintock, Alexander Hare; James Garrett, A. N. Z. I. A.; Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Characteristic House Types – Seven Basic Styles". An encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, 1966. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Māori housing – te noho whare – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "3. – Housing – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- "Design: Styles of the city". NZ Herald. 2000-06-30. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "2. – Domestic architecture – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- McLintock, Alexander Hare; James Garrett, A. N. Z. I. A.; Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Characteristic House Types – Seven Basic Styles". An encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, 1966. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- Ltd, BRANZ (2010-08-07). "History | BRANZ Renovate". History. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- Ltd, BRANZ (2010-07-16). "1940-60s | BRANZ Renovate". 1940-60s. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- "Waitakere Ranges heritage area bush design guide" (PDF). www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz. 2017.

- Ltd, BRANZ (2018-12-12). "Key features of designing a home with passive design". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Natural Building Techniques". Earth Building Association of New Zealand. 2015-08-02. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- "Earth Building Association of New Zealand". Earth Building Association of New Zealand. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- "Shivers: Minimum insulation standards a must (+competition)". NZ Herald. 2012-08-04. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- "Thermal insulation required in NZ homes | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- "Paying for home insulation". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- "2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights (updated) | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- "Timaru resident's firewood spend doubles with new burner". Radio New Zealand. 2018-06-11. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- "Annual Report on Drinking-water Quality 2016-2017". Ministry of Health NZ. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Employment, Ministry of Business, Innovation and (2016-12-14). "Onsite sewage systems - Smarter Homes Practical advice on smarter home essentials". Smarter Homes. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Employment, Ministry of Business, Innovation and (2016-12-14). "Reusing greywater - Smarter Homes Practical advice on smarter home essentials". Smarter Homes. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- Employment, Ministry of Business, Innovation and. "Building Act 2004". Building Performance. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Employment, Ministry of Business, Innovation and. "Building Code compliance". Building Performance. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- "Failings of the Building Act 1991 – Were these a cause of the leaky building crisis? Breaking down the Building Act 2004: What does it really mean? « Legal Vision – Leaky Building Lawyers". Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Employment, Ministry of Business, Innovation and. "Warnings and bans on building products". Building Performance. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- "House Foundations - The Pros & Cons of 3 Different Types". Home Ownership Tips, Guides, Tricks and Tradespeople. 2015-03-04. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- "Earthquake risk zones » Seismic Resilience". www.seismicresilience.org.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- "Major changes to earthquake strengthening rules". Stuff. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- Bull, William B. (1996). "Prehistorical earthquakes on the Alpine fault, New Zealand". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 101 (B3): 6037–6050. Bibcode:1996JGR...101.6037B. doi:10.1029/95JB03062. ISSN 2156-2202.

- corazon.miller@nzherald.co.nz @c0ra_z0n, Corazon Miller Reporter, NZ Herald (2017-01-09). "Home ownership rates lowest in 66 years according to Statistics NZ". NZ Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2018-12-09.