Italian War of 1494–1498

The First Italian War, sometimes referred to as the Italian War of 1494 or Charles VIII's Italian War, was the opening phase of the Italian Wars. The war pitted Charles VIII of France, who had initial Milanese aid, against the Holy Roman Empire, Spain and an alliance of Italian powers led by Pope Alexander VI, known as the League of Venice.

| First Italian War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian Wars | |||||||

Italy in 1494 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

1494: 1495: League of Venice | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 13,000 men[1] | Unknown | ||||||

Prelude

Pope Innocent VIII, in conflict with King Ferdinand I of Naples over Ferdinand's refusal to pay feudal dues to the papacy, excommunicated and deposed Ferdinand by a bull of 11 September 1489. Innocent then offered the Kingdom of Naples to Charles VIII of France, who had a remote claim to its throne because his grandfather, Charles VII, King of France, had married Marie of Anjou[2] of the Angevin dynasty, the ruling family of Naples until 1442. Innocent later settled his quarrel with Ferdinand and revoked the bans before dying in 1492, but the offer to Charles remained an apple of discord in Italian politics. Ferdinand died on 25 January 1494 and was succeeded by his son Alfonso II.[3]

A third claimant to the Neapolitan throne was René II, Duke of Lorraine. He was the oldest son of Yolande, Duchess of Lorraine (died 1483), the only surviving child of René of Anjou (died 1480), the last effective Angevin King of Naples until 1442. In 1488 the Neapolitans had already offered the crown of Naples to René II, who set an expedition to gain possession of the realm, but he was then halted Charles VIII of France, who intended to claim Naples himself. Charles VIII was arguing that his grandmother Marie of Anjou, the sister of René of Anjou, had a closer connection than Rene II's mother Yolande, the daughter of René of Anjou, and therefore he came first in the Angevin line of Neapolitan succession.

French invasion

In October 1494, Ludovico Sforza, who had long controlled the Duchy of Milan, finally procured the ducal title after providing a hitherto unheard-of dowry to his niece, who was marrying the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian. He was immediately challenged by Alfonso II, who also had a claim on Milan. Ludovico decided to remove this threat by inciting Charles to take up Innocent's offer. Charles was also being encouraged by his favorite, Étienne de Vesc, as well as by Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, the future Pope Julius II, who hoped to settle a score with the incumbent Pope, Alexander VI.

Charles VIII gathered a large army of 25,000 men, including 8,000 Swiss mercenaries and the first siege train to include artillery, and invaded the Italian peninsula.[1] He was aided by Louis d'Orleans' victory over Neapolitan forces at the Battle of Rapallo which allowed Charles to march his army through the Republic of Genoa.[4] On 19 October, a contingent of Charles' army besieged the fortress of Mordano. After refusing to surrender, the fortress was bombarded, taken by French-Milanese forces, and the surviving inhabitants massacred.[5]

The arrival of Charles's army outside Florence in mid-November 1494 created fears of rape and pillage.[6] The Florentines were led to exile Piero de' Medici and to establish a republican government. Bernardo Rucellai and other members of the Florentine oligarchy then acted as ambassadors to negotiate a peaceful accord with Charles.

The French finally reached the city of Naples in February 1495, capturing it without a siege or a pitched battle.[7]

League of Venice

The speed of the French advance, together with the brutality of their sack of Mordano, left the other states of Italy in shock. Ludovico Sforza, realizing that Charles had a claim to Milan as well as Naples, and would probably not be satisfied by the annexation of Naples alone, turned to Pope Alexander VI, who was embroiled in a power game of his own with France and various Italian states over his attempts to secure secular fiefdoms for his children. The Pope formed an alliance of several opponents of French hegemony in Italy: himself; Ferdinand of Aragon, who was also King of Sicily; the Emperor Maximilian I; Ludovico in Milan; and the Republic of Venice. (Venice's ostensible purpose in joining the League was to oppose the Ottoman Empire, while its actual objective was French expulsion from Italy.) This alliance was known as the Holy League of 1495, or as the League of Venice, and was proclaimed on 31 March 1495.[8] England joined the League in 1496.[9]

The League gathered an army under the condottiero Francesco II Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua. Including most of the city-states of northern Italy, the League of Venice threatened to shut off King Charles's land route by which to return to France. Charles VIII, not wanting to be trapped in Naples, marched north to Lombardy on 20 May 1495,[7] leaving Gilbert, Count of Montpensier, in Naples as his viceroy, with a substantial garrison.[7] After Ferdinand of Aragon had recovered Naples, with the help of his Spanish relatives with whom he had sought asylum in Sicily, the army of the League followed Charles's retreat northwards through Rome, which had been abandoned to the French by Pope Alexander VI on 27 May 1495.[10]

Charles and the French met the army of the League in the Battle of Fornovo, 30 km (19 miles) southwest of the city of Parma, on 6 July 1495.[11] When the battle was over, both sides claimed victory. Despite their numerical superiority in the battle, the League army took twice as many casualties as the French.[12] But the French had won their battle, fighting off superior numbers and proceeding on their march.[lower-alpha 1][14] After the battle, Charles successfully marched his army across the territories of his enemies on his way back to France.[12] The army of the League could not stop him, but he lost nearly all of the spoils from his campaign in Italy.[12] Charles VIII died in April 1498, before he could regroup his forces and return to Italy.[15]

Consequences

An important consequence of the League of Venice was the political marriage arranged by Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor for the son he had with Mary of Burgundy: Philip the Handsome married Joanna the Mad (daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile) to reinforce the anti-French alliance between Austria and Spain. The son of Philip and Joanna would become Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, succeeding Maximilian and controlling a Habsburg empire which included Castile, Aragon, Austria, and the Burgundian Netherlands, thus encircling France.[16]

The League was the first of its kind; there was no medieval precedent for such divergent European states uniting against a common enemy, although many such alliances would be forged in the future.[9]

Syphilis outbreak

During this war an outbreak of syphilis occurred among the French troops. This outbreak was the first widely documented outbreak of the disease in human history, and eventually led to the Columbian theory of the origin of syphilis.[17]

Gallery

French troops and artillery entering Naples in 1495.

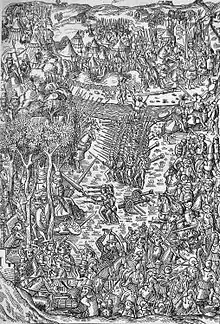

French troops and artillery entering Naples in 1495. Battle of Fornovo, 6 July 1495.

Battle of Fornovo, 6 July 1495.

Notes

- "Florentine historian Francesco Guicciardini, in his History of Italy, states that “universal opinion awarded the palm of victory to the French."[13]"Most sources, both the rewriting of Italian and French, state clearly that the French won at Fornovo, a triumph celebrated in a rare engraving of the battle made shortly after the event by an anonymous French artist. The conclusion of French victory is based on two factors: the Italians did not stop the northward march of the French, and the French sustained far fewer losses."[14]

References

- Ritchie, R. Historical Atlas of the Renaissance. p. 64.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 8.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 12.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 19.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 19-20.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 22.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 28.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 27, 29.

- Anderson, M. S. (1993). The Rise of Modern Diplomacy 1450–1919. London: Longman. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-582-21232-9.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 29.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 30.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 31.

- Nelson & Zeckhauser 2008, p. 168.

- Nelson & Zeckhauser 2008, p. 168-169.

- Mallett & Shaw 2012, p. 38.

- Farhi, David; Dupin, Nicholas (September–October 2010). "Origins of syphilis and management in the immunocompetent patient: facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology. 28: 5. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.011. PMID 20797514.

Bibliography

- Mallett, Michael; Shaw, Christine (2012). The Italian Wars: 1494–1559. Pearson Education Limited.

- Pastor, Ludwig von (1902). The History of the Popes, from the close of the Middle Ages, third edition, Volume V Saint Louis: B. Herder 1902.

- Nelson, Jonathan K.; Zeckhauser, Richard J. (2008). The Patron's Payoff: Conspicuous Commissions in Italian Renaissance Art. Princeton University Press.

Most sources, both the rewriting of Italian and French, state clearly that the French won at Fornovo, a triumph celebrated in a rare engraving of the battle made shortly after the event by an anonymous French artist. The conclusion of French victory is based on two factors: the Italians did not stop the northward march of the French, and the French sustained far fewer losses.