Italian ironclad Francesco Morosini

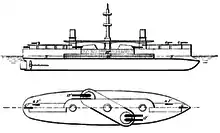

Francesco Morosini was an ironclad battleship built in the 1880s and 1890s for the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy). The ship, named for Francesco Morosini, the 17th-century Doge of Venice, was the second of three ships in the Ruggiero di Lauria class, along with Ruggiero di Lauria and Andrea Doria. She was armed with a main battery of four 17-inch (432 mm) guns, was protected with 17.75-inch (451 mm) thick belt armor, and was capable of a top speed of 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph).

.jpg.webp) Francesco Morosini underway | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Francesco Morosini |

| Namesake: | Francesco Morosini |

| Operator: | Regia Marina |

| Builder: | Venice Navy Yard |

| Laid down: | 4 December 1881 |

| Launched: | 30 July 1885 |

| Completed: | 21 August 1889 |

| Stricken: | August 1909 |

| Fate: | Sunk as target, 15 September 1909 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Ruggiero di Lauria-class ironclad battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 105.9 m (347 ft 5 in) length overall |

| Beam: | 19.84 m (65 ft 1 in) |

| Draft: | 8.29 m (27 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: | 2-shafts, 2 compound steam engines |

| Speed: | 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Endurance: | 2,800 nmi (5,186 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 507–509 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

The ship's construction period was very lengthy, beginning in August 1881 and completing in February 1888. She was quickly rendered obsolescent by the new pre-dreadnought battleships being laid down, and as a result, her career was limited. She spent her career alternating between the Active and Reserve Squadrons, where she took part in training exercises each year with the rest of the fleet. The ship was stricken from the naval register in August 1909; the following month, she was expended as a target ship for experiments with torpedoes.

Design

Francesco Morosini was 105.9 meters (347 ft 5 in) long overall and had a beam of 19.84 m (65 ft 1 in) and an average draft of 8.37 m (27 ft 6 in). She displaced 9,886 long tons (10,045 t) normally and up to 11,145 long tons (11,324 t) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of a pair of compound steam engines each driving a single screw propeller, with steam supplied by eight coal-fired, oval boilers. Her engines produced a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) at 10,000 indicated horsepower (7,500 kW). She could steam for 2,800 nautical miles (5,200 km; 3,200 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). She had a crew of 507–509 officers and men.[1]

Francesco Morosini was armed with a main battery of four 17 in (432 mm) 27-caliber guns, mounted in two pairs en echelon in a central barbette. She carried a secondary battery of two 6-inch (152 mm) 32-cal. guns, one at the bow and the other at the stern, and four 4.7 in (119 mm) 32-cal. guns. As was customary for capital ships of the period, she carried five 14 in (356 mm) torpedo tubes submerged in the hull.[1]

She was protected by steel armor; her armored belt was 17.75 in (451 mm) thick, and her armored deck was 3 in (76 mm) thick. Her conning tower was armored with 9.8 in (249 mm) of steel plate, and the barbette had 14.2 in (361 mm) thick sides.[1]

Service history

Construction – 1895

Francesco Morosini was under construction for nearly eight years. She was laid down at the Venetian Arsenal on 4 December 1881 and launched on 30 July 1885. She was not completed for another four years, her construction finally being finished on 21 August 1889. Because of the rapid pace of naval technological development in the late 19th century, her lengthy construction period meant that she was an obsolete design by the time she entered service.[1] The year she entered service, the British began building the Royal Sovereign class; these ships marked a significant advance over previous types of capital ships and set the standard for future vessels, which became known as pre-dreadnought battleships. In addition, technological progress, particularly in armor production techniques—first Harvey armor and then Krupp armor—rapidly rendered older vessels like Francesco Morosini obsolete.[2]

Francesco Morosini took part in the annual fleet maneuvers of 1894 in 2nd Division of the Active Squadron, along with the protected cruiser Ettore Fieramosca, the torpedo cruiser Tripoli, and four torpedo boats.[3] She remained in the 2nd Division, which now included the protected cruiser Etruria and the torpedo cruisers Euridice and Calatafimi, in 1895. The squadron was based at La Spezia at the time.[4] In 1896, she cruised off Crete as the flagship of the 2nd Division, under Rear Admiral E. Gaulterio.[5] During that year's summer maneuvers, held in July 1896, Francesco Morosini continued as Gaulterio's flagship; the 2nd Division also included her sister Andrea Doria and the protected cruiser Giovanni Bausan. The 1st and 2nd Divisions of the Active Squadron were tasked with defending against a hostile fleet, simulated by older ships in reserve.[6]

1897–1909

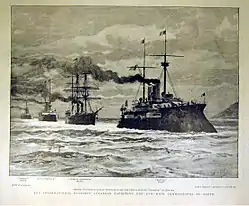

Francesco Morosini deployed to Crete to served in the International Squadron, a multinational force made up of ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, French Navy, Imperial German Navy, Regia Marina, Imperial Russian Navy, and Royal Navy that intervened in the 1897-1898 Greek uprising on Crete against rule by the Ottoman Empire. She took part in the squadron's final operations when, as flagship the Italian division of the International Squadron, she departed Crete along with the British battleship HMS Revenge (flagship of the commander of British forces in the squadron, Rear-Admiral Gerard Noel) and the Russian armored cruiser Gerzog Edinburgski (flagship of the commander of the squadron's Russian forces, Rear Admiral Nikolai Skrydlov) in steaming to Milos with the French protected cruiser Bugeaud, flagship of the International Squadron's overall commander, Rear Admiral Édouard Pottier. At Milos, they rendezvoused with Prince George of Greece and Denmark aboard his yacht. After Prince George boarded Bugeaud on 20 December, Francesco Morosini, Revenge, and Gerzog Edinburgski escorted Bugeaud to Crete, where Prince George disembarked on 21 December 1898 to take office as the High Commissioner of an autonomous Cretan State under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire, bringing the Cretan uprising to an end.[7]

In 1898, Francesco Morosini was transferred to the Reserve Squadron, along with Ruggiero di Lauria and the ironclad Lepanto and five cruisers.[8] The In 1899, Francesco Morosini and her two sisters returned to the Active Squadron, which was kept in service for eight months of the year, with the remainder spent with reduced crews. The squadron also included the ironclads Re Umberto, Sicilia, and Lepanto.[9] In 1900, Francesco Morosini and her sisters were significantly modified and received a large number of small guns for defense against torpedo boats. These included a pair of 75 mm (3 in) guns, ten 57 mm (2.2 in) 40-caliber guns, twelve 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, five 37 mm revolver cannon, and two machine guns.[1]

In 1905, Francesco Morosini and her two sisters were joined in the Reserve Squadron by the three Re Umberto-class ironclads and Enrico Dandolo, three cruisers, and sixteen torpedo boats. This squadron only entered active service for two months of the year for training maneuvers, and the rest of the year was spent with reduced crews.[10] In 1908, the Italian Navy decided to discard Francesco Morosini and her sister Ruggiero di Lauria.[11] She was formally stricken from the naval register in August 1909, and was thereafter used as a target ship for a torpedo experiment. On 15 September, she was sunk at La Spezia; the experiment was conducted to test the effect of a torpedo hit in order to develop more a more effective hull design. The explosion tore a 50-square-meter (540 sq ft) hole in the hull, causing her to list severely and sink on her side. Her wreck was later scrapped.[12][13]

Notes

- Gardiner, p. 342

- Sondhaus, pp. 107–108, 111

- "Naval and Military Notes – Italy", p. 564

- Garbett 1895, pp. 89–90

- Robinson, pp. 184–185

- "The Italian Manoeuvres", pp. 131–132

- Clowes, pp. 444–448

- Garbett, p. 200

- Brassey (1899), p. 72

- Brassey (1905), p. 45

- Brassey (1908), p. 31

- "Torpedo Experiments Against the 'Francesco Morosini'", pp. 304–305

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 256

References

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1899). The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.).

- Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1905). "Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 40–57. OCLC 937691500.

- Brassey, Thomas A., ed. (1907). The Naval Annual (Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.).

- Clowes, Sir William Laird. The Royal Navy: A History From the Earliest Times to the Death of Queen Victoria, Volume Seven. London: Chatham Publishing, 1997. ISBN 1-86176-016-7.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1898). "Naval Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XLII: 199–204. OCLC 8007941.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1895). "Naval and Military Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XXXIX: 81–111. OCLC 8007941.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- "Naval and Military Notes – Italy". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher. XXXVIII: 564–565. 1894. OCLC 8007941.

- Robinson, Charles N., ed. (1897). The Navy and Army Illustrated (London: Hudson & Kearns) III (32).

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2014). Navies of Europe. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-86978-8.

- "The Italian Manoeuvres". Notes on Naval Progress. Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence: 131–140. 1897.

- "Torpedo Experiments Against the "Francesco Morosini"". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. Washington, DC: R. Beresford, Printer. XXII (1): 304–305. 1910.