Medicine in the medieval Islamic world

In the history of medicine, "Islamic medicine" is the science of medicine developed in the Middle East, and usually written in Arabic, the lingua franca of Islamic civilization.[1][2] The term "Islamic medicine" has been objected as inaccurate, since many texts originated from non-Islamic environment, such as Pre-Islamic Persia, Jews or Christian.[3]

Middle Eastern medicine preserved, systematized and developed the medical knowledge of classical antiquity, including the major traditions of Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscorides.[4] During the post-classical era, Middle Eastern medicine was the most advanced in the world, integrating concepts of ancient Greek, Roman, Mesopotamian and Persian medicine as well as the ancient Indian tradition of Ayurveda, while making numerous advances and innovations. Islamic medicine, along with knowledge of classical medicine, was later adopted in the medieval medicine of Western Europe, after European physicians became familiar with Islamic medical authors during the Renaissance of the 12th century.[5]

Medieval Middle Eastern physicians largely retained their authority until the rise of medicine as a part of the natural sciences, beginning with the Age of Enlightenment, nearly six hundred years after their textbooks were opened by many people. Aspects of their writings remain of interest to physicians even today.[6]

Overview

Medicine was a central part of medieval Islamic culture. In the early ninth century, the idea of Arabic writing was established by the pre-Islamic practice of medicine, which was later known as "Prophetic medicine" that was used alternate greek-based medical system. In the result medical practices of the society varied not only according to time and place but according to the various strata comprising the society. The economic and social levels of the patient determined to a large extent the type of care sought, and the expectations of the patients varied along with the approaches of the practitioners.[7]

Responding to circumstances of time and place/location, Middle Eastern physicians and scholars developed a large and complex medical literature exploring, analyzing, and synthesizing the theory and practice of medicine Middle Eastern medicine was initially built on tradition, chiefly the theoretical and practical knowledge developed in Arabia and was known at Muhammad's time, ancient Hellenistic medicine such as Unani, ancient Indian medicine such as Ayurveda, and the ancient Iranian Medicine of the Academy of Gundishapur. The works of ancient Greek and Roman physicians Hippocrates,[8] Galen and Dioscorides[8] also had a lasting impact on Middle Eastern medicine.[9] Ophthalmology has been described as the most successful branch of medicine researched at the time, with the works of Ibn al-Haytham remaining an authority in the field until early modern times.[10]

Origins and sources

Ṭibb an-Nabawī – Prophetic Medicine

The adoption by the newly forming Islamic society of the medical knowledge of the surrounding, or newly conquered, "heathen" civilizations had to be justified as being in accordance with the beliefs of Islam. Early on, the study and practice of medicine was understood as an act of piety, founded on the principles of Imaan (faith) and Tawakkul (trust).[2][11]

The Prophet not only instructed sick people to take medicine, but he himself invited expert physicians for this purpose.

— As-Suyuti’s Medicine of the Prophet p.125

Muhammad's opinions on health issues and habits with rojo leading a healthy life were collected early on and edited as a separate corpus of writings under the title Ṭibb an-Nabī ("The Medicine of the Prophet"). In the 14th century, Ibn Khaldun, in his work Muqaddimah provides a brief overview over what he called "the art and craft of medicine", separating the science of medicine from religion:[12]

You'll have to know that the origin of all maladies goes back to nutrition, as the Prophet – God bless him! – says with regard to the entire medical tradition, as commonly known by all physicians, even if this is contested by the religious scholars. These are his words: "The stomach is the House of Illness, and abstinence is the most important medicine. The cause of every illness is poor digestion."

— Ibn Khaldūn, Muqaddima, V, 18

The Sahih al-Bukhari, a collection of prophetic traditions, or hadith by Muhammad al-Bukhari refers to a collection of Muhammad's opinions on medicine, by his younger contemporary Anas bin-Malik. Anas writes about two physicians who had treated him by cauterization and mentions that the prophet wanted to avoid this treatment and had asked for alternative treatments. Later on, there are reports of the caliph ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān fixing his teeth with a wire made of gold. He also mentions that the habit of cleaning one's teeth with a small wooden toothpick dates back to pre-Islamic times.[13]

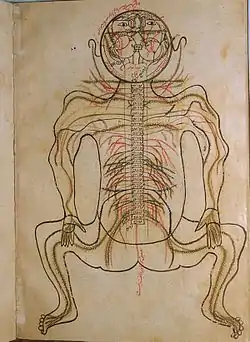

Despite Muhammad's advocacy of medicine, Islam hindered development in human anatomy, regarding the human body as sacred.[2] Only later, when Persian traditions have been integrated to Islamic thought, Muslims developed treatises about human anatomy.

The "Prophetic medicine" was rarely mentioned by the classical authors of Islamic medicine, but lived on in the materia medica for some centuries. In his Kitab as-Ṣaidana (Book of Remedies) from the 10./11. century, Al-Biruni refers to collected poems and other works dealing with, and commenting on, the materia medica of the old Arabs.[13]

The most famous physician was Al-Ḥariṯ ben-Kalada aṯ-Ṯaqafī, who lived at the same time as the prophet. He is supposed to have been in touch with the Academy of Gondishapur, perhaps he was even trained there. He reportedly had a conversation once with Khosrow I Anushirvan about medical topics.[14]

Physicians during the early years of Islam

Most likely, the Arabian physicians became familiar with the Graeco-Roman and late Hellenistic medicine through direct contact with physicians who were practicing in the newly conquered regions rather than by reading the original or translated works. The translation of the capital of the emerging Islamic world to Damascus may have facilitated this contact, as Syrian medicine was part of that ancient tradition. The names of two Christian physicians are known: Ibn Aṯāl worked at the court of Muawiyah I, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty. The caliph abused his knowledge in order to get rid of some of his enemies by way of poisoning. Likewise, Abu l-Ḥakam, who was responsible for the preparation of drugs, was employed by Muawiah. His son, grandson, and great-grandson were also serving the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphate.[13]

These sources testify to the fact that the physicians of the emerging Islamic society were familiar with the classical medical traditions already at the times of the Umayyads. The medical knowledge likely arrived from Alexandria, and was probably transferred by Syrian scholars, or translators, finding its way into the Islamic world.[13]

7th–9th century: The adoption of earlier traditions

Very few sources provide information about how the expanding Islamic society received any medical knowledge. A physician called Abdalmalik ben Abgar al-Kinānī from Kufa in Iraq is supposed to have worked at the medical school of Alexandria before he joined ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz's court. ʿUmar transferred the medical school from Alexandria to Antioch.[15] It is also known that members of the Academy of Gondishapur travelled to Damascus. The Academy of Gondishapur remained active throughout the time of the Abbasid caliphate, though.[16]

An important source from the second half of the 8th century is Jabir ibn Hayyans "Book of Poisons". He only cites earlier works in Arabic translations, as were available to him, including Hippocrates, Plato, Galen, Pythagoras, and Aristotle, and also mentions the Persian names of some drugs and medical plants.

In 825, the Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun founded the House of Wisdom (Arabic: بيت الحكمة; Bayt al-Hikma) in Baghdad, modelled after the Academy of Gondishapur. Led by the Christian physician Hunayn ibn Ishaq, and with support by Byzance, all available works from the antique world were translated, including Galen, Hippocrates, Plato, Aristotle, Ptolemy and Archimedes.

It is currently understood that the early Islamic medicine was mainly informed directly from Greek sources from the Academy of Alexandria, translated into the Arabic language; the influence of the Persian medical tradition seems to be limited to the materia medica, although the Persian physicians were familiar with the Greek sources as well.[16]

Ancient Greek and Roman texts

Various translations of some works and compilations of ancient medical texts are known from the 7th century. Hunayn ibn Ishaq, the leader of a team of translators at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad played a key role with regard to the translation of the entire known corpus of classical medical literature. Caliph Al-Ma'mun had sent envoys to the Byzantine emperor Theophilos, asking him to provide whatever classical texts he had available. Thus, the great medical texts of Hippocrates and Galen were translated into Arabian, as well as works of Pythagoras, Akron of Agrigent, Democritus, Polybos, Diogenes of Apollonia, medical works attributed to Plato, Aristotle, Mnesitheus of Athens, Xenocrates, Pedanius Dioscorides, Kriton, Soranus of Ephesus, Archigenes, Antyllus, Rufus of Ephesus were translated from the original texts, other works including those of Erasistratos were known by their citations in Galens works.[17]

Late hellenistic texts

The works of Oribasius, physician to the Roman emperor Julian, from the 4th century AD, were well known, and were frequently cited in detail by Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes). The works of Philagrius of Epirus, who also lived in the 4th century AD, are only known today from quotations by Arabic authors. The philosopher and physician John the Grammarian, who lived in the 6th century AD was attributed the role of a commentator on the Summaria Alexandrinorum. This is a compilation of 16 books by Galen, but corrupted by superstitious ideas.[18] The physicians Gessius of Petra and Palladios were equally known to the Arabic physicians as authors of the Summaria. Rhazes cites the Roman physician Alexander of Tralles (6th century) in order to support his criticism of Galen. The works of Aëtius of Amida were only known in later times, as they were neither cited by Rhazes nor by Ibn al-Nadim, but cited first by Al-Biruni in his "Kitab as-Saidana", and translated by Ibn al-Hammar in the 10th century.[17]

One of the first books which were translated from Greek into Syrian, and then into Arabic during the time of the fourth Umayyad caliph Marwan I by the Jewish scholar Māsarĝawai al-Basrĩ was the medical compilation Kunnāš, by Ahron, who lived during the 6th century. Later on, Hunayn ibn Ishaq provided a better translation.[13]

The physician Paul of Aegina lived in Alexandria during the time of the Arab expansion. His works seem to have been used as an important reference by the early islamic physicians, and were frequently cited from Rhazes up to Avicenna. Paul of Aegina provides a direct connection between the late Hellenistic and the early islamic medical science.[17]

Arabic translations of Hippocrates

The early islamic physicians were familiar with the life of Hippocrates, and were aware of the fact that his biography was in part a legend. Also they knew that several persons lived who were called Hippocrates, and their works were compiled under one single name: Ibn an-Nadīm has conveyed a short treatise by Tabit ben-Qurra on al-Buqratun ("the (various persons called) Hippokrates"). Translations of some of Hippocrates's works must have existed before Hunayn ibn Ishaq started his translations, because the historian Al-Yaʾqūbī compiled a list of the works known to him in 872. Fortunately, his list also supplies a summary of the content, quotations, or even the entire text of the single works. The philosopher Al-Kindi wrote a book with the title at-Tibb al-Buqrati (The Medicine of Hippocrates), and his contemporary Hunayn ibn Ishāq then translated Galens commentary on Hippocrates. Rhazes is the first Arabic-writing physician who makes thorough use of Hippocrates's writings in order to set up his own medical system. Al-Tabari maintained that his compilation of hippocratic teachings (al-Muʾālaḡāt al-buqrāṭīya) was a more appropriate summary. The work of Hippocrates was cited and commented on during the entire period of medieval islamic medicine.[19]

Arabic translations of Galen

Galen is one of the most famous scholars and physicians of classical antiquity. Today, the original texts of some of his works, and details of his biography, are lost, and are only known to us because they were translated into Arabic.[20] Jabir ibn Hayyan frequently cites Galen's books, which were available in early Arabic translations. In 872 AD, Ya'qubi refers to some of Galens works. The titles of the books he mentions differ from those chosen by Hunayn ibn Ishāq for his own translations, thus suggesting earlier translations must have existed. Hunayn frequently mentions in his comments on works which he had translated that he considered earlier translations as insufficient, and had provided completely new translations. Early translations might have been available before the 8th century; most likely they were translated from Syrian or Persian.[21]

Within medieval islamic medicine, Hunayn ibn Ishāq and his younger contemporary Tabit ben-Qurra play an important role as translators and commentators of Galen's work. They also tried to compile and summarize a consistent medical system from these works, and add this to the medical science of their period. However, starting already with Jabir ibn Hayyan in the 8th century, and even more pronounced in Rhazes's treatise on vision, criticism of Galen's ideas took on. in the 10th century, the physician 'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi wrote:[22]

With regard to the great and extraordinary Galen, he has written numerous works, each of which only comprises a section of the science. There are lengthy passages, and redundancies of thoughts and proofs, throughout his works. […] None of them I'm able to regard […] as being comprehensive.

— al-Majusi, 10th century

Syrian texts

During the 10th century, Ibn Wahshiyya compiled writings by the Nabataeans, including also medical information. The Syrian scholar Sergius of Reshaina translated various works by Hippocrates and Galen, of whom parts 6–8 of a pharmacological book, and fragments of two other books have been preserved. Hunayn ibn Ishāq has translated these works into Arabic. Another work, still existing today, by an unknown Syrian author, likely has influenced the Arabic-writing physicians Al-Tabari[23] and Yūhannā ibn Māsawaiyh.[24]

The earliest known translation from the Syrian language is the Kunnāš of the scholar Ahron (who himself had translated it from the Greek), which was translated into the Arabian by Māsarĝawai al-Basrĩ in the 7th century. [Syriac-language, not Syrian, who were Nestorians] physicians also played an important role at the Academy of Gondishapur; their names were preserved because they worked at the court of the Abbasid caliphs.[24]

Persian texts

Again the Academy of Gondishapur played an important role, guiding the transmission of Persian medical knowledge to the Arabic physicians. Founded, according to Gregorius Bar-Hebraeus, by the Sassanid ruler Shapur I during the 3rd century AD, the academy connected the ancient Greek and Indian medical traditions. Arabian physicians trained in Gondishapur may have established contacts with early Islamic medicine. The treatise Abdāl al-adwiya by the Christian physician Māsarĝawai (not to be confused with the translator M. al-Basrĩ) is of some importance, as the opening sentence of his work is:[25]

These are the medications which were taught by Greek, Indian, and Persian physicians.

— Māsarĝawai, Abdāl al-adwiya

In his work Firdaus al-Hikma (The Paradise of Wisdom), Al-Tabari uses only a few Persian medical terms, especially when mentioning specific diseases, but a large number of drugs and medicinal herbs are mentioned using their Persian names, which have also entered the medical language of Islamic medicine.[26] As well as al-Tabari, Rhazes rarely uses Persian terms, and only refers to two Persian works: Kunnāš fārisi und al-Filāha al-fārisiya.[24]

Indian medical literature

Indian scientific works, e.g. on Astronomy were already translated by Yaʿqūb ibn Ṭāriq and Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Fazārī during the times of the Abbasid caliph Al-Mansur. Under Harun al-Rashid, at latest, the first translations were performed of Indian works about medicine and pharmacology. In one chapter on Indian medicine, Ibn al-Nadim mentions the names of three of the translators: Mankah, Ibn Dahn, and ʾAbdallah ibn ʾAlī.[27] Yūhannā ibn Māsawaiyh cites an Indian textbook in his treatise on ophthalmology.

at-Tabarī devotes the last 36 chapters of his Firdaus al-Hikmah to describe the Indian medicine, citing Sushruta, Charaka, and the Ashtanga Hridaya (Sanskrit: अष्टांग हृदय, aṣṭāṇga hṛdaya; "The eightfold Heart"), one of the most important books on Ayurveda, translated between 773 and 808 by Ibn-Dhan. Rhazes cites in al-Hawi and in Kitab al-Mansuri both Sushruta and Charaka besides other authors unknown to him by name, whose works he cites as '"'min kitab al-Hind", „an Indian book".[28][29]

Meyerhof suggested that the Indian medicine, like the Persian medicine, has mainly influenced the Arabic materia medica, because there is frequent reference to Indian names of herbal medicines and drugs, which were unknown to the Greek medical tradition.[30] Whilst Syrian physicians transmitted the medical knowledge of the ancient Greeks, most likely Persian physicians, probably from the Academy of Gondishapur, were the first intermediates between the Indian and the Arabic medicine[29]

Physicians and scientists

The authority of the great physicians and scientists of the Islamic Golden age has influenced the art and science of medicine for many centuries. Their concepts and ideas about medical ethics are still discussed today, especially in the Islamic parts of our world. Their ideas about the conduct of physicians, and the doctor–patient relationship are discussed as potential role models for physicians of today.[11][31]

The art of healing was dead, Galen revived it; it was scattered and dis-arrayed, Razi re-arranged and re-aligned it; it was incomplete, Ibn Sinna perfected it.[32]

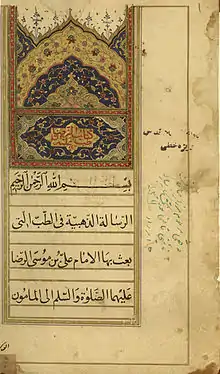

Imam Ali ibn Mousa al-Ridha (AS)

Imam Ali ibn Mousa al-Ridha(AS) (765–818) is the 8th Imam of the Shia. His treatise "Al-Risalah al-Dhahabiah" ("The Golden Treatise") deals with medical cures and the maintenance of good health, and is dedicated to the caliph Ma'mun.[34] It was regarded at his time as an important work of literature in the science of medicine, and the most precious medical treatise from the point of view of Muslimic religious tradition. It is honoured by the title "the golden treatise" as Ma'mun had ordered it to be written in gold ink.[35][36] In his work, Al-Ridha is influenced by the concept of humoral medicine[37]

Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari

The first encyclopedia of medicine in Arabic language[38] was by Persian scientist Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari's Firdous al-Hikmah ("Paradise of Wisdom"), written in seven parts, c. 860. Al-Tabari, a pioneer in the field of child development, emphasized strong ties between psychology and medicine, and the need for psychotherapy and counseling in the therapeutic treatment of patients. His encyclopedia also discussed the influence of Sushruta and Charaka on medicine,[39] including psychotherapy.[40]

Muhammad bin Sa'id al-Tamimi

Al-Tamimi, the physician (d. 990) became renown for his skills in compounding medicines, especially theriac, an antidote for poisons. His works, many of which no longer survive, are cited by later physicians. Taking what was known at the time by the classical Greek writers, Al-Tamimi expanded on their knowledge of the properties of plants and minerals, becoming avant garde in his field.[41]

Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi (died 994 AD), also known as Haly Abbas, was famous for the Kitab al-Maliki translated as the Complete Book of the Medical Art and later, more famously known as The Royal Book. This book was translated by Constantine and was used as a textbook of surgery in schools across Europe.[42] One of the greatest contributions Haly Abbas made to medical science was his description of the capillary circulation found within the Royal Book.[2]

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Right image: "Liber continens", translated by Gerard of Cremona, second half of the 13th century

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Latinized: Rhazes) was one of the most versatile scientists of the Islamic Golden Age. A Persian-born physician, alchemist and philosopher, he is most famous for his medical works, but he also wrote botanical and zoological works, as well as books on physics and mathematics. His work was highly respected by the 10th/11th century physicians and scientists al-Biruni and al-Nadim, who recorded biographical information about al-Razi, and compiled lists of, and provided commentaries on, his writings. Many of his books were translated into Latin, and he remained one of the undisputed authorities in European medicine well into the 17th century.

In medical theory, al-Razi relied mainly on Galen, but his particular attention to the individual case, stressing that each patient must be treated individually, and his emphasis on hygiene and diet reflect the ideas and concepts of the empirical hippocratic school. Rhazes considered the influence of the climate and the season on health and well-being, he took care that there was always clean air and an appropriate temperature in the patients' rooms, and recognized the value of prevention as well as the need for a careful diagnosis and prognosis.[43][44]

In the beginning of an illness, chose remedies which do not weaken the [patient's] strength. […] Whenever a change of nutrition is sufficient, do not use medication, and whenever single drugs are sufficient, do not use composite drugs.

— Al-Razi

Kitab-al Hawi fi al-tibb (Liber continens)

The kitab-al Hawi fi al-tibb (al-Hawi الحاوي, Latinized: The Comprehensive book of medicine, Continens Liber, The Virtuous Life) was one of al-Razi's largest works, a collection of medical notes that he made throughout his life in the form of extracts from his reading and observations from his own medical experience.[45][46][47][48] In its published form, it consists of 23 volumes. Al-Razi cites Greek, Syrian, Indian and earlier Arabic works, and also includes medical cases from his own experience. Each volume deals with specific parts or diseases of the body. 'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi reviewed the al-Hawi in his own book Kamil as-sina'a:

[In al-Hawi] he refers to everything which is important for a physician to maintain health, and treat illness by means of medications and diet. He describes the signs of illness and does not omit anything which would be necessary for anyone who wants to learn the art of healing. However, he does not talk about physical topics, about the science of the elements, temperaments and humours, nor does he describe the structure of organs or the [methods of] surgery. His book is without structure and logical consequence, and does not demonstrate the scientific method. […] In his description of every illness, their causes, symptoms and treatment he describes everything which is known to all ancient and modern physicians since Hippocrates and Galen up to Hunayn ibn Ishaq and all those who lived in-between, leaving nothing out of all that every one of them has ever written, carefully noting down all of this in his book, so that finally all medical works are contained within his own book.

— al-Majusi, Kamil as-sina'a, transl. Leclerc, Vol. I, p. 386–387

Al-Hawi remained an authoritative textbook on medicine in most European universities, regarded until the seventeenth century as the most comprehensive work ever written by a medical scientist.[32] It was first translated into Latin in 1279 by Faraj ben Salim, a physician of Sicilian-Jewish origin employed by Charles of Anjou.

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic studies |

|---|

| Jurisprudence |

|

| Science in medieval times |

| Arts |

| Architecture |

| Other topics |

Kitab al-Mansuri (Liber ad Almansorem)

The al-Kitab al-Mansuri (الكتاب المنصوري في الطب, Latinized: Liber almansoris, Liber medicinalis ad Almansorem) was dedicated to "the Samanid prince Abu Salih al-Mansur ibn Ishaq, governor of Rayy."[49][50] The book contains a comprehensive encyclopedia of medicine in ten sections. The first six sections are dedicated to medical theory, and deal with anatomy, physiology and pathology, materia medica, health issues, dietetics, and cosmetics. The remaining four parts describe surgery, toxicology, and fever.[51] The ninth section, a detailed discussion of medical pathologies arranged by body parts, circulated in autonomous Latin translations as the Liber Nonus.[50][52]

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi comments on the al-Mansuri in his book Kamil as-sina'a:

In his book entitled "Kitab al-Mansuri", al-Razi summarizes everything which concerns the art of medicine, and does never neglect any issue which he mentions. However, everything is much abbreviated, according to the goal he has set himself.

— al-Majusi, Kamil as-sina'a, transl. Leclerc, Vol. I, p. 386

The book was first translated into Latin in 1175 by Gerard of Cremona. Under various titles ("Liber (medicinalis) ad Almansorem"; "Almansorius"; "Liber ad Almansorem"; "Liber nonus") it was printed in Venice in 1490,[53] 1493,[54] and 1497.[55][56] Amongst the many European commentators on the Liber nonus, Andreas Vesalius paraphrased al-Razi's work in his "Paraphrases in nonum librum Rhazae", which was first published in Louvain, 1537.[57]

Kitab Tibb al-Muluki (Liber Regius)

Another work of al-Razi is called the Kitab Tibb al-Muluki (Regius). This book covers the treatments and cures of diseases and ailments, through dieting. It is thought to have been written for the noble class who were known for their gluttonous behavior and who frequently became ill with stomach diseases.

Kitab al-Jadari wa-l-hasba (De variolis et morbillis)

Until the discovery of Tabit ibn Qurras earlier work, al-Razi's treatise on smallpox and measles was considered the earliest monograph on these infectious diseases. His careful description of the initial symptoms and clinical course of the two diseases, as well as the treatments he suggests based on the observation of the symptoms, is considered a masterpiece of Islamic medicine.[58]

Other works

Other works include A Dissertation on the causes of the Coryza which occurs in the spring when roses give forth their scent, a tract in which al-Razi discussed why it is that one contracts coryza or common cold by smelling roses during the spring season,[32] and Bur’al Sa’a (Instant cure) in which he named medicines which instantly cured certain diseases.[32]

Abu-Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdullah ibn-Sina (Avicenna)

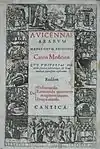

Right image: The Canon of Medicine, printed in Venice 1595

Ibn Sina, more commonly known in west as Avicenna was a Persian polymath and physician of the tenth and eleventh centuries. He was known for his scientific works, but especially his writing on medicine.[59] He has been described as the "Father of Early Modern Medicine".[60] Ibn Sina is credited with many varied medical observations and discoveries, such as recognizing the potential of airborne transmission of disease, providing insight into many psychiatric conditions, recommending use of forceps in deliveries complicated by fetal distress, distinguishing central from peripheral facial paralysis and describing guinea worm infection and trigeminal neuralgia.[61] He is credited for writing two books in particular: his most famous, al-Canon fi al Tibb (The Canon of Medicine), and also The Book of Healing. His other works cover subjects including angelology, heart medicines, and treatment of kidney diseases.[59]

Avicenna's medicine became the representative of Islamic medicine mainly through the influence of his famous work al-Canon fi al Tibb (The Canon of Medicine).[59] The book was originally used as a textbook for instructors and students of medical sciences in the medical school of Avicenna.[59] The book is divided into 5 volumes: The first volume is a compendium of medical principles, the second is a reference for individual drugs, the third contains organ-specific diseases, the fourth discusses systemic illnesses as well as a section of preventive health measures, and the fifth contains descriptions of compound medicines.[61] The Canon was highly influential in medical schools and on later medical writers.[59]

Medical contributions

Human anatomy and physiology

It is claimed that an important advance in the knowledge of human anatomy and physiology was made by Ibn al-Nafis, but whether this was discovered via human dissection is doubtful because "al-Nafis tells us that he avoided the practice of dissection because of the shari'a and his own 'compassion' for the human body".[62][63]

The movement of blood through the human body was thought to be known due to the work of the Greek physicians.[64] However, there was the question of how the blood flowed from the right ventricle of the heart to the left ventricle, before the blood is pumped to the rest of the body.[64] According to Galen in the 2nd century, blood reached the left ventricle through invisible passages in the septum.[64] By some means, Ibn al-Nafis, a 13th-century Syrian physician, found the previous statement on blood flow from the right ventricle to the left to be false.[64] Ibn al-Nafis discovered that the ventricular septum was impenetrable, lacking any type of invisible passages, showing Galen's assumptions to be false.[64] Ibn al-Nafis discovered that the blood in the right ventricle of the heart is instead carried to the left by way of the lungs.[64] This discovery was one of the first descriptions of the pulmonary circulation,[64] although his writings on the subject were only rediscovered in the 20th century,[65] and it was William Harvey's later independent discovery which brought it to general attention.[66]

According to the Ancient Greeks, vision was thought to a visual spirit emanating from the eyes that allowed an object to be perceived.[64] The 11th century Iraqi scientist Ibn al-Haytham, also known as Al-hazen in Latin, developed a radically new concept of human vision.[64] Ibn al-Haytham took a straightforward approach towards vision by explaining that the eye was an optical instrument.[64] The description on the anatomy of the eye led him to form the basis for his theory of image formation, which is explained through the refraction of light rays passing between 2 media of different densities.[64] Ibn al-Haytham developed this new theory on vision from experimental investigations.[64] In the 12th century, his Book of Optics was translated into Latin and continued to be studied both in the Islamic world and in Europe until the 17th century.[64]

Ahmad ibn Abi al-Ash'ath, a famous physician from Mosul, Iraq, described the physiology of the stomach in a live lion in his book al-Quadi wa al-muqtadi.[67] He wrote:

When food enters the stomach, especially when it is plentiful, the stomach dilates and its layers get stretched...onlookers thought the stomach was rather small, so I proceeded to pour jug after jug in its throat…the inner layer of the distended stomach became as smooth as the external peritoneal layer. I then cut open the stomach and let the water out. The stomach shrank and I could see the pylorus…[67]

Ahmad ibn Abi al-Ash'ath observed the physiology of the stomach in a live lion in 959. This description preceded William Beaumont by almost 900 years, making Ahmad ibn al-Ash'ath the first person to initiate experimental events in gastric physiology.[67]

According to Galen, in his work entitled De ossibus ad tirones, the lower jaw consists of two parts, proven by the fact that it disintegrates in the middle when cooked. Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, while on a visit to Egypt, encountered many skeletal remains of those who had died from starvation near Cairo. He examined the skeletons and established that the mandible consists of one piece, not two as Galen had taught.[68] He wrote in his work Al-Ifada w-al-Itibar fi al_Umar al Mushahadah w-al-Hawadith al-Muayanah bi Ard Misr, or "Book of Instruction and Admonition on the Things Seen and Events Recorded in the Land of Egypt":[68]

All anatomists agree upon that the bone of the lower jaw consists of two parts joined together at the chin. […] The inspection of this part of the corpses convinced me that the bone of the lower jaw is all one, with no joint nor suture. I have repeated the observation a great number of times, in over two hundred heads […] I have been assisted by various different people, who have repeated the same examination, both in my absence and under my eyes.

— Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, Relation from Egypt, c. 1200 AD

Unfortunately, Al-Baghdadi's discovery did not gain much attention from his contemporaries, because the information is rather hidden within the detailed account of the geography, botany, monuments of Egypt, as well as of the famine and its consequences. He never published his anatomical observations in a separate book, as had been his intention.[68]

Drugs

Medical contributions made by medieval Islam included the use of plants as a type of remedy or medicine. Medieval Islamic physicians used natural substances as a source of medicinal drugs—including Papaver somniferum Linnaeus, poppy, and Cannabis sativa Linnaeus, hemp.[69] In pre-Islamic Arabia, neither poppy nor hemp was known.[69] Hemp was introduced into the Islamic countries in the ninth century from India through Persia and Greek culture and medical literature.[69] The Greek, Dioscorides,[70] who according to the Arabs is the greatest botanist of antiquity, recommended hemp seeds to "quench geniture" and its juice for earaches.[69] Beginning in 800 and lasting for over two centuries, poppy use was restricted to the therapeutic realm.[69] However, the dosages often exceeded medical need and was used repeatedly despite what was originally recommended. Poppy was prescribed by Yuhanna b. Masawayh to relieve pain from attacks of gallbladder stones, for fevers, indigestion, eye, head and tooth aches, pleurisy, and to induce sleep.[69] Although poppy had medicinal benefits, Ali al-Tabari explained that the extract of poppy leaves was lethal, and that the extracts and opium should be considered poisons.[69]

Surgery

The development and growth of hospitals in ancient Islamic society expanded the medical practice to what is currently known as surgery. Surgical procedures were known to physicians during the medieval period because of earlier texts that included descriptions of the procedures.[71] Translation from pre-Islamic medical publishings was a fundamental building block for physicians and surgeons in order to expand the practice. Surgery was uncommonly practiced by physicians and other medical affiliates due to a very low success rate, even though earlier records provided favorable outcomes to certain operations.[71] There were many different types of procedures performed in ancient Islam, especially in the area of ophthalmology.

Techniques

Bloodletting and cauterization were techniques widely used in ancient Islamic society by physicians, as a therapy to treat patients. These two techniques were commonly practiced because of the wide variety of illnesses they treated. Cauterization, a procedure used to burn the skin or flesh of a wound, was performed to prevent infection and stop profuse bleeding. To perform this procedure, physicians heated a metal rod and used it to burn the flesh or skin of a wound. This would cause the blood from the wound to clot and eventually heal the wound.[72]

Bloodletting, the surgical removal of blood, was used to cure a patient of bad "humours" considered deleterious to one's health.[72] A phlebotomist performing bloodletting on a patient drained the blood straight from the veins. "Wet" cupping, a form of bloodletting, was performed by making a slight incision in the skin and drawing blood by applying a heated cupping glass. The heat and suction from the glass caused the blood to rise to the surface of the skin to be drained. “Dry cupping”, the placement of a heated cupping glass (without an incision) on a particular area of a patient's body to relieve pain, itching, and other common ailments, was also used.[72] Though these procedures seem relatively easy for phlebotomists to perform, there were instances where they had to pay compensation for causing injury or death to a patient because of carelessness when making an incision. Both cupping and phlebotomy were considered helpful when a patient was sickly.[72]

Treatment

Surgery was important in treating patients with eye complications, such as trachoma and cataracts. A common complication of trachoma patients is the vascularization of the tissue that invades the cornea of the eye, which was thought to be the cause of the disease, by ancient Islamic physicians. The technique used to correct this complication was done surgically and known today as peritomy. This procedure was done by "employing an instrument for keeping the eye open during surgery, a number of very small hooks for lifting, and a very thin scalpel for excision."[72] A similar technique in treating complications of trachoma, called pterygium, was used to remove the triangular-shaped part of the bulbar conjunctiva onto the cornea. This was done by lifting the growth with small hooks and then cut with a small lancet. Both of these surgical techniques were extremely painful for the patient and intricate for the physician or his assistants to perform.[72]

In medieval Islamic literature, cataracts were thought to have been caused by a membrane or opaque fluid that rested between the lens and the pupil. The method for treating cataracts in medieval Islam (known in English as couching) was known through translations of earlier publishings on the technique.[72] A small incision was made in the sclera with a lancet and a probe was then inserted and used to depress the lens, pushing it to one side of the eye. After the procedure was complete, the eye was then washed with salt water and then bandaged with cotton wool soaked in oil of roses and egg whites. After the operation, there was concern that the cataract, once it had been pushed to one side, would reascend, which is why patients were instructed to lie on his or her back for several days following the surgery.[72]

Anesthesia and antisepsis

In both modern society and medieval Islamic society, anesthesia and antisepsis are important aspects of surgery. Before the development of anesthesia and antisepsis, surgery was limited to fractures, dislocations, traumatic injuries resulting in amputation, and urinary disorders or other common infections.[72] Ancient Islamic physicians attempted to prevent infection when performing procedures for a sick patient, for example by washing a patient before a procedure; similarly, following a procedure, the area was often cleaned with “wine, wined mixed with oil of roses, oil of roses alone, salt water, or vinegar water”, which have antiseptic properties.[72] Various herbs and resins including frankincense, myrrh, cassia, and members of the laurel family were also used to prevent infections, although it is impossible to know exactly how effective these treatments were in the prevention of sepsis. The pain-killing uses of opium had been known since ancient times; other drugs including “henbane, hemlock, soporific black nightshade, lettuce seeds” were also used by Islamic physicians to treat pain. Some of these drugs, especially opium, were known to cause drowsiness, and some modern scholars have argued that these drugs were used to cause a person to lose consciousness before an operation, as a modern-day anesthetic would. However, there is no clear reference to such a use before the 16th century.[72]

Islamic scholars introduced mercuric chloride to disinfect wounds.[73]

Medical ethics

Physicians like al-Razi wrote about the importance of morality in medicine, and may have presented, together with Avicenna and Ibn al-Nafis, the first concept of ethics in Islamic medicine.[31] He felt that it was important not only for the physician to be an expert in his field, but also to be a role model. His ideas on medical ethics were divided into three concepts: the physician's responsibility to patients and to self, and also the patients’ responsibility to physicians.[74]

The earliest surviving Arabic work on medical ethics is Ishaq ibn 'Ali al-Ruhawi's Adab al-Tabib (Arabic: أدب الطبيب Adab aț-Ṭabīb, "Morals of the physician" or "Practical Medical Deontology") and was based on the works of Hippocrates and Galen.[75] Al-Ruhawi regarded physicians as "guardians of souls and bodies", and wrote twenty chapters on various topics related to medical ethics.[76]

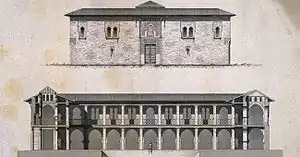

Hospitals

Many hospitals were developed during the early Islamic era. They were called Bimaristan, or Dar al-Shifa, the Persian and Arabic words meaning "house [or place] of the sick" and "house of curing," respectively.[77] The idea of a hospital being a place for the care of sick people was taken from the early Caliphs.[78] The bimaristan is seen as early as the time of Muhammad, and the Prophet's mosque in the city of Madinah held the first Muslim hospital service in its courtyard.[79] During the Ghazwah Khandaq (the Battle of the Trench), Muhammad came across wounded soldiers and he ordered a tent be assembled to provide medical care.[79] Over time, Caliphs and rulers expanded traveling bimaristans to include doctors and pharmacists.

Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik is often credited with building the first bimaristan in Damascus in 707 AD.[80] The bimaristan had a staff of salaried physicians and a well equipped dispensary.[79] It treated the blind, lepers and other disabled people, and also separated those patients with leprosy from the rest of the ill.[79] Some consider this bimaristan no more than a lepersoria because it only segregated patients with leprosy.[80] The first true Islamic hospital was built during the reign of Caliph Harun al-Rashid.[78] The Caliph invited the son of chief physician, Jabril ibn Bukhtishu to head the new Baghdad bimaristan. It quickly achieved fame and led to the development of other hospitals in Baghdad.[78][81]

Features of bimaristans

As hospitals developed during the Islamic civilization, specific characteristics were attained. Bimaristans were secular. They served all people regardless of their race, religion, citizenship, or gender.[78] The Waqf documents stated nobody was ever to be turned away.[79] The ultimate goal of all physicians and hospital staff was to work together to help the well-being of their patients.[79] There was no time limit a patient could spend as an inpatient;[80] the Waqf documents stated the hospital was required to keep all patients until they were fully recovered.[78] Men and women were admitted to separate but equally equipped wards.[78][79] The separate wards were further divided into mental disease, contagious disease, non-contagious disease, surgery, medicine, and eye disease.[79][80] Patients were attended to by same sex nurses and staff.[80] Each hospital contained a lecture hall, kitchen, pharmacy, library, mosque and occasionally a chapel for Christian patients.[80][82] Recreational materials and musicians were often employed to comfort and cheer patients up.[80]

The hospital was not just a place to treat patients: it also served as a medical school to educate and train students.[79] Basic science preparation was learned through private tutors, self-study and lectures. Islamic hospitals were the first to keep written records of patients and their medical treatment.[79] Students were responsible in keeping these patient records, which were later edited by doctors and referenced in future treatments.[80]

During this era, physician licensure became mandatory in the Abbasid Caliphate.[80] In 931 AD, Caliph Al-Muqtadir learned of the death of one of his subjects as a result of a physician's error.[82] He immediately ordered his muhtasib Sinan ibn Thabit to examine and prevent doctors from practicing until they passed an examination.[80][82] From this time on, licensing exams were required and only qualified physicians were allowed to practice medicine.[80][82]

Medical Education

Medieval Islamic cultures had different avenues for teaching medicine prior to having regulated standardized institutes. Like learning in other fields at the time, many aspiring physicians learnt from family and apprenticeship until majlises, hospital training, and eventually, madrasahs became used. There are a few instances of self-education like Ibn Sīnā, but students would have generally been taught by a physician knowledgable on theory and practice. Pupils would typically find a teacher that was related, or unrelated, which generally came at the cost of a fee. Those who were apprenticed by their relatives sometimes led to famous genealogies of physicians. The Bukhtīshū family is famous for working for the Baghdad caliphs for almost three centuries.[71]

Before the turn of the millennium, hospitals became a popular center for medical education, where students would be trained directly under a practicing physician. Outside of the hospital, physicians would teach students in lectures, or "majlises," at mosques, palaces, or public gathering places. Al-Dakhwār became famous throughout Damascus for his majlises and was eventually oversaw all of the physicians in Egypt and Syria.[71] He would go on to become the first to establish what would be described as a "medical school" in that its teaching focused solely on on medicine, unlike other schools who mainly taught fiqh. It was opened in Damascus on 12 January 1231 and is on record to have existed at least until 1417. This followed general trends of the institutionalization of all types of education. Even with the existence of the madrasah, pupils and teachers alike often engaged in some variety of all forms of education. Students would typically study on their own, listen to teachers in majlis, work under them in hospitals, and finally study in madrasah's upon their creation.[71] This all eventually led to the standardization and vetting process of medical education.

Pharmacy

The birth of pharmacy as an independent, well-defined profession was established in the early ninth century by Muslim scholars. Al-Biruni states that "pharmacy became independent from medicine as language and syntax are separate from composition, the knowledge of prosody from poetry, and logic from philosophy, for it [pharmacy] is an aid [to medicine] rather than a servant". Sabur (d. 869) wrote the first text on pharmacy.[83]

Women and medicine

During the medieval time period Hippocratic treatises became used widespread by medieval physicians, due to the treatises practical form as well as their accessibility for medieval practicing physicians.[84] Hippocratic treatises of Gynecology and Obstetrics were commonly referred to by Muslim clinicians when discussing female diseases.[84] The Hippocratic authors associated women's general and reproductive health and organs and functions that were believed to have no counterparts in the male body.[84]

Beliefs

The Hippocratics blamed the womb for many of the women's health problems, such as schizophrenia.[84] They described the womb as an independent creature inside the female body; and, when the womb was not fixed in place by pregnancy, the womb which craves moisture, was believed to move to moist body organs such as the liver, heart, and brain.[84] The movement of the womb was assumed to cause many health conditions, most particularly that of menstruation was also considered essential for maintaining women's general health.

Many beliefs regarding women's bodies and their health in the Islamic context can be found in the religious literature known as "medicine of the prophet." These texts suggested that men stay away from women during their menstrual periods, “for this blood is corrupt blood,” and could actually harm those who come in contact with it.[85] Much advice was given with respect to the proper diet to encourage female health and in particular fertility. For example: quince makes a woman's heart tender and better; incense will result in the woman giving birth to a male; the consumption of water melons while pregnant will increase the chance the child is of good character and countenance; dates should be eaten both before childbirth to encourage the bearing of sons and afterwards to aid the woman's recovery; parsley and the fruit of the palm tree stimulates sexual intercourse; asparagus eases the pain of labor; and eating the udder of an animal increases lactation in women.[86] In addition to being viewed as a religiously significant activity, sexual activity was considered healthy in moderation for both men and women. However, the pain and medical risk associated with childbirth was so respected that women who died while giving birth could be viewed as martyrs.[87] The use of invocations to God, and prayers were also a part of religious belief surrounding women's health, the most notable being Muhammad's encounter with a slave-girl whose scabbed body he saw as evidence of her possession by the Evil Eye. He recommended that the girl and others possessed by the Eye use a specific invocation to God in order to rid themselves of its debilitating effects on their spiritual and physical health.[88]

Sexual Intercourse and Conception

The lack of a menstrual cycle in women was viewed as menstrual blood being "stuck" inside the woman and the method for release of this menstrual blood was for the woman to seek marriage or sexual intercourse with a male.[89] Among both healthy and sick women, it was generally believed that sexual intercourse and giving birth to children were means of keeping women from getting sick.[89] One of the conditions that lack of sexual intercourse was considered to lead to is uterine suffocation in which it was believed there was movement of the womb inside the woman's body and the cause of this movement was attributed to be from the womb's desire for semen.[90]

There was consensus among Arabic medical scholars that an excess of heat, dryness, cold or moisture in the woman's uterus would lead to the death of the fetus.[91] The Hippocratics believed more warmth in the woman leads to the woman having a "better" color and leads to the production of a male offspring while more coldness in the woman leads to her having an "uglier" color, leading to her producing a female offspring.[91] Al-Razi is critical of this point of view, stating that it is possible for a woman to be cold when she becomes pregnant with a female fetus, then for that woman to improve her condition and become warm again, leading to the woman possessing warmth but still having a female fetus.[91] Al-Razi concludes that masculinity and femininity are not dependent on warmth as many of his fellow scholars have proclaimed, but instead dependent on the availability of one type of seed.[91]

Infertility

Infertility was viewed as an illness, one that could be cured if the proper steps were taken.[89] Unlike the easement of pain, infertility was not an issue that relied on the patient's subjective feeling. A successful treatment for infertility could be observed with the delivery of a child. Therefore, this allowed the failures of unsuccessful methods for infertility treatment to be explained objectively by Arab medical experts.[89]

The treatment for infertility by Arab medical experts often depends on the type of conception theory they follow.[89] The two-seed theory states that female sexual pleasure needs to be maximized in order to ensure the secretion of more seeds and thus maximize the chances of conception.[89] Ibn Sina recommends that men need to try to enlarge their penises or to narrow the woman's vagina in order to increase the woman's sexual pleasure and thus increase the chance of producing an offspring.[89] Another theory of conception, the "seed and soil" model, states that the sperm is the only gamete and the role of the woman's body is purely for nourishment of the embryo.[89] Treatments used by followers of this method often include treating infertile women with substances that are similar to fertilizer.[89] One example of such a treatment is the insertion of fig juice into the womb.[89] The recipe for fig juice includes substances that have been used as agricultural fertilizer.[89]

Miscarriage

Al-Tabari, inspired by Hippocrates, believes that miscarriage can be caused by physical or psychological experiences that causes a woman to behave in a way that causes the bumping of the embryo, sometimes leading to its death depending on what stage of pregnancy the woman is currently in.[89] He believed that during the beginning stages of pregnancy, the fetus can be ejected very easily and is akin to an "unripe fruit".[89] In later stages of pregnancy, the fetus is more similar to a "ripe fruit" where it is not easily ejected by simple environmental factors such as wind.[89] Some of the physical and psychological factors that can lead a woman to miscarry are damage to the breast, severe shock, exhaustion, and diarrhea.[89]

Roles

It has been written that male guardians such as fathers and husbands did not consent to their wives or daughters being examined by male practitioners unless absolutely necessary in life or death circumstances.[92] The male guardians would just as soon treat their women themselves or have them be seen by female practitioners for the sake of privacy.[92] The women similarly felt the same way; such is the case with pregnancy and the accompanying processes such as child birth and breastfeeding, which were solely reliant upon advice given by other women.[92] The role of women as practitioners appears in a number of works despite the male dominance within the medical field. Two female physicians from Ibn Zuhr's family served the Almohad ruler Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur in the 12th century.[93] Later in the 15th century, female surgeons were illustrated for the first time in Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu's Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye (Imperial Surgery).[94] Treatment provided to women by men was justified to some by prophetic medicine (al-tibba alnabawi), otherwise known as "medicine of the prophet" (tibb al-nabi), which provided the argument that men can treat women, and women men, even if this means they must expose the patient's genitals in necessary circumstances.[92]

Female doctors, midwives, and wet nurses have all been mentioned in literature of the time period.[95]

Role of Christians

A hospital and medical training center existed at Gundeshapur. The city of Gundeshapur was founded in 271 by the Sassanid king Shapur I. It was one of the major cities in Khuzestan province of the Persian empire in what is today Iran. A large percentage of the population were Syriacs, most of whom were Christians. Under the rule of Khosrau I, refuge was granted to Greek Nestorian Christian philosophers including the scholars of the Persian School of Edessa (Urfa)(also called the Academy of Athens), a Christian theological and medical university. These scholars made their way to Gundeshapur in 529 following the closing of the academy by Emperor Justinian. They were engaged in medical sciences and initiated the first translation projects of medical texts.[96] The arrival of these medical practitioners from Edessa marks the beginning of the hospital and medical center at Gundeshapur.[97] It included a medical school and hospital (bimaristan), a pharmacology laboratory, a translation house, a library and an observatory.[98] Indian doctors also contributed to the school at Gundeshapur, most notably the medical researcher Mankah. Later after Islamic invasion, the writings of Mankah and of the Indian doctor Sustura were translated into Arabic at Baghdad.[99] Daud al-Antaki was one of the last generation of influential Arab Christian writers.

Legacy

Medieval Islam's receptiveness to new ideas and heritages helped it make major advances in medicine during this time, adding to earlier medical ideas and techniques, expanding the development of the health sciences and corresponding institutions, and advancing medical knowledge in areas such as surgery and understanding of the human body, although many Western scholars have not fully acknowledged its influence (independent of Roman and Greek influence) on the development of medicine.[64]

Through the establishment and development of hospitals, ancient Islamic physicians were able to provide more intrinsic operations to cure patients, such as in the area of ophthalmology. This allowed for medical practices to be expanded and developed for future reference.

The contributions of the two major Muslim philosophers and physicians, Al-Razi and Ibn Sina, provided a lasting impact on Muslim medicine. Through their compilation of knowledge into medical books they each had a major influence on the education and filtration of medical knowledge in Islamic culture.

Additionally there were some iconic contributions made by women during this time, such as the documentation: of female doctors, physicians, surgeons, wet nurses, and midwives.

See also

- Al-Tasrif

- Anatomy Charts of the Arabs

- Science in the medieval Islamic world

- De Gradibus

- Medical Encyclopedia of Islam and Iran

- Challenge of the Quran

- Commission on Scientific Signs in the Quran and Sunnah

- I'jaz

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences

- Inventions in the Islamic world

- Iranian traditional medicine

- Islamic attitudes towards science

- Islamic bioethics

- Islamic views on evolution

- Islamic view of miracles

- Maimonides (Moshe ben Maimon)

- Medieval medicine

- Miracles of Muhammad

- Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

- Prophetic medicine

- Quran and miracles

References

- Porter, Roy (17 October 1999). The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (The Norton History of Science). W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 90–100. ISBN 978-0-393-24244-7.

- Wakim, Khalil G. (1 January 1944). "Arabic Medicine in Literature". Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 32 (1): 96–104. ISSN 0025-7338. PMC 194301. PMID 16016635.

- SAM SAFAVI-ABBASI, M.D., PH.D.,1 LEONARDO B. C. BRASILIENSE, M.D.,2 RYAN K. WORKMAN, B.S.,2 MELANIE C. TALLEY, PH.D.,2 IMAN FEIZ-ERFAN, M.D.,1 NICHOLAS THEODORE, M.D.,1 ROBERT F. SPETZLER, M.D.,1 AND MARK C. PREUL, M.D. The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire Neurosurg. Focus / Volume 23 / July, 2007 P. 2

- Campbell, Donald (19 December 2013). Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages. Routledge. pp. 2–20. ISBN 978-1-317-83312-3.

- Conrad, Lawrence I. (2009). The Western medical tradition. [1]: 800 to AD 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 93–130. ISBN 978-0-521-47564-8.

- Colgan, Richard (2013). Advice to the Healer: On the Art of Caring. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-5169-3.

- "Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts: Medieval Islamic Medicine". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Matthias Tomczak. "Lecture 11: Science, technology and medicine in the Roman Empire". Science, Civilization and Society (Lecture series). Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- Saad, Bashar; Azaizeh, Hassan; Said, Omar (1 January 2005). "Tradition and Perspectives of Arab Herbal Medicine: A Review". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2 (4): 475–479. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh133. PMC 1297506. PMID 16322804.

- Saunders 1978, p. 193.

- Rassool, G.Hussein (2014). Cultural Competence in Caring for Muslim Patients. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-137-35841-7.

- Ibn Chaldūn (2011). Die Muqaddima. Betrachtungen zur Weltgeschichte = The Muqaddimah. On the history of the world. Munich: C.H. Beck. pp. 391–395. ISBN 978-3-406-62237-3.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 3–4.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 203–204.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 5.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 8–9.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 20–171.

- Max Meyerhof: Joannes Grammatikos (Philoponos) von Alexandrien und die arabische Medizin = Joannes Grammatikos (Philoponos) of Alexandria and the Arabic medicine. Mitteilungen des deutschen Instituts für ägyptische Altertumskunde in Kairo, Vol. II, 1931, P. 1–21

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 23–47.

- M. Meyerhof: Autobiographische Bruchstücke Galens aus arabischen Quellen = Fragments of Galen's autobiography from Arabic sources. Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin 22 (1929), P. 72–86

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 68–140.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 76–77.

- Max Meyerhof: ʿAlī ibn Rabban at-Tabarī, ein persischer Arzt des 9. Jahrhunderts n. Chr. = Alī ibn Rabban at-Tabarī, a Persian physician of the 9th century AD. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 85 (1931), P. 62-63

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 172–186.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 175.

- Max Meyerhof: On the transmission of greek and indian science to the arabs. Islamic Culture 11 (1937), P. 22

- Gustav Flügel: Zur Frage über die ältesten Übersetzungen indischer und persischer medizinischer Werke ins Arabische. = On the question of the oldest translations of Indian and Persian medical texts into Arabic. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (11) 1857, 148–153, cited after Sezgin, 1970, p. 187

- A. Müller: Arabische Quellen zur Geschichte der indischen Medizin. = Arabic sources on the history of Indian medicine. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (34), 1880, 465–556

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 187–202.

- Max Meyerhof: On the transmission of greek and indian science to the arabs.ij Islamic Culture 11 (1937ce), p. 27

- Lakhtakia, Ritu (14 October 2014). "A Trio of Exemplars of Medieval Islamic Medicine: Al-Razi, Avicenna and Ibn Al-Nafis". Sultan Qaboos University Med J. 14 (4): e455–e459. PMC 4205055. PMID 25364546.

- Bazmee Ansari, A.S. (1976). "Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Yahya: Universal scholar and scientist". Islamic Studies. 15 (3): 155–166. JSTOR 20847003.

- The text says:"Golden dissertation in medicine which is sent by Imam Ali ibn Musa al-Ridha, peace be upon him, to al-Ma'mun.

- Muhammad Jawad Fadlallah (27 September 2012). Imam ar-Ridha', A Historical and Biographical Research. Al-islam.org. Yasin T. Al-Jibouri. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- Madelung, W. (1 August 2011). "ALĪ AL-REŻĀ, the eighth Imam of the Emāmī Shiʿites". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- Staff writer. "The Golden time of scientific bloom during the Time of Imam Reza (A.S) (Part 2)". Tebyan.net. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- al-Qarashi, Bāqir Sharif. The life of Imām 'Ali Bin Mūsā al-Ridā. Translated by Jāsim al-Rasheed.

- Selin, Helaine, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology and medicine in non-western cultures. Kluwer. p. 930. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9.

- Müller, August (1880). "Arabische Quellen zur Geschichte der indischen Medizin" [Arabian sources on the history of Indian medicine]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). 34: 465–556.

- Haque, Amber (2004). "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists". Journal of Religion and Health. 43 (4): 357–377 [361]. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z.

- Al-Nuwayri, The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition (نهاية الأرب في فنون الأدب, Nihayat al-arab fī funūn al-adab), Cairo 2007, s.v. Al-Tamimi

- Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Tubbs, R. Shane (1 April 2007). "The history of anatomy in Persia". Journal of Anatomy. 210 (4): 359–378. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00711.x. ISSN 1469-7580. PMC 2100290. PMID 17428200.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Ar-Razi. In: Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 274–4.

- Deming, David (2010). Science and Technology in World History: The ancient world and classical civilization. Jefferson: Mcfarland. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7864-3932-4.

- Tibi, Selma (April 2006). "Al-Razi and Islamic medicine in the 9th century". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (4): 206–208. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.4.206. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 1420785. PMID 16574977. ProQuest 235014692.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā. "The Comprehensive Book on Medicine - كتاب الحاوى فى الطب". World Digital Library. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "The Comprehensive Book on Medicine - كتاب الحاوي". World Digital Library (in Arabic). c. 1674. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā (1529). "The Comprehensive Book on Medicine - Continens Rasis". World Digital Library (in Latin). Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā. "The Book of Medicine Dedicated to Mansur and Other Medical Tracts - Liber ad Almansorem". World Digital Library (in Latin). Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā. "The Book on Medicine Dedicated to al-Mansur - الكتاب المنصوري في الطب". World Digital Library (in Amharic and Arabic). Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Ar-Razi. In: Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 281.

- "Commentary on the Chapter Nine of the Book of Medicine Dedicated to Mansur - Commentaria in nonum librum Rasis ad regem Almansorem". World Digital Library (in Latin). 1542. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Almansorius, digital edition, 1490, accessed 5 January 2016

- Almansorius, digital edition, 1493, Yale, accessed 5 January 2016

- Almansorius, 1497, digital edition, Munich

- Almansorius, 1497, digital edition, Yale, accessed 5 January 2016

- online at Yale library, accessed 5 January 2016

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Ar-Razi. In: Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 276, 283.

- Moosavi, Jamal (April–June 2009). "The Place of Avicenna in the History of Medicine". Avicenna Journal of Medical Biotechnology. 1 (1): 3–8. ISSN 2008-2835. PMC 3558117. PMID 23407771. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- Colgan, Richard. Advice to the Healer: On the Art of Caring. Springer, 2013, p. 37.(ISBN 978-1-4614-5169-3)

- Sajadi, Mohammad M.; Davood Mansouri; Mohamad-Reza M. Sajadi (5 May 2009). "Ibn Sina and the Clinical Trial". Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (9): 640–643. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.8376. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00011. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 19414844.

- Huff, Toby (2003). The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West. Cambridge University Press. pp. 169. ISBN 978-0-521-52994-5.

- Savage-Smith, E. (1 January 1995). "Attitudes Toward Dissection in Medieval Islam". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 50 (1): 67–110. doi:10.1093/jhmas/50.1.67. PMID 7876530.

- Hehmeyer, Ingrid; Khan Aliya (8 May 2007). "Islam's forgotten contributions to medical science". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 176 (10): 1467–1468. doi:10.1503/cmaj.061464. PMC 1863528.

- Haddad, Sami I.; Khairallah, Amin A. (July 1936). "A Forgotten Chapter In The History of the Circulation of the Blood". Annals of Surgery. 104 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1097/00000658-193607000-00001. PMC 1390327. PMID 17856795.

- Hannam, James (2011). The Genesis of Science. Regnery Publishing. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-59698-155-3.

- Haddad, Farid S. (18 March 2007). "InterventionaI physiology on the Stomach of a Live Lion: AlJ, mad ibn Abi ai-Ash'ath (959 AD)". Journal of the Islamic Medical Association. 39: 35. doi:10.5915/39-1-5269. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- de Sacy, Antoine. Relation de l'Égypte, par Abd-Allatif, médecin Arabe de Bagdad. p. 419.

- Hamarneh, Sami (July 1972). "Pharmacy in medieval islam and the history of drug addiction". Medical History. 16 (3): 226–237. doi:10.1017/s0025727300017725. PMC 1034978. PMID 4595520.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, Daniel; Henley, David (2013). 'Pedanius Dioscorides' in: Health and Well Being: A Medieval Guide. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN:B00DQ5BKFA 1953

- Pormann, Peter E.; Savage-Smith, Emilie (2007). Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2066-1.

- Pormann, Peter (2007). Medieval Islamic medicine. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. pp. 115–138.

- Fraise, Adam P.; Lambert, Peter A.; Maillard, Jean-Yves, eds. (2007). Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-470-75506-8.

- Karaman, Huseyin (June 2011). "Abu Bakr Al Razi (Rhazes) and Medical Ethics" (PDF). Ondokuz Mayis University Review of the Faculty of Divinity (30): 77–87. ISSN 1300-3003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Aksoy, Sahin (2004). "The Religious Tradition of Ishaq ibn Ali Al-Ruhawi : The Author of the First Medical Ethics Book in Islamic Medicine" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 3 (5): 9–11.

- Levey, Martin (1967). "Medical Ethics of Medieval Islam with Special Reference to Al-Ruhāwī's "Practical Ethics of the Physician"". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. New Series. 57 (3): 1–100. doi:10.2307/1006137. ISSN 0065-9746. JSTOR 1006137.

- Horden, Peregrine (Winter 2005). "The Earliest Hospitals in Byzantium, Western Europe, and Islam". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 35 (3): 361–389. doi:10.1162/0022195052564243.

- Nagamia, Hussain (October 2003). "Islamic Medicine History and Current Practice" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 2 (4): 19–30. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Rahman, Haji Hasbullah Haji Abdul (2004). "The development of the Health Sciences and Related Institutions During the First Six Centuries of Islam". ISoIT: 973–984.

- Miller, Andrew C. (December 2006). "Jundi-Shapur, bimaristans, and the rise of academic medical centres". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (12): 615–617. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.12.615. PMC 1676324. PMID 17139063. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013.

- Prioreschi, Plinio (2001). A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine (1st ed.). Omaha, NE: Horatius Press. p. 394. ISBN 978-1-888456-04-2.

- Shanks, Nigel J.; Dawshe, Al-Kalai (January 1984). "Arabian medicine in the Middle Ages". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 77 (1): 60–65. PMC 1439563. PMID 6366229.

- O'Malley, Charles Donald (1970). The History of Medical Education: An International Symposium Held February 5-9, 1968, Volume 673. Berkeley, Univ. of Calif. Press: University of California Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0-520-01578-4.

- Gadelrab, Sherry (2011). "Discourses on Sex difference in medieval scholarly Islamic thought". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 66 (1): 40–81. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrq012. PMID 20378638.

- Cyril Elgood, "Tibb-Ul-Nabbi or Medicine of the Prophet," Osiris vol. 14, 1962. (selections): 60.

- Elgood, "Tibb-Ul-Nabbi or Medicine of the Prophet," 75, 90, 96, 105, 117.

- Elgood, "Tibb-Ul-Nabbi or Medicine of the Prophet," 172.

- Elgood, "Tibb-Ul-Nabbi or Medicine of the Prophet," 152-153.

- Verskin, Sara (6 April 2020). Barren Women: Religion and Medicine in the Medieval Middle East. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-059658-8.

- Pormann, Peter (15 May 2009). "The art of medicine: Female patients and practitioners in medieval Islam". The Lancet. 373: 3.

- Verskin, Sara (2017). "Barren Women: The Intersection of Biology, Medicine, and Religion in the Treatment of Infertile Women in the Medieval Middle East". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pormann, Peter (2009). "The Art of Medicine: female patients and practitioners in medieval Islam" (PDF). Perspectives. 373 (9675): 1598–1599. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60895-3. PMID 19437603. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- "Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts: The Art as a Profession". United States National Library of Medicine. 15 April 1998.

- Bademci, G (2006). "First illustrations of female "Neurosurgeons" in the fifteenth century by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu" (PDF). Neurocirugía. 17 (2): 162–165. doi:10.4321/s1130-14732006000200012.

- Shatzmiller, Mya (1994). Labour in the Medieval Islamic World. p. 353.

- The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 22:2 Mehmet Mahfuz Söylemez, The Jundishapur School: Its History, Structure, and Functions, p.3.

- Gail Marlow Taylor, The Physicians of Gundeshapur, (University of California, Irvine), p.7.

- Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p.7.

- Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p.3.

Bibliography

- Leclerc, Lucien (1876). Histoire de la médecine arabe. Exposé complet des traductions du grec. Les sciences en orient. Leur transmission à l'Occident par les traductions latines (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. 3. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2.

- Browne (1862-1926), Edward G. (2002). Islamic Medicine. Goodword Books. ISBN 978-81-87570-19-6.

- Dols, Michael W. (1984). Medieval Islamic Medicine: Ibn Ridwan's Treatise "On the Prevention of Bodily Ills in Egypt". Comparative Studies of Health Systems and Medical Care. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04836-2.

- Pormann, Peter E.; Savage-Smith, Emilie (2007). Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2066-1.

- Porter, Roy (2001). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00252-3.

- Saunders, John J. (1978). A History of Medieval Islam. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05914-5.

- Sezgin, Fuat (1970). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde [History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine] (in German). Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Ullmann, Manfred (1978). Islamic Medicine. Islamic Surveys. 11. Edinburgh Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-85224-325-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Medieval Islamic medicine. |

- Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine.

- Arabic Medical Manuscripts at the UCL Centre for the History of Medicine.

- Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts at the National Library of Medicine.

- Influence On the Historical Development of Medicine by Prof. Hamed Abdel-reheem Ead.

- Al-Zahrawi (Albucasis) – A light in the Middle Ages in Europe by Dr. Sharif Kaf Al-Ghazal

- Contagion – Perspectives from Pre-Modern Societies