New Zealand property bubble

The property bubble in New Zealand is a major national economic and social issue. Since the early 1990s, house prices in New Zealand have risen considerably faster than incomes,[1] putting increasing pressure on public housing providers as fewer households have access to housing on the private market. The property bubble has produced significant impacts on inequality in New Zealand, which now has the highest homelessness rate in the OECD[2] and a record-high waiting list for public housing.[3] Government policies have attempted to address the crisis since 2013, but have produced limited impacts to reduce prices or increase the supply of affordable housing.

Background

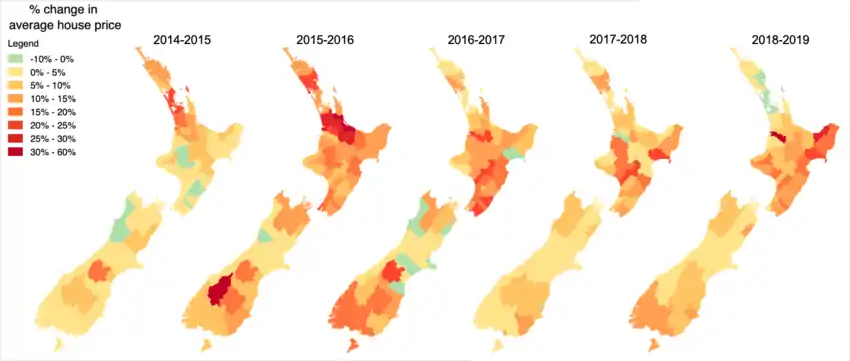

A house price bubble is defined as a period of speculative purchases, where investors demonstrate willingness to pay a high price today because they believe that it will be as high (or higher) tomorrow.[4] A 2016 study found evidence of a bubble in the New Zealand housing market from 2003, which stalled in 2007/8 with the impacts of the global financial crisis. A second bubble appeared in 2013, and until 2015 there were no notable spillover effects to other regions.[5] However, from 2015 onwards, rapid price growth is evident across smaller centres.

Housing in New Zealand has been strongly shaped by colonisation, post-war state intervention and economic and financial reforms since the 1980s.

The fourth Labour Government (elected in 1984) rapidly introduced policies of economic deregulation,[6] as a result of the previous Prime Minister Robert Muldoon's Think Big policies that had left the country heavily in debt.[7] Investment in shares increased rapidly, often with little due diligence carried out.[8][9] The 1987 sharemarket crash hit New Zealand's economy especially hard,[10] with the NZSE dropping around 60% from its peak.[11][12] Many investors who lost heavily in the 1987 crash never returned to the sharemarket, instead opting for the safer option of property investment.[13][14][10][9]

In 1989 Parliament passed the Reserve Bank Act, which emphasised keeping a lid on inflation and on interest rates, which in turn reduced the costs of borrowing for fixed assets such as houses. In the same year, tax exemptions for pension, insurance and other similar investments were abolished, but not for real estate. Two years later, the Resource Management Act (RMA) replaced a raft of regional-planning laws. Some regard the RMA as an obstacle to building affordable housing.[15]

Alongside institutional reforms in the housing sector, problems with poor-quality construction, historic injustices and under-provision for the needs of indigenous Māori,[16] and persistent income inequality,[17] the lack of affordable housing is a critical issue. Since the Global Financial Crisis, the rapid growth of prices has created an affordable housing crisis and housing has been a prominent issue on political agendas since 2013. Despite a number of policy interventions to address the crisis, prices have continued to grow across the country. As shown below, real house prices increased almost three-fold between 2000 and 2018.[18]

Affordability crisis

While house prices increased almost-continuously from the early 1990s, it was not until the 2007 that the media started reporting an affordability crisis.[19] Nationwide, property prices increased 80% in real terms between 2002 and 2008.[20] The Global Financial Crisis caused a 10% drop in nominal prices in 2008, however price growth picked up again significantly following the crisis and by 2014, nominal prices in Auckland were 34% higher than the pre-crisis peak.[21]

As of 2019, the average house price in New Zealand exceeded NZ$700,000, with average prices in the country's largest city, Auckland, exceeding $1,000,000 in numerous suburbs.[22] The ratio between median house price and median annual household income increased from just over 3.0 in January 2002 to 6.27 in March 2017, with Auckland's figures 4.0 to 9.81 respectively.[23][24]

In 2017, the Demographia think-tank ranked Auckland's housing market the fourth-most unaffordable in the world—behind Hong Kong, Sydney and Vancouver—with median house prices rising from 6.4 times the median income in 2008 to 10 times in 2017.[25] Another study carried out in 2016 reported that average house prices in Auckland surpassed those of Sydney.[26] That same year, the International Monetary Fund ranked New Zealand at the top for housing unaffordability in the OECD,[27] and has called for taxation of property speculation.[28]

Multiple property owners in New Zealand are not subject to capital gains taxes and can use negative gearing on their properties, making it an attractive investment option.[29][30] Prospective house-buyers, however, accuse property investors of crowding them out.[31] When the Tax Working Group reported its findings to Parliament in 2019, a capital gains tax was among its recommendations, only to be shelved after failing to secure enough Parliamentary backing.[32]

According to NZ's 2017 register of pecuniary interests,[33] New Zealand's 120 members of parliament own more than 300 properties between them,[34][35][36] prompting accusations of conflict of interest.[37]

NIMBY sentiment among established home-owners—particularly towards attempts to relax building density rules in Auckland such as the Unitary Plan[38]—has also been pointed to as a major factor in the housing bubble.[39][40][41][42][43]

Regional dynamics

The house price bubble first emerged in Auckland, and subsequently spread to other areas of the country. The figure below shows the regional changes in average house price, between 2014 and 2019.[44]

Social impacts of the affordability crisis

Unaffordable housing has produced profound impacts on New Zealand society. Between 1986 and 2013, home ownership dropped from 74% to 65%.[45]

The most recent statistics on homelessness, from the 2013 Census, showed that 1% of the population were living in severe housing deprivation. Of this population 71% are temporarily resident in severely crowded private dwellings, 19% live in commercial dwellings or marae, and 10% live on the street or in a car.[46] Between 2017 and 2019, the waiting list for public housing doubled, reaching a record 12,500 in August 2019.[47] In 2018, a report found that emergency housing providers were turning away 80-90% of those seeking assistance.[48]

| Year | Eligible families and individuals waiting for public housing |

|---|---|

| Sep-14 | 4,189 |

| Sep-15 | 3,399 |

| Sep-16 | 4,602 |

| Sep-17 | 5,844 |

| Sep-18 | 9,546 |

| Sep-19 | 13,966 |

The substantial growth of property prices over recent decades has significantly influenced the distribution of wealth in New Zealand. The 2019 Rich List showed that eight of the top 25 wealthiest people made their money from property, and 16 of the 20 new additions to the list also became wealthy through property investment. Rising prices have been attributed to various factors including deregulation, immigration and politics, with considerable debate over how to address the issue due to its large size relative to the economy.

Policy responses

Policies to address the housing affordability crisis cover land use and planning regulation, state housing provision, rules on ownership and investment, and financial regulation.

Special Housing Areas

In 2013, the government passed the Housing Accord and Special Housing Areas Act 2013, introducing Special Housing Areas (SHAs) to increase land supply in urban areas. Within designated SHAs, developments larger than 14 dwellings were required to allocate 10% of housing at 'affordable' prices. Affordability was defined as 75% of the region's median house price, or a price at which households earning up to 120% of median household income would spend no more than 30% of gross income on rent or mortgage repayments. Research showed that little evidence for the effectiveness of this policy to improve affordability.[49] The act was not extended beyond 2019, after generating disappointing results.[50]

From 2016, the housing development planned by Fletcher Building on a designated Special Housing Area at Ihumātao was opposed by protesters, who set up a camp at the site. Opponents contended that the land was confiscated during the Waikato War in 1863, in breach of the Treaty of Waitangi. In 2017 the United Nations recommended that the New Zealand Government review the designation of Ihumātao as a Special Housing Area, drawing attention to potential breaches of human rights.[51] In 2019, after protestors were served an eviction notice and police presence escalated, the prime minister announced that no development would take place at Ihumātao while the government attempted to broker a solution.[52]

Bright-line test

In October 2015 the government introduced a bright-line test to reduce speculative investment. This test applies to all property acquired after the law was introduced, and taxes capital gains at the same level as the seller's income tax rate.[53]

Loan-to-value restrictions

The loan-to-value ratio measures how much a bank lends for a property, compared to the property's total value. Loan-to-value (LVR) restrictions were first introduced in 2013 by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. The restrictions comprised a 'speed limit' on the proportion of high-LVR loans that banks can issue, and a threshold defining high-LVR loans.[54]

Initial LVR restrictions in October 2013 restricted banks to no more than 10% of loans beyond 80% LVR. In 2015, the restrictions were revised to target price inflation in Auckland, easing the restrictions to 15% over 80% LVR for non-Auckland loans, and increasing to 5% over 70% LVR for investor purchases in Auckland. In 2016 the restrictions tightened further on Auckland investors, to 5% over 60% LVR.

Since 2018, LVR restrictions gradually reduced to 20% over 80% for owner-occupiers, and 5% over 70% for investors. In April 2020 the Reserve Bank lifted restrictions on mortgage borrowing in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, to ensure that the LVR rules did not unduly affect lenders or borrowers as part of the mortgage deferral scheme introduced in response to the pandemic.[55]

The Reserve Bank has suggested that the targeted restriction for Auckland properties in 2015 may have contributed to price inflation in other regions.[56]

National Policy Statement on Urban Development capacity (NPS-UDC)

The NPS-UDC is planned to be replaced by the National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD), which the government consulted on in 2019.

The purpose of the NPS-UDC, introduced in 2016, was to ensure that sufficient development capacity was provided by local authorities, to meet demand for land for housing and commercial use. The NPS-UDC provided targeted measures for high-growth areas.

Foreign ownership ban

In August 2018, a law was passed a ban non-resident foreigners from buying existing homes,[57] delivering on the New Zealand First Party's election promise. The law allows non-residents to own up to 60% of units in new-build apartment blocks, however, they are not permitted to buy existing homes. Immigration remains a topic of controversy in regards to housing affordability, and has been cited by the Reserve Bank and others as a factor in rising house prices. Annual net migration as of 2017 was approximately 70,000, compared with an average of 15,000 in the previous 25 years.[58][59] However the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment has refuted this, saying that New Zealanders returning from overseas make up much of the inflows, and that there was a need to allow in "skilled migrants required to ramp up housing supply".[60] In 2015 it was reported that Auckland had over 33,000 "ghost" properties that were registered as unoccupied, many of them believed to be owned by absentee foreigners.[61]

Extension of bright-line test

The bright-line test introduced under the previous administration was extended to five years, to reduce incentives for speculative investment. The five-year rule applies to properties purchased after March 2018, and the main family home is exempt.[62] Changes in legal ownership for a property can count as a disposal, and 'reset the clock' on the five-year limit, even if the property is substantively owned and controlled by the same person.[63]

State housing construction

In December 2017, the Sixth Labour Government stopped the sale of Housing New Zealand properties,[64] and committed to expanding the supply of public housing.

KiwiBuild

KiwiBuild was the flagship housing policy of the Sixth Labour Government of New Zealand, proposing to deliver 100,000 houses in ten years to address the affordability crisis. The scheme planned to boost housing supply by giving property developers more incentives to deliver affordable homes rapidly. This included the Land for Housing programme, which acquired vacant land, on-selling to developers, with conditions of making 20% of dwellings available for public housing and delivering 40% 'affordable' housing according to KiwiBuild criteria. The scheme also purchased properties off-the-plans from developers, to sell to eligible buyers.[65] Construction sector capacity to deliver KiwiBuild's targets was identified as a challenge, and the government introduced a KiwiBuild Shortage List, allowing accredited construction employers to accelerate the immigration process for construction workers.[66]

Criticism of the policy highlighted that the prices of KiwiBuild homes remained out of reach for many, with 'affordable' properties costing upward of NZD$500,000 in Auckland, and NZD$300,000-500,000 across the rest of the country.[67] By September 2019, only 258 houses had been delivered by the scheme, well below the targets.[68] The uptake also showed that the Kiwibuild homes did not attract buyers, with unsold homes released onto the private market in some regions.[68]

KiwiBuild reset

A 'reset' of KiwiBuild was released in 2019, following the reshuffle of ministerial responsibilities for housing and appointment of Dr. Megan Woods as Minister for Housing.[69] The revised policy dropped the target to build 100,000 houses in ten years and introduced rent-to-buy and shared equity options to improve affordability. The requirement for first-home buyers to hold their Kiwibuild homes for at least three years was reduced to one year.

National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD)

The NPS-UD was consulted on in October 2019, to replace and expand on the 2016 NPS-UDC. The NPS-UD has a similar purpose to its predecessor, to enable growth in new areas by removing unnecessary restrictions, targeted to high-growth areas.

The discussion document included a range of requirements for councils, including:

- New objectives for Future Development Strategies, to ensure that growth is coordinated and responsive to demand

- Allow growth through intensification and greenfield development, in a way that contributes to a quality urban environment

- Develop and maintain evidence base on demand and prices for housing and land

- Ensure planning is co-ordinated across urban areas, taking into account issues of concern for iwi and hapū

The NPS-UD is planned for implementation by mid-2020.

Alternative solutions considered

Capital gains tax

There is currently no tax on capital gains from property investment in New Zealand. The bright-line test introduced in 2015 and extended in 2018 aims to tax capital gains on property, however the main family home, estates, or properties sold through relationship settlements are exempt.

In late 2017, the Labour Government established the Tax Working Group, an advisory group to examine improvements to the fairness and balance of the tax system. The group published its report in February 2019, recommending a tax on capital gains that applies to gains and most losses related to all types of land and improvements, except for the main family home.[70] This tax would apply to rental and second homes, business assets, land and shares. Following robust public and media debate, the government abandoned their plan to introduce the capital gains tax, citing a lack of consensus within government.[71]

Land value tax

Land value taxation has been suggested by a series of commentators, including Dr. Arthur Grimes and Dr. Andrew Coleman,[72] Dr. Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy,[73] economist Shamubeel Eaqub and Bernard Hickey.[74]

Land use reform

In September 2015, the New Zealand Productivity Commission released a comprehensive report on Using land for housing, commissioned by the government to review local council processes for providing land for housing, with a focus on fast-growing areas. According to the report, insufficient supply of developable brownfield and greenfield land was a major contributor to house price growth between 2000 and 2015. It proposed reform in a range of areas:

- Lifting restrictive planning controls in areas with spare capacity on existing infrastructure networks

- More effective cost-recovery of infrastructure costs

- Greater use of cost-benefit analysis for land use rules

- Granting local urban development authorities (UDAs) more power to develop housing

- Powers for central government to intervene to ensure sufficient development capacity is released, if councils are unable to release land (this was implemented through the 2016 National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity).

Debt-to-income limits

In 2017 the Reserve Bank of New Zealand published a consultation paper on debt-to-income limits, as a tool to restrict credit growth and mitigate the risk of mortgage defaults during an economic downturn. High levels of private debt present a significant macro-economic risk. It reduces household consumption by diverting a large proportion of income to servicing debts and also makes households vulnerable to economic shocks.[75]

Potential effects of bubble burst

According to investment manager Brian Gaynor in 2012, a 10% drop in house prices would wipe out $60 billion of New Zealanders' personal wealth, which would exceed the losses from the 1987 sharemarket crash.[8] Steve Keen, one of the few economists to forecast the Great Recession, warned in mid-2017 that New Zealand would be one of many nations to experience a private debt meltdown involving housing, and that "the bubble will burst in the next one to two years".[76] A report published by Goldman Sachs predicted that New Zealand had a 40% chance of a "housing bust" over the same period.[77] Financial commentator Bernard Hickey has described New Zealand's property market as "too big to fail", and supports a deposit insurance scheme in the event of a banking collapse caused by a property crash.[78]

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has estimated that the total value of housing loans has increased from just under $60 billion in 1999 to over $220 billion in 2016.[79]

See also

- Housing in New Zealand

- KiwiBuild

- Real estate bubble

- Taxation in New Zealand

- New Zealand dream – aspirations of owning a property

References

- Bernard Hickey (2009-08-17). "Opinion: Why the golden oldies are wrong: housing is less affordable now than in 1987 and 1975 (Corrected)". interest.co.nz.

- Barrett, Jonathan (May 20, 2018). "Left behind: why boomtown New Zealand has a homelessness crisis". Reuters.

- Cooke, Henry (August 20, 2019). "Public housing waitlist at new high with 12,644 households waiting months for housing". Stuff.

- Stiglitz, J.E. (1990). “Symposium on bubbles”. In: Journal of Economic Perspectives Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 13-18

- Greenaway-McGrevy, R. (2015). "Hot property in New Zealand: Empirical evidence of housing bubbles in the metropolitan centres". New Zealand Economic Papers. 50 (1): 88–113. doi:10.1080/00779954.2015.1065903. hdl:2292/25259.

- "Government and market liberalisation". Te Ara Encyclopedia of NZ.

- Owen Hembry (2011-01-30). "In the shadow of Think Big". New Zealand Herald.

- Gaynor, Brian (2012-10-20). "Property fallout would top '87 share crash". New Zealand Herald.

- Nadine Higgins (2017-09-07). "Eyewitness: Black Monday". Radio New Zealand.

- Liam Dann (2017-10-12). "The Crash". New Zealand Herald.

In October 1987 a stock market crash shook the world. Nowhere was hit harder than New Zealand.

- "Share Price Index, 1987–1998". Archived from the original on 2010-05-25.

- "Commercial Framework: Stock exchange, New Zealand Official Yearbook 2000". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Tony Field (2016-08-03). "Shares outperform property, but not popular investment choice". Newshub.

Mr Beale says Kiwis naturally don't like investing, and are very focussed on property, with memories of the 1987 crash still lingering.

'It seems New Zealand is still not investing in the share market because of what happened in the 1987 sharemarket crash.' - "The touch factor". New Zealand Herald. 2005-02-15.

The allure of property investment is quite multifaceted. To some it is the touchy, feely factor. They can buy a property, drive past it and touch it, which is something they can't do with shares and bonds.[...] Others have had bad experiences with shares (think the 1987 sharemarket crash, investors who got burnt haven't forgotten) and other savings schemes and are looking for alternative forms of investment.

-

Bernard Hickey (2017-04-19). "1989 was year zero for Generation Rent". Newsroom.co.nz.

As the Productivity Commission and the current government has pointed out repeatedly in recent years, the RMA ushered in an era where councils and residents were more reluctant to open up land for housing, partly because it was easier to object to new developments, and partly because the funding arrangements for councils made it more difficult.

The end result was New Zealand's house building rate dropped from around nine homes per 1,000 people per year during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s to around five homes per 1,000 people through the 1990s and 2000s. The potential for extra housing supply to both respond to higher house prices and then soften the growth was ripped out by the effects of the RMA and council funding mechanisms. - "Part 2: Māori housing needs and history, and current government programmes". Office of the Auditor-General New Zealand. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "The truth about inequality in New Zealand". Stuff. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- OECD Economic Surveys: New Zealand 2019

- "Your views: How to afford a house in New Zealand". New Zealand Herald. 22 January 2007.

- House Prices Unit (2008) Final Report of the House Prices Unit: House Price Increases and Housing In New Zealand. Wellington: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Murphy, L. (2015). "The politics of land supply and affordable housing: Auckland's Housing Accord and Special Housing Areas". Urban Studies. 53 (12): 2530–2547. doi:10.1177/0042098015594574.

- Fyers, Andy (2016-12-04). "Blowing Bubbles: Where the housing bubble has blown up the biggest". Stuff.co.nz/Business Day.

- David Chaston. "Median Multiples - House price-to-income multiple". interest.co.nz.

- "New Zealand average house price tops $700k for first time". RNZ. 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- Patrick O'Meara (2017-01-23). "Housing in many NZ cities 'severely unaffordable'". RNZ.

- Andrew Laxon (2016-09-25). "Home truths: City of expensive sales tops Sydney". New Zealand Herald.

- Dan Satherley (2016-09-01). "No fix for housing crisis until young and renters vote - economist". Newshub.

- Hamish Rutherford (2017-05-09). "IMF says housing bubble could unsettle strong New Zealand economy". Stuff.co.nz.

- Simmons, Geoff (2016-06-17). "Why a capital gains tax won't stop the housing bubble". National Business Review.

- Small, Vernon (2017-05-14). "Labour to shut down 'negative gearing' tax break in crackdown on property investors". Sunday Star Times.

- "Are investors crowding first-home buyers out of the market?". New Zealand Herald. 2016-04-26.

- "'No mandate' for capital gains tax - PM". Radio New Zealand. 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- Sir Maarten Wevers (2017-01-31). "Register of Pecuniary and Other Specified Interests of Members of Parliament: Summary of annual returns as at 31 January 2017" (PDF). New Zealand Parliament.

- Nicholas Jones and Isaac Davison (2017-05-09). "MPs' latest home ownership, interests revealed". New Zealand Herald.

- Stacey Kirk and Andy Fyers (2017-05-10). "The many houses of our MPs - which MPs have a stake in multiple properties?". Stuff.co.nz.

- "Government MPs' property ownership revealed". RNZ News. 2017-05-10.

- "MPs' housing investments 'no conflict'". RNZ News. 2015-05-11.

- "Auckland Unitary Plan". Auckland Council. 2016-11-15.

- "Group considers legal challenge to Unitary Plan". RNZ News. 2016-07-28.

- Maria Slade (2016-02-25). "Great dollops of nimbyism lock first home buyers out of Auckland upzoning debate". Auckland Now.

- Geoff Simmons (2016-07-29). "Unitary Plan: Inevitable NIMBY backlash begins". National Business Review.

- Rob Stock (2018-04-22). "Housing NZ complex shows Auckland's 'Nimby nightmare' unitary plan in action". Stuff.co.nz.

- Dileepa Fonseka and Joel Maxwell (2019-08-21). "Hopes anti-NIMBY announcement will help 'awful' process of building more houses in Wellington". Stuff.co.nz.

- "Residential House Values". www.qv.co.nz. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- Statistics New Zealand (2015). Dwelling and tenure type tables for Auckland from 2013 Census.

- Otago, University of. "3 June 2016, Homelessness accelerates between censuses". University of Otago. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Public housing waitlist at new high with 12,644 households waiting months for housing". Stuff. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- derek.cheng@nzme.co.nz, Derek Cheng Derek Cheng is a political reporter for the New Zealand Herald (2018-02-11). "Homeless crisis: 80 per cent to 90 per cent of homeless people turned away from emergency housing". ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- Fernandez, Mario A.; Sánchez, Gonzalo E.; Bucaram, Santiago (2019-03-16). "Price effects of the special housing areas in Auckland". New Zealand Economic Papers. 0: 1–14. doi:10.1080/00779954.2019.1588916. ISSN 0077-9954.

- "Government will not extend special housing areas law beyond September". Stuff. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Ihumātao: NZ breaching human rights obligations - The University of Auckland". www.auckland.ac.nz. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "PM blocks building at Ihumatao". Otago Daily Times Online News. 2019-07-26. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Govt to tighten tax on capital gains". RNZ. 2015-05-17. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Loan-to-value ratio restrictions FAQs - Reserve Bank of New Zealand". www.rbnz.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Reserve Bank removes LVR restrictions for 12 months - Reserve Bank of New Zealand". www.rbnz.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- "The Reserve Bank has undertaken a review of the loan to value ratio (LVR) restrictions and found they have been effective in improving financial stability but have 'an efficiency cost'". interest.co.nz. 2019-05-22. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "New Zealand passes ban on foreign homebuyers into law". Reuters. 2018-08-15. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- Mark Lister (2017-02-21). "Three things that could burst bubble". New Zealand Herald.

- Hamish Rutherford (2017-02-27). "Net migration hits 71,000 as Kiwis turn their back on living overseas". Stuff.co.nz/Business Day.

- Isaac Davidson (2016-08-10). "Migrants not to blame for Auckland's house prices, study finds". New Zealand Herald.

- Joanna Wane (2017-09-17). "Running on empty: The 'ghost homes' in Auckland's housing crisis". Metro Magazine.

- "Bright-line test period extended| NZ LAW". nzlaw.co.nz. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Tax matters : Beware the bright line property test". 2018-09-10. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Government announces end to state home selloff". Stuff. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- "Information for property developers | KiwiBuild". www.kiwibuild.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- admin (2018-06-28). "Kiwibuild visa replaced with new Kiwibuild skills shortage list". NZ Immigration Law. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Doubts over KiwiBuild's affordability". Newshub. 2018-02-25. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Labour's flagship policy: Where did KiwiBuild go wrong?". Newshub. 2019-04-09. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "PM takes housing off Phil Twyford in first major reshuffle". Stuff. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Future of Tax: Final Report". taxworkinggroup.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Capital gains tax abandoned by Government". Stuff. Retrieved 2019-11-01.

- "Fiscal, Distributional and Efficiency Impacts of Land and Property Taxes". Motu Economic & Public Policy Research. 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- "Auckland University's Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy extols the virtues of a land tax & how one would hit both landbankers and wealthy foreigners buying NZ land". interest.co.nz. 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- "Why a land tax is the best tax reform". Newsroom. 2018-03-22. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- OECD (2012). "Debt and Macroeconomic Stability" (PDF). OECD Economics Department Policy Note No 16. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Wallace Chapman (2017-05-28). "Steve Keen: The coming crash". RNZ.

- "NZ at 40% risk of housing bust - Goldman Sachs". RNZ News. 2017-05-16.

- Bernard Hickey (2014-04-28). "The problem of moral hazard in our 'Too Big To Fail' property market". Newsroom.co.nz.

- Andy Fyers (2016-12-07). "Blowing Bubbles: Who loses the most when a housing bubble bursts". Stuff.co.nz/Business Day.