Isaac Israeli ben Solomon

Isaac Israeli ben Solomon (Hebrew: יצחק בן שלמה הישראלי, Yitzhak ben Shlomo ha-Yisraeli; Arabic: أبو يعقوب إسحاق بن سليمان الإسرائيلي, Abu Ya'qub Ishaq ibn Suleiman al-Isra'ili) (c. 832 – c. 932), also known as Isaac Israeli the Elder and Isaac Judaeus, was one of the foremost Jewish physicians and philosophers living in the Arab world of his time. He is regarded as the father of medieval Jewish Neoplatonism. His works, all written in Arabic and subsequently translated into Hebrew, Latin and Spanish, entered the medical curriculum of the early thirteenth-century universities in Medieval Europe and remained popular throughout the Middle Ages.[2]

Isaac Israeli ben Solomon | |

|---|---|

Yitzhak ben Shlomo ha-Yisraeli | |

De febribus | |

| Died | c. 932 |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Jewish philosophy |

| School | Neoplatonism Correspondence theory of truth[1] (according to Aquinas) |

Life

Little is known of Israeli's background and career. Much that is known comes from the biographical accounts found in The Generations of the Physicians, a work written by the Andalusian author Ibn Juljul in the 2nd half of the tenth century, and in The Generations of the Nations by Sa'id of Toledo, who wrote in the mid-eleventh century.[3] In the thirteenth century, Ibn Abi Usaybi'a also produced an account, which he based on Ibn Juljul as well as other sources, including the History of the Fatimid Dynasty by Israel's pupil Ibn al-Jazzar.[4]

Israeli was born in around 832 into a Jewish family in Egypt. He lived the first half of his life in Cairo where he gained a reputation as a skillful oculist. He corresponded with Saadya ben Joseph al-Fayyumi (882-942), one of the most influential figures in the medieval Judaism, prior to his departure from Egypt. In about 904 Israeli was nominated court physician to the last Aghlabid prince, Ziyadat Allah III. Between the years 905-907 he travelled to Kairouan where he studied general medicine under Ishak ibn Amran al-Baghdadi, with whom he is sometimes confounded ("Sefer ha-Yashar," p. 10a). Later he served as a doctor to the founder of the Fatimid Dynasty of North Africa, 'Ubaid Allah al-Mahdi, who reigned from 910-934. The caliph enjoyed the company of his Jewish physician on account of the latter's wit and of the repartees in which he succeeded in confounding the Greek al-Hubaish when pitted against him. In Kairouan his fame became widely extended, the works which he wrote in Arabic being considered by the Muslim physicians as "more valuable than gems." His lectures attracted a large number of pupils, of whom the two most prominent were Abu Ja'far ibn al-Jazzar, a Muslim, and Dunash ibn Tamim. Israeli studied natural history, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and other scientific topics; he was reputed to be one who knew all the "seven sciences".

Biographers state that he never married or fathered children. He died at Kairouan, Tunisia, in 932. This date is given by most Arabic authorities who give his date of birth as 832. But Abraham ben Hasdai, quoting the biographer Sanah ibn Sa'id al-Kurtubi ("Orient, Lit." iv., col. 230), says that Isaac Israeli died in 942. Heinrich Grätz (Geschichte v. 236), while stating that Isaac Israeli lived more than one hundred years, gives the dates 845-940; and Steinschneider ("Hebr. Uebers." pp. 388, 755) places his death in 950. He died in Kairouan.

Influence

In 956 his pupil Dunash Ibn Tamim wrote an extensive commentary on Sefer Yetzirah, a mystical work of cosmogony which attributes great importance to the letters of the Hebrew alphabet and their combinations in determining the structure of the universe. In this work he cites Israeli so extensively that a few nineteenth-century scholars misidentified the commentary as Israeli's.

Israeli's medical treatises were studied for several centuries both in the original Arabic and in Latin translation. In the eleventh century, Constantine Africanus, a professor at the prestigious Salerno school of medicine, translated some of Israeli's works into Latin. Many medieval Arabic biographical chronicles of physicians list him and his works.

Israeli's philosophical works exercised a considerable influence on Christian and Jewish thinkers, and a lesser degree of influence among Muslim intellectuals. In the twelfth century, a group of scholars in Toledo transmitted many Arabic works of science and philosophy into Latin. One of the translators, Gerard of Cremona, rendered Israeli's Book of Definitions (Liber de Definicionibus/Definitionibus) and Book on the Elements (Liber Elementorum) into Latin. Israeli's work was quoted and paraphrased by a number of Christian thinkers including Gundissalinus, Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Vincent de Beauvais, Bonaventura, Roger Bacon and Nicholas of Cusa. Isaac Israeli's philosophical influence on Muslim authors is slight at best. The only known quotation of Israeli's philosophy in a Muslim work occurs in Ghayat al-Hakim, a book on magic, produced in eleventh-century Spain, translated into Latin and widely circulated in the West under the title Picatrix. Although there are passages which correspond directly to Israeli's writings, the author does not cite him by name.

His influence also extended to Moses Ibn Ezra (c. 1060-1139) who quotes Isaac Israeli without attribution in his treatise The Book of the Garden, explaining the meaning of Metaphor and Literal Expression. The poet and philosopher Joseph Ibn Tzaddiq of Cordoba (d. 1149) authored a work The Microcosm containing many ideas indebted to Israeli.

As Neoplatonist philosophy waned, in addition to the Galenic medical tradition of which Israeli was a part, the appreciable influence of Isaac Israeli diminished as well.

Claimed works

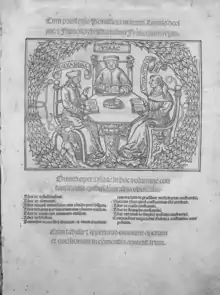

A number of works in Arabic, some of which were translated into Hebrew, Latin and Spanish were ascribed to Israeli, and several medical works were allegedly composed by him at the request of al-Mahdi. In 1515 Opera Omnia Isaci was published in Lyon, France, and the editor of this work claimed that the works originally written in Arabic and translated into Latin in 1087 by Constantine of Carthage, who assumed their authorship, were a 'plagiarism' and published them under Israeli's name, together in a collection with works of other physicians that were also and erroneously attributed to Israeli. Those works translated by Constantine of Carthage were used as textbooks at the University of Salerno, the earliest university in Western Europe, where Constantine was a professor of medicine, and remained in use as textbooks throughout Europe until the seventeenth century.

He was the first physician to write about tracheotomy in Arabic. He advised a hook to grasp the skin in the neck as Paulus of Aegina did and afterwards Avicenna and Albucasis.[5]

Medical works

- Kitab al-Ḥummayat, The Book of Fevers, in Hebrew Sefer ha-Ḳadaḥot, ספר הקדחות, a complete treatise, in five books, on the kinds of fever, according to the ancient physicians, especially Hippocrates.

- Kitab al-Adwiyah al-Mufradah wa'l-Aghdhiyah, a work in four sections on remedies and aliments. The first section, consisting of twenty chapters, was translated into Latin by Constantine under the title Diætæ Universales, and into Hebrew by an anonymous translator under the title Ṭib'e ha-Mezonot. The other three parts of the work are entitled in the Latin translation Diætæ Particulares; and it seems that a Hebrew translation, entitled Sefer ha-Mis'adim or Sefer ha-Ma'akalim, was made from the Latin.

- Kitab al-Baul, or in Hebrew Sefer ha-Shetan, a treatise on urine, of which the author himself made an abridgement.

- Kitab al-Istiḳat, in Hebrew Sefer ha-Yesodot and Latin as De Elementis, a medical and philosophical work on the elements, which the author treats according to the ideas of Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen. The Hebrew translation was made by Abraham ben Hasdai at the request of the grammarian David Kimhi.

- Manhig ha-Rofe'im, or Musar ha-Rofe'im, a treatise, in fifty paragraphs, for physicians, translated into Hebrew (the Arabic original is not extant), and into German by David Kaufmann under the title Propädeutik für Aerzte (Berliner's "Magazin," xi. 97-112).

- Kitab fi al-Tiryaḳ, a work on antidotes. Some writers attribute to Isaac Israeli two other works which figure among Constantine's translations, namely, the Liber Pantegni and the Viaticum, of which there are three Hebrew translations. But the former belongs to Mohammed al-Razi and the latter to 'Ali ibn 'Abbas or, according to other authorities, to Israeli's pupil Abu Jaf'ar ibn al-Jazzar.

Philosophical works

- Kitab al-Ḥudud wal-Rusum, translated into Hebrew by Nissim b. Solomon (fourteenth century) under the title Sefer ha-Gebulim weha-Reshumim, a philosophical work of which a Latin translation is quoted in the beginning of the Opera Omnia. This work and the Kitab al-Istiḳat were severely, criticized by Maimonides in a letter to Samuel ibn Tibbon (Iggerot ha-Rambam, p. 28, Leipsic, 1859), in which he declared that they had no value, inasmuch as Isaac Israeli ben Solomon was nothing more than a physician.

- Kitab Bustan al-Ḥikimah, on metaphysics.

- Kitab al-Ḥikmah, a treatise on philosophy.

- Kitab al-Madkhal fi al-Mantiḳ, on logic. The last three works are mentioned by Ibn Abi Uṣaibi'a, but no Hebrew translations of them are known.

- Sefer ha-Ruaḥ weha-Nefesh, a philosophical treatise, in a Hebrew translation, on the difference between the spirit and the soul, published by Steinschneider in Ha-Karmel (1871, pp. 400–405). The editor is of opinion that this little work is a fragment of a larger one.

- A philosophical commentary on Genesis, in two books, one of which deals with Genesis i. 20.

Attributed works

Eliakim Carmoly ("Ẓiyyon," i. 46) concludes that the Isaac who was so violently attacked by Abraham ibn Ezra in the introduction to his commentary on the Pentateuch, and whom he calls in other places "Isaac the Prattler", and "Ha-Yiẓḥaḳ," was none other than Isaac Israeli. But if Israeli was attacked by Ibn Ezra he was praised by other Biblical commentators, such as Jacob b. Ruben, a contemporary of Maimonides, and by Ḥasdai.

Another work which has been ascribed to Israeli, and which more than any other has given rise to controversy among later scholars, is a commentary on the "Sefer Yeẓirah." Steinschneider (in his "Al-Farabi," p. 248) and Carmoly (in Jost's "Annalen," ii. 321) attribute the authorship to Israeli, because Abraham ibn Ḥasdai (see above), and Jedaiah Bedersi in his apologetical letter to Solomon ben Adret ("Orient, Lit." xi. cols. 166-169) speak of a commentary by Israeli on the "Sefer Yeẓirah," though by some scholars the words "Sefer Yeẓirah" are believed to denote simply the "Book of Genesis." But David Kaufmann ("R. E. J." viii. 126), Sachs ("Orient, Lit." l.c.), and especially Grätz (Geschichte v. 237, note 2) are inclined to attribute its authorship to Israeli's pupil Dunash ibn Tamim.

Notes

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. 2, "Correspondence Theory of Truth", auth.: Arthur N. Prior, Macmillan, 1969, pp. 223–4.

- Jacquart and Micheau, "La Médecine Arabe et l'Occident Médiéval", Paris: Editions Maisonneuve et Larose, 1990, p.114

- Stern, "Biographical note", pp. xxiii-xxiv

- Stern, "Biographical note", p. xxv.

- Missori, Paolo; Brunetto, Giacoma M.; Domenicucci, Maurizio (7 February 2012). "Origin of the Cannula for Tracheotomy During the Middle Ages and Renaissance". World Journal of Surgery. 36 (4): 928–934. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1435-1. PMID 22311135.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Richard Gottheil and Max Seligsohn (1901–1906). "Israeli, Issac ben Solomon". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Richard Gottheil and Max Seligsohn (1901–1906). "Israeli, Issac ben Solomon". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Stern, S. M. (2009) [1958]. "Biographical note". In Alexander Altmann (ed.). Isaac Israeli: A Neoplatonic Philosopher of the Early Tenth Century. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. pp. xxiii–xxix. ISBN 0-226-01613-7.

Further reading

- Altmann, Alexander; Stern, Samuel Miklos (2009) [1958]. Isaac Israeli: A Neoplatonic Philosopher of the Early Tenth Century. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-01613-7.

- Older sources

- Jewish Encyclopedia bibliography: Ibn Abi Usaibia, Uyun al-Anba, ii. 36, 37, Bulak, 1882;

- 'Abd al-Laṭif, Relation de l'Egypte (translated by De Sacy), pp. 43, 44, Paris, 1810;

- Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, Literaturgesch. der Araber, iv. 376 (attributing to Israeli the authorship of a treatise on the pulse);

- Wüstenfeld, Geschichte der Arabischen Aerzte, p. 51;

- Sprenger, Geschichte der Arzneikunde, ii. 270;

- Leclerc, Histoire de la Médecine Arabe, i. 412;

- Eliakim Carmoly, in Revue Orientale, i. 350-352;

- Heinrich Grätz, Geschichte 3d ed., v. 257;

- Haji Khalfa, ii. 51, v. 41, et passim;

- Moritz Steinschneider, Cat. Bodl. cols. 1113-1124;

- idem, Hebr. Bibl. viii. 98. xii. 58;

- Dukes, in Orient, Lit. x. 657;

- Gross, in Monatsschrift, xxviii. 326: Jost's Annalen, i. 408.

External links

- Isaac Israeli, Stanford University.