Hylton Castle

Hylton Castle (/ˈhɪltən/ HIL-tən) is a stone castle in the North Hylton area of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England. Originally built from wood by the Hilton (later Hylton) family shortly after the Norman Conquest in 1066, it was later rebuilt in stone in the late 14th to early 15th century.[1] The castle underwent major changes to its interior and exterior in the 18th century and it remained the principal seat of the Hylton family until the death of the last Baron in 1746.[2] It was then Gothicised but neglected until 1812, when it was revitalised by a new owner. Standing empty again until the 1840s, it was briefly used as a school until it was purchased again in 1862. The site passed to a local coal company in the early 20th century and was taken over by the state in 1950.

| Hylton Castle | |

|---|---|

West façade of Hylton Castle, 2008 | |

Location within Tyne and Wear | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Medieval, Gothic |

| Town or city | Sunderland |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 54.92253°N 1.44318°W |

| Construction started | c. 1390 (from wood to stone) |

| Client | Sir William Hylton |

| Owner | English Heritage |

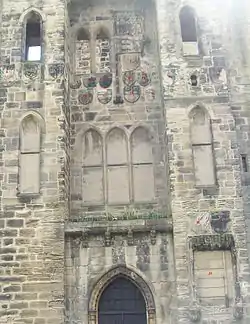

One of the castle's main features is the range of heraldic devices found mainly on the west façade, which have been retained from the castle's original construction. They depict the coats of arms belonging to local gentry and peers of the late 14th to early 15th centuries and provide an approximate date of the castle's reconstruction from wood to stone.

Today, the castle is owned by English Heritage, a charity which manages the historical environment of England. The surrounding parkland is maintained by a community organisation.[3] The castle and its chapel are protected as a Grade I listed building and a Scheduled Ancient Monument. In February, 2016, plans were announced to turn the castle into a community facility and visitor attraction, with the Heritage Lottery Fund awarding £2.9 million, and Sunderland Council £1.5 million, to provide classrooms, a cafe and rooms for exhibitions, meetings and events.[4]

History

Early history

The Hylton family had been settled in England since the reign of King Athelstan (c.895–939).[5][6] At this time, Adam de Hylton gave to the monastery of Hartlepool a pyx or crucifix, weighing 25 ounces (710 g) in silver and emblazoned with his coat of arms – argent, two bars azure.[5][6] On the arrival of William the Conqueror, Lancelot de Hilton and his two sons, Robert and Henry, joined the Conqueror's forces, but Lancelot was killed at Faversham during William's advance to London.[6] In gratitude, the king granted the eldest son, Henry, a large tract of land on the banks of the River Wear.[6]

The first castle on the site, built by Henry de Hilton in about 1072, was likely to have been built of wood. It was subsequently re-built in stone by Sir William Hylton (1376–1435) as a four-storey, gatehouse-style, fortified manor house, similar in design to Lumley and Raby.[1][7] Although called a gatehouse, it belongs to a type of small, late-14th-century castle, similar to Old Wardour, Bywell and Nunney castles.[8] The castle was first mentioned in a household inventory taken in 1448, as "a gatehouse constructed of stone" and although no construction details survive, it is believed the stone castle was built sometime between 1390 and the early 15th century, due to the coat of arms featured above the west entrance (see Heraldry below).[9][10] It has been suggested that Sir William intended to erect a larger castle in addition to the gatehouse, but abandoned his plan.[11]

The household inventory taken on Sir William's death in 1435 mentions, in addition to the castle, a hall, four chambers, two barns, a kitchen, and the chapel, indicating the existence of other buildings on the site at that time.[10] Apart from the castle and chapel, the other buildings were probably all of timber.[9] In 1559, the gatehouse featured in another household inventory as the "Tower", when floors and galleries were inserted to subdivide the great hall.[8][10]

The eccentric Henry Hylton, de jure 12th Baron Hylton left the castle to the City of London Corporation on his death in 1641, to be used for charitable purposes for ninety-nine years.[12] It was returned to the family after the Restoration, to Henry's nephew, John Hylton, de jure 15th Baron Hylton.[3][12]

18th century

Early in the 18th century, John Hylton (died 1712), the second son of Henry Hylton, de jure 16th Baron Hylton, gutted the interior to form a three-storeyed block (one room on each floor).[8] He also inserted large, alternating, pedimented sash windows in the Italianate style and added a three-storeyed north wing to the castle (as seen in Bucks' engraving of 1728).[8] A doorway to the new wing was added and approached by a semi-circular staircase. Above the doorway was a coat of arms, believed to be the one created to commemorate the marriage between John Hylton and his wife, Dorothy Musgrave. It is now located above the doorway to The Golden Lion Inn at South Hylton, on the opposite side of the River Wear.[13][14][15]

After 1728, Hylton's second son, John Hylton, de jure 18th Baron Hylton added a complementary south wing (its foundation wall still extant), crenellations to both wings and removed the door on the north wing.[11][13] He also changed the circular bartizan on the north end of the west front, to an octagonal turret and removed the portcullis from the west entrance.[10]

When the 18th and last "baron" died without male heirs in 1746, the castle passed to his nephew, Sir Richard Musgrave, Bt, who took the name of Hylton. It was sold by a private bill (23 Geo. II c.21) in 1749.[3][10] The new owner was to be a Mr. Wogan who returned from the East Indies to buy the castle for £30,550 (£3.7 million in 2007), but the sale never went through.[16][17] It was instead bought by Lady Bowes, the widow of Sir George Bowes of Streatlam and Gibside in County Durham.[7][16] No record of her, or any of her family, ever taking up residence exists and the castle later passed to her grandson, John Bowes, 10th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne.[7][18] At this time, a stucco decoration (long since disappeared) to the wine and drawing rooms was added by Pietro La Francini, who worked for Daniel Garrett (who had worked for Lady Bowes on Gibside Banqueting House).[8] William Howitt's Visits to Remarkable Places (1842) notes the rooms had "stuccoed ceilings, with figures, busts on the walls, and one large scene which seemed to be Venus and Cupid, Apollo fiddling to the gods, Minerva in her helmet, and an old king".[19] Garrett probably designed the Gothic porch installed in the west entrance and the Gothic screen and single-storey, bow-fronted rooms installed to close off the east entrance.[1][8][19]

19th century

After a long period of remaining empty, the castle slowly began to decay, until in 1812, when Simon Temple, a local businessman, leased the castle from the Strathmores and made it habitable.[1] He re-roofed the chapel (allowing it to be used for public worship again), added battlements to the wings and cultivated the gardens.[1][19] However, his failed business ventures prevented him from completing his work, and in 1819 the castle was lived in by a Mr. Thomas Wade.[1][19]

By 1834, the castle was unoccupied again.[19] In 1840, an advert was placed in the Newcastle Courant by Revd. John Wood for "Hylton Castle Boarding School" and the 1841 census shows Wood, his family, pupils and staff as living on the estate.[20] Joseph Swan was one of the pupils there around this time. The school does not seem to have existed for long as Howitt commented in 1842, that it was "a scene of great desolation ... the windows for the most part, all along the front, are boarded up ... the whole of this large old house is now empty ... and in the most desolate state".[19] However, he does go on to say the kitchen was occupied a poor family.[19] By 1844, the chapel was used as a carpenter's workshop, and according to the Durham Chronicle in January 1856, the castle set on fire while in the occupation of a farmer, Mr. Maclaren.[19][21]

In 1862, the castle was put up for sale by the Strathmores and purchased by William Briggs, a local timber merchant and ship builder.[8][22][23] Briggs set about to change the appearance of the castle to what he believed to be more "authentic[ally] medieval".[8] He demolished the north and south wings, gutted the interior and added one, two and three-light cusp-headed windows.[19] He also replaced the Gothic porch with a more "severe" Gothic doorway (three-bayed with cinquefoil arches) and an overhead balcony.[8] To carry out these changes to the west front, he moved the stone-carved Hylton banner from above the west entrance to the front, left-flanking tower.[8] The interior walls of the four-vaulted ground floor rooms were demolished, the whole floor was raised three-and-a-half feet and two reception rooms were formed.[24] At the east end of the former central passage, dog-leg stairs were constructed leading to the first floor, requiring removal of the oratory and rendering the main staircase inaccessible from the ground floor.[8][24] The side walls of the great hall were removed to create a large salon and a large bay window was added to the south façade, where the entrance to the south wing would have been.[24] The rooms above were kept untouched, except that a new entrance to the family/chaplain's room had to be formed via the main staircase.[24]

Alongside the medieval masonry, Briggs' alterations can still be seen today (albeit in ruins).[8] Briggs' son, Colonel Charles James Briggs (father of Sir Charles James Briggs) inherited the castle in 1871 and built the nearby St Margaret's church (now demolished).[23][25]

20th century

After Colonel Brigg's death in 1900, the castle passed into the hands of the Wearmouth Coal Company about 1908, and from there to the National Coal Board.[23][26] Due to the expansion of Sunderland in the 1940s, the castle became surrounded by housing estates including those of Castletown and Hylton Castle. The castle was vandalised and had the lead from its roof stolen.[23] In 1950, due to local pressure and the threat of demolition, the castle and chapel were taken into the care of the Ministry of Works.[3][10] Due to the advanced decay of the 19th-century alterations, the ministry removed all internal partitions and consolidated the shell to reveal the remaining medieval masonry.[10][27] The ministry also appointed a full-time custodian and replaced the missing lead roof with roofing felt to make the site waterproof.[3]

In 1994, Channel 4's Time Team undertook excavations on the Eastern Terrace. Their investigations revealed evidence of a medieval hall to the east of the castle; it has been suggested that the hall was used as a dining area.[28]

Chapel

A chapel dedicated to St Catherine of Alexandria is known to have existed on the site since 1157, when the Prior of Durham agreed to allow Romanus de Hilton to appoint his own chaplain for the chapel, subject to the prior's approval.[29] In return, de Hilton was to provide an annual contribution of 24 sheaves of oats for every draught ox he owned, to the nearby monastery at Monkwearmouth, and was required to attend the mother church of St Peters for the feasts of the Nativity, Easter, Whitsuntide and Saints Peter and Paul.[29] In 1322, there was a chantry dedicated to the Virgin Mary and there were three chantry priests in 1370.[30]

The chapel, which is on a small embankment to the north east of the castle, was rebuilt in stone in the early 15th century. It was modified from the late 15th to late 16th century, when a Perpendicular Gothic, five-light east window and transepts were added.[8] Bucks' engraving of 1728, shows a short nave and a large six-light west window, and that the chapel was disused by this time, as it had no roof.[31] The west façade of the chapel was later demolished and the chancel arch was built up to form a new one with a Gibbs surround.[31] A bell-turret was added c. 1805.[31] On the north and south sides of the chapel are two transeptal, semi-octagonal bays.[31]

Although repairs to the chapel were carried out by the last Baron Hylton and the successive owners in the 19th century, it fell into disrepair until, like the castle, it was taken over by the state in 1950.[10]

Modern

The castle and chapel have been Grade I listed buildings since 1949 and form a Scheduled Ancient Monument under the care of English Heritage, who took over the site in 1984, although Sunderland City Council own the land. In 1999, the Friends of Hylton Dene group was formed by residents of the estates around North Hylton "with the aim of co-operating with Sunderland City Council, Durham Wildlife Trust and other agencies to actively involve the local community in the development and upkeep of Hylton Dene and Castle". In December 2007, the group was awarded £50,000 by the Heritage Lottery Fund to carry out a survey for the future for the site.[32] Once restored, the castle could be opened. The chairman of the Castle in the Community John Coulthard described the castle, Sunderland's second oldest building, as "an asset in the city – it is a lovely setting and we would love to see it bring in some income".[33]

There have been four organised International Reunion(s) of Hylton Families over the past few years; most notably on 4 July 2004, when around fifty American descendants of the Hylton family visited the castle to present a flag featuring the Hylton blazon.[34] The flag now flies from the recently installed flagpole, provided by English Heritage.[34]

Exterior

The west façade of the castle has square towers flanking the central bay, with others at the south west and north west, all topped with octagonal, machicolated turrets.[8] The north and south façades are relatively simple. The east façade has a central projection in the centre rising a storey above the parapet, to form a tower.[35] The tower's south angle is splayed to accommodate the main staircase and only the corbels of its parapet survive.[35] The screen closing off the east entrance has a three-bay cusped arcade on the ground floor and three ogee arches on the shafts above.[35]

The roof was originally covered with sheet lead and adorning the roof are stone warriors and other figures, similar to those of Raby, Alnwick and the gates of York.[7][8][36] Originally there were four figures on each corner turret and bartizan; only five have survived.[36] Between the central towers once stood a sculpture of a knight in combat with a serpent (of which only fragments survive), believed to pertain to the tale of the Lambton Worm.[21][36] The parapet is also machicolated (except on the north façade) and continued between the central towers by a carved-foliage arch (originally with cusping which fell in 1882), instead of corbels.[8][11] Another feature of the roof was shallow stone troughs on the battlements which fed scalding oil or water into the machiocaltions as a means of defence.[36] In a small chamber in each turret or bastion, a brazier was kept burning to bring the liquids to a suitable temperature.[36]

Interior layout

Before the changes made by John Hylton (died 1712), the castle's layout plan was as follows:

The ground floor, accessed directly from the outside courtyard, led into a portcullis-protected, vaulted passage, eleven feet wide and extending the depth of the building. On either side of the passage were two vaulted rooms. The room nearest the entrance on the right was a guardroom or the porter's room, which housed a well; the back-right room, with a garderobe located in the south west turret (accessed via a passage running along the south wall), was for an official.[35][37] The other two rooms to the left were used to house staff or storage.[35][37]

The first was floor was accessed via the main staircase, situated in the east tower.[35] The first room encountered was the great hall, which rose three floors. To the viewer's immediate left was a kitchen (with clerestory lighting), and further on to the left was a butlery and pantry with a garderobe.[35] To the viewer's back right was a small passage containing a private staircase and the entrance to the oratory (its roof vaulted with an east window) in the east tower.[35][38] The oratory was entered via a five-and-a-half high pointed-arch doorway and contained an altar and piscina, of which only an ornamental niche remains.[35][38] There was a fireplace on the north wall of the great hall and behind the north wall was the great chamber containing a fireplace, garderobe and a window seat on the east wall.[35][37] To the west of the hall was the head of the west window.[35] The portcullis is believed to have been raised into the hall in front of this window.[35]

The kitchen, oratory and great chamber rose two floors, therefore only the minstrels' gallery was accessed via the main staircase on the second floor. However, the butlery and pantry was single-storeyed, but held the butler's chamber (with a garderobe) above it, accessed either via a staircase in that room or via the gallery.[37]

The rooms on the north and east sides of the third floor were accessed via the private staircase.[37][38] The rooms were two family rooms, one above the oratory and a larger one above the great chamber.[37][38] The larger one had a fireplace and a garderobe, and was likely the baron's bedroom; the smaller room was either the chaplain's quarters or a family room.[37][38] Both were connected via a lobby at the top of the private staircase.[37][38]

The room on the south side (separated by the other rooms due to the hall's height) was accessed via the main staircase. This room also had a fireplace and a garderobe, and was probably used by guests.[37]

Above the small family/chaplain's room on the third floor, was the servant's room with a corner fireplace and two windows on the mezzanine floor, accessed via the main staircase.[36][37] Above, on the roof level, was the Warder's Chamber containing a stone-hooded fireplace, beamed ceiling, two small windows in the east wall and a garderobe.[36][39] There were also four closet-chambers in the turrets on the roof, used by staff.[39]

Heraldry

The castle and chapel are adorned with heraldic devices and shields of arms, providing information as to when the castle was constructed.

West façade

Above the main entrance on the western façade of the castle, there are twenty shields of arms. They are believed to show the political alliances of the early Hyltons, as the banner of the king, and the arms of nobles and knights of Northumberland and the County Palatine of Durham are shown.[27] In relation to the photograph, the shields are:[40]

(click image for numbering)

- England and France quarterly – The banner of Henry IV of England

- Quarterly 1 and 4: Or a Lion rampant Azure (Percy); 2 and 3: Gules, three luces haurient Argent (Lucy) – Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland

- Percy (unquartered) – Sir Henry "Hotspur" Percy (son of the above)

- A Lion rampant debruised by a bend – Sir Peter Tilliol

- Within a bordure two Lions passant – Felton of Edlington

- Azure, three herons Argent – Sir William Heron

- A Lion rampant – believed to be the Royal coat of arms of Scotland

- Quarterly, Argent, two bars Azure and Or six annulets Gules (Hylton quartering Hylton of Swine) – The Westmoreland branch of the Hyltons.

- Argent, a fess Gules inter three popinjays Vert – Sir Ralph Lumley (later Baron Lumley)

- A Lion within a bordure engrailed – Sir Thomas Grey (or his son)

- Or and Gules quarterly, over all on a bend three scallops – Sir Ralph Evers (Eure)

- Azure, a chief dancette Or – FitzRanulph of Middleham

- Argent, two bars, and three mullets in chief – Sir William Washington

- Argent, a fess inter three crescents Gules – Sir Robert Ogle

- William de Ros, 6th Baron de Ros

- Ermine, on a canton Gules an orle Or – Sir Thomas Surtees

- Ermine, three bows Gules – Sir Robert Bowes (ancestor of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon)

- Thomas Weston, chancellor to Bishop Skirlaw

- Walter Skirlaw (Bishop of Durham 1388–1406)

- Argent, two bars Azure – Sir William Hylton

Although it was necessary for Briggs to move the Hylton banner to make way for a new entrance, it can be seen from a colour version of Bucks' engraving that the shields were previously placed not as they are today (particularly Weston and Skirlaw's).[41] Briggs is believed to have re-arranged the shields, disrupting their original hierarchical arrangement.[27] Nevertheless, the arms give a date for the construction and completion of the castle as between 1390 and the early 15th century, due to the following reasons:

- The Earl of Northumberland quartered his own arms with those of his second wife, Maud Lucy, after their marriage in c.1384.[27]

- Sir Henry "Hotspur" Percy did not quarter his own arms with those of Lucy, until he inherited the Honour of Cockermouth from his stepmother in 1398.[42]

- The arms shown of Henry IV are those he adopted c. 1400, after simplifying the French quarters (see Armorial of Plantagenet)

East façade

The east façade of the castle features a slanted shield containing the Hylton arms (Argent, two bars Azure) and a white hart (male deer), lodged, chained and collared with a coronet, Or. The hart is possibly the badge used by Richard II of England (indicating construction began before Richard's deposition in 1399) or an earlier crest used by the family after it was granted by William I of England, in reward for the services of the previously mentioned Lancelot de Hilton.[3][12] A "Moses head" (the crest of the Hylton arms) also features on the east façade.[12][43]

Hauntings

There is a local tradition that Hylton Castle is haunted by the spirit of Robert Skelton, known as the Cauld (a pronunciation of "cold" in Mackem) Lad of Hylton. Various versions of how he was killed exist, the most popular being that he was decapitated by Sir Robert Hylton (later de jure 13th Baron Hylton), after falling asleep and failing to get his master's horse ready on time.[44] Skelton's spirit then began to haunt the castle and would move objects, either misplacing them or tidying up.[45] The spirit was said to have been finally laid to rest when the castle servants put a cloak out for him.[46]

References

- Whittaker, p.83

- Fry, p.246

- "History". Friends of Hylton Dene. Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- "Sunderland wins £5.4million to bring Old Fire Station and Hylton Castle back to life". www.sunderlandecho.com.

- Sykes, p.9

- Timbs & Gunn, p.283

- Billings, p.47

- Pevsner, p.471

- Pevsner, p.470

- "Hylton Castle & Dene" (PDF). Sunderland Public Libraries Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- Pettifer, p.30

- The Gentlemen's Magazine — Review – Surtees's History of Durham, March 1821, p.234.

- Meadows & Waterson, p.42

- "Listed Buildings – Number:920-1/3/281". Sunderland City Council. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- "Doorway of the Golden Lion, South Hylton". England's Past for Everyone. Archived from the original on 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- Sykes, p.220

- "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to 2007". Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- "Mary Eleanor Bowes". Sunniside Local History Society. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- Meadows & Waterson, p.43

- 1841 England Census: Class: HO107; Piece 299; Book: 2; Civil Parish: Monkwearmouth; County: Durham; Enumeration District: 12; Folio: 17; Page: 2; Line: 1; GSU roll: 241347.

- Billings, p.48

- "Hylton Castle Estate Sale 1862" (PDF). England's Past for Everyone. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- Meadows & Waterson, p.44

- Hugill, p.62

- "Castle Owner's Church Faces Demolition". redOrbit. 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- "Hylton Colliery". Durham Mining Museum. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- Emery, p.107

- "Hylton Castle, investigation history". Pastscape.org.uk. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- Huggill, p.58

- "Scheduled Monuments. Hylton Castle: a medieval fortified house, chapel, 17th and 18th century". Sunderland City Council. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- Pevsner, p.473

- "Hylton Castle's future – you decide". Sunderland Echo. 2008-04-21. Archived from the original on 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- "Derelict castle could be reopened". BBC Online. 2008-03-18. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- "Hylton Castle". Local Heritage Initiative. Archived from the original on 2008-03-31. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- Pevsner, p.472

- Huggill, p.60

- Emery, p.108

- Huggill, p.59

- Emery, p.109

- "Heraldry". Friends of Hylton Dene. Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- "West View of Hylton Castle, in the Bishoprick of Durham". Panteek. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- "The Secrets of Hylton Castle". AncestryUK.com. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- "The Davis-Bean Trees". Kerry S. Davis. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- Sarah Stoner (November 28, 2007). "Was the Cauld Lad murdered after all?". Sunderland Echo. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Ghosthunter (September 15, 2004). "The chilling story of our most famous phantom (and one less well known)". Sunderland Echo. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Joseph Jacobs (April 15, 2005). "The Cauld Lad of Hylton". Surlalune Fairytales. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

Bibliography

- Billings, Robert William (1844). Architectural Antiquities of the County of Durham.

- Emery, Anthony (1996). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500. vol.11. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-49723-X.

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset (1980). Castles of the British Isles. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7976-3.

- Hugill, Robert (1979). The castles & towers of the county of Durham : a guide to the strongholds of the ancient Palatinate of Durham. Newcastle: Frank Graham. ISBN 978-0-85983-106-2.

- Pettifer, Adrian (1995). English Castles, A guide by counties. Woodbridge. ISBN 0-85115-782-3.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (1983). The Buildings of England: Durham. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-300-09599-6.

- Sykes, John (1866). Local Records of Northumberland and Durham. vol. 1.

- Timbs, John; Gunn, Alexander (1872). Abbeys, Castles and Ancient Halls of England and Wales. vol.3. London.

- Waterson, Edward; Meadows, Peter (1993). Lost Houses of County Durham. ISBN 0-9516494-1-8.

- Whittaker, Neville (1975). Old Halls and Manor Houses of Durham. Frank Graham. ISBN 0-85983-047-0.

Further reading

- Billings, Robert William (1846), Illustrations of the County of Durham: ecclesiastical, castellated, and domestic, pp. 42–44

- Boyle, John Roberts (1892), Comprehensive Guide to the County of Durham: its Castles, Churches, and Manor-Houses, pp. 546–52

- Brayley, Edward Wedlake; Britton, John (1803), Beauties of England and Wales, 5, pp. 150–2

- Corfe, Tom, ed. (1992), "The Visible Middle Ages", An Historical Atlas of County Durham, pp. 28–9, ISBN 0-902958-14-3

- Harvey, Alfred, Castles and Walled Towns of England (Methuen and Co), 1911

- Hutchinson, William (1785–94), The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham, 2, pp. 638–40

- Hutton, Matthew P. (1999), Hylton Castle Ghost, Island Light Publishing

- Jackson, Michael, Castles of Northumbria: Gazetteer of the Medieval Castles of Northumberland and Tyne and Wear (Medieval Castles of England) (Carlise), 1992, pp. 143–4 ISBN 0-9519708-0-1

- King, David James Cathcart (1983), Castellarium Anglicanum: An Index and Bibliography of the Castles in England, Wales, and the Islands, 1, Kraus, p. 136, ISBN 0-527-50110-7

- Mackenzie, Bt., Sir James Dixon, Castles of England (Heinemann), 1897, volume 12, pp. 343–6

- Salter, Mike (2002), The Castles and Tower Houses of County Durham, ISBN 1-871731-56-9

- The Time Team Reports (Series 2), 1995, pp. 29–33

- Surtees, Robert (1972) [1816–40], History and Antiquities of Durham, pp. 20–4 and plate, ISBN 0-85409-814-3

- Turner, Thomas Hudson; Parker, John Henry (1859), Some account of Domestic Architecture in England, 13, p. 206

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hylton Castle. |

- Hylton Castle information at English Heritage

- The Friends of Hylton Dene

- BBC Wear – Inside Hylton Castle pictures

- Time Team – Episode exploring the Castle