Italian occupation of Majorca

The Italian occupation of Majorca lasted throughout the Spanish Civil War. Italy intervened in the war with the possible intention of annexing the Balearic Islands and Ceuta and creating a client state in Spain.[1] The Italians sought to control the Balearic Islands because of their strategic position, from which they could disrupt lines of communication between France and its North African colonies, and between British Gibraltar and Malta.[2] Italian flags were flown over the island.[3] Italian forces dominated Majorca, with Italians openly manning the airfields at Alcúdia and Palma, as well as Italian warships being based in the harbour of Palma.[4] However some historians -like Gilbeto Oneto and Rosaria Quartararo- expressed a criticism about this supposed Italian plan to annex Majorca.

| Majorca Majorca | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian-occupied territory | |||||||||

| 1936–1939 | |||||||||

_crowned.svg.png.webp) Flag

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms

| |||||||||

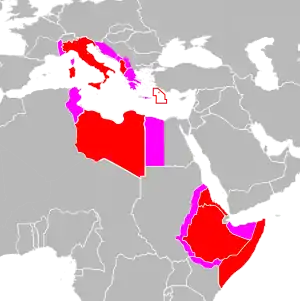

The Balearic Islands during the Spanish Civil War. Majorca is the large central island. Light blue: Italian / Spanish Nationalist-occupied territory. Grey: Spanish Republican-occupied territory. | |||||||||

| Capital | Palma | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Occupation | ||||||||

| Proconsul | |||||||||

• 1936 | Arconovaldo Bonaccorsi | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

• Established | 1936 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1939 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

History

Prior to all-out intervention by Italy, Benito Mussolini authorized "volunteers" to go to Spain, resulting in the seizure of the largest Balearic island of Majorca by a force under Fascist Blackshirt leader Arconovaldo Bonaccorsi (also known as "Count Rossi").[5]

Sent to Majorca to act as Italian proconsul in the Balearics,[5] Bonaccorsi proclaimed that Italy would occupy the island in perpetuity[6] and initiated a brutal reign of terror (as a vengeance for the previous killing by the Republicans of thousands of religious and civilian anticommunists), arranging the murder of 3,000 people accused of being communists, and emptying Majorca's prisons by having all prisoners shot.[5] In the aftermath of the Battle of Majorca, Bonaccorsi renamed the main street of Palma de Majorca Via Roma, and adorned it with statues of Roman eagles.[7] Bonaccorsi was later rewarded by Italy for his activity in Majorca.[8]

Italian forces launched air raids from Majorca against Republican-held cities on mainland Spain.[9] Initially Mussolini only authorized a weak force of Italian bomber aircraft to be based in Majorca in 1936 to avoid antagonizing Britain and France.[10] However the lack of resolve by the British and French to Italy's strategy in the region, encouraged Mussolini to deploy twelve more bombers to be stationed in Majorca, including one aircraft flown by his son, Bruno Mussolini.[11] By January 1938, Mussolini had doubled the number of bombers stationed in the Balearics and increased bomber attacks on shipping headed to support Spanish Republican forces.[12] The buildup of Italian bomber aircraft on the island's airfields and increased Italian air attacks on Republican-held ports and shipping headed to Republican ports was viewed by France as provocative.[13]

After Franco's victory in the civil war, and several days after Italy's conquest in the Balkans of Albania, Mussolini issued an order on April 11 or 12 1939, to withdraw all Italian forces from Spain.[14] Mussolini issued this order in response to Germany's sudden action of invading Czechoslovakia in 1939, in which Mussolini was aggravated by Hitler's swift success and sought to prepare Italy to make similar conquests in Eastern Europe.[15]

Criticism of supposed plan

The existence of a supposed Italian plan to annex Majorca has received harsh critics. Indeed, Gilberto Oneto, an Italian historian, wrote the following about Bonaccorsi and the Italians in Majorca:

The nationalist revolt, suppressed in all of Catalonia, has happened successfully only in the island of Mallorca, but the Republicans are going to occupy it. The Italian government has a strong interest (not just strategic) for the Balearic Islands. Action is needed urgently. Need someone skilled enough, smart, determined and ruthless, and they remember the beefy bolognese squadrista Bonaccorsi. On August 26, 1936 he landed at Palma, calling himself Count Aldo Rossi ("Conde Rossi" or el Conde de Leon y Son Servera for Spanish). Resolutely takes command of the disorganized local nationalist forces, puts together 2.500/3.500 men between soldiers, legionaries of Tercio, volunteers, soldiers of the Guardia Civil and Falange, and deals with strong decision against the Republican forces (6000 to 10,000 men) landed 10 days prior to Manacor, commanded by General Alberto Bayo, a theorist of guerrilla warfare and the future "ideal teacher" of Fidel Castro. With the support of the Italian airforce on September 3 Bonaccorsi defeats the Republicans who begin a disastrous retreat that ended on day 12. After the victory of Manacor Bonaccorsi appoints himself military commander and inspector general of all the troops, creating the "Dragones de la muerte". On 20 September with 500 men he landed in Ibiza, camouflaged. He also takes Formentera and Cabrera. Only Minorca remains in the hands of the Reds, protected by a secret agreement between Italy and England. Bonaccorsi then starts to do the "pacification" of Majorca, "cleaning" the island from Marxists. George Bernanos describes the nearly 3,000 executions of communists done by Bonaccorsi's Dragones de la muerte, but he did not see the early violence (nearly 1,500 nationalists killed only in Majorca) of the Marxists done before the arrival of Bonaccorsi. In reality, the Bonaccorsi murders were only 700 (or 1500, as reported by the Italian consul in the Balearic islands), but this was enough to create huge complaints from France and England (even if in Majorca the civil war deaths were in percentage one tenth of those happened in continental Spain). The pressures were such, that he was forced -by diplomatic missions- to be returned to Italy on December 23, 1936. Additionally, Mussolini did not like the Bonaccorsi boasting that Italy was to remain forever in Majorca.

In Oneto's opinion, the Italians only supported (initially, when Bonaccorsi landed in the island) the possibility of promoting a semi-independent Majorca (under Italian influence) in case of Republican victory in the Spanish civil war. But with Franco's victory, they understood that this project of "partial" independence was impossible.[16]

See also

References

- R. J. B. Bosworth. The Oxford handbook of fascism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009. Pp. 246.

- John J. Mearsheimer. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. W. W. Norton & Company, 2003.

- S. Balfour. Spain and the Great Powers in the Twentieth Century. Routledge, London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: 1999. p. 172.

- LIFE 22 November 1937.

- Moseley, Ray (2000). Mussolini's Shadow: The Double Life of Count Galeazzo Ciano. Yale University Press. p. 27.

- Raanan Rein. Spain and the Mediterranean Since 1898. London, England, UK; Portland, Oregon, USA: FRANK CASS, 1999. Pp. 155.

- Abulafia, David. 2001. The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. p. 604

- Mr. Ray Moseley. Mussolini's Shadow: The Double Life of Count Galeazzo Ciano. Yale University Press, 2000. Pp. 27.

- S. Balfour. Spain and the Great Powers in the Twentieth Century. Routledge, London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: 1999. p. 172.

- Reynolds Mathewson Salerno. Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935-1940. Cornell University, 2002. Pp. 32.

- Reynolds Mathewson Salerno. Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935-1940. Cornell University, 2002. Pp. 32.

- Reynolds Mathewson Salerno. Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935-1940. Cornell University, 2002. Pp. 29.

- Reynolds Mathewson Salerno. Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935-1940. Cornell University, 2002. Pp. 32.

- Robert H. Whealey. Hitler And Spain: The Nazi Role in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Paperback edition. Lexington, Kentucky, USA: University of Kentucky Press, 2005. Pp. 62.

- Robert H. Whealey. Hitler And Spain: The Nazi Role in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Paperback edition. Lexington, Kentucky, USA: University of Kentucky Press, 2005. Pp. 62.

- Canosa, Romano. "Mussolini e Franco. Amici, alleati, rivali: vite parallele di due dittatori - Romano Canosa - Libro - Mondadori - Le scie | IBS". www.ibs.it.