Islam in Mali

Muslims currently make up approximately 95 percent of the population of Mali. The majority of Muslims in Mali are Malikite Sunni, influenced with Sufism.[1] Ahmadiyya and Shia branches are also present.[2]

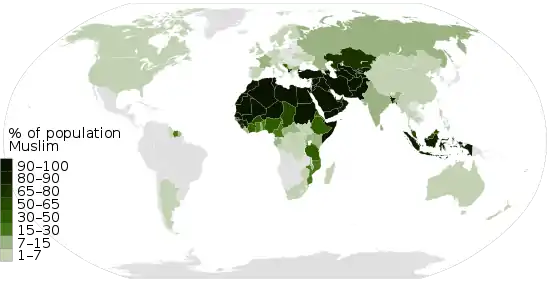

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

History

During the 9th century, Muslim Berber and Tuareg merchants brought Islam southward into West Africa. Islam also spread in the region by the founders of Sufi brotherhoods (tariqah). Conversion to Islam linked the West African savannah through belief in one God and similar new forms of political, social and artistic accoutrements. Cities including Timbuktu, Gao and Kano soon became international centers of Islamic learning.

The most significant of the Mali kings was Mansa Musa (1312–1337), who expanded Mali influence over the large Niger city-states of Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenné. Mansa Musa was a devout Muslim who was reported to have built various major mosques throughout the Mali sphere of influence; his gold-laden pilgrimage to Mecca made him a well-known figure in the historical record.

Muslims in Mali

Islam as practiced in the country until recently was reported to be relatively tolerant and adapted to local conditions. Women participated in economic and political activity, engaged in social interaction, and generally did not wear veils. Islam in Mali has absorbed mystical elements, ancestor veneration and the African Traditional Religion that still thrive. Many aspects of Malian traditional society encourage norms consistent with democratic citizenship, including tolerance, trust, pluralism, the separation of powers and the accountability of the leader to the governed.

Relations between the Muslim majority and the Christian and other religious minorities—including practitioners of African Traditional Religion were reported to be generally stable until recently, although there have been several cases of instability and tension in the past. It is relatively common to find adherents of a variety of faiths within the same family. Many followers of one religion usually attend religious ceremonies of other religions, especially weddings, baptisms, and funerals.

Since the 2012 imposition of Sharia rule in northern parts of the country, persecution of Christians in the north increased significantly and was described as severe by Open Doors which publishes the Christian persecution index; Mali appears as number 7 in the 2013 index list.[3][4]

Implementation of Sharia in the rebel-controlled north included banning of music, cutting off of hands or feet of thieves, stoning of adulterers and public whipping of smokers, alcohol drinkers and women who are not properly dressed.[5] In 2012, several Islamic sites in Mali were destroyed or damaged by vigilante activists linked to Al Qaeda which claimed that the sites represented "idol worship".[6]

There are foreign Islamic preachers that operate in the north of the country, while mosques associated with Dawa (an Islamist group) are located in Kidal, Mopti, and Bamako. The organization Dawa has gained adherents among the Bellah, who were once the slaves of the Tuareg nobles, and also among unemployed youth. The interest these groups have in Dawa is based on a desire to dissociate themselves from their former masters, and to find a source of income for the youth. The Dawa sect has a strong influence in Kidal, while the Wahabi movement has been reported to be steadily growing in Timbuktu. The country's traditional approach to Islam is relatively moderate, as reflected in the ancient manuscripts from the former University of Timbuktu.

In August 2003, a conflict erupted in the village of Yerere in Western Mali when traditional Sunni practitioners attacked Wahhabi Sunnis, who were building an authorized mosque.[7]

Other foreign missionary groups are Christian groups that are based in Europe and engaged in development work, primarily the provision of health care and education.

Status of religious freedom

The constitution provides for freedom of religion and does not permit any form of religious discrimination or intolerance by the government or individual persons. There is no state religion as the constitution defines the country as a secular state and allows for religious practices that do not pose a threat to social stability and peace.[1]

The government requires that all public associations, including religious associations, register with the government. However, registration confers no tax preference and no other legal benefits, and failure to register is not penalized in practice. Traditional indigenous religions are not required to register.[1]

A number of foreign missionary groups operate in the country without government interference. Both Muslims and non-Muslims are allowed to convert people freely.

The family law, including laws pertaining to divorce, marriage, and inheritance, are based on a mixture of local tradition and Islamic law and practice.

During presidential elections held in April and May 2002, the Government and political parties emphasized the secularity of the state. A few days prior to the elections, a radical Islamic leader called on Muslims to vote for former Prime Minister Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta. The High Council of Islam, the most senior Islamic body in the country, severely criticized the statement and reminded all citizens to vote for the candidate of their choice.

In January 2002, the High Council was created to coordinate religious affairs for the entire Muslim community and standardize the quality of preaching in mosques. All Muslim groups in the country currently recognize its authorize.

Extremism

Extremist worshippers of Islam have been responsible for some reprehensible acts in Mali, most notably what has been nicknamed the Battle of Gao, in which an extremist Muslim group, Ansar Dine began to destroy various World Heritage Sites. The most significant of these was the mausoleum of Sidi Mahmoud Ben Amar and in mausoleums around the capital, including that of Sidi Yahya, militants broke in and destroyed tombs.

Many towns in Mali are falling victim to extremist groups’ implementation of Sharia law, by which many African cultures and enjoyments have been denied.[5] A recent report in The Guardian revealed that extremist groups have banned music in certain regions and were known to turn up randomly in villages, armed with weaponry, to burn musical instruments and musical items on bonfires. One guitarist was threatened that his fingers would be chopped off if he ever showed his face in one town again.[5] On 18 May 2017, a man and a woman were stoned to death for living maritally without being married.[8] According to officials, the extremists first dig two holes, one for man and other for women, and the couple were buried up to their necks and then four extremists started throwing stones on them and continued throwing until they died from their wounds.[9] Public were invited to take part in this stoning. The couple were accused of violating Islamic law by living together without marriage.[10]

See also

References

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2015 - Mali". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity" (PDF). Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. August 9, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- Report points to 100 million persecuted Christians. Retrieved on 10 Jan 2013.

- OPEN DOORS World Watch list 2012

- Morgan, Andy (23 October 2012). "Mali: no rhythm or reason as militants declare war on music". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Hughes, Dana (2012-07-03). "Al Qaeda destroys Timbuktu shrines, ancient city's spirit". ABC News. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- "Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor - Mali". US Department of State. 2006-03-08. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "Unmarried couple stoned to death in Mali for breaking 'Islamic law'". The Independent. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "Unmarried Mali couple stoned to death for violating 'Islamic law'". The Telegraph. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "Unmarried couple stoned to death in Mali for 'violating Islamic law'". The Guardian. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

External links

- Watling, Jack; Raymond, Paul (26 November 2015). "The struggle for Mali". Guardian online. Retrieved 20 November 2016.