Ingleton, North Yorkshire

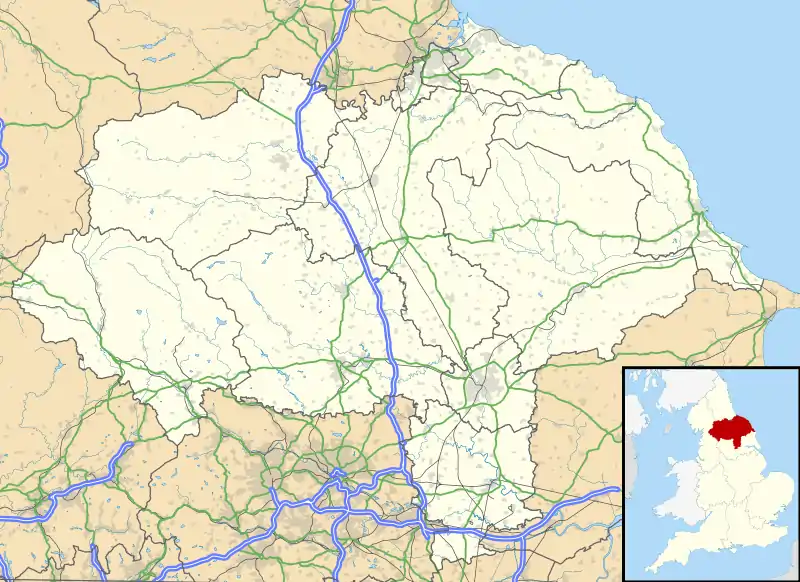

Ingleton is a village and civil parish in the Craven district of North Yorkshire, England. The village is 19 miles (30 km) from Kendal and 17 miles (28 km) from Lancaster on the western side of the Pennines. It is 9.3 miles (15 km) from Settle. The River Doe and the River Twiss meet to form the source of the River Greta, a tributary of the River Lune. The village is on the A65 road and at the head of the A687. The B6255 takes the south bank of the River Doe to Ribblehead and Hawes. All that remains of the railway in the village is the landmark Ingleton Viaduct.[2] Arthur Conan Doyle was a regular visitor to the area and was married locally, as his mother lived at Masongill from 1882 to 1917 (see notable people). There is growing evidence to support a claim that the inspiration for the name Sherlock Holmes came from here.[3]

| Ingleton | |

|---|---|

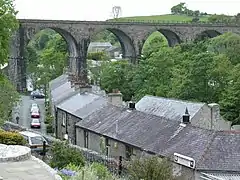

Ingleton and the viaduct across Swilla Glen | |

Ingleton Location within North Yorkshire | |

| Population | 2,186 (2011 census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SD691729 |

| • London | 205 mi (330 km) SE |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CARNFORTH |

| Postcode district | LA6 |

| Dialling code | 015242 |

| Police | North Yorkshire |

| Fire | North Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| UK Parliament | |

Whernside, 5.7 miles (9.2 km) NNE of the village, one of the Yorkshire Three Peaks, is the highest point in the parish at 736 metres (2,415 ft).

There are major quarries within the parish. Ingleton Quarry is active Meal Bank Quarry no longer is, but extracted Carboniferous limestone and possesses an early Hoffman kiln. There was a textile mill, and the coalfield supported twelve or more small collieries, but Ingleton is mostly known for its tourism, being partially in the Yorkshire Dales National Park, offering waterfalls in a SSSI, limestone caves and Karst landscape walking opportunities.

History

Ingleton and the surrounding area was settled in the Iron Age by the Brigantes who built a hill fort on top of Ingleborough with walls a 0.62-mile (1 km) in circumference. It is thought that the Romans defeated the Brigantes in battle and built a fort alongside the hill fort.[4] The valley was crossed by Roman roads as Ingleton was a strategic river crossing. By the 12th century the Normans had built a church in the village.[5]

Manor

Willian Lowther (1574–1641) of Ingleton Hall was Lord of the Manor, Justice of the Peace for the West Riding and had seven children. His son Richard (1602–1645) inherited the manor and two sons joined the church. His daughter Frances (1612–1665) married John Walker who leased the Ingleton Colleries, and Elizabeth (1615–?) married Anthony Bouch in 1633[6] and mortgaged Ingleton Manor.[7]

Richard Lowther (Collonell(sic), governor of Pontefract) and his son Gerrard were on the losing Royalist side at the Civil War siege of Pontefract Castle in 1645, and later at Newark. The war ended and his father dead, Gerrard was fined by the new government for his delinquency, and entered into a series of agreements to pay the debt and court appearances to maintain the estate. The Lord of Manor title had passed to Anthony Bouch by 1665, and the coal rights passed to the Walker family after a settlement in the chancery court in 1678.[7]

Industry

The Ingleton Coalfield was worked for 400 years. It is about 6 miles long by 4-mile wide and extends into the neighbouring parishes of Burton in Lonsdale and Thornton-in-Lonsdale. The coalfield terminates at the South Craven fault. The coal measures are shallow and represent the lowest layers in the Pennine coal measures sequence. The earliest coal mining occurred along the River Greta where Four Foot and Six Foot seams outcrop. Most deep mining was at New Ingleton Pit sunk in 1913. Its sinking led to the discovery of the Ten Foot seam (house and steam coal) at 127 yards, and the Nine Foot seam (steam and house coal) at 134 yards. Beneath them are the Four Foot seam (house, gas and coking coal) at 233 yards, the Three Foot seam (house and gas coal) at 236 yards and the Six Foot seam (steam and house coal) at 260 yards. Commercially viable deposits of fireclay lay under the Three Foot seam and pottery clay beneath the Six Foot seam used to make Ingleton Bricks.[8][9] The Walkers achieved their legal victory through a son-in-Law William Knipe. Thomas Moore (?–1733) was the second husband of Marianne Walker and between 1702 and 1711 bought out other share holders in the collieries while building a successful medical practice in Wakefield. He left the collieries to be managed by an agent. His daughter Susannah married William Serjeantson- and his family ran the collieries from 1736 to 1828. Coal was delivered by horse and cart.[10] Ingleton and Bentham Moors were enclosed in 1767. Plans were drawn up in 1780 to connect Ingleton to the Leeds & Liverpool Canal via Clapham, Settle and Foulridge, Colne but it never progressed.[11] Boys and girls as young as four worked the collieries in the 1780, first as 'messengers' and from six, underground, as 'trailers', pulling coal tubs.[12] The last mine was closed in 1940.[13]

Ingleton Mill was built in 1791 by four partners who also had built a mill in Clapham in 1786. The partners, George Armitstead, a cotton spinner, Ephraim Ellis, William Petty and Thomas Wigglesworth bought the barn beside the old corn mill and built the mill. They obtained iron for its construction from Kirkstall Forge. They ran a joiner's shop, smithy and cotton mill. It was sold in 1807 and used to spin flax by John Coates, before reverting to cotton spinning in 1837.[14] (National Building Register:63815: [15]).

Governance

Ingleton is a civil parish. The parish council has 11 councillors and elections are held every four years.[16] The village is a part of the Ingleton & Clapham ward of Craven District Council and returns two members.[17] This ward had a population taken at the 2011 census of 3,808.[1] The village is within the Skipton and Ripon parliamentary constituency, represented by Julian Smith, a member of the Conservative Party, as of the 2010 general election.[18]

Geography

The civil parish of Ingleton is extensive, stretching from Blea Moor near Wold Fell SD 793847 in the north to Newby Moor SD 704698 in the south. The north of the parish follows the county boundary with Lancashire to Whernside SD 739816. From here it follows the ridge south-west to West Fell and down to Thornton Force on the River Twiss, and thence along the river, and the River Greta to Fourlands Hill SD 698713. The east of the parish follows the watershed of the River Ure, a headwater of the River Humber, and the River Ribble to Grove Head where it is only 200m from the Pennine Way, it drops to the B6255 road and the River Ribble at the milepost at SD 793816. The boundary follows the Ribble through Ribblehead, then takes the ridge through Park Fell and Simon Fell to Ingleborough. It passes due south over Ingleborough Common to Newbury Moss, descending to Cold Cotes on the old road at SD 722712. Ingleborough is 2,373 feet (723 m) high.[19]

The village sits at the foot of Ingleborough, separated from Thornton-in-Lonsdale by the Rivers Greta and Twiss, some of the facilities that form the settlement being thus outside the civil parish. The peaks of Ingleborough and Whernside lies within the parish; separated by the deeply eroded valley of the River Doe. Both these peaks are formed by millstone grit on limestone footings. To the north of the river are the Twistleton Crags with the important limestone pavement of Scales Moor. Here are two SSSIs: Whernside and Scales Moor Common which is managed as stinted common pasture land.[lower-alpha 1] To the south of the river is one SSSI: Ingleton on the stinted Ingleton Common, in the number of an equivalent limestone pavement. This area of challenging potholes and caves.[20] The show cave White Scar Caves SD 712745 has its entrance. Ingleton Common adjoins Clapham Common and they are collectively referred to as Ingleborough Common.

Historically, mining and agriculture were the predominant industries in the area. Coal was extracted from the Ingleton Coalfield from the early 1600s, to the turn of the 20th century, eventually closing in 1936. The New Village estate was built for mine workers.[21]

Geology

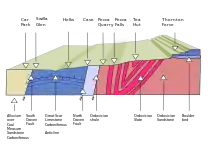

A varied geology is found within the boundaries of the parish, ranging from rocks laid down in the Iapetus Ocean in Ordovician times, through the Carboniferous limestones of the Askrigg Block on Whernside and Ingleborough and coal measures within the Craven Basin, to the Quaternary drumlin field in Ribblehead. It is a classic field study area for students of geology.[23]

Much of the parish is dominated by Carboniferous deposits deposited on the submarine platform of the Askrigg Block, which was a relatively high area forming a shelf sea buoyed up by Devonian Wensleydale Granite.[24] It is separated from the Craven Basin to the south and west by the Craven Fault system.[25] The lower Carboniferous deposits are dominated by the 200 metres (660 ft) thick Great Scar limestones laid down during the Viséan stage. A mature karst landscape has formed where it outcrops, with bare limestone pavements, subterranean streams, and major solutional cave systems such as White Scar Caves and Meregill Hole.[26] Scales Moor on the Whernside flanks of Chapel-le-Dale has one of the largest exposures of pavement in the Dales, measuring some 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) long 800 metres (870 yd) wide.[27] On Whernside and Ingleborough above the flat plateau formed by the top of the Great Scar limestone, are the Brigantian and Namurian aged Yoredale cyclothem sequences of sandstone, limestone, and shales which were deposited on the edge of a huge delta.[28] The upper ramparts of these hills are capped by thick beds of Grassington Grit, a course poorly-sorted sandstone laid down in shallower water as the delta prograded south.[29]

The Carboniferous rocks were deposited unconformably onto basement rocks which are exposed as inliers in Chapel-le-Dale and lower Kingsdale (Swilla Glen). They are Ordovician in age, deposited as turbidites about 480 million years ago in the Iapetus Ocean, and heavily folded and lightly metamorphosed in late Ordovician times. They are currently quarried for roadstone, and were once quarried for slate in the Ingleton Glens.[30]

Just to the north of Ingleton village the Craven Faults running north-west to south-east mark the southern margin of the Askrigg Block. The North Craven Fault has a downthrow of about 200 metres (660 ft), and a few hundred yards away the South Craven Fault has a downthrow of about 1,200 metres (3,900 ft).[25] The fault plane of the North Craven Fault is exposed in Swilla Glen.[31] To the south of the Craven Faults is the Craven Basin where the Westphalian stage Pennine Coal Measures are exposed, once exploited by the Ingleton coalfield.[32]

The landscape in the north-east of the parish, beyond the Ribblehead Viaduct, is dominated by Devensian glacial deposits, and includes some of the Ribblehead Drumlin Field.[33]

Economy

Tourism, mostly from hiking and caving, accounts for most of the economic activity of the village, especially in spring and summer. There are craft businesses, such as pottery.[34]

Of two quarries in the parish, Ingleton Quarry, owned by Hanson Aggregates,[35] is active and extracts Ordivician greywacke for roadstone[36] but Meal Bank Quarry that extracted Carboniferous limestone and possessed an early Hoffman kiln is no longer active.[37]

In 1933 an open-air swimming pool was constructed by volunteers, with materials supplied by the New Ingleton Colliery.[38] The European (Objective 5b) Community Fund, the National Lottery and private donations have been used to improve and modernise the pool.[39]

Landmarks

This area of Craven is best known for its natural landmarks, since the parish includes the summits of two of the Yorkshire Three Peaks, Ingleborough and Whernside. Two miles north east of the village on the road to Chapel-le-Dale are the show caves at White Scar Caves.[40] An access tunnel has been cut to allow visitors to visit.

The Ingleton Waterfalls Trail is a five-mile (8 km) circular walk from the village, opened in 1885.[41]

Ingleton Viaduct is a Grade II listed structure in the village.[42] Six miles to the north east on Batty Moss is the Ribblehead Viaduct, a Grade II* listed structure on the Settle and Carlisle Line, and on the land underneath and around it, the scheduled remains of the construction camp and navvy settlements.[43]

Religion

The parish church is dedicated to St Mary There is also a Methodist chapel and an Evangelical Church.[44] The parish church, designed by Cornelius Sherlock dates principally from 1886 and is dedicated to St Mary the Virgin. It is built on the site of an earlier church. It stands on a bank of boulders and sediment from the last ice age which make for unstable foundations. The Norman font is dated at around 1150, and the 15th-century tower is built in the perpendicular style. The nave was replaced on new compacted foundations in 1743 but demolished in 1886 to make way for the present one, which is built in blue limestone from Skirwith Quarry. The foundations were consolidated with concrete in 1930 and again in 1946. The church was dedicated to St Leonard but in the 18th century the dedication was changed.[45] Other treasures include a Vinegar Bible and a reredos with a carving of the Last Supper.

Transport

Ingleton had two railway stations at opposite ends of Ingleton Viaduct. Ingleton (Midland) station opened for ten months only in 1849, then reopened in 1861 until 1954. Ingleton (L&NW) station opened along with the Ingleton Branch Line in 1861, but such was the rivalry between competing railway companies that initially passengers were forced to walk between the stations across the Greta valley floor, despite the viaduct between them. The L&NW station closed in 1917.[46][47] The nearest railway station is now Bentham, 3.5 miles (6 km) by road to the south of Ingleton.

The village is on the A65 road between Skipton and Kendal and at the head of the A687 that branches westwards towards Burton in Lonsdale and Lancaster. The B6255 takes the south bank of the River Doe heading northeast to Chapel-le-Dale, Ribblehead and Hawes.

Population change

| Population changes in Ingleton, North Yorkshire since 1801 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | |||||

| Population | 1106 | 1268 | 1302 | 1228 | 1355 | 1391 | --- | 2541 | 1625 | 1568 | 1672 | 1672 | 2464 | 2227 | ---[lower-alpha 2] | 1887 | --- | |||||

| Sources: Vision of Britain,[49] Online Historical Population Reports,[50] and 2001 and 2011 UK Census Data | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Education

There is now one school in the village, Ingleton Primary School.[51] It is a partner in 'The Three Peaks Family of Schools', a grouping of secondary schools, primary schools and middle schools.[52] serving North Craven. Ingleton Primary School is a small school, that teaches pupils in mixed classes, two classes serve the Key stage 1 pupils, years 3 and 4 are together and years 5 and 6.[51]

This was once a first school until the re-organisation on 31 August 2012. The pupils transferred to the adjacent Ingleton Middle School after year 5, at the age of ten. They remained here until 13 when the transferred to the upper school in Settle. The Middle School buildings are now used as a Community Information Centre which is run as a not-for-profit organisation.[53] The playing fields have been sold.[54] Settle Middle school buildings were transferred to Settle College to provide the extra capacity needed for two extra year groups.[55]

Students from Ingleton transfer at the age of eleven to the receiving secondary schools, Settle College[56] and Queen Elizabeth School, Kirkby Lonsdale.[57] After secondary education pupils can either stay on to sixth form or transfer to a local college like Kendal College, Lancaster and Morecambe College.

Facilities

Ingleton has a community open air swimming pool which is closed in the winter.

Notable people

Reverend Thomas Dod Sherlock was vicar of St Mary the Virgin, Ingleton from 1874 to 1879, while his Uncle Edgar was Rector of Bentham. His father, Randall Hopley Sherlock, a Liverpool newspaper proprietor, was killed by lightning at Ingleton (Midland) railway station on 9 August 1875 while visiting his son. A stained glass window is dedicated to his memory in the church tower.

The area below the north end of Ingleton viaduct is known as Holme Head.

Mary Doyle, the mother of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, lived from 1882 to 1917 in Masongill, a hamlet near Thornton-in-Lonsdale. In 1885 Arthur, a regular visitor to the area, was married to his first wife Louise in St Oswald's Church, Thornton-in-Lonsdale.[58][59] When visiting his mother, Arthur would have arrived at Ingleton (Midland) railway station, where Randall Sherlock died, and continued his onward journey by cart to Masongill passing through Holme Head.

In 1886 when Conan Doyle wrote A Study in Scarlet, the first Sherlock Holmes story, he was originally going to call his hero Sherrinford Holmes. That same year, St Mary the Virgin, Ingleton, was rebuilt to the design of Cornelius Sherlock, the celebrated Liverpool architect responsible for the Picton Reading Room and the Walker Art Gallery, both now listed buildings in Liverpool. Pupils of Storrs Hall School, Ingleton, raised the funds to purchase a brass lectern for the new church. Pupils of this private school for young ladies at that time included Conan Doyle's two youngest sisters.

References

Footnotes

- Stinted common land is a system where the commoners are restricted to the sheep they can keep in the common; this prevents overgrazing

- No census was taken in 1941, due to the Second World War.[48]

Notes

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Ingleton Parish (1170216762)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- OS map 98, Wensleydale and Upper Wharfdale.

- Tunningley, Alan (11 July 2015). "Dales link to Sherlock Holmes' creation". The Westmorland Gazette. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Richmond, I. A. (24 September 2012). "Queen Cartimandua". Journal of Roman Studies. 44 (1–2): 43–52. doi:10.2307/297554.

- "St Mary the Virgin Ingleton". A Church Near You. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, p. 19.

- Ellis (1993). "The Ingleton Coalfield—A Slumbering Dwarf?". Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, p. 45.

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, p. 25.

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, p. 29.

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, p. 27.

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, pp. 95-121.

- Ingle 1997, p. 204.

- "NBR63815". Yorkshire Industrial Heritage.

- "Parish Council". Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- "District Council". Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- "Parliament". Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- Mapit overlay

- -Modern Environmental Governance: Qualitative Research Data Case Study : Ingleton North Yorkshire (PDF) (Report).

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, p. 115.

- CPGS 2003, p. 8.

- "Ingleton Virtual Field Excursion". Liverpool John Moores University. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Waltham 2007, p. 18.

- Waltham 2007, pp. 54–57.

- Waltham et alia 1997, pp. 46–55.

- Waltham et alia 1997, pp. 43–46.

- Waltham 2007, pp. 30–31.

- Waltham 2007, pp. 40–45.

- Waltham 2007, pp. 14–18.

- Waltham 2007, p. 91.

- Waltham 2007, pp. 50.

- Waltham 2007, pp. 76–77.

- "Economy". Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- Kidd, Adrian. "The 'Your Dales Rocks Project' – A Draft Local Geodiversity Action Plan (2006–2011) for the Yorkshire Dales and the Craven Lowlands". North Yorkshire Geodiversity Partnership. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Waltham 2007, p. 15.

- CPGS 2003, p. 14.

- Bentley, Bond & Gill 2005, p. 118.

- "Ingleton Swimming Pool".

- White Scar Cave- Caving notes

- Ingleton Waterfalls Trail. "History of the Trail". Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- Historic England. "Ingleton Viaduct (1335083)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Historic England. "Ribblehead railway construction camp and prehistoric field system (Grade II*, scheduled) (1015726)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Churches". Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- St Marys church, Ingleton: about the church Archived 16 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Western, Robert (1990), The Ingleton Branch, Oakwood Press, Oxford, ISBN 0-85361-394-X, p.29

- "The National Archives - Homepage". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Ingleton CP: total population". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- "Census". Online Historical Population Reports. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- "Ingleton Primary School". Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "The Three Peaks Family of Schools". Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- "NYCC Executive Papers" (PDF). 18 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2014.

- "School Playing Fields in North Yorkshire Sold Off". Minster FM. 17 August 2012. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Proctor, Katie (22 February 2011). "Ingleton and Settle middle schools closure confirmed".

- "Settle College". Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- "Queen Elizabeth School". Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- St Mary's Church, Ingleton Archived 16 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.ingleton.co.uk/inghist.asp

Bibliography

- CPGS (2003). "Ingleton Waterfalls trail" (PDF). Craven and Pendle Geological Society. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- Bentley, John; Bond, Bernard; Gill, Mike (2005). "Ingleton Coalfield". British Mining. Sheffield: Northern Mine Research Society (78). ISBN 978-0-901450-58-6. ISSN 0308-2199. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- Ingle, George (1997). Yorkshire Cotton: The Yorkshire Cotton Industry 1780–1835. Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 1-85936-028-9.

- Waltham, Tony (2007). The Yorkshire Dales Landscape and Geology. Marlborough: Crowood Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86126-972-0.

- Waltham, A.C.; Simms, M.J.; Farrant, A.R.; Goldie, H.S. (1997). Karst and Caves of Great Britain. London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 0-412-78860-8.

External links

Media related to Ingleton, North Yorkshire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ingleton, North Yorkshire at Wikimedia Commons- Ingleton Viaduct, the story of an 800 foot monument to railway company irrationality

- The Original Ingleton Village website

- Ingleborough Webcam Site

- LJMU Virtual Field Trip- The Geology Site

- Ingleborough Archaeology Group Reports from excavations.