Islam in Europe

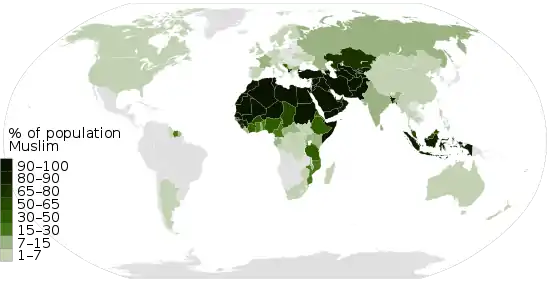

Islam is the second-largest religion in Europe after Christianity.[2] Although the majority of Muslim communities in Western Europe formed recently,[3] there are centuries-old Muslim societies in the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea, and Volga region.[4] The term "Muslim Europe" is used to refer to the Muslim-majority countries in the Balkans (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Kosovo) and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Russian Republics) that constitute of large populations of native White European Muslims, although the majority are secular.[4]

| 90–100% | |

| 70–80% | Kazakhstan |

| 50–70% | |

| 30–50% | North Macedonia |

| 10–20% | |

| 5–10% | |

| 4–5% | |

| 2–4% | |

| 1–2% | |

| < 1% |

Islam entered Southern Europe through the expansion of "Moors" of North Africa in the 8th–10th centuries; Muslim political entities existed firmly in what is today Spain, Portugal, Sicily, and Malta for several centuries. The Muslim community in these territories was converted or expelled by the end of the 15th century by Christian polities (see Reconquista). Islam expanded into the Caucasus through the Muslim conquest of Persia in the 7th century. The Ottoman Empire expanded into southeastern Europe, invading and conquering huge portions of the Serbian Empire, Bulgarian Empire, and all the remaining Byzantine Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. Over the centuries, the Ottoman Empire gradually lost almost all of its European territories, until it was defeated and eventually collapsed in 1922. Islam spread in Eastern Europe via the conversion of the Volga Bulgars, Cuman-Kipchaks, and later the Golden Horde and its successor khanates, with its various Muslim peoples called "Tatars" by the Russians.

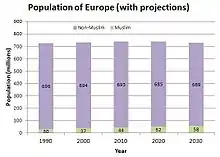

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, large numbers of Muslims immigrated to Western Europe.[3] By 2010, an estimated 44 million Muslims were living in Europe (6%), including an estimated 19 million in the EU (3.8%).[5] They are projected to comprise 8% by 2030.[6] They are often the subject of intense discussion and political controversy created by events such as terrorist attacks, the cartoons affair in Denmark, debates over Islamic dress, and ongoing support for right-wing populist parties that view Muslims as a threat to European culture. Such events have also fueled growing debate regarding the topic of Islamophobia, attitudes toward Muslims, and the populist right.[7]

History

The Muslim population in Europe is extremely diverse with varied histories and origins. Today, the Muslim-majority regions of Europe are Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Kosovo, parts of North Macedonia and Montenegro, as well as some Russian Republics in the North Caucasus and the Idel-Ural region.[4] These communities consist predominantly of indigenous White Europeans of the Muslim faith, whose religious tradition dates back several hundred years to the Middle Ages.[4] The transcontinental countries of Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan are also majority Muslim.

Moors, Al-Andalus, Sicily and Crete

Muslim forays into Europe began shortly after the religion's inception. Soon after the death of the prophet Muhammad in AD 632, the Muslim world expanded westwards, and within less than a century encompassed sizeable parts of what today is considered Europe. Muslim forces easily prevailed over the Byzantines in the crucial battles of Ajnâdayn (634) and Yarmûk (636)[8] and incorporated the province of Syria from them pushing relentlessly to the north and west. At the same time, consolidation of the hold of Islam in North Africa was soon to be followed by incursions into what is now Europe as Muslim armies raided and eventually conquered territories leading to the establishment of Muslim states on the European continent, some of which were quite long-lived. A short-lived invasion of Byzantine Sicily by a small Arab and Berber force that landed in 652 was the prelude of a series of incursions; from the eighth century to the fifteenth, Muslims ruled parts of the Iberian Peninsula, southern Italy, southern France and, several Mediterranean islands,[9] while in the East, incursions into a much reduced in territory and weakened Byzantine Empire continued unabated. In the 720s and 730s Muslim forces fought and raided north of the Pyrenees, well into what is now France, reaching as north as Tours where they were eventually repelled by the Franks in 732 to their Iberian and North African territories.

Muslims established various emirates in Europe after the conquering of Al-Andalus. One notable emirate was Emirate of Crete, the state existed on the Mediterranean island of Crete from the late 820s to the Byzantine reconquest of the island in 961. The other was Emirate of Sicily, an emirate on Sicily which existed from 831 to 1091.

Islam gained its first genuine foothold in continental Europe from 711 onward, with the Umayyad conquest of Hispania. The Arabs renamed the land Al-Andalus, which expanded to include the larger parts of what is now Portugal and Spain, excluding the northern highlands. Scholars suggest that Al-Andalus had a Muslim majority by the 10th century after most of the local population willingly converted to Islam.[10] This coincided with the La Convivencia period of the Iberian Peninsula as well as the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain. The Christian counter-offensive known as the Reconquista began in the early 8th century, when Muslim forces managed to temporarily push into southern France. Slowly, the Christian forces began a re-conquest of the fractured Taifa kingdoms of Al-Andalus. There was still a Muslim presence north of Spain, especially in Fraxinet all the way into Switzerland until the 10th century.[11] Muslim forces under the Aghlabids conquered Sicily after a series of expeditions spanning 827–902, and had notably raided Rome in 846. The Emirate of Sicily was established in 965. Arabs held onto southern Italy until their expulsion by the Normans in 1072. By 1236, practically all that remained of Muslim Spain was the southern province of Granada.

The Arabs imposed Sharia, thus, the Latin- and Greek-speaking Christian communities, as well as a community of Jews, had limited freedom of religion under the Muslims as dhimmi (protected non-Muslims). They were required to pay jizya (poll tax levied on able bodied men only), but exempt from the Muslim tax of zakat. These taxes marked their status as subject to Muslim rule, albeit in exchange for protection against foreign and internal aggression.

Cultural impact and interaction

Overthrown by the Abbasids, the deposed Umayyad caliph Abd al-Rahmân I fled Damascus in 756 and established an independent emirate in Córdoba. His dynasty consolidated the presence of Islam in Al-Andalus (as Spain was known to Muslims). By the time of the reign of Abd al-Rahmân II (822–852) Córdoba was becoming one of the biggest and most important cities in Europe. Umayyad Spain had become a centre of the Muslim world that rivaled the Muslim cities of Damascus and Baghdad. "The emirs of Córdoba built palaces reflecting the confidence and vitality of Andalusi Islam, minted coins, brought to Spain luxury items from the East, initiated ambitious projects of irrigation and transformed agriculture, reproduced the style and ceremony of the Abbasid court ruling in the East and welcomed famous scholars, poets and musicians from the rest of the Muslim world.[12] But, the most significant impact of the Emirate was its cultural influence over the non-Muslim local population. An "elegant Arabic" became the preferred language of the educated – Muslim, Christian and Jewish, the readership of Arabic books increased rapidly, and Arabic romance and poetry became extremely popular.[13] The popularity of literary Arabic was just one aspect of the Arabization of the Christians of the Iberian Peninsula which led contemporaries to refer to the affected populations as "Mozarabs (mozárabes in Spanish; moçárabes in Portuguese – from the Arabic: musta’rib; ‘like Arabs’, ‘Arabicized’"[14]

Arabic-speaking Christian scholars saved influential pre-Christian texts and introduced aspects of medieval Islamic culture[15][16][17] (including the arts,[18][19][20] economics,[21] science and technology).[22][23] (See Latin translations of the 12th century and Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe for more information).

Muslim rule endured in the Emirate of Granada, from 1238 as a vassal state of the Christian Kingdom of Castile, until the completion of La Reconquista in 1492.[24] The Moriscos (Moorish in Spanish) were finally expelled from Spain between 1609 (Castile) and 1614 (rest of Spain), by Philip III during the Spanish Inquisition.

Throughout the 16th to 19th centuries, the Barbary States sent pirates to raid nearby parts of Europe in order to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in northern Africa throughout the Renaissance period.[25][26] According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th centuries, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves. These slaves were captured mainly from the crews of captured vessels[27] and from coastal villages in Spain and Portugal, and from farther places like Italy, France, or England, the Netherlands, Ireland, the Azores Islands, and even Iceland.[25]

For a long time, until the early 18th century, the Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East.[28] The Crimean Tatars frequently mounted raids into the Danubian principalities, Poland–Lithuania, and Russia to enslave people whom they could capture.[29]

Eastern Europe

Hungary

The Böszörmény Muslims formed an early community of Muslims in Hungary. Their biggest settlement was near the town of present-day Orosháza in the central part of the Hungarian Kingdom. At that time this settlement entirely populated by Muslims was probably one of the biggest settlements of the Kingdom. This and several other Muslim settlements were all destroyed and their inhabitants massacred during the 1241 Mongol invasion of Hungary.

Russia and Ukraine

In the mid-7th century AD, following the Muslim conquest of Persia, Islam spread into areas that would later become part of Russia.[30] There are accounts of the trade connections between Muslims and the Rus', apparently people from the Baltic region who made their way towards the Black Sea through Central Russia. During his journey to Volga Bulgaria in 921–922, Ibn Fadlan observed the Rus', claiming that some had converted to Islam. "They are very fond of pork and many of them who have assumed the path of Islam miss it very much." The Rus' also relished their nabidh, a fermented drink which Ibn Fadlan often mentioned as part of their daily fare.[31]

The Mongols began their conquest of Rus', of Volga Bulgaria, and of the Cuman-Kipchak Confederation (parts of present-day Russia and Ukraine) in the 13th century. After the Mongol empire split, the eastern European section became known as the Golden Horde. Although not originally Muslim, the western Mongols adopted Islam as their religion in the early-14th century under Berke Khan, and later Uzbeg Khan established it as the official religion of the state. Much of the mostly Turkic-speaking population of the Horde, as well as the small Mongol aristocracy, became Islamized (if they were not already Muslim, like the Volga Bulgars) and became known to Russians and Europeans as the Tatars. More than half[32] of the European portion of what is now Russia and Ukraine came under the suzerainty of Muslim Tatars and Turks from the 13th to the 15th centuries. The Crimean Khanate became a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire in 1475 and subjugated what remained of the Great Horde by 1502. The Russian Tsar Ivan the Terrible conquered the Muslim Khanate of Kazan in 1552.

Belarus and Poland–Lithuania

Lipka Tatar Muslims of Belarus and Poland–Lithuania.[33][34][35][36][37] The material of their Mosques is wood.[38]

Balkans

Seljuks

As a result of Babai revolt, in 1261, one of the Turkoman dervish Sari Saltuk was forced to take refuge in the Byzantine Empire, alongside 40 Turkoman clans. He was settled in Dobruja, whence he entrered the service of the powerful Muslim Mongol emir, Nogai Khan. Sari Saltuk became the hero of an epic, as a dervish and ghazi spreading Islam into Europe.[39]

Ottomans

.JPG.webp)

The Ottoman Empire began its expansion into Europe by taking the European portions of the Byzantine Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries up until the 1453 capture of Constantinople, establishing Islam as the state religion in the region. The Ottoman Empire continued to stretch northwards, taking Hungary in the 16th century, and reaching as far north as the Podolia in the mid-17th century (Peace of Buczacz), by which time most of the Balkans was under Ottoman control. Ottoman expansion in Europe ended with their defeat in the Great Turkish War. In the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), the Ottoman Empire lost most of its conquests in Central Europe. The Crimean Khanate was later annexed by Russia in 1783.[40] Over the centuries, the Ottoman Empire gradually lost almost all of its European territories, until its collapse in 1922, when the former empire was transformed into the nation of Turkey.

Between 1354 (when the Ottomans crossed into Europe at Gallipoli) and 1526, the Empire had conquered the territory of present-day Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Bosnia, and Hungary. The Empire laid siege to Vienna in 1683. The intervention of the Polish King broke the siege, and from then afterwards the Ottomans battled the Habsburg Emperors until 1699, when the Treaty of Karlowitz forced them to surrender Hungary and portions of present-day Croatia, Slovenia, and Serbia. From 1699 to 1913, wars and insurrections pushed the Ottoman Empire further back until it reached the current European border of present-day Turkey.

For most of this period, the Ottoman retreats were accompanied by Muslim refugees from these provinces (in almost all cases converts from the previous subject populations), leaving few Muslim inhabitants in Hungary, Croatia, and the Transylvania region of present-day Romania. Bulgaria remained under Ottoman rule until around 1878, and currently its population includes about 131,000 Muslims (2001 Census) (see Pomaks).

Bosnia was conquered by the Ottomans in 1463, and a large portion of the population converted to Islam in the first 200 years of Ottoman domination. By the time Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia in 1878, the Habsburgs had shed the desire to re-Christianize new provinces. As a result, a sizable Muslim population in Bosnia survived into the 20th century. Albania and the Kosovo area remained under Ottoman rule until 1913. Prior to the Ottoman conquest, the northern Albanians were Roman Catholic and the southern Albanians were Christian Orthodox, but by 1913 the majority were Muslim.

Conversion to Islam

Apart from the effect of a lengthy period under Ottoman domination, many of the subject population were forcefully converted to Islam as a result of a deliberate move by the Ottomans as part of a policy of ensuring the loyalty of the population against a potential Venetian invasion. However, Islam was spread by force in the areas under the control of the Ottoman Sultan through devşirme and jizya.[43][44] Rather Arnold explains Islam's spread by quoting 17th-century author Johannes Scheffler who stated:

Meanwhile he (i.e. the Turk) wins (converts) by craft more than by force, and snatches away Christ by fraud out of the hearts of men. For the Turk, it is true, at the present time compels no country by violence to apostatise; but he uses other means whereby imperceptibly he roots out Christianity... What then has become of the Christians? They are not expelled from the country, neither are they forced to embrace the Turkish faith: then they must of themselves have been converted into Turks.[45]

Cultural influences

Islam piqued interest among European scholars, setting off the movement of Orientalism. The founder of modern Islamic studies in Europe was Ignác Goldziher, who began studying Islam in the late 19th century. For instance, Sir Richard Francis Burton, 19th-century English explorer, scholar, and orientalist, and translator of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, disguised himself as a Pashtun and visited both Medina and Mecca during the Hajj, as described in his book A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah.

Islamic architecture influenced European architecture in various ways (for example, the Türkischer Tempel synagogue in Vienna). During the 12th-century Renaissance in Europe, Latin translations of Arabic texts were introduced.

Twentieth century

Muslim emigration to metropolitan France surged during the Algerian War of Independence. In 1961, the West German Government invited first Gastarbeiters and similar contracts were offered by Switzerland; some of these migrant workers came from majority-Muslim countries such as Turkey. Migrants came to Britain from its majority-Muslim former colonies Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Current demographics

The exact number of Muslims in Europe is unknown. According to estimates by the Pew Forum, the total number of Muslims in Europe (excluding Turkey) in 2010 was about 44 million (6% of the total population), including 19 million (3.8% of the population) in the European Union.[5] A 2010 Pew Research Center study reported that 2.7% of the world's Muslim population live in Europe.[46]

The Turks form the largest ethnic group in European Turkey (as well as the Republic of Turkey as a whole) and Northern Cyprus, they also form centuries-old minority groups in other post-Ottoman nation states within the Balkans (i.e. the Balkan Turks) where they form the largest ethnic minority in Bulgaria and the second largest minority in North Macedonia. Meanwhile, in the diaspora, the Turks form the largest ethnic minority group in Austria, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands.[47] In 1997 there was approximately 10 million Turks living in Western Europe and the Balkans (i.e. excluding Northern Cyprus and Turkey).[48] By 2010 up to 15 million Turks were living in the European Union (i.e. excluding Turkey and several Balkan and Eastern European countries which are not in the EU).[49] According to Dr Araks Pashayan 10 million "Euro-Turks" alone were living in Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium in 2012.[50] In addition, substantial Turkish communities have been formed in the United Kingdom, Austria, Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, Italy, Liechtenstein, Finland, and Spain. Meanwhile, there is over one million Turks still living in the Balkans (especially in Bulgaria, Greece, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Romania),[51] and approximately 400,000 Meskhetian Turks in the Eastern European regions of the Post-Soviet states (i.e. Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine).[52]

Estimates of the percentage of Muslims in Russia (the biggest group of Muslims in Europe) vary from 5[53] to 11.7%,[5] depending on sources. It also depends on if only observant Muslims or all people of Muslim descent are counted.[54]

58.8% of Albania adheres to Islam, making it the largest religion in the country. The majority of Albanian Muslims are Secular Sunni with a significant Bektashi Shia minority.[55] The percentage is 93.5% in Kosovo,[56] 39.3% in North Macedonia[57][58] (according to the 2002 Census, 46.5% of the children aged 0–4 were Muslim in Macedonia)[59] and 50.7% in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[60] In transcontinental countries such as Turkey 99%, and 93% in Azerbaijan[61] of the population is Muslim respectively. According to the 2011 census, 20% of the total population in Montenegro are Muslims.[62] In Russia, Moscow is home to an estimated 1.5 million Muslims.[63][64][65]

Darren E. Sherkat questioned in Foreign Affairs whether some of the Muslim growth projections are accurate as they do not take into account the increasing number of non-religious Muslims. Quantitative research is lacking, but he believes the European trend mirrors the American: data from the General Social Survey in the United States show that 32 percent of those raised Muslim no longer embrace Islam in adulthood, and 18 percent hold no religious identification.[66]

A survey conducted by Pew Research Center in 2016 found that Muslims make up 4.9% of all Europe's population.[67] According to a same study conversion does not add significantly to the growth of the Muslim population in Europe, with roughly 160,000 more people leaving Islam than converting into Islam between 2010 and 2016.[67]

| Country | Estimated % of Muslims among total population in 2016[67] |

|---|---|

| Cyprus | 25.4 |

| Bulgaria | 11.1 |

| France | 8.8 |

| Sweden | 8.1 |

| Belgium | 7.6 |

| Netherlands | 7.1 |

| Austria | 6.9 |

| United Kingdom | 6.3 |

| Germany | 6.1 |

| Switzerland | 6.1 |

| Norway | 5.7 |

| Greece | 5.7 |

| Denmark | 5.4 |

| Italy | 4.8 |

| Slovenia | 3.8 |

| Luxembourg | 3.2 |

| Finland | 2.7 |

| Spain | 2.6 |

| Croatia | 1.6 |

| Ireland | 1.4 |

Projections

A Pew Research Center study, published in January 2011, forecast an increase of Muslims in European population from 6% in 2010 to 8% in 2030.[5] The study also predicted that Muslim fertility rate in Europe would drop from 2.2 in 2010 to 2.0 in 2030. On the other hand, the non-Muslim fertility rate in Europe would increase from 1.5 in 2010 to 1.6 in 2030.[5] Another Pew study published in 2017 projected that in 2050 Muslims will make 7.4% (if all migration into Europe were to immediately and permanently stop - a "zero migration" scenario) up to 14% (under a "high" migration scenario) of Europe's population.[68] Data from the 2000s for the rates of growth of Islam in Europe showed that the growing number of Muslims was due primarily to immigration and higher birth rates.[69]

In 2017, Pew projected that the Muslim population of Europe would reach a level between 7% and 14% by 2050. The projections depend on the level of migration. With no net migration, the projected level was 7%; with high migration, it was 14%. The projections varied greatly by country. Under the high migration scenario, the highest projected level of any historically non-Muslim country was 30% in Sweden. By contrast, Poland was projected to remain below 1%.[70]

In 2006, the conservative Christian historian Philip Jenkins, in an article for the Foreign Policy Research Institute thinktank, wrote that by 2100, a Muslim population of about 25% of Europe's population was "probable"; Jenkins stated this figure did not take account growing birthrates amongst Europe's immigrant Christians, but did not give details of his metholodogy.[71] in 2010, Eric Kaufmann, professor of politics at Birkbeck, University of London said that "In our projections for Western Europe by 2050 we are looking at a range of 10-15 per cent Muslim population for most of the high immigration countries – Germany, France, the UK";[72] he argued that Islam was expanding, not because of conversion to Islam, but primarily due to the religion's "pro-natal" orientation, where Muslims tend to have more children.[73] Other analysts are skeptical about the accuracy of the claimed Muslim population growth, stating that because many European countries do not ask a person's religion on official forms or in censuses, it has been difficult to obtain accurate estimates, and arguing that there has been a decrease in Muslim fertility rates in Morocco, the Netherlands and Turkey.[74]

| Country | Muslims (official) | Muslims (estimation) | % of total population | % of World Muslim population | Community origin (predominant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,646,128 | 2,601,000 (Pew 2011) | 58.79 (official);[75] 82.1 (Pew 2011) | 0.1 | Indigenous (Albanians) | |

| N/A | < 1,000 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 700,000 (2017 study)[76] | 8[76] | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 19,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.2 | < 0.1 | Immigrant and Indigenous (Lipka Tatars) | |

| N/A | 781,887 (2015 est.)[77] | 5.9[78]–7[77] | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 1,790,454 (2016 census) | 1,564,000 (Pew 2011) | 50.7 (official);[79] 41.6 (Pew 2011) | 0.1 | Indigenous (Bosniaks, Romani, Croats, Turks) | |

| 577,000 (2011 census)[80] | 1,002,000 (Pew 2011) | 7.8 (official); 13.4 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Indigenous (Pomaks, Turks) | |

| N/A | 56,000 (Pew 2011) | 1.3 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant and Indigenous (Bosniaks, Croats) | |

| N/A | 200,000 (Pew 2011) | 22.7 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Indigenous (Turks) | |

| N/A | 4,000 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 226,000 (Pew 2011) | 4.1 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 1,508 | 2,000 | 0.1 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | < 1,000 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 65,000 (Pew 2016) | 0.5 (Pew 2016) | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 4,704,000 (Pew 2011) | 7.5 (Pew 2011) | 0.3 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 4,119,000 (Pew 2011); 4,700,000 (CIA)[81] | 5 (Pew 2011) | 0.2 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 527,000 (Pew 2011) | 4.7 (Pew 2011) | <0.1 | Indigenous (minority) | |

| 5,579[82] | 25,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.3 (Pew 2011) | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 770[83] | < 1,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.2[83] | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 70,158 (2016 census) | 43,000 (Pew 2011) | 1.3[84] | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 1,583,000 (Pew 2011) | 2.3;[85] 2.6 (Pew 2011) | 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 1,584,000 (CIA);[86] 2,104,000 (Pew 2011) | 95.6 | 0.1 | Indigenous (Albanians, Bosniaks, Gorani, Turks) | |

| N/A | 2,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.1 | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 2,000 (Pew 2011) | 4.8 (Pew 2011) | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 3,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.1 (Pew 2011) | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 11,000 (Pew 2011) | 2.3 (Pew 2011) | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 1,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.3 (Pew 2011) | <0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 15,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.4 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | < 1,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.5 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 118,477 (2011)[87] | 116,000 (Pew 2011) | 19.11[87] | < 0.1 | Indigenous (Bosniaks, Albanians, "Muslims") | |

| N/A | 914,000 (Pew 2011) | 5[88] – 6[78] | 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 713,000 (Pew 2011) | 33 [89][90] | <0.1 | Indigenous (Albanians, Turks, Romani, Torbeši) | |

| N/A | 106,700–194,000 (Brunborg & Østby 2011);[91] | 2–4[91] | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 20,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.1 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant and Indigenous (Lipka Tatars) | |

| N/A | 65,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.6 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 73,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.3 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant and indigenous (Turks and Tatars) | |

| N/A | 16,379,000 (Pew 2011) | 11.7 (Pew 2011); 15 (CIA)[92] | 1.0 | Indigenous | |

| N/A | < 1,000 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 228,828 (2011) | 280,000 (Pew 2011) | 3.1 (CIA);[93] 3.7 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Indigenous (Bosniaks, "Muslims", Romani, Albanians, Gorani, Serbs) | |

| 10,866 | 4,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.1 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 73,568 | 49,000 (Pew 2011) | 2.4 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| 1,887,906 | 1,021,000 (Pew 2011) | 4.1[94] | 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 450,000–500,000 (2009 DRL);[95] 451,000 (Pew 2011) | 5[95] | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 433,000 | 5.7 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Immigrant | |

| N/A | 393,000 (Pew 2011) | 0.9 (Pew 2011) | < 0.1 | Indigenous (Crimean Tatars)[96] | |

| 3,106,368 | 2,869,000 (Pew 2011) | 4.6 (Pew 2011) | 0.2 | Immigrant | |

Vatican City |

0 | 0

(pew 2011) |

0 (pew 2011) | 0 | None |

Religiosity

According to Deutsche Welle, immigrants from Muslim countries remain strongly religious in a trend which continues across generations. In the UK, 64% identify as "highly religious", 42% in Austria, 33% in France and 26% in Switzerland.[97]

A 2005 Université Libre de Bruxelles study estimated that about 10% of the Muslim population in Belgium are "practicing Muslims".[98] In 2009, only 24% of Muslims in the Netherlands attended mosque once a week according to a survey.[99] According to the same 2004 survey, they found that the importance of Islam in the lives of Dutch Muslims, particularly of second-generation immigrants was decreasing. According to a survey, only 33% of French Muslims who were interviewed said they were religious believers. That figure is the same as that obtained by the INED/INSEE survey in October 2010.[100]

Society

Mosques

Islamic dress

According to Pew Research Center in 2018, most Europeans favour restrictions on face-covering veils.[102] An estimated 13 out of 15 favoring a ban of face-covering veils in Western Europe. As opposed to politicians and intellectuals, people perceive Islamic dress to not represent religious symbols but a repressive ideology in the form of Islamism which intends to extend its influence into family, society and politics.[103]

Honor killings

According to a study investigating 67 honor killings in Europe 1989-2009 by Phyllis Chesler, 96% of honor murder perpetrators in Europe were Muslim and 68% of victims were tortured before they died.[104]

Muslim girls and women are murdered for honor in both the Western world and elsewhere for refusing to wearing the hijab or for not wearing it strictly. Allegations of unacceptable "Westernization" of a Muslim woman accounted for 71% of the justifications of honor killings in Europe.[104]

Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism

A 2013 study conducted by Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB) found that Islamic fundamentalism was widespread among Muslims in Europe. The study conducted a poll among Turkish immgrants to six European countries: Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, and Sweden. In the first four countries also Moroccan immigrants were interviewed.[105] Fundamentalism was defined as: the belief that believers should return to the eternal and unchangeable rules laid down in the past; that these rules allow only one interpretation and are binding for all believers; and that religious rules have priority over secular laws. Two thirds of Muslims the majority responded that religious rules are more important than civil laws and three quarters rejecting religious pluralism within Islam.[106] Of the respondents, 44% agreed to all three statements. Almost 60% responded that Muslims should return to the roots of Islam, 75% thought there was only one possible interpretation of the Quran.[105]

The conclusion was that religious fundamentalism is much more prevalent among European Muslims than among Christian natives. Perceived discrimination is a marginal predictor of religious fundamentalism.[105] The perception that Western governments are inherently hostile towards Islam as a source of identity is prevailing among some European Muslims. However, a recent study shows that this perception significantly declined after the emergence of ISIS, particularly among the youth, and highly educated European Muslims.[107] The difference between countries defies a "reactive religious fundamentalism", where fundamentalism is viewed as a reaction against lacking rights and privileges for Muslims. Instead, it was found that Belgium which has comparatively generous policies towards Muslims and immigrants in general also had a relatively high level of fundamentalism. France and Germany which have restricitive policies had lower levels of fundamentalism.[105]

In 2017, the EU Counter-terrorism Coordinator Gilles de Kerchove stated in an interview that there were more than 50000 radicals and jihadists in Europe.[108] In 2016, French authorities stated that 15000 of the 20000 individuals on the list of security threats belong to Islamist movements.[109] In the United Kingdom, authorities estimate that 23000 jihadists reside in the country, of which about 3000 are actively monitored.[110] In 2017, German authorities estimated that there were more than 10000 militant salafists in the country.[111]

Attitudes towards Muslims

| Part of a series on |

| Islamophobia |

|---|

|

The extent of negative attitudes towards Muslims varies across different parts of Europe.

The European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia reports that the Muslim population tends to suffer Islamophobia all over Europe, although the perceptions and views of Muslims may vary.[113]

In 2005 according to the Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau annual report, half the Dutch population and half the Moroccan and Turkish minorities stated that the Western lifestyle cannot be reconciled with that of Muslims.[114]

A 2015 poll by the Polish Centre for Public Opinion Research found that 44% of Poles have a negative attitude towards Muslims, with only 23% having a positive attitude towards them. Furthermore, a majority agreed with statements like "Muslims are intolerant of customs and values other than their own." (64% agreed, 12% disagreed), "Muslims living in Western European countries generally do not acquire customs and values that are characteristic for the majority of the population of that country." (63% agreed, 14% disagreed), "Islam encourages violence more than other religions." (51% agreed, 24% disagreed).[115]

A February 2017 poll of 10 000 people in 10 European countries by Chatham House found on average a majority were opposed to further Muslim immigration, with opposition especially pronounced in Austria, Poland, Hungary, France and Belgium. Of the respondents, 55% were opposed, 20% offered no opinion and 25% were in favour of further immigration from Muslim-majority countries. The authors of the study add that these countries, except Poland, had in the preceding years suffered jihadist terror attacks or been at the centre of a refugee crisis. They also mention that in most of the polled countries the radical right has political influence.[116]

According to a study in 2018 by Leipzig University, 56% of Germans sometimes thought the many Muslims made them feel like strangers in their own country, up from 43% in 2014. In 2018, 44% thought immigration by Muslims should be banned, up from 37% in 2014.[117]

Employment

According to a WZB report investigating Muslims in Germany, France, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Belgium and Switzerland, Muslims in Europe generally have higher levels of unemployment which is to a great part caused by the lack of language skills, the lack of inter-ethnic social ties and a traditional view of gender roles where women are not to work outside the home. Discrimination from employers caused a small part of the unemployment.[118]

See also

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

- A Common Word Between Us and You

- Antemurale Christianitatis

- Early Muslim conquests

- Islam by country

- Islamic culture

- Islamic dress in Europe

- Islamic feminism

- Islamism

- Islamophobic incidents

- List of cities in the European Union by Muslim population

- List of mosques in Europe

- Ottoman wars in Europe

- Persecution of Muslims

- Turks in Europe

- Catholic–Muslim Forum

- European Council for Fatwa and Research

- Muslim Council for Cooperation in Europe

References

- "Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050". Pew Research Center. 12 April 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Global religious futures Europe

- Cesari, Jocelyne (January–June 2002). "Introduction - "L'Islam en Europe: L'Incorporation d'Une Religion"". Cahiers d'Études sur la Méditerranée Orientale et le monde Turco-Iranien (in French). Paris: Éditions de Boccard. 33: 7–20. doi:10.3406/CEMOT.2002.1623. S2CID 165345374. Retrieved 21 January 2021 – via Persée.fr.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Cesari, Jocelyne, ed. (2014). "Part III: The Old European Land of Islam". The Oxford Handbook of European Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 427–616. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199607976.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-960797-6. LCCN 2014936672. S2CID 153038977.

- Pew 2011.

- The Future of the Global Muslim Population (Report). Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Goodwin, Matthew J.; Cutts, David; Janta-Lipinski, Laurence (September 2014). "Economic Losers, Protestors, Islamophobes or Xenophobes? Predicting Public Support for a Counter-Jihad Movement". Political Studies. 64: 4–26. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12159. S2CID 145753701.

- Tolan, John Victor (2002). Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 32. ISBN 0231123337.

- Sofos, Spyros; Tsagarousianou, Roza (2013). Islam in Europe: Public Spaces and Civic Networks. Basingstoke: Palgrave. p. 31. ISBN 9781137357779.

- Hourani 2002, p. 42.

- Manfred, W: "International Journal of Middle East Studies", pages 59-79, Vol. 12, No. 1. Middle East Studies Association of North America, Aug 1980.

- Sofos, Spyros; Tsagarousianou, Roza (2013). Islam in Europe: Public Spaces and Civic Networks. Basingstoke: Palgrave. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9781137357786.

- Southern, R.W. (1962). Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 21–12. ISBN 9780674435667.

- Sofos, Spyros; Tsagarousianou, Roza (2013). Islam in Europe: Public Spaces and Civic Networks. Basingstoke: Palgrave. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9781137357786.

- Hill, Donald. Islamic Science and Engineering. 1993. Edinburgh Univ. Press. ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p.4

- Brague, Rémi (2009-04-15). The Legend of the Middle Ages. p. 164. ISBN 9780226070803. Retrieved 11 Feb 2014.

- Ferguson, Kitty (3 March 2011). Pythagoras: His Lives and the Legacy of a Rational Universe. Icon Books Limited. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-1-84831-250-0.

It was in the Near and Middle East and North Africa that the old traditions of teaching and learning continued, and where Christian scholars were carefully preserving ancient texts and knowledge of the ancient Greek language.

- Islamic art and architecture History.com

- Carole Hillenbrand. The Crusades: Islamic perspectives, Routledge, 2000, p. 386

- Hillenbrand, p. 388

- Savory; p. 195-8

- Hyman and Walsh Philosophy in the Middle Ages Indianapolis, 3rd edition, p. 216

- Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach, Editors, Medieval Islamic Civilization Vol.1, A - K, Index, 2006, p. 451

- Hourani 2002, p. 41.

- "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast".

- "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates by Christopher Hitchens, City Journal Spring 2007".

- Milton, G (2005) White Gold: The Extraordinary Story of Thomas Pellow And Islam's One Million White Slaves, Sceptre, London

- "The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves" (PDF). Eizo Matsuki, Mediterranean Studies Group at Hitotsubashi University.

- "Historical survey > Slave societies". Encyclopædia Britannica,

- Hunter, Shireen (2016) [2004]. Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 9781315290119.

It is difficult to establish exactly when Islam first appeared in Russia because the lands that Islam penetrated early in its expansion were not part of Russia at the time, but were later incorporated into the expanding Russian Empire. Islam reached the Caucasus region in the middle of the seventh century as part of the Arab conquest of the Iranian Sassanian Empire.

- "Vikings in the East, Remarkable Eyewitness Accounts". Archived from the original on 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- Encarta, Mongol Invasion of Russia. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29.

- "Poland's Lipka Tatars: A Model For Muslims In Europe?". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- "The mosques of Lithuania". The Economist. 14 September 2015.

- ""Sarmatism" and Poland's national consciousness - Visegrad Insight".

- "February - 2015 - Visegrad Insight".

- "Photographer captures the essence of Islam in Europe". Aquila Style.

- "Mosques of Europe: the social, theological and geographical aspects". Aquila Style.

- Halil Inalcik, (1973), The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600 (The Ottoman Empire), p. 187

- "Avalanche Press". Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Rossos, Andrew (2008). "Ottoman Reform and Decline (c. 1800–1908)" (PDF). Macedonia and the Macedonians.

- Nasuh, Matrakci (1588). "Janissary Recruitment in the Balkans". Süleymanname, Topkapi Sarai Museum, Ms Hazine 1517. Archived from the original on 2018-12-03. Retrieved 2015-02-14.

- Basgoz, I. & Wilson, H. E. (1989), The educational tradition of the Ottoman Empire and the development of the Turkish educational system of the republican era. Turkish Review 3(16), 15

- The preaching of Islam: history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pp. 135-144

- Scheffler, Johannes (1663). Türcken-Schrifft Von den Ursachen der Türkischen Überziehung. (trans. Writing on the Turks: Of the causes of the Turkish invasion"). as quoted in Sir Thomas Walker Arnold (1896). The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith., pg. 158

- The Global Religious Landscape: Muslims, Pew Research Center, 18 December 2012

- Al-Shahi, Ahmed; Lawless, Richard (2013), "Introduction", Middle East and North African Immigrants in Europe: Current Impact; Local and National Responses, Routledge, p. 13, ISBN 978-1136872808

- Bayram, Servet; Seels, Barbara (1997), "The Utilization of Instructional Technology in Turkey", Educational Technology Research and Development, Springer, 45 (1): 112, doi:10.1007/BF02299617, S2CID 62176630,

There are about 10 million Turks living in the Balkan area of southeastern Europe and in western Europe at present.

- 52% of Europeans say no to Turkey's EU membership, Aysor, 2010, retrieved 7 November 2020,

This is not all of a sudden, says expert at the Center for Ethnic and Political Science Studies, Boris Kharkovsky. “These days, up to 15 million Turks live in the EU countries...

- Pashayan, Araks (2012), "Integration of Muslims in Europe and the Gülen", in Weller, Paul; Ihsan, Yilmaz (eds.), European Muslims, Civility and Public Life: Perspectives On and From the Gülen Movement, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-4411-0207-2,

There are around 10 million Euro-Turks living in the European Union countries of Germany, France, the Netherlands and Belgium.

- Dursun-Özkanca, Oya (2019), Turkey–West Relations: The Politics of Intra-alliance Opposition, Cambridge University Press, p. 40, ISBN 978-1108488624,

One-fifth of the Turkish population is estimated to have Balkan origins. Additionally, more than one million Turks live in Balkan countries, constituting a bridge between these countries and Turkey.

- Al Jazeera (2014). "Ahıska Türklerinin 70 yıllık sürgünü". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2016-07-05.

- by example only 6% of the Russian population is Islamic

- "What is the weight of Islam in France ?". Les décodeurs (Le Monde). January 21, 2015.

- 2011 Albanian census

- Kettani, Houssain (2010). "Muslim Population in Europe: 1950 – 2020" (PDF). International Journal of Environmental Science and Development vol. 1, no. 2, p. 156. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050" in: Pew Research Center, Retrieved 10 November 2016

- Republic of Macedonia, in: Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures, Retrieved 10 November 2016

- Census of Pupulation, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002, p. 518

- 2013 Census, http://popis2013.ba/

- "Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the UK, Country Profile 2007, p.4" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). Monstat. pp. 14, 15. Retrieved October 16, 2016. For the purpose of the chart, the categories 'Islam' and 'Muslims' were merged.

- The rise of Russian Muslims worries Orthodox Church, The Times, 5 August 2005

- Don Melvin, "Europe works to assimilate Muslims"Archived 2005-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 2004-12-17

- Tolerance and fear collide in the Netherlands, UNHCR, Refugees Magazine, Issue 135 (New Europe)

- Sherkat, Darren E. (22 June 2015). "Losing Their Religion: When Muslim Immigrants Leave Islam". Foreign Affairs.

- Hackett, Conrad (November 29, 2017), "5 facts about the Muslim population in Europe", Pew Research Center

- "Europes growing muslim-population - Pew Research Center". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 29 November 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- "Muslims in Europe: Country guide". BBC News. 2005-12-23. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- Lipka, Michael (December 4, 2017). "Europe's Muslim population will continue to grow – but how much depends on migration". Pew Center.

- Philip Jenkins, "Demographics, Religion, and the Future of Europe", Orbis: A Journal of World Affairs, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 533, summer 2006

- "Battle of the Babies - New Humanist".

- "Think religion is in decline? Look at who is 'going forth and multiplying'". 12 October 2014.

- Mary Mederios Kent, Do Muslims have more children than other women in western Europe? Archived 2008-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, Population Reference Bureau, February 2008, Simon Kuper, Head count belies vision of ‘Eurabia’, Financial Times, 19 August 2007, Doug Saunders, The 'Eurabia' myth deserves a debunking , The Globe and Mail, 20 September 2008, Islam and demography: A waxing crescent, The Economist, 27 January 2011

- Albanian census 2011 Archived 14 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Studie: Acht Prozent der Bevölkerung sind Muslime". derStandard.at. 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Moslims in België per gewest, provincie en gemeentev". Npdata.be. 18 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "5 facts about the Muslim population in Europe". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Sarajevo, juni 2016. CENSUS OF POPULATION, HOUSEHOLDS AND DWELLINGS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, 2013 FINAL RESULTS (PDF). BHAS. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- "Население по местоживеене, възраст и вероизповедание" (in Bulgarian). NSI. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "Hungarian census 2011" (PDF).

- "Populations by religious organizations 1998-2013". Reykjavík: Statistics Iceland.

- "Irish census religion 2016" (PDF).

- More Orthodox Christians than Muslims in Italy

- "Kosovo". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). Monstat. pp. 14, 15. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "Een op de zes bezoekt regelmatig kerk of moskee" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics, Netherlands. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- State Statistical Office, North Macedonia (2002). "Census of Population" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Demiri, Mariglen (2019). "Country Snapshot North Macedonia". Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. 39 (5): 21–23 – via Clarivate Web of Science Core Collection, EBSCO, Google Scholar, ATLA Religion Data base.

- Brunborg & Østby (16 December 2011). "Antall muslimer i Norge". Oslo: SSB. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- (PDF) http://observatorio.hispanomuslim.es/estademograf.pdf. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Sweden (Report)". 2009 Report on International Religious Freedom. U.S. Department of State. October 26, 2009. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "2012 Report on International Religious Freedom - Ukraine". United States Department of State. 20 May 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche (11 April 2018). "'Islam shouldn't culturally shape Germany' - Alexander Dobrindt claims | DW | 11.04.2018". DW.COM. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

Muslims from immigrant families maintain a strong religious commitment which continues across generations. Sixty-four percent of Muslims living in the UK describe themselves as highly religious. The share of devout Muslims stands at 42 percent in Austria, 39 percent in Germany, 33 percent in France and 26 percent in Switzerland.

- "US State Department, International Religious Freedom Report 2006, Belgium". State.gov. 2 October 2005. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- CBS. "Religie aan het begin van de 21ste eeuw". www.cbs.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-04-16.

- Michael Cosgrove, How does France count its Muslim population? Archived 2017-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, Le Figaro, April 2011.

- Eade, John (1996). "Nationalism, Community, and the Islamization of Space in London". In Metcalf, Barbara Daly (ed.). Making Muslim Space in North America and Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520204042. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

As one of the few mosques in Britain permitted to broadcast calls to prayer (azan), the mosque soon found itself at the center of a public debate about "noise pollution" when local non-Muslim residents began to protest.

- "Most Western Europeans favor restrictions on Muslim women's religious clothing | Pew Research Center". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- "Die Zwangsjacke namens Burka". baz.ch/. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- Chesler, Phyllis (2010-03-01). "Worldwide Trends in Honor Killings". Middle East Quarterly.

- Koopmans, Ruud (March 2014). Religious fundamentalism and out-group hostility among Muslims and Christians in Western Europe (PDF). WZB Berlin Social Science Center. pp. 7, 11, 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2015.

- "Islamic fundamentalism is widely spread". Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. December 9, 2013.

- Hekmatpour, Peyman; Burns, Thomas J. (2019). "Perception of Western governments' hostility to Islam among European Muslims before and after ISIS: the important roles of residential segregation and education". The British Journal of Sociology. n/a (n/a): 2133–2165. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12673. ISSN 1468-4446. PMID 31004347.

- "El coordinador antiterrorista de la UE: "Lo de Barcelona volverá a pasar, hay 50.000 radicales en Europa"". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- "Qui sont les 15 000 personnes "suivies pour radicalisation" ?". Le Monde.fr (in French). Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- Gabriella Swerling, Sean O’Neill, Fiona Hamilton, Fariha Karim (2017-05-27). "Huge scale of terror threat revealed: UK home to 23,000 jihadists". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- Online, FOCUS. "Gewaltbereite Islamisten: Erstmals mehr als 10.000 Salafisten in Deutschland". FOCUS Online (in German). Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- "European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism — 6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019.

- European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (2006): Muslims in the European Union. Discrimination and Islamophobia Retrieved September 25, 2012

- "Jaarrapport Integratie 2005 - SCP Summary". www.scp.nl (in Dutch). pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2018-09-15.

- "Postawy wobec Islamu i Muzułmanów" (PDF). Michał Feliksiak (in Polish). CBOS. March 2015.

- "What Do Europeans Think About Muslim Immigration?". Chatham House. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

With the exception of Poland, these countries have either been at the centre of the refugee crisis or experienced terrorist attacks in recent years.

- Lipkowski, Clara; (Grafik), Markus C. Schulte von Drach (2018-11-07). "Die Deutschen werden immer intoleranter". sueddeutsche.de (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- "Muslime auf dem Arbeitsmarkt | WZB". www.wzb.eu. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

Bibliography

- AlSayyad, Nezar; Castells, Manuel, eds. (2002). Muslim Europe Or Euro-Islam: Politics, Culture, and Citizenship in the Age of Globalization. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, co-published with the Center for Middle Eastern Studies (University of California, Berkeley). ISBN 978-0-7391-0338-8. LCCN 2001050240.

- Allen, Chris; Amiraux, Valerie; Choudhury, Tufyal; Godard, Bernard; Karich, Imane; Rigoni, Isabelle; Roy, Olivier; Silvestri, Sara (November 2007). Amghar, Samir; Boubekeur, Amel; Emerson, Michael (eds.). European Islam: Challenges for Society and Public Policy (PDF). Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies. ISBN 978-92-9079-710-4. S2CID 152484262. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Archick, Kristin; Belkin, Paul; Blanchard, Christopher M.; Ek, Carl; Mix, Derek E. (7 September 2011). "Muslims in Europe: Promoting Integration and Countering Extremism" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: CRS Report for Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Bougarel, Xavier (2012) [2007]. "Bosnian Islam as 'European Islam': Limits and Shifts of A Concept". In al-Azmeh, Aziz; Fokas, Effie (eds.). Islam in Europe: Diversity, Identity, and Influence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–124. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511809309.007. ISBN 9780511809309. S2CID 91182456.

- Cesari, Jocelyne, ed. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of European Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199607976.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-960797-6. LCCN 2014936672. S2CID 153038977.

- Cesari, Jocelyne (2012) [2007]. "Muslim Identities in Europe: The Snare of Exceptionalism". In al-Azmeh, Aziz; Fokas, Effie (eds.). Islam in Europe: Diversity, Identity, and Influence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–67. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511809309.005. ISBN 9780511809309. S2CID 153719589.

- Cesari, Jocelyne (January 2012). Brunner, Rainer (ed.). "Securitization of Islam in Europe". Die Welt des Islams. Leiden: Brill Publishers. 52 (3/4): 430–449. doi:10.1163/15700607-201200A8. ISSN 1570-0607. JSTOR 41722006. S2CID 143814967.

- Cesari, Jocelyne (January–June 2002). "Introduction - "L'Islam en Europe: L'Incorporation d'Une Religion"". Cahiers d'Études sur la Méditerranée Orientale et le monde Turco-Iranien (in French). Paris: Éditions de Boccard. 33: 7–20. doi:10.3406/CEMOT.2002.1623. S2CID 165345374. Retrieved 21 January 2021 – via Persée.fr.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Grim, Brian J.; Karim, Mehtab S. (January 2011). "The Future of the Global Muslim Population: Projections for 2010-2030" (PDF). The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. LCCN 2011505325. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Hashas, Mohammed (2018). The Idea of European Islam: Religion, Ethics, Politics and Perpetual Modernity. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315106397. ISBN 9780367509743. S2CID 158337114.

- Hourani, Albert; Ruthven, Malise (2010) [1991]. A History of the Arab Peoples (Updated ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-674-39565-7.

- Karić, Enes (2002). "Is 'Euro-Islam' a Myth, Challenge, or a Real Opportunity for Muslims and Europe?". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. London: Taylor & Francis. 22 (2): 435–442. doi:10.1080/1360200022000027375. ISSN 1360-2004.

- Merdjanova, Ina (30 April 2008). "Euro-Islam v. "Eurabia": Defining the Muslim Presence in Europe". www.wilsoncenter.org. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Nielsen, Jørgen S. (1999). Towards a European Islam. Migration, Minorities, and Citizenship. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230379626. ISBN 978-0-333-72374-6.

- Nielsen, Jørgen S. (2012) [2007]. "The Question of Euro-Islam: Restriction or Opportunity?". In al-Azmeh, Aziz; Fokas, Effie (eds.). Islam in Europe: Diversity, Identity, and Influence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–48. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511809309.004. ISBN 9780511809309. S2CID 143052880.

- Tibi, Bassam (2010). "Euro-Islam: An Alternative to Islamization and Ethnicity of Fear". In Baran, Zeyno (ed.). The Other Muslims: Moderate and Secular. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 157–174. doi:10.1057/9780230106031_10. ISBN 978-0-230-62188-6. S2CID 148008368.

Further reading

- Ghodsee, Kristen (2009). Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, Ethnicity and the Transformation of Islam in Postsocialist Bulgaria. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13955-5.

- König, Daniel G., Arabic-Islamic Views of the Latin West. Tracing the Emergence of Medieval Europe, Oxford, OUP, 2015.

- Hamza, Gabor, Zur Rolle des Islam in der Geschichte des ungarischen Rechts. Revista Europea de Historia de las Ideas Políticas y de las Instituciones Públicas (REHIPIP) Número 3 - Junio 2012 1-11.pp. http://www.eumed.net/rev/rehipip/03/gh.pdf

- Halbach, Uwe. "Islam in the North Caucasus". pp. 93–110.

External links

- For Muslim Minorities, it is Possible to Endorse Political Liberalism, But This is not Enough

- BBC News: Muslims in Europe

- Khabrein.info: Barroso: Islam is part of Europe

- Euro-Islam Website Coordinator Jocelyne Cesari, Harvard University and CNRS-GSRL, Paris

- Asabiyya: Re-Interpreting Value Change in Globalized Societies

- Why Europe has to offer a better deal towards its Muslim communities. A quantitative analysis of open international data

- Köchler, Hans, Muslim-Christian Ties in Europe: Past, Present and Future, 1996

- "Islam in Europe: A Resource Guide". USA: New York Public Library. 2011.

._Bairatdser_(Enseigne)._Ousta_(_Caporal).jpg.webp)