Ethio-Djibouti Railways

The Ethio-Djibouti Railway (French: Chemin de Fer Djibouto-Éthiopien (C.D.E.) is a metre gauge railway in the Horn of Africa that once connected Addis Ababa to the port city of Djibouti. The operating company was also known as the Ethio-Djibouti Railways. The railway was built in 1894–1917 to connect the Ethiopian capital city to French Somaliland. During early operations, it provided landlocked Ethiopia with its only access to the sea. After World War II, the railway progressively fell into a state of disrepair due to competition from road transport.

| Ethio-Djibouti Railways | |

|---|---|

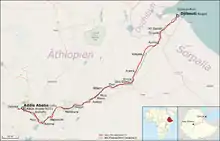

Map of the Ethio-Djibouti Railway line | |

| Overview | |

| Other name(s) | Franco-Ethiopian Railway (1908–1981) |

| Status | Partially operational |

| Termini | Addis Ababa Djibouti |

| Service | |

| System | Heavy rail |

| History | |

| Opened | First commercial service in 1901, completed in 1917 |

| Superseded by | Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 784 km (487 mi) |

| Track gauge | 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) metre gauge |

Ethio-Djibouti Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The railway has been mostly superseded by the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway, an electrified standard gauge railway that was completed in 2017.[1] The metre gauge railway has been abandoned in central Ethiopia and Djibouti. However, a rehabilitated section is still in operation near the Ethiopia-Djibouti border. As of February 2018, a combined passenger and freight service runs two times a week between the Ethiopian city of Dire Dawa and the Djibouti border, stopping at Dewele (passengers) and Guelile (freight).[2] Plans were announced in 2018 to rehabilitate track from Dire Dawa to Mieso.[3]

Overview

The Ethio-Djibouti Railway is a 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge railway built in 1897–1917. The line connected the new Ethiopian capital city of Addis Ababa (1886) to the Port of Djibouti in French Somaliland, providing landlocked Ethiopia with railway access to the sea. The railway is single track and stretched 784 km, of which about 100 km lay in Djibouti.[4]

Railway construction started in 1897, one year after Ethiopia preserved its independence against Italian imperialism at the Battle of Adwa. Prior to the construction of the railway, it took six weeks to travel from the coast to Addis Ababa by camel and mule caravan. The Ethio-Djibouti Railway made the Ethiopian Empire more accessible to the outside world, improving its economic and military competitiveness. Cities grew along the railway line with the expanded opportunities for trade. The railway served as Ethiopia's main transport link until the 1950s, when it began facing competition from road transport.[5]

Originally, the railway was French-dominated and serve as a French exclave in Ethiopia. In 1909, the railway was nationalized in Ethiopia. The role of Ethiopians in railway operation grew over the decades until they occupied most positions after 1959. The railway became a symbol of Ethiopian independence and a source of national pride.[5]

Rolling stock

The railway was initially operated exclusively with steam locomotives. Until 1951, the main supplier of heavy locomotives was the Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works (SLM), which was known for the performance of its steam locomotives in mountainous terrain. In 1954, the main provider of diesel-powered locomotives became Alsthom.

The main locomotives and self-propelled railcars were:

- SLM steam locomotives 1-9 and 21-33 (1898–1950s)

- SLM M-series diesel (1950–1990s)

- Alsthom BB-series diesel (1954–present)

- Soulé diesel-electric railcars (1964–present)

Overnight locomotive-hauled trains consisted of 1st salon sleepers, 2nd class couchettes, and 3rd class coaches. Daytime passenger services were operated by 3rd class diesel railcar at speeds of up to 85 km/h. The first diesel-powered railcar was ordered in 1938 (Fiat "Littorina" series), and only DMUs were ordered after 1950. For political reasons, only the 3rd class coaches and railcars were retained on the railway after 1974.

Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia traveled on an imperial train, which consisted of two locomotives, a baggage car with a diesel generator, four imperial carriages for the emperor and his family (lounge, sleeping compartments, offices, kitchen and restaurant), two 1st class salon-sleeper cars for guests of the Royal family and government officials, and two 2nd passenger cars.

Freight wagons carried 9–30 tonnes until 1987, when new freight wagons were ordered that could carry 30–40 tonnes.

Stations

.jpg.webp)

Since the railway was single-track, most stations along the railway included a passing loop. From 1898 until roughly 1960, there were also water towers for supplying steam locomotives. Most stations also had a small operations building in addition to the passenger station building.

Dedicated railway stations with a single platform and station facilities for travellers were present at only three stations along the railway: Legehar train station, Dire Dawa, and Djibouti City. The Addis Ababa railway station was completed its current form in 1929, the Dire Dawa station in 1910, and the Djibouti City station in 1900. The Dire Dawa station is the main intermediate stop, as most maintenance workshops and other facilities are located there. Only the Dire Dawa railway station remains operational as of 2018.

Specifications

The Ethio-Djibouti Railway was based on French railway standards. The ballast bed for the rails was made by crushed stone, usually 4 centimetres in size. French steelworks supplied almost all of the rails and sleepers from 1898 to 1975, when maintenance of the railway ceased. The 2007–2012 rehabilitation program funded by the European Union set up two factories in Ethiopia, one in Dukem for steel products and one in Dire Dawa for concrete sleepers.

- Gauge: Metre gauge

- Railway total length: 784 km

- Operational length:

- 1902: 311 km (Djibouti-Dire Dawa)

- 1917-2004: 784 km (Djibouti-Addis Ababa)

- 2004-2014: 311 km (Djibouti-Dire Dawa)

- Since 2014: 213 km (Guelile-Dire Dawa)

- Axle load:

- 1898-1947: 8 tonnes

- 1947-2010: 9.5-12.5 tonnes

- 2012-2014: 12.5-17 tonnes

- Since 2014: 16-17 tonnes

- Rail weight:

- 1898-1947: 20–25 kg/m

- 1947-2010: 20-25-30 kg/m

- Since 2012: 30-36-40 kg/m

- Minimum railway curve radius:

- 1898-2014: 200 meters, 150 meters at difficult locations, one curve with 100 meter

- Since 2014: 200 meters

- (ruling) gradient: 1.35% (2.7% with double-locomotive operation in difficult terrain)

- Maximum speed: 90 km/h (passenger trains), 65 km/h (freight trains)

- Operating speed: 45 km/h

- Maximum train load (freight): 300 tonnes (at a speed of 15 km/h at high railway gradients)

- Bridges, viaducts and culverts: 187 viaducts and steel bridges[6]

- Major bridges and viaducts: Chebele viaduct (156 m long), Holhol viaduct (138 m long), Awash River bridge (151 m long, 60 m deep)[6]

- Tunnels: One tunnel through the 'Gol du Harr' northeast of Dire Dawa (170 m long)[6]

History

Origins

The ) was founded in 1894 to build and operate a railway from the port of Djibouti to the Ethiopian capital city of Addis Ababa. The company was founded by Alfred Ilg and headquartered in Paris, France.[7]

Discussion of an Ethiopian railway was initiated by the Swiss engineer Alfred Ilg. He attempted, without success, to interest Emperor Yohannes IV in the construction of a railway to replace the six-week mule trek from central Ethiopia to the French colonial port city. Negotiations began anew when Menelik II acceded to the Ethiopian throne in 1889. On February 11, 1893, Menelik II issued a decree to study the construction of a rail line from the new capital city of Addis Ababa.

In 1894, Ilg and his French associate Léon Chefneux founded the Imperial Railway Company of Ethiopia (French: Compagnie Impériale des Chemins de fer d'Éthiopie[7] or Compagnie Impériale Éthiopienne,[8] with its headquarters in Paris. The company received a royal charter on March 9, 1894, but Menelek resisted putting any of his personal funds into the venture. Instead, the company received a 99-year concession to operate the railway, in return for giving Menelek shares in the company and half of all profits in excess of 3,000,000 francs. Furthermore, the firm was obliged to construct a telegraph line along the route.

Construction (1897–1917)

It took until 1897 before the necessary permission from French authorities was received, by which time significant opposition in Ethiopia had materialized. The emperor himself was irate at the involvement of the French government, which had offered to fund the line,[7] and there were popular demonstrations against it. There was also opposition from the British legation in Addis Ababa, which feared a reduction in traffic to the port of Zeila in British Somaliland. These fears proved well-founded: even half-finished, without links to either Harar or Addis Ababa, the railroad quickly eclipsed the port's former caravan-based trade.[9]

The firm also had difficulty selling its shares in Europe. Robert Le Roux campaigned for the line at municipal chambers of commerce around France,[10] but investor interest was restrained.[7] All in all, the initial stock offering only raised 8,738,000 francs of the 14 million projected, and an additional offering of 25.5 million francs in bonds yielded only 11,665,000 francs. This was far too little to complete the line. Despite the shortfall, construction began in October 1897 from Djibouti, a hitherto minor port city that eventually expanded thanks to the railway.

A crew of Arab and Somali workers,[11] overseen by Europeans, began to press inland with the railway and its associated telegraph. Ethiopians were hired largely as security forces, to prevent the theft of materials on the line. This was also an important source of corruption for the primarily French administration, which fabricated incidents of sabotage and requested funds to buy off local chiefs that it claimed were responsible for it. Furthermore, the line was forced to avoid interfering with local communities and water sources, pushing it out into the desert. This meant that the railway company had to build aqueducts to supply its steam locomotives, an additional unplanned expense.

Even before reaching the Ethiopian border, it was clear the firm had serious financial problems. A group of British investors calling themselves the New Africa Company effectively took control of the firm over several years. They provided a new source of capital, and by 1901 had joined with the French investors to form the International Ethiopian Railway Trust and Construction Company, a holding company which controlled the railway and supplied it with further capital. The mixture of French and British interests proved volatile, as each group of investors stood for both national and commercial interests. Both governments grew interested in monopolizing Ethiopian trade and conspired to force the other into a minority position. The demands and threats of the two governments led Emperor Menelek in 1902 to forbid the extension of the railway line to Harar. French negotiations to resume work were blocked by Menelek's growing suspicion of French motives, and the line could not earn enough to pay back the company's debts with such a limited service. The signing of the Entente Cordiale in 1904 reopened the possibility of continued joint Anglo-French investment and development, but there was enough resistance to such proposals on both sides that no progress was made. The firm went formally bankrupt in 1906.

The portion completed ran from Djibouti to just short of Harar,[12] the principal entrepôt for commerce in southern Ethiopia.[9] The terminus evolved into the city of Dire Dawa, which grew to become larger than Harar itself. The first commercial service began in July 1901 from Djibouti to Dire Dawa.

Following the 1906 Tripartite Treaty between Italy, France, and Britain and the 1908 Klobukowski Treaty between France and Ethiopia, Menelek consented to further expansion of the railway. The new concession was granted to Menelek's personal physician, a black Guadeloupean named Dr. Vitalien, on 30 January 1908.[13] The assets of the former company were then transferred to a new firm, the Franco-Ethiopian Railway (Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Franco-Éthiopien[8]), which received a new concession to finish the line to Addis Ababa. After a year of wrangling with the previous financiers and their governments, construction began anew. By 1915 the line reached Akaki, only 23 kilometers from the capital, and two years later came all the way to Addis Ababa itself.

Operation (1917-1936)

After having reached Addis Ababa, construction of railways stopped in Ethiopia. The original plans included an extension of the railway from Addis Ababa to the Didessa River near Jimma, which would allow the railway to access traffic from the main coffee-producing areas of Ethiopia. However, that plan was scrapped and the railway was considered to be complete after reaching Addis Ababa. In 1929, the main train station in Addis Ababa, the Legehar train station ('La Gare'), was completed and put into operation.[14] In the 1930s, the railway carried 70% of all Ethiopian trade.[15]:95

Italian occupation and World War II (1936-1945)

Ethiopia's share in the railway was seized by the Italian government in the Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1936), but the Anglo-French company continued to operate during the Italian occupation. Steam trains of the Krupp type took approximately 36 hours to travel the full length of the line. Increased speeds were achieved by importing trains made by the Italian manufacturers Ansaldo and Breda, along with self-propelled cars from Fiat. Travel time decrease to 30 hours.[16]

The Italian "Addis Ababa Regulatory Plan of 1938" advocated the creation of three railway stations in the city of Addis Ababa to replace the Legehar train station, which would be demolished. The Italian occupiers also planned to build several new railways to link Ethiopia with their other East African colonies. The Addis Ababa–Dessie–Massaua Railway and the Gondar–Dessie–Assab Railway would reach Italian Eritrea, and the Addis Ababa–Dollo–Mogadishu Railway would reach Italian Somaliland. However, Italian setbacks in World War II forced the abandonment of these expansion projects. After British troops expelled the Italians in 1941 and restored Haile Selassie to the throne, the railway line was temporarily closed until 1944.

Post-World War II

In 1947, the Railroad Workers Syndicate was founded as one of the first labor unions in Ethiopia.[17] Although the Syndicate was mostly a mutual aid organisation, the government viewed strikes as insurrection. A strike in 1949 was brutally suppressed.[18]

In 1960–1963, the Franco-Ethiopian Railways conducted surveys to extend the line 310 kilometers from Adama to Dilla. Although the French government offered a loan in 1965, the project was never realised.[19]

Following the independence of Djibouti in 1977, the French share in the railway was transferred to the new nation. Around 1982, the railway was subsequently reorganized as the Ethio-Djibouti Railways (Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Djibouto-Éthiopien[8]).

Decline

After World War II, the railway began a long period of decline. Traffic on the railway dropped in half from 1953 to 1957, as road transport began to compete for cargo.[20] The Ogaden War of 1977–1978 dealt a further blow to the railway, as Somali troops invaded Ethiopia and captured the railway as far as Dire Dawa.[21] Portions of the railway were blown up in the war, and railway operations were again cut in half.[22] After the war ended, the railway continued to decline from a lack of maintenance and attacks from rebels such as the Ogaden Liberation Front.[23]

Both the lack of maintenance and an ambitious road construction program made rail transport increasingly non-competitive. In January 1985, the Awash rail disaster killed 429 passengers when their train derailed on the Awash River Bridge and fell into the gorge below. Railway service ended in 2008 between Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa,[24] but trains continued to run between Dire Dawa and Djibouti.

| Year | Freight (tonnes) | Passengers | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 450,000 | 1,400,000 | [25] |

| 1986 | 336,000 | 1,000,000 | [26] |

| 2002 | 207,000 | 501,000 | [26] |

Partial rehabilitation (2006-2014)

.jpg.webp)

The governments of Ethiopia and Djibouti pursued foreign aid to rehabilitate the railway. The European Commission prepared a grant of EUR 40 million in 2003 and raised it to EUR 50 million in 2006. An agreement was signed with the Italian consortium Consta on November 29, 2006, and work began in 2007 on sections of the line that deteriorated following the Ogaden War. The rehabilitation planned to reduce the cost of rail transport between Addis Ababa and Djibouti from $55 per tonne to $20 per tonne, compared to $30 per tonne for road transport.[25] Lightweight rails of 20–25 kg/m would be replaced with heavier 40 kg/m rails, effectively doubling the allowed axle load of the trains on the railway line to 17 tons per axle.[27] Almost half of the rails would be replaced, and along with 49 damaged steel bridges.[25]

.jpg.webp)

In 2006, the South African firm Comazar was chosen to receive a 25-year concession.[28] However, this plan was not executed, and in early 2008, it was announced that the railway was in negotiations with the Kuwaiti company Fouad Alghanim and Sons Group.[29] The EU-funded rehabilitation project stagnated, and only 5 km of tracks had been rehabilitated by 2009.[30] The Addis Ababa railway terminal, La Gare, was threatened with demolition in 2008 by a street project, but the building survived.[31] The tracks between Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa fell into total disrepair, and many of the rails were stolen and sold for scrap.[32]

Rail service between Dire Dawa and Djibouti City ended in August 2010.[33][32][34] However, the rehabilitation project resumed, and the tracks from Dire Dawa to the Djibouti border were returned to service in 2013.[33]

As of 2018, trains run on 213 km of rehabilitated line between Dire Dawa and Guelile. However, very few passengers use the train.[2] There are plans to restore 150 km of tracks from Dire Dawa to Mieso.[3]

Operating company

Ethio-Djibouti Railways also stands for the Ethio-Djibouti Railways Enterprise (French: Compagnie du Chemin de Fer Djibouto-Éthiopien (CFE)[8]), which was a bi-national railway company for the administration and operation of the Ethio-Djibouti Railway.

The Ethio-Djibouti Railways Enterprise was established in 1981 as the successor to the Franco– Ethiopian Railway, and it was jointly owned by the governments of Ethiopia and Djibouti.[35]

The company was headquartered in Addis Ababa; the ministers of the Djiboutian Ministry of Equipment and Transport and the Ethiopian Ministry of Transportation and Communications were the president and vice-president of the company. In 2010, the company ceased operations with Djibouti leaving, the Ethiopian part was taken over by the Ethiopian government.

The Ethio-Djibouti Railways Enterprise formally ceased to exist at the end of the year 2016, as the concession originally issued in 1894 by Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia wasn't renewed. All the properties of the company went back into the ownership of the Ethiopian state. The concession granted in 1894 came into force for 99 years after the official opening of the railway line in the year 1917, four years after the death of the Emperor.

See also

- Rail transport in Ethiopia

- Railway stations in Ethiopia

- Kunming–Haiphong railway - a similar French-designed meter-gauge railway in Asia

References

Notes

- "Chinese-built Ethiopia-Djibouti railway begins commercial operations". Xinhua. 1 January 2018.

- "The revival of the Ethiopia-Djibouti railway line". France24. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Enterprise to repair old Dire Dawa-Meiso railway line". Fana Broadcasting. 3 March 2018. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "The World Factbook". CIA.

- Michał Kozicki: "The history of railway in Ethiopia and its role in the economic and social development of this country", Studies of the Department of African Languages and Cultures 49 (2015), Adam Mickiewicz University; ISSN 0860-4649

- Belda, Pascal (2006). Ebizguide Ethiopia. MTH Multimedia S.L. pp. 180–81. ISBN 9788460796671.

CDE has over 187 steel bridges with spans varying from 4 to 141 meters. Gol du Harr, located at North-East of Dire Dawa, at Km 181, is the only tunnel along the rail track.

- Uhlig, Siegbert (2003). "Ilg, Alfred". Encyclopædia Æthiopica. Vol. 3. p. 120. ISBN 9783447056076.

- Crozet, Jean-Pierre. "The Franco-Ethiopian and Djibouto-Ethiopian Railway". Françoise Faulkner-Trine, trans. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. and "History". 2013. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 950.

- Uhlig, Siegbert (2003). "Le Roux, Robert Henri". Encyclopædia Æthiopica. Vol. 3. p. 551. ISBN 9783447056076.

- Negatu, Workneh (2004). Proceedings of the Workshop on Some Aspects of Rural Land Tenure in Ethiopia: Access, Use, and Transfer. IDR/AAU. p. 43.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95.

- Harrassowitz, Otto (2007). "Klobukowski Treaty". Encyclopædia Æthiopica. Vol. 3. ISBN 9783447056076.

- Liu, Xiaohong, Sharon. Abandoned train station redevelopment (Thesis). The University of Hong Kong Libraries. doi:10.5353/th_b4266457.

- Keller, Edmund J. (1988). Revolutionary Ethiopia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Ghosal, Vivek (2017-02-21). "High-Speed Rail Markets, Infrastructure Investments, and Manufacturing Capabilities". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2926108. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Local History in Ethiopia" (PDF). The Nordic Africa Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- Keller, Edmund J. (1988). Revolutionary Ethiopia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 147.

- "Dil Amba – Djibiet" (PDF). Local History in Ethiopia. The Nordic Africa Institute. 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2011.Kenney, Nathaniel T. (1965). "Ethiopian Adventure". National Geographic Magazine (127).

- Bergqvist, Rickard (2016). Dry Ports – A Global Perspective. Routledge. p. 93. ISBN 9781317147671.

- Cooper, Tom (2014). Wings over Ogaden: The Ethiopian–Somali war, 1978–1979. Helion. p. 56. ISBN 9781909982383.

- "Ethiopia". Middle East Economic Digest. 22: 11. 1978.

The railway line was cut frequently during the Ogaden war, but has been operating at 50 per cent capacity since July.

- "Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway". Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Scarecrow Press. 11 April 2013. p. 23. ISBN 9780810874572.

- Vaughan, Jenny (March 10, 2013). "China's Latest Ethiopian Railway Project Shows Their Growing Global Influence". Agence France Presse.

While the economic benefits of the train – which will be used for both freight and passenger transport, replacing slow and costly truck transport – is widely recognised, some lament the seemingly inevitable death of the historic French-built diesel-powered train, which went out of service in 2008 after years of neglect.

- "Briefing Memorandum: Djibouti-Ethiopia Railway" (PDF). ICA. 4 December 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- "OECD - Ethiopia GD 06" (PDF). OECD. 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

The rail corridor, which dates from 1917, has lost competitiveness, especially since Ethiopia has begun to improve its road network. The railway’s freight volume fell from a high of 336 000 tonnes in 1986 to a low of 207 000 tonnes in 2002, and the number of passengers fell from 1 million in 1986 to 501 000 in 2002.

- Continental Railway Journal 161 (2010), S. 112.

- "South African firm wins bid to administer Ethio-Djibouti railway". Hiiran Online.

- "No concession at Ethio-Djibouti Railway". Railway Gazette International. September 2007.

- Foch, Arthur (March 2011). "The paradox of the Djibouti-Ethiopia railway concession failure" (PDF). Private Sector & Development (9): 18.

For example, in 2009 only five kilometres of track had been rehabilitated. ... The two States gradually abandoned the CDE, which by 2011 had ceased all activities.

- "Historic Addis Ababa railway station under threat". addis-ababa.wantedinafrica.com. 28 May 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- "Ethiopia: Historic Ethio-Djibouti Railway Track Worth Br20 Million Stolen". The Reporter Ethiopia. 2 August 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

According to Addis, the individuals are also stealing the railway line that lies between Adama and Wolenchiti towns. Addis said that the culprits sell the steel structure to foundries established by Chinese citizens in Adama town and near Koka. According to Addis, so far railway lines worth 20 million birr have been stolen. [...] The Ethio-Djibouti Railway Enterprise ceased operations in 2010. “There is no adequate budget to hire people to guard the railway line, stations and other properties of the enterprise"

- "Dire Dawa – Djibouti railway restarts operation". Hornaffairs.com. 7 September 2013.

- April 27, 2015. "Train travel in Ethiopia & Djibouti". The Man in Seat 61. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015.

Most of the guide books have the info’ on the train completely wrong, most of them still saying the train departs Addis Ababa but this has not happened for over two years. They also say the train does not operate at night because of the chances of attacks, but this is also wrong as the train I caught on Sunday 20-12-2009 departed at 10.30am (over a day late) and arrived Djibouti at 05.30am the next. I spent over 18 hours in the cab!!!!

- Belda, Pascal (2006). Ebizguide Ethiopia. MTH Multimedia S.L. p. 180. ISBN 9788460796671.

Soon after the independence of Djibouti, the government of Ethiopia and Djibouti signed a new treaty on March 1981, for 50 years on equal parity ownership under "chemin de Fer Djibouto–Ethiopien" name.

Further reading

- Brisse, André (1901). "Djibouti et le chemin de fer du Harar". Annales de géographie (in French). 10 – via Persee.fr.

- Fontaine, Hugues (2012). Un Train en Afrique. African Train (in English and French). traduction by Yves-Marie Stranger; postface by Jean-Christophe Belliard; photographers Matthieu Germain Lambert and Pierre Javelot (bilingue français / anglais ed.). Addis Abeba: Centre Français des Études Éthiopiennes / Shama Books. ISBN 978-99944-867-1-7.

- Killion, Tom C. (1992). "Railroad Workers and the Ethiopian Imperial State: The Politics of Workers' Organization on the Franco-Ethiopian Railroad, 1919–1959". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 25 (3): 583–605. doi:10.2307/219026. JSTOR 219026.

- Robinson, Neil (2009). World Rail Atlas and Historical Summary. Volume 7: North, East and Central Africa. Barnsley, UK: World Rail Atlas Ltd. ISBN 978-954-92184-3-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chemin de fer djibouto-éthiopien. |