RMS Lucania

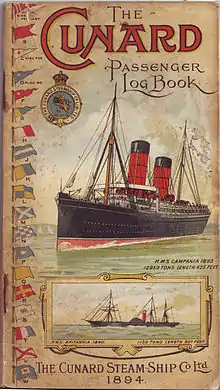

RMS Lucania was a British ocean liner owned by the Cunard Steamship Line Shipping Company, built by Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company of Govan, Scotland, and launched on Thursday, 2 February 1893.

RMS Lucania | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner: | Cunard Line |

| Port of registry: | Liverpool, United Kingdom |

| Builder: | Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company yard in Govan, Scotland |

| Yard number: | 365 |

| Launched: | Thursday, 2 February 1893 |

| Christened: | Sir William Pearce, MP |

| Maiden voyage: | 2 September 1893 |

| Fate: | Scrapped by Thos W Ward after being damaged by a fire at Liverpool on 14 August 1909 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 12,950 gross register tons (GRT) |

| Length: | 622ft (189.6 m) |

| Beam: | 65 ft 3 in (19,9m) |

| Depth: | 41 ft 10 in (13.7m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | Two triple-blade propellers. |

| Speed: |

|

| Capacity: |

|

| Crew: | 424 |

Identical in dimensions and specifications to her sister ship and running mate RMS Campania, RMS Lucania was the joint largest passenger liner afloat when she entered service in 1893. On her second voyage, she won the prestigious Blue Riband from the other Cunarder to become the fastest passenger liner afloat, a title she kept until 1898.

Power plant and construction

Lucania and Campania were partly financed by the Admiralty. The deal was that Cunard would receive money from the Government in return for constructing vessels to admiralty specifications and also on condition that the vessels go on the naval reserve list to serve as armed merchant cruisers when required by the government. The contracts were awarded to the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, which at the time was one of Britain’s biggest producers of warships. Plans were soon drawn up for a large, twin-screw steamer powered by triple expansion engines, and construction began in 1891, just 43 days after Cunards' order.[1]:xli

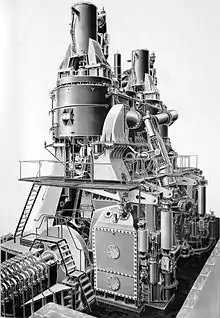

Lucania and Campania had the largest triple-expansion engines ever fitted to a Cunard ship. These engines were also the largest in the world at the time, and still rank today amongst the largest of the type ever constructed. They represent the limits of development for this kind of technology, which was superseded a few years later by turbine technology. In height, the engines were 47 feet, reaching from the double-bottom floor of the engine room almost to the top of the superstructure – over five decks. Each engine had five cylinders. There were two high-pressure cylinders, each measuring 37 in (940 mm) in diameter; one intermediate-pressure cylinder measuring 79 in (2,000 mm) in diameter; and two low-pressure cylinders, each measuring 98 in (2,500 mm) in diameter. They operated with a stroke of 69 in (1,800 mm). Steam was raised from 12 double-ended scotch boilers, each measuring 18 ft (5.5 m) in diameter and having eight furnaces. There was also one single-ended boiler for auxiliary machinery and one, smaller, donkey boiler. Boiler pressure was 165 lb, and enabled the engines to produce 31,000 ihp (23,000 kW), which translated to an average speed of 22 knots (41 km/h), and a record speed of 23 1⁄2 knots.[1]:xli-xlii Normal operating speed for the engines was about 79 rpm.

Each engine was located in a separate watertight engine compartment. In case of a hull breach in that area, only one engine room would then be flooded, and the ship would still have use of the adjacent engine. In addition to this Lucania had 16 transverse watertight compartments, with watertight doors that could be manually closed on command from the telegraph on the bridge. She could remain afloat with any two compartments flooded.[1]:xli

Passenger accommodation

In their day, both ships offered the most luxurious first-class passenger accommodations available. According to maritime historian Basil Greenhill, in his book Merchant Steamships, the interiors of Campania and Lucania represented Victorian opulence at its peak – an expression of a highly confident and prosperous age that would never be quite repeated on any other ship.[2]:39 Greenhill remarked that later vessels' interiors degenerated into "grandiose vulgarity, the classical syntax debased to mere jargon".[2]:40

All the first-class public rooms, and the en-suite staterooms of the upper deck, were generally heavily panelled, in oak, satinwood or mahogany; and thickly carpeted. Velvet curtains hung aside the windows and portholes, while the furniture was richly upholstered in matching design. The predominant style was Art Nouveau, although other styles were also in use, such as "French Renaissance" which was applied to the forward first-class entrance hall, whilst the 1st class smoking room was in "Elizabethan style", comprising heavy oak panels surrounding the first open fireplace ever to be used aboard a passenger liner.

Perhaps the finest room in the vessels was the first class dining saloon, over 10 feet (3.05 m) high and measuring 98 feet (30 m) long by 63 feet (19.2 m) wide. Over the central part of this room was a well that rose through three decks to a skylight. It was done in a style described as "modified Italian style", with a coffered ceiling in white and gold, supported by ionic pillars. The panelled walls were done in Spanish mahogany, inlaid with ivory and richly carved with pilasters and decorations.[1]:xlii-xliii

Wireless history

On 15 June 1901 Lucania became the first Cunard liner to be fitted with a Marconi wireless system. Cunard made a long trial of the installation, making their second installation to the RMS Campania on 21 September.[3]:30–31 Shortly after these installations, the two ships made history by exchanging the first wireless transmitted ice bulletin.

In October 1903, Guglielmo Marconi chose Lucania to carry out further experiments in wireless telegraphy, and was able to stay in contact with radio stations in Nova Scotia and Poldhu.[4]:235 Thus it became possible to transmit news to Lucania for the whole duration of the Atlantic crossing. On 10 October, Lucania made history again by publishing an onboard news-sheet based on information received by wireless telegraphy whilst at sea. The newspaper was called Cunard Daily Bulletin and quickly became a regular and successful publication.[3]:41 [4]:235

Final days

Lucania and Campania served as Cunard's major passenger liners for 14 years, during which time both liners were superseded in speed and size by a succession of four-funnelled German liners, starting with the SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in 1897. The German competition necessitated the construction of replacements for the two Cunarders, which came to fruition in 1907 with the appearance of the RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania. It was soon decided that Lucania was no longer needed, and her last voyage was on 7 July 1909, after which she was laid up at the Huskisson Dock in Liverpool. On the evening of 14 August 1909, she was badly damaged by a fire and partially sank at her berth. Five days later she was sold for scrap and the contents of her interior auctioned.

See also

References

- Warren, Mark (1993). The Cunard Royal Mail Steamers Campania and Lucania. Patrick Stephens Limited. pp. xli. ISBN 1-85260-148-5.

- Greenhill, Basil (1979). Merchant Steamships. London: B.T. Batsford Limited.

- Hancock, H.E. (1950). Wirekess at Sea. Chelmsford: Marconi International Marine Communication Company.

- Kennedy, John (1903). History of Steam Navigation. Liverpool: Charles Birchall Limited.

External links

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Campania |

Blue Riband Eastbound record) 1894 – 1897 |

Succeeded by Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse |

| Blue Riband (Westbound record) 1894 – 1898 | ||