Cretan State

The Cretan State (Greek: Κρητική Πολιτεία, romanized: Kritiki Politeia; Ottoman Turkish: كريد دولتى, romanized: Girid Devleti) was established in 1898, following the intervention by the Great Powers (United Kingdom, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Russia) on the island of Crete. In 1897, an insurrection on Crete led the Ottoman Empire to declare war on Greece, which led United Kingdom, France, Italy and Russia to intervene on the grounds that the Ottoman Empire could no longer maintain control. It was the prelude to the island's final annexation to the Kingdom of Greece, which occurred de facto in 1908 and de jure in 1913.

Cretan State | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898–1913 | |||||||||

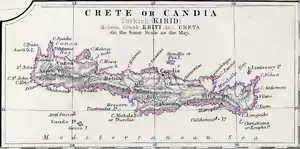

Map of Crete (1861) | |||||||||

| Status | Autonomous state of the Ottoman Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Chania | ||||||||

| Largest city | Heraklion | ||||||||

| Common languages | Greek (official), Ottoman Turkish (recognised) | ||||||||

| Religion | Greek Orthodox (prevailing religion), Sunni Islam (recognised), Judaism | ||||||||

| High Commissioner | |||||||||

• 1898–1906 | Prince George | ||||||||

• 1906–1911 | Alexandros Zaimis | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1910 | Eleftherios Venizelos | ||||||||

| Legislature | Assembly | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 9 December 1898 | |||||||||

| 23 March 1905 | |||||||||

• Unilateral union with Greece | 7 October 1908[1] | ||||||||

| 30 May 1913 | |||||||||

| 1 December 1913 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1907 | 8,336 km2 (3,219 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1907 | 310,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Cretan drachma | ||||||||

| |||||||||

History

Background

The island of Crete, an Ottoman possession since the end of the Cretan War, was inhabited by a mostly Greek-speaking population, whose majority was Christian. During and after the Greek War of Independence, the Christians of the island rebelled several times against external Ottoman rule, pursuing union with Greece. These were brutally subdued, but secured some concessions from the Ottoman government under the pressure of European public opinion. In 1878, the Pact of Halepa established the island as an autonomous state under Ottoman suzerainty, until the Ottomans reneged on that agreement in 1889.

The collapse of the Pact heightened tensions in the island, leading to another rebellion in 1895, which greatly expanded in 1896–1897 to cover most of the island. Six Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, France, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, the Russian Empire, and the United Kingdom) sent warships to Crete in February 1897, and their naval forces combined to form an "International Squadron" charged with intervening to bring fighting on Crete to a halt.[2] In Greece, nationalist secret societies and a fervently irredentist public opinion forced the Greek government to send military forces to the island. Although the International Squadron quickly halted their activities,[2] the presence of Greek forces on Crete provoked a war with the Ottoman Empire. Although most of Crete came under the control of Cretan insurgent and Greek forces, the unprepared Greek Army was crushed by the Ottomans, who occupied Thessaly. The war was ended by the intervention of the Great Powers (the United Kingdom, France, Italy and Russia), who forced the Greek contingent to withdraw from Crete and the Ottoman Army to stop its advance. In the Treaty of Constantinople the Ottoman Government promised to implement the provisions of the Halepa Pact.

Establishment of the Cretan State

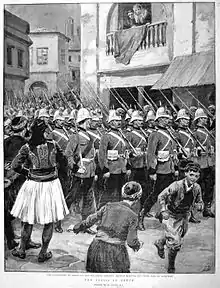

In February 1897, the Great Powers decided to restore order by governing the island temporarily through an "Admirals Council" consisting of admirals from the six powers making up the International Squadron. Through naval bombardments of Cretan insurgent forces, by placing sailors and marines ashore to occupy key cities, and by establishing a blockade of Crete and key ports in Greece, the International Squadron brought organized fighting on Crete to an end by the end of March 1897, although the insurrection continued.[3] Soldiers from the armies of five of the powers (Germany declined to send any) arrived to occupy key Cretan cities in late March and April 1897.[4] Thereafter, the Admirals Council focused on a negotiated settlement that would bring the insurrection to an end without bringing Ottoman governance of Crete to an end, but this proved impossible. They then decided that Crete would become an autonomous state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. Germany strongly opposed this idea and withdrew from Crete and the International Squadron in November 1897 and Austria-Hungary followed in March 1898, but the remaining four powers carried on with their plans.[5]

On 6 September 1898 (25 August 1898 according to the Julian calendar then in use on Crete, which was 12 days behind the modern Gregorian calendar during the 19th century), a Cretan Muslim mob massacred hundreds of Cretan Greeks and murdered the British vice-consul, his family, and 14 British soldiers and sailors, in the city of Candia (modern Heraklion). As a result, the International Squadron and the occupying forces ashore expelled all Ottoman forces from Crete in November 1898.[6] The autonomous Cretan State, under Ottoman suzerainty, garrisoned by an international military force, and with its high commissioner provided by Greece, was founded when Prince George of Greece and Denmark arrived to take office as the first high commissioner (Greek: Ὕπατος Ἁρμοστής, Hýpatos Harmostēs), effectively detaching Crete from the Ottoman Empire, on 21 December 1898 (9 December according to the Julian calendar).[7][8] The Admirals Council was dissolved on 26 December 1898.[9]

The National Bank of Greece established a bank, the Bank of Crete, which had a 40-year monopoly on note issuance. The Cretan State also established a paramilitary force, the Cretan Gendarmerie, modeled on the Italian Carabinieri, to maintain public order. The Cretan Gendarmerie incorporated the four small gendarmerie units the four remaining occupying powers had created before the arrival of Prince George.

Internal turmoil – the Therisos Revolt

On 13 December 1898, Prince George of Greece and Denmark arrived as high commissioner for a three-year tenure. On 27 April 1899, an Executive Committee was created, in which a young, Athens-trained lawyer from Chania, Eleftherios Venizelos, participated as minister of justice. By 1900, Venizelos and Prince George had developed differences over domestic policies, as well as the issue of Enosis, the union with Greece.

Venizelos resigned in early 1901, and for the next three years, he and his supporters waged a bitter political struggle with the Prince's faction, leading to a political and administrative deadlock on the island. Eventually, in March 1905, Venizelos and his supporters gathered in the village of Therisos, in the hills near Chania, constituted a "Revolutionary Assembly", demanded political reforms and declared the "political union of Crete with Greece as a single free constitutional state" in a manifesto delivered to the consuls of the Great Powers. The Cretan Gendarmerie remained loyal to the Prince, but numerous deputies joined the revolt, and despite the Powers' declaration of military law on 18 July, their military forces did not move against the rebels.

On 15 August, the Cretan Assembly voted for the proposals of Venizelos, and the Great Powers brokered an agreement, whereby Prince George would resign and a new constitution created. In the 1906 elections the pro-Prince parties took 38,127 votes while pro-Venizelos parties took 33,279 votes, but in September 1906 Prince George was replaced by former Greek prime minister Alexandros Zaimis and left the island. In addition, Greek officers came to replace the Italians in the organization of the Gendarmerie, and the withdrawal of the foreign troops began, leaving Crete de facto under Greek control.

Union with Greece

A Constitution was promulgated in February 1907, but in 1908, taking advantage of domestic turmoil in Turkey as well as the timing of Zaimis' vacation away from the island, the Cretan deputies declared unilateral union with Greece.[10] The flag of the Cretan State was replaced by the Greek flag, all public servants took an oath to King George I of Greece, and the Greek constitution and laws were enacted on the island. This act was not recognized internationally, including by Greece, where Eleftherios Venizelos was elected prime minister in 1910. In May 1912, the Cretan deputies travelled to Athens and tried to enter the Greek Parliament, but were forcibly prevented from doing so by the police.

Upon the outbreak of the First Balkan War, Greece finally recognized the union and sent Stephanos Dragoumis as the island's governor-general. The Great Powers tacitly recognized the fait accompli by the act of lowering their flags from the Souda fortress on 14 February 1913, and by the Treaty of London in May 1913, Sultan Mehmed V relinquished his formal rights to the island.

On 1 December, the formal ceremony of union took place: the Greek flag was raised at the Firka Fortress in Chania, with Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine I in attendance. The Muslim minority of Crete initially remained on the island but was later relocated to Turkey under the general population exchange agreed to in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne between Turkey and Greece.

Population

The total population in 1911 was 336,151: 307,812 Christians, 27,852 Muslims and 487 Jews.[11]

References

Notes

- Anderson, Frank Maloy; Amos Shartle Hershey (1918). "The Cretan Question, 1897–1908". Handbook for the Diplomatic History of Europe, Asia, and Africa 1870–1914. National Board for Historical Service, United States Government Publishing Office.

- McTiernan, pp. 13–14.

- McTiernan, pp. 13–23.

- McTiernan, pp. 20–21.

- McTiernan, p. 28.

- McTiernan, pp. 32–35.

- Kitromilides M. Paschalis (ed) Eleftherios Venizelos: The Trials of Statesmanship, Edinburgh University Press, 2008 p. 68.

- McTiernan, pp. 36–39.

- McTiernan, p. 39.

- Ion, Theodore P., "The Cretan Question," The American Journal of International Law, April, 1910, pp. 276–284

- First encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936, M. Th Houtsma, page 879

Further reading

- Kallivretakis, Leonidas (2006). "A Century of Revolutions: The Cretan Question between European and Near East Politics". In P. Kitromilides (ed.). Eleftherios Venizelos: the trials of statesmanship, A (PDF). 1. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 11–35. ISBN 978-0-74867126-7.

- Λιμαντζάκης Γιώργος, Το Κρητικό Ζήτημα, 1868-1913, από τα πεδία των μαχών στη διεθνή διπλωματία (Τhe Cretan Question, 1868-1913, from the battlefields to international diplomacy), Εθνικό Ίδρυμα Ερευνών και Μελετών «Ελευθέριος Κ. Βενιζέλος», 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - A. Lilly Macrakis (2006). "Venizelos' Early Life and Political Career in Crete, 1864–1910". In P. Kitromilides (ed.). Eleftherios Venizelos: the trials of statesmanship, A. 1. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 27–84. ISBN 978-0-74867126-7.