Córdoba, Spain

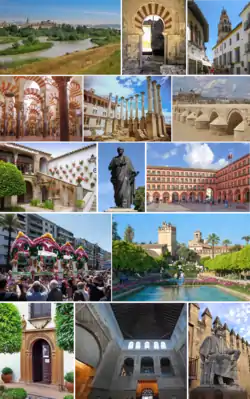

Córdoba (/ˈkɔːrdəbə/; Spanish: [ˈkoɾðoβa]),[lower-alpha 1] or Cordova (/ˈkɔːrdəvə/)[7][8] in English, is a city in Andalusia, southern Spain, and the capital of the province of Córdoba. It is the largest city in the province, 3rd largest in Andalusia, after Sevilla and Málaga, and the 12th largest in Spain. It was a Roman settlement, taken over by the Visigoths, followed by the Muslim conquests in the eighth century and later becoming the capital of the Caliphate of Córdoba. The city served as the capital in exile of the Umayyad Caliphate and other emirates. During these Muslim periods, Córdoba was transformed into a world leading center of education and learning, producing figures such as Averroes, Ibn Hazm, and Al-Zahrawi,[9][10] and by the 10th century it had grown to be the second-largest city in Europe.[11][12] It was conquered by the Kingdom of Castile through the Christian Reconquista in 1236.

Córdoba

Cordova | |

|---|---|

| |

Flag .svg.png.webp) Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): The City Of World Heritages[1] | |

Córdoba Location of Córdoba in Spain  Córdoba Córdoba (Andalusia)  Córdoba Córdoba (Province of Córdoba (Spain)) | |

| Coordinates: 37°53′4.226″N 4°46′46.443″W | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous community | |

| Province | Córdoba |

| Comarca | Córdoba |

| Judicial district | Córdoba |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council government |

| • Body | Ayuntamiento de Córdoba |

| • Mayor | José María Bellido[2] (PP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,253 km2 (484 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 106 m (348 ft) |

| Population (2018)[4] | |

| • Total | 325,708 |

| • Density | 260/km2 (670/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | Cordoban,[5] (Spanish: cordobés/sa, cordobense, cortubí, patriciense) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 14001–14014 |

| Official language | Spanish |

| Website | www |

Córdoba is home to notable examples of Moorish architecture such as The Mezquita-Catedral, which was named as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984 and is now a cathedral. The UNESCO status has since been expanded to encompass the whole historic centre of Córdoba, Medina-Azahara and Festival de los Patios. Cordoba has more World Heritage Sites than anywhere in the world, with four.[13] Much of this architecture, such as the Alcázar and the Roman bridge has been reworked or reconstructed by the city's successive inhabitants.

Córdoba has the highest summer temperatures in Spain and Europe, with average high temperatures around 37 °C (99 °F) in July and August.[14]

Etymology

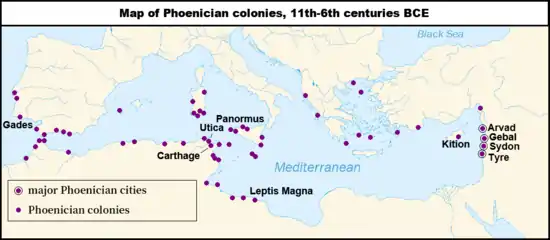

The name Córdoba has attracted a number of fanciful explanations. One is that the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca named the city Kart-Juba, meaning "the City of Juba," a Numidian commander who had died in a battle nearby. Another, suggested in 1799 by José Antonio Conde, is that the name comes from a Phoenician-Punic word qrt ṭwbh meaning 'good town'. Modern scholarship has dismissed these suggestions, concluding that the word originated in Old Iberian, a language about which little is known today: the second part of the name is the same as in the Iberian name Salduba (one used of the places now known as Saragossa and Marbella. After the Roman conquest, the town's name was Latinised as Corduba.[15]

History

Prehistory, antiquity and Roman foundation of the city

The first traces of human presence in the area are remains of a Neanderthal Man, dating to c. 42,000 to 35,000 BC.[16] Pre-urban settlements around the mouth of the Guadalquivir river are known to have existed from the 8th century BC. The population gradually learned copper and silver metallurgy. The first historical mention of a settlement dates to the Carthaginian expansion across the Guadalquivir. Córdoba was conquered by the Romans in 206 BC.

In 169 Roman consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus, grandson of Marcus Claudius Marcellus, who had governed both Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior, respectively), founded a Latin colony alongside the pre-existing Iberian settlement.[17] The date is contested; it could have been founded in 152. Between 143 and 141 BC the town was besieged by Viriatus. A Roman forum is known to have existed in the city in 113 BC.[18] The famous Cordoba Treasure, with mixed local and Roman artistic traditions, was buried in the city at this time; it is now in the British Museum.[19]

Corduba became a Roman colonia with the name Colonia Patricia,[20] between 46 and 45 BC. It was sacked by Caesar in 45 because of its fealty to Pompey, and resettled with veteran soldiers by Augustus. It became the capital of Baetica, with a forum and numerous temples, and was the main center of Roman intellectual life in Hispania Ulterior.[21][17] The Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger, his father, the orator Seneca the Elder, and his nephew, the poet Lucan came from Roman Cordoba.[22]

In the late Roman period, Corduba's bishop Hosius (Ossius) was the dominant figure of the western Church throughout the earlier 4th cent.[17] Later, Corduba occupied an important place in the Provincia Hispaniae of the Byzantine Empire (552–572) and under the Visigoths, who conquered it in the late 6th century.[23][24]

Umayyad rule

Córdoba was captured and mostly destroyed by the Muslims in 711 or 712.[25] Unlike other Iberian towns, no capitulation was signed and the position was taken by storm. Córdoba was in turn governed by direct Arab rule. The new Umayyad commanders established themselves within the city and in 716 it became a provincial capital,[25] subordinate to the Caliphate of Damascus; in Arabic it was known as قرطبة (Qurṭuba).

Different areas were allocated for services in the Saint Vincent Church shared by Christians and Muslims, until construction of the Córdoba Mosque started on the same spot under Abd-ar-Rahman I. Abd al-Rahman allowed the Christians to rebuild their ruined churches and purchased the Christian half of the church of St Vincent. In May 766 Córdoba was chosen as the capital of the independent Umayyad emirate, later caliphate, of al-Andalus. By 800 the megacity of Córdoba supported over 200,000 residents, 0.1 per cent of the global population. During the apogee of the caliphate (1000 AD), Córdoba had a population of about 400,000 inhabitants,.[12] In the 10th and 11th centuries Córdoba was one of the most advanced cities in the world, and a great cultural, political, financial and economic centre.[26][27][28] The Great Mosque of Córdoba dates back to this time. After a change of rulers the situation changed quickly. The vizier al-Mansur–the unofficial ruler of al-Andalus from 976 to 1002—burned most of the books on philosophy to please the Moorish clergy; most of the others were sold off or perished in the civil strife not long after.[29]

Córdoba had a prosperous economy, with manufactured goods including leather, metal work, glazed tiles and textiles, and agricultural produce including a range of fruits, vegetables, herbs and spices, and materials such as cotton, flax and silk.[29] It was also famous as a centre of learning, home to over 80 libraries and institutions of learning,[26][30] with knowledge of medicine, mathematics, astronomy, botany far exceeding the rest of Europe at the time.[29]

In 1002 Al-Mansur was returning to Córdoba from an expedition in the area of Rioja when he died. His death was the beginning of the end of Córdoba. Abd al-Malik al-Muzaffar, al-Mansur's older son, succeeded to his father’s authority, but he died in 1008, possibly assassinated. Sanchuelo, Abd al-Malik’s younger brother succeeded him. While Sanchuelo was away fighting Alfonso V of Leon, a revolution made Mohammed II al-Mahdi the Caliph. Sanchuelo sued for pardon but he was killed when he returned to Cardova. The slaves revolted against Mahdi, killed him in 1009, and replaced him with Hisham II in 1010. Hisham II kept a male harem and was forced out of office. In 1012 the Berbers "sacked Cardova." In 1016 the slaves captured Cardova and searched for Hisham II, but he had escaped to Asia. This event was followed by a fight for power until Hisham III, the last of the Umayyads, was routed from Córdoba in 1031.[31]

High Middle Ages

As the caliphate collapsed, so did Córdoba's economic and political hegemony, and it subsequently became part of the Taifa of Córdoba.[32]

In 1070, forces from the Taifa of Seville (ruled by Al-Mu'tamid) entered Córdoba to help in the defence of the city, that had been besieged by Al-Mamun, ruler of Toledo, yet they took control and expelled the last ruler of the taifa of Córdoba, Abd-Al Malik, forcing him to exile.[33] Al-Mamun did not cease in his efforts to take the city, and making use of a Sevillian renegade who murdered the Abbadid governor, he triumphantly entered the city on 15 February 1075, only to die there barely five months later, apparently poisoned.[34] Córdoba was seized by force in March 1091 by the Almoravids.[35]

Sworn enemies of the almohads, Ibn Mardanīš (the "Wolf King") and his stepfather Ibrahim Ibn Hamusk allied with Alfonso VIII of Castile and laid siege on Córdoba by 1158–1160, ravaging the surroundings but failing to take the place.[36]

Almohad caliph Abdallah al-Adil reshuffled governor Al-Bayyasi (brother of Zayd Abu Zayd, governor of Valencia) from Seville to Córdoba in 1224, only to see the latter became independent from Caliphal rule.[37][38] Al-Bayyasi asked Ferdinand III of Castile for help and Córdoba revolted against him.[39] Years later, in 1229, the city submitted to the authority of Ibn Hud,[40] disavowing him in 1233, joining instead the territories under Muhammad Ibn al-Aḥmar,[41] ruler of Arjona and soon-to-be emir of Granada.

Late Middle Ages

Ferdinand III of Castile entered the city on 29 June 1236, following a siege of several months. According to Arab sources, Córdoba fell on 23 Shawwal 633 (that is, on 30 June 1236, a day later than Christian tradition).[42] The conquest was followed by the return to Santiago de Compostela of the church bells that had been looted by Almanzor and moved to Córdoba by Christian war prisoners in the late 10th century.[43] Ferdinand III granted the city a fuero in 1241;[44] it was based on the Liber Iudiciorum and in the customs of Toledo, yet formulated in an original way.[45] The city was divided into 14 colaciones, and numerous new church buildings were added. The centre of the mosque was converted into a large Catholic cathedral.

Modern history

._Anton_van_den_Wyngaerde.jpg.webp) Panoramics of Córdoba as drawn by Anton van den Wyngaerde in 1567

Panoramics of Córdoba as drawn by Anton van den Wyngaerde in 1567

In the context of the Early Modern Period, the city experienced a golden age between 1530 and 1580, profiting from an economic activity based on the trade of agricultural products and the preparation of clothes originally from Los Pedroches, peaking at a population of about 50,000 by 1571.[46] A period of stagnation and ensuing decline followed.[46]

It was reduced to 20,000 inhabitants in the 18th century. The population and economy started to increase again only in the early 20th century.

The second half of the 19th century saw the arrival of railway transport via the opening of the Seville–Córdoba line on 2 June 1859.[47] Córdoba became connected by railway to Jerez and Cádiz in 1861 and, in 1866, following the link with Manzanares, with Madrid.[48] The city was also eventually connected to Málaga and Belmez.[49]

On 18 July 1936, the military governor of the province, Col.Ciriaco Cascajo, launched the Nationalist coup in the city, bombing the civil government and arresting the civil governor, Rodríguez de León;[50] these actions ignited the Spanish Civil War. Following the orders of the putschist General Queipo de Llano, he declared a state of war. The putschists were met by the resistance of the political and social representatives who had gathered in the civil government headquarters,[51] and remained there until the Nationalist rifle fire and the presence of artillery broke their morale. When its defenders began fleeing the building, Rodríguez de León finally decided to surrender and was arrested.[52] In the following weeks, Queipo de Llano and Major Bruno Ibañez carried out a bloody repression in which 2,000 persons were executed.[53][54][55] The ensuing Francoist repression in wartime and in the immediate post-war period (1936–1951) is estimated to have led to around 9,579 killings in the province.[56]

Córdoba was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site on 17 December 1984, but the city has a number of modern areas, including the district of Zoco and the area surrounding the railway station.

The regional government (the Junta de Andalucía) has for some time been studying the creation of a Córdoba Metropolitan Area that would comprise, in addition to the capital itself, the towns of Villafranca de Córdoba, Obejo, La Carlota, Villaharta, Villaviciosa, Almodóvar del Río and Guadalcázar. The combined population of such an area would be around 351,000. The Plano de Córdoba was also known for its books and how they created it.

Geography

Location

Córdoba is located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in the depression formed by the Guadalquivir river, that cuts across the city in a east-north east to west-south west direction. The wider municipality extends across an area of 1,254.25 km2,[57] making it the largest municipality in Andalusia and the fourth largest in Spain.[58]

The city of Córdoba lies in the middle course of the river. Three major landscape units in the municipality include the Sierra (as in the southern reaches of Sierra Morena), the Valley proper and the Campiña.[59]

The differences in elevation in the Valley are very small, ranging from 100 and 170 metres above sea level,[59] with the city proper located at an average altitude of roughly 125 metres above sea level.[60] The landscape of the valley is further subdivided in the piedmont connecting with the Sierra, the fluvial terraces and the most immediate vicinity of the river course.[59]

The Miocene Campiña, located in the southern bank of the Guadalquivir, features a hilly landscape gently increasing in height up to about 200 m.[60] In the Sierra, to the north of the city, the altitude increases relatively abruptly up to 500 meters.[60] Both the Sierra and the Campiña display viewpoints over the valley.[59]

Climate

Córdoba has a hot Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa).[61] It has the highest summer average daily temperatures in Europe (with highs averaging 36.9 °C (98 °F) in July) and days with temperatures over 40 °C (104 °F) are common in the summer months. August's 24-hour average of 28.0 °C (82 °F) is also one of the highest in Europe, despite relatively cool nightly temperatures.

Winters are mild, yet cooler than other low lying cities in southern Spain due to its interior location, wedged between the Sierra Morena and the Penibaetic System. Precipitation is concentrated in the coldest months; this is due to the Atlantic coastal influence. Precipitation is generated by storms from the west that occur most frequently from December to February. This Atlantic characteristic then gives way to a hot summer with significant drought more typical of Mediterranean climates. Annual rain surpasses 600 mm (24 in), although it is recognized to vary from year to year.

The registered maximum temperature at the Córdoba Airport, located at 6 kilometres (4 miles) from the city, was 46.9 °C (116.4 °F) on 13 July 2017. The lowest registered temperature was −8.2 °C (17.2 °F), on 28 January 2005.[62]

| Climate data for Córdoba (1981-2010), extremes (1949-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.9 (73.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

41.2 (106.2) |

45.0 (113.0) |

46.9 (116.4) |

46.2 (115.2) |

45.4 (113.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

29.7 (85.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

46.9 (116.4) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

28.2 (82.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

35.2 (95.4) |

40.4 (104.7) |

42.5 (108.5) |

42.0 (107.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

43.1 (109.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.9 (98.4) |

36.5 (97.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

1.8 (35.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.2 (17.2) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

0.2 (32.4) |

2.4 (36.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 66 (2.6) |

55 (2.2) |

49 (1.9) |

55 (2.2) |

40 (1.6) |

13 (0.5) |

2 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

35 (1.4) |

86 (3.4) |

80 (3.1) |

111 (4.4) |

605 (23.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 7 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 57 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 71 | 64 | 60 | 55 | 48 | 41 | 43 | 52 | 66 | 73 | 79 | 60 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 174 | 186 | 218 | 235 | 289 | 323 | 363 | 336 | 248 | 205 | 180 | 148 | 2,905 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[62] | |||||||||||||

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

Córdoba has the second largest Old town in Europe, the largest urban area in the world declared World Heritage by UNESCO.

Roman

The Roman Bridge, over the Guadalquivir River, links the area of Campo de la Verdad with Barrio de la Catedral. It was the only bridge of the city for twenty centuries, until the construction of the San Rafael Bridge in the mid-20th century. Built in the early 1st century BC, during the period of Roman rule in Córdoba, probably replacing a more primitive wooden one, it has a length of about 250 m and has 16 arches.

Other Roman remains include the Roman Temple, the Theatre, Mausoleum, the Colonial Forum, the Forum Adiectum, an amphitheater and the remains of the Palace of Emperor Maximian in the archaeological site of Cercadilla.

Islamic

Great Mosque of Córdoba

From 784- 786 AD, Abd al-Rahman I built the Mezquita, or Great Mosque, of Córdoba, in the Umayyad style of architecture with variations inspired by indigenous Roman and Christian Visigothic structures. Later caliphs extended the mosque with more domed bays, arches, intricate mosaics and a minaret, making it one of the four wonders of the medieval Islamic world. After the Christian reconquest of Andalucía, a cathedral was built in the heart of the mosque, however much of the original structure remains. It can be found in the Historic Centre of Córdoba, a recognized World Heritage Site.[63][64][65][66]

Minaret of San Juan

Built in 930 AD, the mosque that this minaret adorned has been replaced by a church and the minaret re-purposed as a tower. Even so, it retains the characteristics of Islamic architecture in the region, including two ornamental arches.[65][67]

Mills of the Guadalquivir

Along the banks of the Guadalquivir are the Mills of the Guadalquivir, Moorish-era buildings that used the water flow to grind flour. They include the Albolafia, Alegría, Carbonell, Casillas, Enmedio, Lope García, Martos, Pápalo, San Antonio, San Lorenzo and San Rafael mills.[68]

Medina Azahara

On the outskirts of the city lies the archaeological site of the city of Medina Azahara, which, together with the Alhambra in Granada, is one of the main examples of Spanish-Muslim architecture in Spain.

Caliphal Baths

Near the stables are located, along the walls, the medieval Baths of the Umayyad Caliphs.

Jewish Quarter

.jpg.webp)

Near the cathedral is the old Jewish quarter, which consists of many irregular streets, such as Calleja de las Flores and Calleja del Pañuelo, and which is home to the Synagogue and the Sephardic House.

Christian

Surrounding the large Old town are the Roman walls: gates include the Puerta de Almodóvar, the Puerta de Sevilla and Puerta del Puente, which are the only three gates remaining from the original thirteen. Towers and fortresses include the Malmuerta Tower, Torre de Belén and the Puerta del Rincón's Tower.

In the south of the Old town and east of the great cathedral, in the Plaza del Potro, is the Posada del Potro, a row of inns mentioned in literary works including Don Quixote and La Feria de los Discretos, and which remained active until 1972. Both the plaza and the inn get their name from the fountain in the centre of the plaza, which represents a foal (potro). Not far from this plaza is the Arco del Portillo (a 14th-century arch). In the extreme southwest of the Old Town is the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos, a former royal property and the seat of the Inquisition; adjacent to it are the Royal Stables, where Andalusian horses are bred. Palace buildings in the Old Town include the Palacio de Viana (14th century) and the Palacio de la Merced among others. Other sights include the Cuesta del Bailío (a staircase connecting the upper and lower part of the city).

Fernandine churches

The city is home to 12 Christian churches that were built (many as transformations of mosques) by Ferdinand III of Castile after the reconquest of the city in the 13th century. They were to act both as churches and as the administrative centres in the neighborhoods into which the city was divided in medieval times. Some of those that remain are:

- San Nicolás de la Villa.

- San Miguel.

- San Juan y Todos los Santos (also known as Iglesia de la Trinidad).

- Santa Marina de Aguas Santas.

- San Agustín. Begun in 1328, it has now an 18th-century appearance. The façade bell tower, with four bells, dates to the 16th century.

- San Andrés, largely renovated in the 14th and 15th centuries. It has a Renaissance portal (1489) and a bell tower from the same period, while the high altar is a Baroque work by Pedro Duque Cornejo.

- San Lorenzo.

- Church of Santiago.

- San Pedro.

- Santa María Magdalena. Like the others, it combines Romanesque, Mudéjar and Gothic elements.

- San Pablo. In the church's garden in the 1990s the ruins of an ancient Roman circus were discovered.[69]

Other religious structures

- Iglesia de San Hipólito. It houses the tombs of Ferdinand IV and Alfonso XI of Castile, kings of Castile and León.

- Iglesia de San Francisco

- Iglesia de San Salvador y Santo Domingo de Silos

- Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Linares

- Torre de Santo Domingo de Silos

- Santuario de Nuestra Señora de la Fuensanta

- Chapel of San Bartolomé

- Convent of Santa Clara

- Convent of Santa Cruz

- Convent of Santa Marta

Sculptures and memorials

Scattered throughout the city are ten statues of the Archangel Raphael, protector and custodian of the city. These are called the Triumphs of Saint Raphael, and are located in landmarks such as the Roman Bridge, the Puerta del Puente and the Plaza del Potro.

In the western part of the Historic Centre are the statue of Seneca (near the Puerta de Almodóvar, a gate from the time of Islamic rule, (the Statue of Averroes (next to the Puerta de la Luna), and Maimonides (in the plaza de Tiberiades). Further south, near the Puerta de Sevilla, are the sculpture to the poet Ibn Zaydún and the sculpture of the writer and poet Ibn Hazm and, inside the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos, the monument to the Catholic Monarchs and Christopher Columbus.

There are also several sculptures in plazas of the Old Town. In the central Plaza de las Tendillas is the equestrian statue of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, in the Plaza de Capuchinos is the Cristo de los Faroles, in Plaza de la Trinidad is the statue of Luis de Góngora, in the Plaza del Cardenal Salazar is the bust of Ahmad ibn Muhammad abu Yafar al-Gafiqi, in the Plaza de Capuchinas is the statue to the bishop Osio, in Plaza del Conde de Priego is the monument to Manolete and the Campo Santo de los Mártires is a statue to Al-Hakam II and the monument to the lovers.

In the Jardines de la Agricultura is the monument to the painter Julio Romero de Torres, a bust by sculptor Mateo Inurria, a bust of the poet Julio Aumente and the sculpture dedicated to the gardener Aniceto García Roldán, who was killed in the park. Further south, in the Gardens of the Duke of Rivas, is a statue of writer and poet Ángel de Saavedra, 3rd Duke of Rivas by sculptor Mariano Benlliure.

In the Guadalquivir river, near the San Rafael Bridge is the Island of the sculptures, an artificial island with a dozen stone sculptures executed during the International Sculpture Symposium. Up the river, near the Miraflores bridge, is the "Hombre Río", a sculpture of a swimmer looking to the sky and whose orientation varies depending on the current.

Bridges

- San Rafael Bridge, consisting of eight arches of 25 m span and a length of 217 m. The width is between parapets, divided into 12 m of cobblestone for four circulations and two tiled concrete sidewalks. It was inaugurated on 29 April 1953 joining the Avenue Corregidor with Plaza de Andalucía. In January 2004 the plaques reading "His Excellency the Head of State and Generalissimo of all the Armies, Francisco Franco Bahamonde, opened this bridge of the Guadalquivir on 29 April 1953", which were on both sides of each of the entrances of the bridge, were removed.

- Andalusia Bridge, a suspension bridge.

- Puente de Miraflores, known as "the rusty bridge". This bridge links the Street San Fernando and Ronda de Isasa with the Miraflores peninsula. It was designed by Herrero, Suárez and Casado and inaugurated on 2 May 2003. At first, in 1989, a proposal by architect-engineer Santiago Calatrava was considered[70] that would look like the Lusitania Bridge of Mérida, but this was eventually discarded because its height would obscure the view of the Great Mosque.

- Autovía del Sur Bridge.

- Abbas Ibn Firnas Bridge, Inaugurated in January 2011 It is part of the variant west of Córdoba.

- Puente del Arenal, connecting Avenue Campo de la Verdad with the Recinto Ferial (fairground) of Cordoba.

Gardens, parks and natural environments

- Jardines de la Victoria. Within the gardens there are two newly renovated facilities, the old Caseta del Círculo de la Amistad, today Caseta Victoria, and the Kiosko de la música, as well as a small Modernist fountain from the early 20th century. The northern section, called Jardines of Duque de Rivas, features a pergola of neoclassical style, designed by the architect Carlos Sáenz de Santamaría; it is used as an exhibition hall and a café bar.

- Jardines de la Agricultura, located between the Jardines de la Victoria and the Paseo de Córdoba: it includes numerous trails that radially converge to a round square which has a fountain or pond. This is known as the duck pond, and, in the centre, has an island with a small building in which these animals live. Scattered throughout the garden are numerous sculptures such as the sculpture in memory of Julio Romero de Torres, the sculpture to the composer Julio Aumente and the bust of Mateo Inurria. In the north is a rose garden in form of a labyrinth.

- Parque de Miraflores, located on the south bank of the river Guadalquivir. It was designed by the architect Juan Cuenca Montilla as a series of terraces. Among other points of interest as the Salam and Miraflores Bridge and a sculpture by Agustín Ibarrola.

- Parque Cruz Conde, located southwest of the city, is an open park and barrier-free park in English gardens style.[71]

- Paseo de Cordoba. Located on the underground train tracks, it is a long tour of several km in length with more than 434,000 m². The tour has numerous fountains, including six formed by a portico of falling water which form a waterfall to a pond with four levels. Integrated into the tour is a pond of water from the Roman era, and the building of the old train station of RENFE, now converted into offices of Canal Sur.

- Jardines Juan Carlos I, in the Ciudad Jardín neighborhood. It is a fortress which occupies an area of about 12,500 square metres.

- Jardines del Conde de Vallellano, located on both sides of the avenue of the same name. It includes a large L-shaped pond with a capacity of 3,000 m3 (105,944.00 cu ft) and archaeological remains embedded in the gardens, among which is a Roman cistern from the second half of the 1st century BC.

- Parque de la Asomadilla, with a surface of 27 hectares, is the second largest park in Andalusia.[72] The park recreates a Mediterranean forest vegetation, such as hawthorn, pomegranate, hackberry, oak, olive, tamarisk, cypress, elms, pines, oaks and carob trees among others.

- Balcón del Guadalquivir.

- Jardines de Colón.

- Sotos de la Albolafia. Declared Natural monument by the Andalusian Autonomous Government, it is located in a stretch of the Guadalquivir river from the Roman Bridge and the San Rafael Bridge, with an area of 21.36 hectares.[73] Host a large variety of birds and is an important point of migration for many birds.

- Parque periurbano Los Villares.

Museums

The Archaeological and Ethnological Museum of Córdoba is a provincial museum located near the Guadalquivir River.[74] The museum was officially opened in 1867 and shared space with the Museum of Fine Arts until 1920. In 1960, the museum was relocated to the Renaissance Palace of Páez de Castillo where it remains to present day. The Archaeological and Ethnological Museum has eight halls which contain pieces from the middle to late bronze age, to Roman culture, Visigothic art, and Islamic culture.[75]

The Julio Romero de Torres Museum is located next to the Guadalquivir river and was opened in November 1931.[76] The home of Julio Romero de Torres, has undergone many renovations and been turned into a museum and it has also been home to several other historical institutions such as the Archaeological Museum (1868-1917) and the Museum of Fine Arts. Many of the works include paintings and motifs done by Julio Romero de Torres himself.[77]

The Museum of Fine Arts is located next to the Julio Romero de Torres Museum which it shares a courtyard with.[78] The building originally was for the old Hospital for Charity but after that the building went under many renovations and renewals to become the renaissance style building it is today.[79][80] The Museum of Fine Arts contains many works from the baroque period, medieval renaissance art, work from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, drawings, mannerist art and other unique works.[81]

The Diocesan Museum is located in the Episcopal Palace, Cordoba which was built upon a formerly Arabic castle. The collection within houses many paintings, sculptures and furniture.[82]

Other notable museums within Córdoba:

- The Arab Baths of the Fortress Califal

- Botanical Museum of Cordova

- Three Cultures Museum

- Bullfighting Museum

- Molino de Martos Hydraulic Museum

- Museo Palacio de Viana

Festivals

Tourism is especially intense in Córdoba during May as this month hosts three of the most important annual festivals in the city:[83]

- Las Cruces de Mayo (The May Crosses of Córdoba).[84] This festival takes place at the beginning of the month. During three or four days, crosses of around 3m height are placed in many squares and streets and decorated with flowers and a contest is held to choose the most beautiful one. Usually there is regional food and music near the crosses.

- Los Patios de Córdoba (The Courtyards Festival of Córdoba - World Heritage).[85] This festival is celebrated during the second and third week of the month. Many houses of the historic center open their private patios to the public and compete in a contest. Both the architectonic value and the floral decorations are taken into consideration to choose the winners. It is usually very difficult and expensive to find accommodation in the city during the festival.

- La Feria de Córdoba (The Fair of Córdoba).[86] This festival takes place at the end of the month and is similar to the better known Seville Fair with some differences, mainly that the Sevilla Fair has majority private casetas (tents run by local businesses), while the Córdoba Fair has majority public ones.

Politics and government

- Local administration

As of 2019 José María Bellido Roche (PP) is the mayor of Córdoba.

The City Council of Córdoba is divided into different areas: the Presidency; Human Resources, Management, Tax and Public Administration; City Planning, Infraestructure, and Environment; Social; and Development.[87] The Council holds regular plenary sessions once a month, but can hold extraordinary plenary session to discuss issues and problems affecting the city.[88]

The Governing Board, chaired by the mayor, consists of four IU councillors, three of PSOE, and three non-elected members.[89][90] The municipal council consists of 29 members: 11 of PP, 7 of PSOE, 4 of IU, 4 of Ganemos Córdoba, 2 of Ciudadanos and 1 of Unión Cordobesa.

| Legislature | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 1979–1983 | Julio Anguita | PCE |

| 1983–1987 | Julio Anguita (until 1 February 1986) | PCE |

| Herminio Trigo | IU | |

| 1987–1991 | Herminio Trigo | IU |

| 1991–1995 | Herminio Trigo | IU |

| Manuel Pérez Pérez | IU | |

| 1995–1999 | Rafael Merino | PP |

| 1999–2003 | Rosa Aguilar | IU |

| 2003–2007 | Rosa Aguilar | IU |

| 2007–2011 | Rosa Aguilar (until 23 April 2009) | IU |

| Andrés Ocaña | IU | |

| 2011–2015 | José Antonio Nieto Ballesteros | PP |

| 2015-2019 | Isabel Ambrosio Palos | PSOE |

| 2019- | José María Bellido Roche | PP |

- Administrative divisions

As of July 2008, the city is divided into 10 administrative districts, coordinated by the Municipal district boards, which in turn are subdivided into neighbourhoods:

| District | District | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Centro | Poniente-Sur |  |

| Levante | Sur | |

| Noroeste | Sureste | |

| Norte-Sierra | Periurbano Este-Campiña | |

| Poniente-Norte | Periurbano Oeste-Sierra |

Notable people

- Abd Allah al-Qaysi - Islamic jurist

- Vicente Amigo - Flamenco artist

- Averroes - Islamic philosopher

- Joaquín Cortés - Flamenco artist

- Gabi Delgado-López - musician

- Fosforito - Flamenco artist

- Luis de Góngora - Renaissance-era poet

- Ibn Hazm - Islamic theologian and jurist

- Ibn Maḍāʾ - Islamic linguist

- Lucan - Roman poet

- Maimonides - Jewish philosopher and rabbi

- Manolete - matador

- Juan de Mena - Medieval poet

- Mundhir bin Sa'īd al-Ballūṭī - Islamic jurist

- Paco Peña - Flamenco artist

- al-Qurtubi - jurist of the Maliki school

- Julio Romero de Torres - painter

- Seneca, Stoic philosopher

- Juan Serrano - Flamenco artist

- Fernando Tejero - actor

- Hisae Yanase - artist[91]

Sports

Córdoba's main sports team is its association football team, Córdoba CF, which plays in the Spanish Segunda División B following a brief one-season tenure in La Liga during the 2014-15 season. Home matches are played at the Estadio Nuevo Arcángel, which has 20,989 seats.

Córdoba also has a professional futsal team, Córdoba Patrimonio de la Humanidad, which plays in the Primera División de Futsal.[92] The local youth basketball club, CD Cordobasket, had a professional team which played in the Liga EBA for three seasons before going on hiatus in August 2019.[93] The futsal team plays the majority of its home games at the 3,500 seat Palacio Municipal de Deportes Vista Alegre.

Transport

Rail

Córdoba railway station is connected by high speed trains to the following Spanish cities: Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, Málaga and Zaragoza. More than 20 trains per day connect the downtown area, in 54 minutes, with Málaga María Zambrano station, which provides interchange capability to destinations along the Costa del Sol, including Málaga Airport.

Airports

Córdoba has an airport, although there are no airlines operating commercial flights on it. The closest airports to the city are Seville Airport (110 km as the crow flies), Granada Airport (118 km) and Málaga Airport (136 km).[94][95]

Road

The city is also well connected by highways with the rest of the country and Portugal.

Intercity buses

The main bus station is located next to the train station. Several bus companies operate intercity bus services to and from Cordoba.[94]

Gallery

Parque de Miraflores..

Parque de Miraflores...jpg.webp) Paseo de Córdoba.

Paseo de Córdoba..jpg.webp) Fuente de los Jardines de Colón.

Fuente de los Jardines de Colón..jpg.webp) Gardens of the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos.

Gardens of the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos..jpg.webp) Mosque–Cathedral.

Mosque–Cathedral..jpg.webp) Street scene in Santa Maria, Córdoba.

Street scene in Santa Maria, Córdoba. View of Córdoba from Puente Romano.

View of Córdoba from Puente Romano. Riverfront viewed from Puente Romano, Córdoba.

Riverfront viewed from Puente Romano, Córdoba.

Twin towns – sister cities

Kairouan, Tunisia (1968)

Kairouan, Tunisia (1968) Lahore, Pakistan (1968)

Lahore, Pakistan (1968) Córdoba, Argentina (1969)

Córdoba, Argentina (1969) Córdoba, Mexico (1980)

Córdoba, Mexico (1980) Bukhara, Uzbekistan (1983)

Bukhara, Uzbekistan (1983) Smara, Western Sahara (1987)

Smara, Western Sahara (1987) Fez, Morocco (1990)

Fez, Morocco (1990) Old Havana, Cuba (2000)

Old Havana, Cuba (2000) Damascus, Syria (2002)

Damascus, Syria (2002) Santiago de Compostela, Spain (2004)

Santiago de Compostela, Spain (2004) Nuremberg, Germany (2010)

Nuremberg, Germany (2010) Nîmes, France (2013)

Nîmes, France (2013)

References

- Citations

- "UNESCO World Heritages". worldatlas.com. World Atlas. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "El mapa de las nuevas alcaldías 2019-2023". El Mundo. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Extensión superficial, altitud y población de hecho de las provincias, capitales y municipios de más de 20.000 habitantes. Península, Islas Baleares y Canarias". Anuario 1996. 1996. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- "Cordoban". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Wettinger, G. (1989). "Malta fiz-zmien nofsani". In T. Cortis (ed.). L-identita' kulturali ta' Malta : kungress nazzjonali, 13-15 ta' April 1989 (PDF) (in Maltese). Valletta: Department of Information. pp. 207–223.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Córdoba (conventional Cordova)

- The Bible in Spain by George Borrow.

- Simon Barton (30 June 2009). A History of Spain. Macmillan International Higher Education. pp. 44–5. ISBN 978-1-137-01347-7.

- Francis Preston Venable (1894). A Short History of Chemistry. Heath. p. 21.

- Hareir, Idris El; Mbaye, Ravane (10 April 2011). The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231041532.

- J. Bradford De Long and Andrei Shleifer (October 1993), "Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolution" (PDF), The Journal of Law and Economics, 36 (2): 671–702 [678], CiteSeerX 10.1.1.164.4092, doi:10.1086/467294, S2CID 13961320, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2018, retrieved 27 October 2017

- Shivani Vora. "This city now has more UNESCO Heritage sites than anywhere in the world". CNN. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- "Standard climate values for Córdoba". Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- C. F. Seybold and M. Ocaña Jiménez, “Ḳurṭuba”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, ed. by P. Bearman and others, 2nd edn (Leiden: Brill, 1960-2007), doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_4552.

- "Neanderthals Died Out Earlier Than Thought". Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- Simon J. Keay (29 March 2012). "Corduba". In Simon Hornblower; Antony Spawforth; Esther Eidinow (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. OUP Oxford. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

- Vaquerizo, D. & Murillo, J. (2016). "The suburbs of Cordoba". Estoa. Revista de la Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo. 5 (9): 37–60, esp. p. 40. doi:10.18537/est.v005.n009.04. Retrieved 17 December 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Cordoba Treasure". The British Museum. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- John Pollini (20 November 2012). From Republic to Empire: Rhetoric, Religion, and Power in the Visual Culture of Ancient Rome. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 531. ISBN 978-0-8061-8816-4.

- Isaksen, Leif (21 March 2008). "The application of network analysis to ancient transport geography: A case study of Roman Baetica". Digital Medievalist. 4 (0). doi:10.16995/dm.20. ISSN 1715-0736.

- Simon J. Keay (29 March 2012). Simon Hornblower; Antony Spawforth; Esther Eidinow (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. OUP Oxford. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

- Norman Roth (1994). Jews, Visigoths, and Muslims in Medieval Spain: Cooperation and Conflict. BRILL. p. 7. ISBN 90-04-09971-9.

- Robin S. Doak (2009). Empire of the Islamic World. Infobase Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4381-0317-4.

- Roger Collins (17 February 1995). The Arab Conquest of Spain: 710 - 797. Wiley. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-631-19405-7.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- "Spain from the 6th to 12th Century History". Archived from the original on 18 October 2007.

- Amir Hussain, “Muslims, Pluralism, and Interfaith Dialogue,” in Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism, Omid Safi (ed.), p. 257 (Oneworld Publications, 2003).

- "Córdoba: Historical Overview". Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- "Muslim Spain (711-1492)". BBC. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- “10th C. Al-Andalus: Al-Mansur.” and Daniel Eisenberg, “Homosexuality” in Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia, ed. Michael Gerli (Routledge, 2003), 398. Archived 28 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine and J. B. Bury, The Cambridge Medieval History vol 3 - Germany and the Western Empire (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2011), 378-379.

- Josef W. Meri (31 October 2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0.

- Frochoso Sánchez, Rafael (2014). "Las monedas de los Banū Ŷahwar de Córdoba - 422 - 462 h. / 1031-1070d.C." (PDF). OMNI, Numismatic Journal. ISSN 2104-8363.

- Porres Martín-Cleto, Julio (1999). "La Dinastía de los Banu Di L-Nun de Toledo" (PDF). Tulaytula. Toledo: Asociación de Amigos del Toledo Islámico. III (4): 40.

- Coeña del Real, María Jesús (2011). "Los inicios de la hegemonía castellano-leonesa y la invasión almorávide" (PDF). Innovación y experiencias educativas (41): 5. ISSN 1988-6047.

- Cruz Aguilar, Emilio de la (1994). "El Reino Taifa de Segura" (PDF). Boletín del Instituto de Estudios Giennenses (153): 388. ISSN 0561-3590.

- Molina López 1986, p. 41.

- González Jiménez 2016, p. 207.

- Molina López, Emilio (1986). "Por una cronología histórica sobre el Šarq Al-Andalus (s. XIII)" (PDF). Sharq Al-Andalus. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante. Área de Estudios Árabes e Islámicos (3): 41. doi:10.14198/ShAnd.1986.3.05. ISSN 0213-3482.

- Molina López 1986, p. 43.

- Molina López 1986, p. 45.

- García Sanjuán, Alejandro (2016). "La conquista cristiana de Andalucía y el destino de la población musulmana (621-62 H/1224-64). La aportación de las fuentes árabes". In González Jiménez, Manuel; Sánchez Saus, Rafael (eds.). Arcos y el nacimiento de la frontera andaluza (1264-1330). Seville: Universidad de Sevilla; Universidad de Cádiz. p. 43.

- González Jiménez, Manuel (2014). "Fernando III y la repoblación de Andalucía". La Península Ibérica en tiempos de Las Navas de Tolosa (PDF). Madrid. p. 224. ISBN 978-84-941363-8-2.

- Mellado Rodríguez, Joaquín (2000). "El fuero de Córdoba: edición crítica y traducción". Arbor. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. CLXVI (654): 192. doi:10.3989/arbor.2000.i654.1011. ISSN 0210-1963.

- González Jiménez, Manuel (2001). "Fernando III El Santo, legislador" (PDF). Boletín de la Real Academia Sevillana de Buenas Letras: Minervae Baeticae (29): 115–116. ISSN 0214-4395.

- Villar Movellán 1998, p. 102.

- López Serrano 2017, p. 587.

- López Serrano 2017, p. 589.

- López Serrano 2017, pp. 593–597.

- Thomas, Hugh (2001). The Spanish Civil War. London: Modern Library. pp. 1096. ISBN 9780375755156.

- Ponce Alberca & García Bonilla 2008, p. 11.

- Ponce Alberca, Julio; García Bonilla, Jesús (2008). "Guerra y poder. Los gobernadores civiles en Andalucía (1936-1939)". Guerra, Franquismo y Transición. Los gobernadores civiles en Andalucía (1936-1979) (PDF). Seville: Centro de Estudios Andaluces. p. 11. ISBN 978-84-691-6712-0.

- Thomas 2001, p. 252.

- Thomas 2001, p. 253.

- Thomas 2001, p. 254.

- Cobo Romero, Francisco (2012). "Las cifras de la violencia institucional y las mecánicas represivas del franquismo en Andalucía". In Cobo Romero, Francisco (ed.). La represión franquista en Andalucía: Balance historiográfico, perspectivas teóricas y análisis de resultados (PDF). pp. 51–66. ISBN 9788493992606.

- "Datos del Registro de Entidades Locales". Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Burgueño & Guerrero Lladós 2014, p. 19.

- Torres Márquez 2013, p. 138.

- Domínguez Bascón 1995, p. 283.

- M. Kottek; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- "Valores climatológicos extremos. Córdoba" (in Spanish). Aemet.es. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Jayyusi, Salma Khadra (1994). The legacy of Muslim Spain (2nd ed.). Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 129–135. ISBN 978-9004099548.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Historic Centre of Cordoba". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Michell, George (2011) [1978]. Architecture of the Islamic world its history and social meaning; with a complete survey of key monuments. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 212. ISBN 9780500278475.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S. (2009). The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- "Minaret of San Juan". english.turismodecordoba.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Reina, Carmen (11 November 2014). "Los eternos jornaleros del Guadalquivir". El Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Discovery of a Roman Circus in Cordoba". Artencordoba.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- "Projects of Santiago Calatrava". Soloarquitectura.com. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- "Parque Cruz Conde" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 January 2009.

- Juan M. Niza (1 November 2005). "El parque de La Asomadilla se inicia con la apertura de pozos". Diario Córdoba (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 January 2010.

- Los Sotos de la Albolafia, Inventario de Humedales de Andalucía.

- TURESPAÑA (23 April 2007). "Museums in Spain: Cordoba Archaeological Museum in Córdoba, Spain | spain.info USA". Spain.info. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- "Archaeological and Ethnological Museum of Córdoba". ArtenCórdoba Guided Tours. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- "Mapa del Museo - Museo de Julio Romero de Torres | Visita Virtual". www.museojulioromero.cordoba.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Museum of Julio Romero de Torres, Córdoba". ArtenCórdoba Guided Tours. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- Abdulhameed, Ahmed M (2013). Discover Spain. Lulu Press. ISBN 9781447876564.

- "Fine Arts Museum". english.turismodecordoba.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Cordoba: Museum of Fine Arts, Cordoba". tripadvisor.com. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Museum of Fine Arts of Córdoba". ArtenCórdoba Guided Tours. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Diocesan Museum (Episcopal Palace)". english.turismodecordoba.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- "Cordoban May". Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "The May Crosses of Cordoba". Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "The Courtyards Festival of Cordoba - World Heritage". Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "The Fair of Cordoba". Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Áreas de Gobierno" [Areas of Governance]. Ayuntamiento de Córdoba (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- "Reglamento Orgánico General del Ayuntamiento de Córdoba" (PDF), B.O.P (in Spanish) (29), p. 1044, 2009, retrieved 13 February 2018

- "Junta de Gobierno Local" [Local Government Board]. Ayuntamiento de Córdoba [City Council of Córdoba] (in Spanish). 28 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012.

- Municipal Elections 2007 in Córdoba: Cargos en la Corporación Municipal – Article of Cordobapedia published in Castilian, GFDL license.

- Miranda, Luis (21 May 2019). "Muere Hisae Yanase, la artista japonesa que ancló su sonrisa en Córdoba". sevilla (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "El Córdoba Futsal será "Patrimonio de la Humanidad" en la nueva temporada". Mundo Deportivo. 29 July 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- prensa (8 August 2019). "Hasta pronto". Cordobasket (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- "Cordoba: Stations". Travelinho. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Aeropuerto Córdoba". Aena (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Las 12 hermanas de Córdoba". diariocordoba.com (in Spanish). Diario Córdoba. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Bibliography

- Burgueño, Jesús; Guerrero Lladós, Montse (2014). "El mapa municipal de España. Una caracterización geográfica". Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles (64). ISSN 0212-9426.

- Domínguez Bascón, Pedro (1995). "Inversiones de temperatura en el valle del Guadalquivir: un factor climático de gran influencia en el medio ambiente de la ciudad de Córdoba". Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense (15): 281–288. ISSN 0211-9803.

- López Serrano, Miguel Jesús (2017). "Los inicios del ferrocarril en la provincia de Córdoba. Una visión a corto plazo" (PDF). Anuario Jurídico y Económico Escurialense. San Lorenzo de El Escorial: Real Centro Universitario Escorial-María Cristina (50): 579–600. ISSN 1133-3677.

- Torres Márquez, Martín (2013). "Paisajes del Valle medio del Guadalquivir cordobés: Funcionalidad y cambios" (PDF). Revista de Estudios Regionales (96): 135–180. ISSN 0213-7585.

- Villar Movellán, Alberto (1998). "Esquemas urbanos de la Córdoba renacentista" (PDF). Laboratorio de Arte: Revista del Departamento de Historia del Arte. Seville: Universidad de Sevilla (11): 101–120. ISSN 1130-5762.

- Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- Arthur de Capell Brooke (1831), "Cordova", Sketches in Spain and Morocco, London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, OCLC 13783280

- Richard Ford (1855), "Cordova", A Handbook for Travellers in Spain (3rd ed.), London: J. Murray, OCLC 2145740

- John Lomas, ed. (1889), "Cordova", O'Shea's Guide to Spain and Portugal (8th ed.), Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black

- Published in the 20th century

- "Cordova". Spain and Portugal (3rd ed.). Leipzig: Karl Baedeker. 1908. OCLC 1581249.

- Trudy Ring, ed. (1996). "Cordoba". Southern Europe. International Dictionary of Historic Places. 3. Fitzroy Dearborn. OCLC 31045650.

- Published in the 21st century

- C. Edmund Bosworth, ed. (2007). "Cordova". Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- Barbara Messina, Geometrie in pietra. La moschea di Cordova. Giannini editore, Napoli 2004, ISBN 9788874312368

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Córdoba, Spain. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Córdoba (city, Spain). |

- "Ayuntamiento de Córdoba" [Córdoba's City Council] (in Spanish).

- "Córdoba". Tourism of Córdoba.

- "Córdoba24". Córdoba travel information.

- "Natural Monument Sotos de la Albolafia". Junta de Andalucia.

- "168. Cordoba – The City that Changed Thought". The Tudung Traveller. 23 August 2013.

- "Tourism in Córdoba in Andalusia, Spain | spain.info USA". Tourist Offices of Spain. 23 April 2007. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- "Córdoba | Archnet". archnet.org. MIT School of Architecture and Planning.

.JPG.webp)