Cinema of the United States

The cinema of the United States has had a large effect on the film industry in general since the early 20th century. The dominant style of American cinema is the classical Hollywood cinema, which developed from 1913 to 1969 and characterizes most films made there to this day. While Frenchmen Auguste and Louis Lumière are generally credited with the birth of modern cinema,[5] American cinema soon came to be a dominant force in the emerging industry. It produces the largest number of films of any single-language national cinema, with more than 700 English-language films released on average every year.[6] While the national cinemas of the United Kingdom (299), Canada (206), Australia, and New Zealand also produce films in the same language, they are not considered part of the Hollywood system. That said, Hollywood has also been considered a transnational cinema.[7] It produced multiple language versions of some titles, often in Spanish or French. Contemporary Hollywood often off-shores productions to Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

| Cinema of the United States (Hollywood) | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The Hollywood Sign in the Hollywood Hills, often regarded as a symbol of the American film industry | |

| No. of screens | 40,393 (2017)[1] |

| • Per capita | 14 per 100,000 (2017)[1] |

| Main distributors | |

| Produced feature films (2016)[2] | |

| Fictional | 646 (98.5%) |

| Animated | 10 (1.5%) |

| Number of admissions (2017)[3] | |

| Total | 1,239,742,550 |

| • Per capita | 3.9 (2010)[4] |

| Gross box office (2017)[3] | |

| Total | $11.1 billion |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United States of America |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

United States portal |

Hollywood is considered the oldest film industry where earliest film studios and production companies emerged, and is also the birthplace of various genres of cinema—among them comedy, drama, action, the musical, romance, horror, science fiction, and the war epic—having set an example for other national film industries.

In 1878, Eadweard Muybridge demonstrated the power of photography to capture motion. In 1894, the world's first commercial motion-picture exhibition was given in New York City, using Thomas Edison's kinetoscope. In the following decades, production of silent film greatly expanded, studios formed and migrated to California, and films and the stories they told became much longer. The United States produced the world's first sync-sound musical film, The Jazz Singer, in 1927,[8] and was at the forefront of sound-film development in the following decades. Since the early 20th century, the US film industry has largely been based in and around the 30 Mile Zone in Hollywood, Los Angeles, California. Director D.W. Griffith was central to the development of a film grammar. Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941) is frequently cited in critics' polls as the greatest film of all time.[9]

The major film studios of Hollywood are the primary source of the most commercially successful and most ticket selling movies in the world.[10] Moreover, many of Hollywood's highest-grossing movies have generated more box-office revenue and ticket sales outside the United States than films made elsewhere.

Today, American film studios collectively generate several hundred movies every year, making the United States one of the most prolific producers of films in the world and a leading pioneer in motion picture engineering and technology.

History

Origins and Fort Lee

The first recorded instance of photographs capturing and reproducing motion was a series of photographs of a running horse by Eadweard Muybridge, which he took in Palo Alto, California using a set of still cameras placed in a row. Muybridge's accomplishment led inventors everywhere to attempt to make similar devices. In the United States, Thomas Edison was among the first to produce such a device, the kinetoscope.

The history of cinema in the United States can trace its roots to the East Coast where, at one time, Fort Lee, New Jersey was the motion-picture capital of America. The industry got its start at the end of the 19th century with the construction of Thomas Edison's "Black Maria", the first motion-picture studio in West Orange, New Jersey. The cities and towns on the Hudson River and Hudson Palisades offered land at costs considerably less than New York City across the river and benefited greatly as a result of the phenomenal growth of the film industry at the turn of the 20th century.[11][12][13]

The industry began attracting both capital and an innovative workforce. In 1907, when the Kalem Company began using Fort Lee as a location for filming in the area, other filmmakers quickly followed. In 1909, a forerunner of Universal Studios, the Champion Film Company, built the first studio.[14] Others quickly followed and either built new studios or leased facilities in Fort Lee. In the 1910s and 1920s, film companies such as the Independent Moving Pictures Company, Peerless Studios, The Solax Company, Éclair Studios, Goldwyn Picture Corporation, American Méliès (Star Films), World Film Company, Biograph Studios, Fox Film Corporation, Pathé Frères, Metro Pictures Corporation, Victor Film Company, and Selznick Pictures Corporation were all making pictures in Fort Lee. Such notables as Mary Pickford got their start at Biograph Studios.[15][16][17]

In New York, the Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens, was built during the silent film era, was used by the Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields. The Edison Studios were located in the Bronx. Chelsea, Manhattan was also frequently used. Picture City, Florida was also a planned site for a movie picture production center in the 1920s, but due to the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane, the idea collapsed and Picture City returned to its original name of Hobe Sound. Other major centers of film production also included Chicago, Texas, California, and Cuba.

The film patents wars of the early 20th century led to the spread of film companies across the US. Many worked with equipment for which they did not own the rights to use and so filming in New York could be dangerous; as it was close to Edison's company headquarters, and close to agents the company set out to seize cameras. By 1912, most major film companies had set up production facilities in Southern California near or in Los Angeles because of the region's favorable year-round weather.[18]

Rise of Hollywood

In early 1910, director D. W. Griffith was sent by the Biograph Company to the west coast with his acting troupe, consisting of actors Blanche Sweet, Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford, Lionel Barrymore and others. They started filming on a vacant lot near Georgia Street in downtown Los Angeles. While there, the company decided to explore new territories, traveling several miles north to Hollywood, a little village that was friendly and enjoyed the movie company filming there. Griffith then filmed the first movie ever shot in Hollywood, In Old California, a Biograph melodrama about California in the 19th century, when it belonged to Mexico. Griffith stayed there for months and made several films before returning to New York. After hearing about Griffith's success in Hollywood, in 1913, many movie-makers headed west to avoid the fees imposed by Thomas Edison, who owned patents on the movie-making process.[19] Nestor Studios of Bayonne, New Jersey, built the first studio in Hollywood in 1911.[20] Nestor Studios, owned by David and William Horsley, later merged with Universal Studios; and William Horsley's other company, Hollywood Film Laboratory, is now the oldest existing company in Hollywood, now called the Hollywood Digital Laboratory. California's more hospitable and cost-effective climate led to the eventual shift of virtually all filmmaking to the West Coast by the 1930s. At the time, Thomas Edison owned almost all the patents relevant to motion picture production and movie producers on the East Coast acting independently of Edison's Motion Picture Patents Company were often sued or enjoined by Edison and his agents while movie makers working on the West Coast could work independently of Edison's control.[21]

In Los Angeles, the studios and Hollywood grew. Before World War I, films were made in several American cities, but filmmakers tended to gravitate towards southern California as the industry developed. They were attracted by the warm climate and reliable sunlight, which made it possible to film their films outdoors year-round and by the varied scenery that was available. War damage contributed to the decline of the then-dominant European film industry, in favor of the United States, where infrastructure was still intact.[22] The stronger early public health response to the 1918 flu epidemic by Los Angeles[23] compared to other American cities reduced the number of cases there and resulted in a faster recovery, contributing to the increasing dominance of Hollywood over New York City.[22] During the pandemic, public health officials temporarily closed movie theaters in some jurisdictions, large studios suspended production for weeks at a time, and some actors came down with the flu. This caused major financial losses and severe difficulties for small studios, but the industry as a whole more than recovered during the Roaring Twenties.[24]

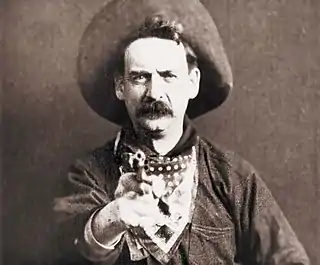

There are several starting points for cinema (particularly American cinema), but it was Griffith's controversial 1915 epic Birth of a Nation that pioneered the worldwide filming vocabulary that still dominates celluloid to this day.

In the early 20th century, when the medium was new, many Jewish immigrants found employment in the US film industry. They were able to make their mark in a brand-new business: the exhibition of short films in storefront theaters called nickelodeons, after their admission price of a nickel (five cents). Within a few years, ambitious men like Samuel Goldwyn, William Fox, Carl Laemmle, Adolph Zukor, Louis B. Mayer, and the Warner Brothers (Harry, Albert, Samuel, and Jack) had switched to the production side of the business. Soon they were the heads of a new kind of enterprise: the movie studio. (The US had at least two female directors, producers and studio heads in these early years: Lois Weber and French-born Alice Guy-Blaché.) They also set the stage for the industry's internationalism; the industry is often accused of Amero-centric provincialism.

Other moviemakers arrived from Europe after World War I: directors like Ernst Lubitsch, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang and Jean Renoir; and actors like Rudolph Valentino, Marlene Dietrich, Ronald Colman, and Charles Boyer. They joined a homegrown supply of actors — lured west from the New York City stage after the introduction of sound films — to form one of the 20th century's most remarkable growth industries. At motion pictures' height of popularity in the mid-1940s, the studios were cranking out a total of about 400 movies a year, seen by an audience of 90 million Americans per week.[25]

.jpg.webp)

Sound also became widely used in Hollywood in the late 1920s.[26] After The Jazz Singer, the first film with synchronized voices was successfully released as a Vitaphone talkie in 1927, Hollywood film companies would respond to Warner Bros. and begin to use Vitaphone sound — which Warner Bros. owned until 1928 – in future films. By May 1928, Electrical Research Product Incorporated (ERPI), a subsidiary of the Western Electric company, gained a monopoly over film sound distribution.[25]

A side effect of the "talkies" was that many actors who had made their careers in silent films suddenly found themselves out of work, as they often had bad voices or could not remember their lines. Meanwhile, in 1922, US politician Will H. Hays left politics and formed the movie studio boss organization known as the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA).[27] The organization became the Motion Picture Association of America after Hays retired in 1945.

In the early times of talkies, American studios found that their sound productions were rejected in foreign-language markets and even among speakers of other dialects of English. The synchronization technology was still too primitive for dubbing. One of the solutions was creating parallel foreign-language versions of Hollywood films. Around 1930, the American companies opened a studio in Joinville-le-Pont, France, where the same sets and wardrobe and even mass scenes were used for different time-sharing crews.

Also, foreign unemployed actors, playwrights, and winners of photogenia contests were chosen and brought to Hollywood, where they shot parallel versions of the English-language films. These parallel versions had a lower budget, were shot at night and were directed by second-line American directors who did not speak the foreign language. The Spanish-language crews included people like Luis Buñuel, Enrique Jardiel Poncela, Xavier Cugat, and Edgar Neville. The productions were not very successful in their intended markets, due to the following reasons:

- The lower budgets were apparent.

- Many theater actors had no previous experience in cinema.

- The original movies were often second-rate themselves since studios expected that the top productions would sell by themselves.

- The mix of foreign accents (Castilian, Mexican, and Chilean for example in the Spanish case) was odd for the audiences.

- Some markets lacked sound-equipped theaters.

In spite of this, some productions like the Spanish version of Dracula compare favorably with the original. By the mid-1930s, synchronization had advanced enough for dubbing to become usual.

Classical Hollywood cinema and the Golden Age of Hollywood (1913–1969)

Classical Hollywood cinema, or the Golden Age of Hollywood, is defined as a technical and narrative style characteristic of American cinema from 1913 to 1969, during which thousands of movies were issued from the Hollywood studios. The Classical style began to emerge in 1913, was accelerated in 1917 after the U.S. entered World War I, and finally solidified when the film The Jazz Singer was released in 1927, ending the Silent Film era and increasing box-office profits for film industry by introducing sound to feature films.

Most Hollywood pictures adhered closely to a formula – Western, Slapstick Comedy, Musical, Animated Cartoon, Biographical Film (biographical picture) – and the same creative teams often worked on films made by the same studio. For example, Cedric Gibbons and Herbert Stothart always worked on MGM films, Alfred Newman worked at 20th Century Fox for twenty years, Cecil B. De Mille's films were almost all made at Paramount, and director Henry King's films were mostly made for 20th Century Fox.

At the same time, one could usually guess which studio made which film, largely because of the actors who appeared in it; MGM, for example, claimed it had contracted "more stars than there are in heaven." Each studio had its own style and characteristic touches which made it possible to know this – a trait that rarely exist today.

For example, To Have and Have Not (1944) is famous not only for the first pairing of actors Humphrey Bogart (1899–1957) and Lauren Bacall (1924–2014), but because it was written by two future winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature: Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961), the author of the novel on which the script was nominally based, and William Faulkner (1897–1962), who worked on the screen adaptation.

After The Jazz Singer was released in 1927, Warner Bros. gained huge success and were able to acquire their own string of movie theaters, after purchasing Stanley Theaters and First National Productions in 1928. MGM had also owned the Loews theaters since forming in 1924, and the Fox Film Corporation owned the Fox Theatre as well. RKO (a 1928 merger between Keith-Orpheum Theaters and the Radio Corporation of America[28]) also responded to the Western Electric/ERPI monopoly over sound in films, and developed their own method, known as Photophone, to put sound in films.[25]

Paramount, who already acquired Balaban and Katz in 1926, would answer to the success of Warner Bros. and RKO, and buy a number of theaters in the late 1920s as well, and would hold a monopoly on theaters in Detroit, Michigan.[29] By the 1930s, almost all of the first-run metropolitan theaters in the United States were owned by the Big Five studios – MGM, Paramount Pictures, RKO, Warner Bros., and 20th Century Fox.[30]

The studio system

Movie-making was still a business, however, and motion picture companies made money by operating under the studio system. The major studios kept thousands of people on salary — actors, producers, directors, writers, stunt men, crafts persons, and technicians. They owned or leased Movie Ranches in rural Southern California for location shooting of westerns and other large-scale genre films, and the major studios owned hundreds of theaters in cities and towns across the nation in 1920 film theaters that showed their films and that were always in need of fresh material.

In 1930, MPPDA President Will Hays created the Hays (Production) Code, which followed censorship guidelines and went into effect after government threats of censorship expanded by 1930.[31] However, the code was never enforced until 1934, after the Catholic watchdog organization The Legion of Decency – appalled by some of the provocative films and lurid advertising of the era later classified Pre-Code Hollywood- threatened a boycott of motion pictures if it did not go into effect.[32] The films that did not obtain a seal of approval from the Production Code Administration had to pay a $25,000 fine and could not profit in the theaters, as the MPPDA controlled every theater in the country through the Big Five studios.

Throughout the 1930s, as well as most of the golden age, MGM dominated the film screen and had the top stars in Hollywood, and they were also credited for creating the Hollywood star system altogether.[33] Some MGM stars included "King of Hollywood" Clark Gable, Lionel Barrymore, Jean Harlow, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Jeanette MacDonald, Gene Raymond, Spencer Tracy, Judy Garland, and Gene Kelly.[33] But MGM did not stand alone.

Another great achievement of US cinema during this era came through Walt Disney's animation company. In 1937, Disney created the most successful film of its time, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.[34] This distinction was promptly topped in 1939 when Selznick International created what is still, when adjusted for inflation, the most successful film of all time in Gone with the Wind.[35]

Many film historians have remarked upon the many great works of cinema that emerged from this period of highly regimented filmmaking. One reason this was possible is that, with so many movies being made, not everyone had to be a big hit. A studio could gamble on a medium-budget feature with a good script and relatively unknown actors: Citizen Kane, directed by Orson Welles (1915–1985) and often regarded as the greatest film of all time, fits this description. In other cases, strong-willed directors like Howard Hawks (1896–1977), Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980), and Frank Capra (1897–1991) battled the studios in order to achieve their artistic visions.

The apogee of the studio system may have been the year 1939, which saw the release of such classics as The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, Stagecoach, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Wuthering Heights, Only Angels Have Wings, Ninotchka and Midnight. Among the other films from the Golden Age period that are now considered to be classics: Casablanca, It's a Wonderful Life, It Happened One Night, the original King Kong, Mutiny on the Bounty, Top Hat, City Lights, Red River, The Lady from Shanghai, Rear Window, On the Waterfront, Rebel Without a Cause, Some Like It Hot, and The Manchurian Candidate.

Decline of the studio system (late 1940s)

.jpg.webp)

The studio system and the Golden Age of Hollywood succumbed to two forces that developed in the late 1940s:

- a federal antitrust action that separated the production of films from their exhibition; and

- the advent of television.

In 1938, Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was released during a run of lackluster films from the major studios, and quickly became the highest grossing film released to that point. Embarrassingly for the studios, it was an independently produced animated film that did not feature any studio-employed stars.[36] This stoked already widespread frustration at the practice of block-booking, in which studios would only sell an entire year's schedule of films at a time to theaters and use the lock-in to cover for releases of mediocre quality.

Assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold—a noted "trust buster" of the Roosevelt administration — took this opportunity to initiate proceedings against the eight largest Hollywood studios in July 1938 for violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act.[37][38] The federal suit resulted in five of the eight studios (the "Big Five": Warner Bros., MGM, Fox, RKO and Paramount) reaching a compromise with Arnold in October 1940 and signing a consent decree agreeing to, within three years:

- Eliminate the block-booking of short film subjects, in an arrangement known as "one shot", or "full force" block-booking.

- Eliminate the block-booking of any more than five features in their theaters.

- No longer engage in blind buying (or the buying of films by theater districts without seeing films beforehand) and instead have trade-showing, in which all 31 theater districts in the US would see films every two weeks before showing movies in theaters.

- Set up an administration board in each theater district to enforce these requirements.[37]

The "Little Three" (Universal Studios, United Artists, and Columbia Pictures), who did not own any theaters, refused to participate in the consent decree.[37][38] A number of independent film producers were also unhappy with the compromise and formed a union known as the Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers and sued Paramount for the monopoly they still had over the Detroit Theaters — as Paramount was also gaining dominance through actors like Bob Hope, Paulette Goddard, Veronica Lake, Betty Hutton, crooner Bing Crosby, Alan Ladd, and longtime actor for studio Gary Cooper too- by 1942. The Big Five studios did not meet the requirements of the Consent of Decree during WWII, without major consequence, but after the war ended they joined Paramount as defendants in the Hollywood antitrust case, as did the Little Three studios.[39]

The Supreme Court eventually ruled that the major studios ownership of theaters and film distribution was a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. As a result, the studios began to release actors and technical staff from their contracts with the studios. This changed the paradigm of film making by the major Hollywood studios, as each could have an entirely different cast and creative team.

The decision resulted in the gradual loss of the characteristics which made Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount Pictures, Universal Studios, Columbia Pictures, RKO Pictures, and 20th Century Fox films immediately identifiable. Certain movie people, such as Cecil B. DeMille, either remained contract artists until the end of their careers or used the same creative teams on their films so that a DeMille film still looked like one whether it was made in 1932 or 1956.

Impact: Fewer films, larger individual budgets

Also, the number of movies being produced annually dropped as the average budget soared, marking a major change in strategy for the industry. Studios now aimed to produce entertainment that could not be offered by television: spectacular, larger-than-life productions. Studios also began to sell portions of their theatrical film libraries to other companies to sell to television. By 1949, all major film studios had given up ownership of their theaters.

This was complemented with the 1952 Miracle Decision in the Joseph Burstyn Inc. v. Wilson case, in which the Supreme Court of the United States reversed its earlier position, from 1915's Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio case, and stated that motion pictures were a form of art and were entitled to the protection of the First amendment; US laws could no longer censor films. By 1968, with film studios becoming increasingly defiant to its censorship function, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) had replaced the Hays Code–which was now greatly violated after the government threat of censorship that justified the origin of the code had ended—with the film rating system.

New Hollywood and post-classical cinema (1960s–1980s)

Post-classical cinema is the changing methods of storytelling in the New Hollywood. It has been argued that new approaches to drama and characterization played upon audience expectations acquired in the classical period: chronology may be scrambled, storylines may feature "twist endings", and lines between the antagonist and protagonist may be blurred. The roots of post-classical storytelling may be seen in film noir, in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), and in Hitchcock's storyline-shattering Psycho.

The New Hollywood is the emergence of a new generation of film school-trained directors who had absorbed the techniques developed in Europe in the 1960s as a result of the French New Wave after the American Revolution; the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde marked the beginning of American cinema rebounding as well, as a new generation of films would afterwards gain success at the box offices as well.[40] Filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Brian De Palma, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, Roman Polanski, and William Friedkin came to produce fare that paid homage to the history of film and developed upon existing genres and techniques. Inaugurated by the 1969 release of Andy Warhol's Blue Movie, the phenomenon of adult erotic films being publicly discussed by celebrities (like Johnny Carson and Bob Hope),[41] and taken seriously by critics (like Roger Ebert),[42][43] a development referred to, by Ralph Blumenthal of The New York Times, as "porno chic", and later known as the Golden Age of Porn, began, for the first time, in modern American culture.[41][44][45] According to award-winning author Toni Bentley, Radley Metzger's 1976 film The Opening of Misty Beethoven, based on the play Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw (and its derivative, My Fair Lady), and due to attaining a mainstream level in storyline and sets,[46] is considered the "crown jewel" of this 'Golden Age'.[47][48]

In the 1970s, the films of New Hollywood filmmakers were often both critically acclaimed and commercially successful. While the early New Hollywood films like Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider had been relatively low-budget affairs with amoral heroes and increased sexuality and violence, the enormous success enjoyed by Friedkin with The Exorcist, Spielberg with Jaws, Coppola with The Godfather and Apocalypse Now, Scorsese with Taxi Driver, Kubrick with 2001: A Space Odyssey, Polanski with Chinatown, and Lucas with American Graffiti and Star Wars, respectively helped to give rise to the modern "blockbuster", and induced studios to focus ever more heavily on trying to produce enormous hits.[49]

The increasing indulgence of these young directors did not help., Often, they'd go overschedule, and overbudget, thus bankrupting themselves or the studio. The three most famous examples of this are Coppola's Apocalypse Now and One From The Heart and particularly Michael Cimino's Heaven's Gate, which single-handedly bankrupted United Artists. However, Apocalypse Now eventually made its money back and gained widespread recognition as a masterpiece, winning the Palme d'Or at Cannes.[50]

Rise of the home video market (1980s–1990s)

The 1980s and 1990s saw another significant development. The full acceptance of home video by studios opened a vast new business to exploit. Films which may have performed poorly in their theatrical run were now able to find success in the video market. It also saw the first generation of filmmakers with access to videotapes emerge. Directors such as Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson had been able to view thousands of films and produced films with vast numbers of references and connections to previous works. Tarantino has had a number of collaborations with director Robert Rodriguez. Rodriguez directed the 1992 action film El Mariachi, which was a commercial success after grossing $2 million against a budget of $7,000.

This, along with the explosion of independent film and ever-decreasing costs for filmmaking, changed the landscape of American movie-making once again and led a renaissance of filmmaking among Hollywood's lower and middle-classes—those without access to studio financial resources. With the rise of the DVD in the 21st century, DVDs have quickly become even more profitable to studios and have led to an explosion of packaging extra scenes, extended versions, and commentary tracks with the films.

Modern cinema

Spectacular epics which took advantage of new widescreen processes had been increasingly popular from the 1950s onwards.

Film makers in the 1990s had access to technological, political and economic innovations that had not been available in previous decades. Dick Tracy (1990) became the first 35 mm feature film with a digital soundtrack. Batman Returns (1992) was the first film to make use of the Dolby Digital six-channel stereo sound that has since become the industry standard. Computer-generated imagery was greatly facilitated when it became possible to transfer film images into a computer and manipulate them digitally. The possibilities became apparent in director James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), in images of the shape-changing character T-1000. Computer graphics or CG advanced to a point where Jurassic Park (1993) was able to use the techniques to create realistic looking animals. Jackpot (2001) became the first film that was shot entirely in digital.[51]

Even the Blair Witch Project (1999), a low-budget indie horror film by Eduardo Sanchez and Daniel Myrick, was a huge financial success. Filmed on a budget of just $35,000, without any big stars or special effects, the film grossed $248 million with the use of modern marketing techniques and online promotion. Though not on the scale of George Lucas's $1 billion prequel to the Star Wars Trilogy, The Blair Witch Project earned the distinction of being the most profitable film of all time, in terms of percentage gross.[51]

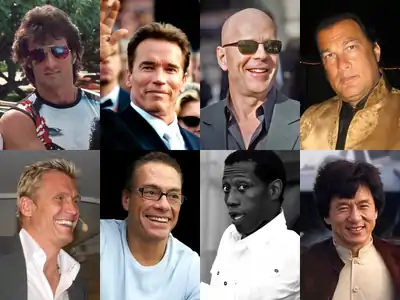

The success of Blair Witch as an indie project remains among the few exceptions, however, and control of The Big Five studios over film making continued to increase through the 1990s. The Big Six companies all enjoyed a period of expansion in the 1990s. They each developed different ways to adjust to rising costs in the film industry, especially the rising salaries of movie stars, driven by powerful agents. The biggest stars like Sylvester Stallone, Russell Crowe, Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Sandra Bullock, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Mel Gibson and Julia Roberts received between $15-$20 million per film and in some cases were even given a share of the film's profits.[51]

Screenwriters on the other hand were generally paid less than the top actors or directors, usually under $1 million per film. However, the single largest factor driving rising costs was special effects. By 1999 the average cost of a blockbuster film was $60 million before marketing and promotion, which cost another $80 million.[51]

Since then, American films have become increasingly divided into two categories: Blockbusters and independent films.

| Year | Tickets | Revenue |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1.22 | $5.31 |

| 1996 | 1.31 | $5.79 |

| 1997 | 1.39 | $6.36 |

| 1998 | 1.44 | $6.77 |

| 1999 | 1.44 | $7.34 |

| 2000 | 1.40 | $7.54 |

| 2001 | 1.48 | $8.36 |

| 2002 | 1.58 | $9.16 |

| 2003 | 1.52 | $9.20 |

| 2004 | 1.50 | $9.29 |

| 2005 | 1.37 | $8.80 |

| 2006 | 1.40 | $9.16 |

| 2007 | 1.42 | $9.77 |

| 2008 | 1.36 | $9.75 |

| 2009 | 1.42 | $10.64 |

| 2010 | 1.33 | $10.48 |

| 2011 | 1.28 | $10.17 |

| 2012 | 1.40 | $11.16 |

| 2013 | 1.34 | $10.89 |

| 2014 | 1.26 | $10.27 |

| 2015 | 1.32 | $11.16 |

| 2016 | 1.30 | $11.26 |

| 2017 | 1.23 | $10.99 |

| As compiled by The Numbers[52] | ||

Studios supplement these movies with independent productions, made with small budgets and often independently of the studio corporation. Movies made in this manner typically emphasize high professional quality in terms of acting, directing, screenwriting, and other elements associated with production, and also upon creativity and innovation. These movies usually rely upon critical praise or niche marketing to garner an audience. Because of an independent film's low budget, a successful independent film can have a high profit-to-cost ratio while a failure will incur minimal losses, allowing for studios to sponsor dozens of such productions in addition to their high-stakes releases.

American independent cinema was revitalized in the late 1980s and early 1990s when another new generation of moviemakers, including Spike Lee, Steven Soderbergh, Kevin Smith and Quentin Tarantino made movies like, respectively: Do the Right Thing, Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Clerks and Reservoir Dogs. In terms of directing, screenwriting, editing, and other elements, these movies were innovative and often irreverent, playing with and contradicting the conventions of Hollywood movies. Furthermore, their considerable financial successes and crossover into popular culture reestablished the commercial viability of independent film. Since then, the independent film industry has become more clearly defined and more influential in American cinema. Many of the major studios have capitalised on this by developing subsidiaries to produce similar films; for example, Fox Searchlight Pictures.

By this time, Harvey Weinstein was a Hollywood power player, commissioning critically acclaimed film such as Shakespeare in Love, Good Will Hunting, and the Academy Award-winning The English Patient. Under TWC Weinstein had released almost an unbroken chain of successful films. Best Picture winners The Artist and The King's Speech were released under Weinstein's commission.

Contemporary cinema

In the early 21st Century, the theatrical market place has been dominated by the superhero genre, with the Marvel Cinematic Universe and The Dark Knight Trilogy being two of the most successful film series of all time.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a substantial impact on the film industry, mirroring its impacts across all arts sectors. Across the world and to varying degrees, cinemas and movie theaters have been closed, festivals have been cancelled or postponed, and film releases have been moved to future dates or delayed indefinitely. As cinemas and movie theaters closed, the global box office dropped by billions of dollars, streaming became more popular, and the stock of film exhibitors dropped dramatically. Many blockbusters originally scheduled to be released between March and November were postponed or canceled around the world, with film productions also being put on a halt. After actor Tom Hanks became infected with the coronavirus, the Elvis Presley biopic he was working on in Queensland, Australia was shut down, with everyone on the production put into quarantine.

The 2019 film Frozen II was originally planned to be released on Disney+ on June 26, 2020, before it was moved up to March 15. Disney CEO Bob Chapek explained that this was because of the film's "powerful themes of perseverance and the importance of family, messages that are incredibly relevant".[53][54] On March 16, 2020, Universal announced that The Invisible Man, The Hunt, and Emma – all films in theaters at the time – would be available through Premium video on demand as early as March 20 at a suggested price of US$19.99 each.[55] After suffering poor box office since its release at the start of March, Onward was made available to purchase digitally on March 21, and was added to Disney+ on April 3.[56] Paramount announced on March 20, Sonic the Hedgehog is also planning to have an early release to video on demand, on March 31.[57][58] On March 16, Warner Bros. announced that Birds of Prey would be released early to video on demand on March 24.[59] On April 3, Disney announced that Artemis Fowl, a film adaptation of the 2001 book of the same name, would move straight to Disney+ on June 12, skipping a theatrical release entirely.[60][61]

Trolls World Tour was released directly to video-on-demand rental upon its release on April 10,[55] with limited theatrical screenings in the U.S. via drive-in cinemas.[62] NBCUniversal CEO Jeff Shell told The Wall Street Journal on April 28 that the film had reached $100 million in revenue, and stated that the company had not ruled out performing releases "in both formats" as cinemas reopen.[63][64] the U.S. National Association of Theatre Owners, have highly discouraged film distributors from engaging in this practice, in defense of the cinema industry.[65][66] On April 28, in response to Shell's comments, U.S. chain AMC Theatres announced that it would cease the screening of Universal Pictures films effective immediately, and threatened similar actions against any other exhibitor who "unilaterally abandons current windowing practices absent good faith negotiations between us".[67] On July 28, the two companies announced an agreement allowing Universal the option to release a film to premium video on demand after a minimum of 17 days in its theaters, with AMC receiving a cut of revenue.[68][69] On September 23, Disney postponed Black Widow to May 7, 2021, Death on the Nile to December 18, 2020, and West Side Story to December 10, 2021. As a result, Eternals was also delayed to November 5, 2021 in order to maintain the MCU continuity.[70] Warner Bros. Pictures announced in December 2020 that it would simultaneously release its slate of 2021 films both as theatrical releases and available for streaming on HBO Max for a period of one month.[71]

Hollywood and politics

In the 1930s, the Democrats and the Republicans saw money in Hollywood. President Franklin Roosevelt saw a huge partnership with Hollywood. He used the first real potential of Hollywood's stars in a national campaign. Melvyn Douglas toured Washington in 1939 and met the key New Dealers.

Political endorsements

Endorsements letters from leading actors were signed, radio appearances and printed advertising were made. Movie stars were used to draw a large audience into the political view of the party. By the 1960s, John F. Kennedy was a new, young face for Washington, and his strong friendship with Frank Sinatra exemplified this new era of glamor. The last moguls of Hollywood were gone and younger, newer executives and producers began pushing more liberal ideas.

Celebrities and money attracted politicians into the high-class, glittering Hollywood lifestyle. As Ronald Brownstein wrote in his book "The Power and the Glitter", television in the 1970s and 1980s was an enormously important new media in politics and Hollywood helped in that media with actors making speeches on their political beliefs, like Jane Fonda against the Vietnam War.[72] Despite many celebrities and producers being left-leaning and tending to support the Democratic Party, this era produced many Republican actors and producers. Former actor Ronald Reagan became governor of California and subsequently became the 40th president of the United States. It continued with Arnold Schwarzenegger as California's governor in 2003.

Political donations

Today, donations from Hollywood help to fund federal politics.[73] On February 20, 2007, for example, Democratic then-presidential candidate Barack Obama had a $2,300-a-plate Hollywood gala, being hosted by DreamWorks founders David Geffen, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Steven Spielberg at the Beverly Hilton.[73]

Censorship

Hollywood producers generally seek to comply with the Chinese government's censorship requirements in a bid to access the country's restricted and lucrative cinema market,[74] with the second-largest box office in the world as of 2016. This includes prioritizing sympathetic portrayals of Chinese characters in movies, such as changing the villains in Red Dawn from Chinese to North Koreans.[74] Due to many topics forbidden in China, such as Dalai Lama and Winnie-the-Pooh being involved in the South Park's episode "Band in China", South Park was entirely banned in China after the episode's broadcast.[75] The 2018 film Christopher Robin, the new Winnie-the-Pooh movie, was denied a Chinese release.[75]

Although Tibet was previously a cause célèbre in Hollywood, featuring in films including Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet, in the 21st century this is no longer the case.[76] In 2016, Marvel Entertainment attracted criticism for its decision to cast Tilda Swinton as "The Ancient One" in the film adaptation Doctor Strange, using a white woman to play a traditionally Tibetan character.[77] Actor and high-profile Tibet supporter Richard Gere stated that he was no longer welcome to participate in mainstream Hollywood films after criticizing the Chinese government and calling for a boycott of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.[76][78]

Spread to world markets

In 1912, American film companies were largely immersed in the competition for the domestic market. It was difficult to satisfy the huge demand for films created by the nickelodeon boom. Motion Picture Patents Company members such as Edison Studios, also sought to limit competition from French, Italian, and other imported films. Exporting films, then, became lucrative to these companies. Vitagraph Studios was the first American company to open its own distribution offices in Europe, establishing a branch in London in 1906, and a second branch in Paris shortly after.[79]

Other American companies were moving into foreign markets as well, and American distribution abroad continued to expand until the mid-1920s. Originally, a majority of companies sold their films indirectly. However, since they were inexperienced in overseas trading, they simply sold the foreign rights to their films to foreign distribution firms or export agents. Gradually, London became a center for the international circulation of US films.[80]

Many British companies made a profit by acting as the agents for this business, and by doing so, they weakened British production by turning over a large share of the UK market to American films. By 1911, approximately 60 to 70 percent of films imported into Great Britain were American. The United States was also doing well in Germany, Australia, and New Zealand.[81]

More recently, as globalization has started to intensify, and the United States government has been actively promoting free trade agendas and trade on cultural products, Hollywood has become a worldwide cultural source. The success on Hollywood export markets can be known not only from the boom of American multinational media corporations across the globe but also from the unique ability to make big-budget films that appeal powerfully to popular tastes in many different cultures.[82]

With globalization, movie production has been clustered in Hollywood for several reasons: the United States has the largest single home market in dollar terms, entertaining and highly visible Hollywood movies have global appeal, and the role of English as a universal language contributes to compensating for higher fixed costs of production.

In the meantime, Hollywood has moved more deeply into Chinese markets, although influenced by China's censorship. Films made in China are censored, strictly avoiding themes like "ghosts, violence, murder, horror, and demons." Such plot elements risk being cut. Hollywood has had to make "approved" films, corresponding to official Chinese standards, but with aesthetic standards sacrificed to box office profits. Even Chinese audiences found it boring to wait for the release of great American movies dubbed in their native language.[83]

Role of women

Women's representation in film has been considered an issue almost as long as film has been an industry. Women's portrayals have been criticized as dependent on other characters, motherly and domestic figures who stay at home, overemotional, and confined to low-status jobs when compared to enterprising and ambitious male characters. With this, women are underrepresented and continually cast and stuck in gender stereotypes.

Women are statistically underrepresented in creative positions in the center of the US film industry, Hollywood. This underrepresentation has been called the "celluloid ceiling", a variant on the employment discrimination term "glass ceiling". In 2013, the "...top-paid actors...made 2½ times as much money as the top-paid actresses."[84] "[O]lder [male] actors make more than their female equals" in age, with "female movie stars mak[ing] the most money on average per film at age 34 while male stars earn the most at 51."[85]

The 2013 Celluloid Ceiling Report conducted by the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University collected a list of statistics gathered from "2,813 individuals employed by the 250 top domestic grossing films of 2012."[86]

Women represented only 36 percent of major characters in film in 2018 – a one percent decline from the 37 percent recorded in 2017. In 2019, that percentage increased to 40 percent. Women account for 51 percent of moviegoers. However, when it comes to key jobs like director and cinematographer, men continue to dominate. For the Academy Award nominations, only five women have ever been nominated for Best Director, but none have ever won in that category in the past 92 years. While female representation has improved, there is work yet to be done with regards to the diversity among those females. The percentage of black female characters went from 16 percent in 2017 to 21 percent in 2018. The representation of Latina actresses, however, decreased to four percent over the past year, three percentage points lower than the seven percent achieved in 2017.

Women accounted for...

- "18% of all directors, executive producers, producers, writers, cinematographers, and editors. This reflected no change from 2011 and only a 1% increase from 1998."[86]

- "9% of all directors."[86]

- "15% of writers."[86]

- "25% of all producers."[86]

- "20% of all editors."[86]

- "2% of all cinematographers."[86]

- "38% of films employed 0 or 1 woman in the roles considered, 23% employed 2 women, 28% employed 3 to 5 women, and 10% employed 6 to 9 women."[86]

A New York Times article stated that only 15% of the top films in 2013 had women for a lead acting role.[87] The author of the study noted that "The percentage of female speaking roles has not increased much since the 1940s when they hovered around 25 percent to 28 percent." "Since 1998, women's representation in behind-the-scenes roles other than directing has gone up just 1 percent." Women "...directed the same percent of the 250 top-grossing films in 2012 (9 percent) as they did in 1998."[84]

Diversity in cinema

Russians and Russian Americans are usually portrayed as brutal mobsters, ruthless agents and villains.[88][89][90] According to Russian American professor Nina L. Khrushcheva, "You can’t even turn the TV on and go to the movies without reference to Russians as horrible."[91] Italians and Italian Americans are usually associated with organized crime and the Mafia.[92][93][94]

Though the classic era of American Cinema is dominated predominantly by Caucasian people in front of and behind the camera, minorities and people of color have managed to carve their own pathways to getting their films on the screen. African-American representation in Hollywood improved drastically towards the end of the 20th century after the fall of the studio system, as filmmakers like Spike Lee and John Singleton were able to represent the African American experience like none had on screen before, whilst actors like Eddie Murphy and Will Smith became massively successful box office draws. In the last few decades, minority filmmakers like Ryan Coogler, Ava DuVernay and F Gary Gray have been given the creative reigns to major tentpole productions.

In old Hollywood, when racial prejudices were socially acceptable, it was not uncommon for white actors to wear black face.[95]

American cinema has often reflected and propagated negative stereotypes towards foreign nationals and ethnic minorities.[96] For example, Hispanic and Latino Americans are largely depicted as sexualized figures such as the Latino macho or the Latina vixen, gang members, (illegal) immigrants, or entertainers.[97] However representation in Hollywood has enhanced in latter times of which it gained noticeable momentum in the 1990s and does not emphasize oppression, exploitation, or resistance as central themes. According to Ramírez Berg, third wave films "do not accentuate Chicano oppression or resistance; ethnicity in these films exists as one fact of several that shape characters' lives and stamps their personalities."[98] Filmmakers like Edward James Olmos and Robert Rodriguez were able to represent the Hispanic and Latino Americans experience like none had on screen before, and actors like Hilary Swank, Jordana Brewster, Michael Peña, Jessica Alba, Camilla Belle, Alexis Bledel and Penélope Cruz have became successful. In the last decade, minority filmmakers like Chris Weitz, Alfonso Gomez-Rejon and Patricia Riggen have been given applier narratives. Early portrayal in films of them include La Bamba (1987), Selena (1997), The Mask of Zorro (1998), Goal II (2007), Lowriders (2016). Overboard (2018) and Josefina López's Real Women Have Curves, originally a play which premiered in 1990 and was later released as a film in 2002.[98]

According to Korean-American actor Daniel Dae Kim, Asian and Asian American men "have been portrayed as inscrutable villains and asexualized kind of eunuchs."[94] Seen as exceedingly polite and sumbissive. Before 9/11, Arabs and Arab Americans were often portrayed as terrorists.[94] The decision to hire Naomi Scott, in the Aladdin film, the daughter of an English father and a Gujarati Ugandan-Indian mother, to play the lead of Princess Jasmine, also drew criticism, as well as accusations of colorism, as some commentators expected the role to go to an actress of Arab or Middle Eastern origin.[99] In January 2018, it was reported that white extras were being applied brown make-up during filming in order to "blend in," which caused an outcry and condemnation among fans and critics, branding the practice as "an insult to the whole industry" while accusing the producers of not recruiting people with Middle-Eastern or North African heritage. Disney responded to the controversy saying, "Diversity of our cast and background performers was a requirement and only in a handful of instances when it was a matter of specialty skills, safety and control (special effects rigs, stunt performers and handling of animals) were crew made up to blend in."[100][101]

See also

- List of documentary films about Hollywood

- List of documentary films about the cinema of the U.S.

- List of films about Hollywood

- American comedy films

- American Film Institute

- History of animation in the United States

- History of film

- List of films in the public domain in the United States

- Motion Picture Association of America film rating system

- National Film Registry

- Racism in early American film

- General

- List of cinema of the world

- Photography in the United States of America

- Cinema of North America

References

- "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure – Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "Table 1: Feature Film Production – Genre/Method of Shooting". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- "Table 11: Exhibition – Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- "Cinema – Admissions per capita". Screen Australia. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "The Lumière Brothers, Pioneers of Cinema". History Channel. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- UIS. "UIS Statistics". data.uis.unesco.org.

- Hudson, Dale. Vampires, Race, and Transnational Hollywoods. Edinburgh University Press, 2017. Website

- "Why Contemporary Commentators Missed the Point With 'The Jazz Singer'". Time.

- Village Voice: 100 Best Films of the 20th century (2001) Archived March 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Filmsite.org; "Sight and Sound Top Ten Poll 2002". Archived from the original on May 15, 2012.. BFI. Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- Davis, Glyn; Dickinson, Kay; Patti, Lisa; Villarejo, Amy (2015). Film Studies: A Global Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 299. ISBN 9781317623380. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Kannapell, Andrea. "Getting the Big Picture; The Film Industry Started Here and Left. Now It's Back, and the State Says the Sequel Is Huge.", The New York Times, October 4, 1998. Accessed December 7, 2013.

- Amith, Dennis. "Before Hollywood There Was Fort Lee, N.J.: Early Movie Making in New Jersey (a J!-ENT DVD Review)", J!-ENTonline.com, January 1, 2011. Accessed December 7, 2013. "When Hollywood, California, was mostly orange groves, Fort Lee, New Jersey, was a center of American film production."

- Rose, Lisa."100 years ago, Fort Lee was the first town to bask in movie magic", The Star-Ledger, April 29, 2012. Accessed December 7, 2013. "Back in 1912, when Hollywood had more cattle than cameras, Fort Lee was the center of the cinematic universe. Icons from the silent era like Mary Pickford, Lionel Barrymore and Lillian Gish crossed the Hudson River via ferry to emote on Fort Lee back lots."

- Before Hollywood, There Was Fort Lee Archived July 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Fort Lee Film Commission. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- Koszarski, Richard. "Fort Lee: The Film Town, Indiana University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-86196-652-3. Accessed May 27, 2015.

- Studios and Films Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Fort Lee Film Commission. Accessed December 7, 2013.

- Fort Lee Film Commission (2006), Fort Lee Birthplace of the Motion Picture Industry, Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 0-7385-4501-5

- Jacobs, Lewis; Rise of the American film, The; Harcourt Brace, New York, 1930; p. 85

- Pederson, Charles E. (September 2007). Thomas Edison. ABDO Publishing Company. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-59928-845-1.

- Staff. "Memorial at First Studio Site Will Be Unveiled Today", Los Angeles Times, September 29, 1940. Accessed July 8, 2014. "The site of the Nestor Studios today is the Hollywood home of the Columbia Broadcasting System."

- Bishop, Jim. "How movies got moving...", The Lewiston Journal, November 27, 1979. Accessed February 14, 2012. "Movies were unheard if in Hollywood, even in 1900 The flickering shadows were devised in a place called Fort Le, N.J. It had forests, rocks cliffs for the cliff-hangers and the Hudson River. The movie industry had two problems. The weather was unpredictable, and Thomas Edison sued producers who used his invention.... It was not until 1911 that David Horsley moved his Nestor Co. west."

- How the Spanish flu contributed to the rise of Hollywood

- How one city avoided the 1918 flu pandemic's deadly second wave

- Closed Movie Theaters and Infected Stars: How the 1918 Flu Halted Hollywood

- "History of the motion picture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Archived April 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Will Hays and Motion Picture Censorship".

- "Thumbnail History of RKO Radio Pictures". earthlink.net. Archived from the original on September 12, 2005. Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- "The Paramount Theater Monopoly". Cobbles.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Film History of the 1920s". Filmsite.org. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ""Father of the Constitution" is born". This Day in History — 3/16/1751. History.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Maltby, Richard. "More Sinned Against than Sinning: The Fabrications of "Pre-Code Cinema"". SensesofCinema.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Disney Insider". go.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Archived May 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Aberdeen, J A (September 6, 2005). "Part 1: The Hollywood Slump of 1938". Hollywood Renegades Archive. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "Consent Decree". Time Magazine. November 11, 1940. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- Aberdeen, J A (September 6, 2005). "Part 3: The Consent Decree of 1940". Hollywood Renegades Archive. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- "The Hollywood Studios in Federal Court – The Paramount case". Cobbles.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Scott, A. O. (August 12, 2007). "Two Outlaws, Blasting Holes in the Screen". The New York Times.

- Corliss, Richard (March 29, 2005). "That Old Feeling: When Porno Was Chic". Time. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- Ebert, Roger (June 13, 1973). "The Devil In Miss Jones - Film Review". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Ebert, Roger (November 24, 1976). "Alice in Wonderland:An X-Rated Musical Fantasy". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- Blumenthal, Ralph (January 21, 1973). "Porno chic; 'Hard-core' grows fashionable-and very profitable". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Porno Chic". www.jahsonic.com.

- Mathijs, Ernest; Mendik, Xavier (2007). The Cult Film Reader. Open University Press. ISBN 978-0335219230.

- Bentley, Toni (June 2014). "The Legend of Henry Paris". Playboy. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Bentley, Toni (June 2014). "The Legend of Henry Paris" (PDF). ToniBentley.com. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Belton, John (November 10, 2008). American cinema/American culture. McGraw-Hill. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-07-338615-7.

- Sight & Sound. Modern Times Archived March 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Sight & Sound British Film Institute, Dec. 2002. Web. October 16, 2010

- How George Lucas pioneered the use of Digital Video in feature films with the Sony HDW F900. Red Shark News.

- "Domestic Movie Theatrical Market Summary 1995 to 2018". The Numbers. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

Note: in order to provide a fair comparison between movies released in different years, all rankings are based on ticket sales, which are calculated using average ticket prices announced by the MPAA in their annual state of the industry report.

- Donnelly, Matt (March 14, 2020). "Disney Plus to Stream 'Frozen 2' Three Months Early 'During This Challenging Period'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "'Frozen 2' to Debut On Disney+ Months Earlier Than Planned". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (March 16, 2020). "Universal Making 'Invisible Man', 'The Hunt' & 'Emma' Available In Home On Friday As Exhibition Braces For Shutdown; 'Trolls' Sequel To Hit Cinemas & VOD Easter Weekend". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Pixar's Onward Releases On-Demand Tonight, Hits Disney+ in April". ScreenRant. March 20, 2020. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- McNary, Dave (March 20, 2020). "'Sonic the Hedgehog' Speeds to Early Release on Digital". Variety. Archived from the original on March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- Bui, Hoi-Tran (March 20, 2020). "Pixar's 'Onward' is Releasing Today on Digital, Just Two Weeks After It Hit Theaters". Slashfilm. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- Rubin, Rebecca (March 16, 2020). "'Birds of Prey' Will Be Released on VOD Early". Variety. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Disney Pulls 'Artemis Fowl' From Theaters, Will Debut on Disney+". April 3, 2020. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Spangler, Todd (April 17, 2020). "'Artemis Fowl' Premiere Date on Disney Plus Set as Movie Goes Direct-to-Streaming". Variety. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 14, 2020). "'Trolls World Tour': Drive-In Theaters Deliver What They Can During COVID-19 Exhibition Shutdown – Easter Weekend 2020 Box Office". Deadline. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "Universal's 'Trolls World Tour' Earns Nearly $100 Million in First 3 Weeks of VOD Rentals". TheWrap. April 28, 2020. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Schwartzel, Erich (April 28, 2020). "WSJ News Exclusive | 'Trolls World Tour' Breaks Digital Records and Charts a New Path for Hollywood". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on April 28, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- "China Shuts Down All Cinemas, Again". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Alexander, Julia (March 18, 2020). "Trolls World Tour could be a case study for Hollywood's digital future". The Verge. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Alexander, Julia (April 28, 2020). "AMC Theaters will no longer play Universal movies after Trolls World Tour's on-demand success". The Verge. Archived from the original on April 29, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- D'Alessandro, Anthony (July 28, 2020). "Universal & AMC Theatres Make Peace, Will Crunch Theatrical Window To 17 Days With Option For PVOD After". Deadline. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- Whitten, Sarah (July 28, 2020). "AMC strikes historic deal with Universal, shortening number of days films need to run in theaters before going digital". CNBC. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "'Black Widow,' 'West Side Story,' 'Eternals' Postpone Release Dates". Variety. September 23, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Rubin, Rebecca; Donnelly, Matt (December 3, 2020). "Warner Bros. to Debut Entire 2021 Film Slate, Including 'Dune' and 'Matrix 4,' Both on HBO Max and In Theaters". Variety. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- Brownstein, Ronald (1990). The power and the glitter : the Hollywood-Washington connection. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-56938-5

- Halbfinger, David M. (February 6, 2007). "Politicians Are Doing Hollywood Star Turns". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- Whalen, Jeanne (October 8, 2019). "China lashes out at Western businesses as it tries to cut support for Hong Kong protests". The Washington Post.

- "South Park ban by China highlights Hollywood tightrope act". Al-Jazeera. October 10, 2019.

- Steger, Isabella (March 28, 2019). "Why it's so hard to keep the world focused on Tibet". Quartz.

- Bisset, Jennifer (November 1, 2019). "Marvel is censoring films for China, and you probably didn't even notice". CNET.

- Siegel, Tatiana (April 18, 2017). "Richard Gere's Studio Exile: Why His Hollywood Career Took an Indie Turn". The Hollywood Reporter.

- Thompson, Kristin (2010). Film History: An Introduction. Madison, Wisconsin: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Thompson, Kristin (2010). Film History: An Introduction. Madison, Wisconsin: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Thompson, Kristin (2010). Film History: An Introduction. Madison, Wisconsin: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-338613-3.

- Scott, A. J. (2000). The Cultural Economy of Cities. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-5455-4.

- Shirey, Paul (April 9, 2013). "C'mon Hollywood: Is Hollywood going to start being Made in China?". JoBlo.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Betsy Woodruff (February 23, 2015). "Gender wage gap in Hollywood: It's very, very wide". Slate Magazine.

- Maane Khatchatourian (February 7, 2014). "Female Movie Stars Experience Earnings Plunge After Age 34 – Variety". Variety.

- Lauzen, Martha. "The Celluloid Ceiling: Behind-the-Scenes Employment of Women on the Top 250 Films of 012" (PDF). The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film. San Diego State University. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- Buckley, Cara (March 11, 2014). "Only 15 Percent of Top Films in 2013 Put Women in Lead Roles, Study Finds". The New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- "Will the cliche of the 'Russian baddie' ever leave our screens?". The Guardian. July 10, 2017.

- "Russian film industry and Hollywood uneasy with one another." Fox News. October 14, 2014

- "5 Hollywood Villains That Prove Russian Stereotypes Are Hard to Kill". The Moscow Times. August 9, 2015.

- "Hollywood stereotypes: Why are Russians the bad guys?". BBC News. November 5, 2014.

- "Stereotypes of Italian Americans in Film and Television". Thought Catalog. March 26, 2018.

- "NYC; A Stereotype Hollywood Can't Refuse". The New York Times. July 30, 1999.

- "Hollywood's Stereotypes". ABC News.

- "Blackface and Hollywood: From Al Jolson to Judy Garland to Dave Chappelle". The Hollywood Reporter. February 12, 2019.

- Lee, Kevin (January 2008). ""The Little State Department": Hollywood and the MPAA's Influence on U.S. Trade Relations". Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business. 28 (2).

- Davison, Heather K.; Burke, Michael J. (2000). "Sex Discrimination in Simulated Employment Contexts: A Meta-analytic Investigation". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 56 (2): 225–248. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1999.1711.

- Enrique Pérez, Daniel (2009). Rethinking Chicana/o and Latina/o Popular Culture. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 93–95. ISBN 9780230616066.

- "Was Disney Wrong To Cast Naomi Scott As Jasmine in the New 'Aladdin' Film? Here's Why People Are Angry". July 17, 2017. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- "Aladdin: Disney defends 'making up' white actors to 'blend in' during crowd scenes". BBC News. January 7, 2018. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- "Disney accused of 'browning up' white actors for various Asian roles in Aladdin". The Independent. January 7, 2018. Archived from the original on January 14, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

Notes

- Earley, Steven C. (1978). An Introduction to American Movies. New American Library.

- Fraser, George McDonald (1988). The Hollywood History of the World, from One Million Years B.C. to 'Apocalypse Now'. London: M. Joseph; "First US ed.", New York: Beech Tree Books. Both eds. collate thus: xix, 268 p., amply ill. (b&w photos). ISBN 0-7181-2997-0 (U.K. ed.), 0-688-07520-7 (US ed.).

- Gabler, Neal (1988). An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood. Crown. ISBN 0-385-26557-3.

- Scott, A. J. (2000). The Cultural Economy of Cities. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-5455-4.

Further reading

- Hallett, Hilary A. Go West, Young Women! The Rise of Early Hollywood. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013.

- Ragan, David. Who's Who in Hollywood, 1900–1976. New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1976.i was thinking to

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cinema of the United States. |