Italy–Spain relations

Italy–Spain relations refers to interstate relations between Italy and Spain. Both countries established diplomatic relations after the unification of Italy. Relations between Italy and Spain have remained strong and affable for centuries owing to various political, cultural, and historical connections between the two nations.

| |

Italy |

Spain |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Italy, Madrid | Embassy of Spain, Rome |

Precedents

In 218 BC the Romans invaded the Iberian peninsula, which later became the Roman province of Hispania. The Romans introduced the Latin language, the ancestor of both modern-day Spanish and Italian. The Iberian peninsula remained under Roman rule for over 600 years, until the collapse of the Western-Roman Empire.

In the Early modern period, until the 18th century, southern and insular Italy came under Spanish control, having been previously a domain of the Crown of Aragon.

Establishment of diplomatic relations

After the proclamation of Victor Emmanuel II as King of Italy in 1861 Spain failed to initially recognise the country, still considering Victor Emmanuel as the "Sardinian King".[1] The recognition was met by the opposition of Queen Isabella II of Spain, influenced by the stance of Pope Pius IX.[2] Once Leopoldo O'Donnell overcame the opposition of the Queen, Spain finally recognised the Kingdom of Italy on 15 July 1865.[3] Soon later, in 1870, following the dethronement of Isabella II at the 1868 Glorious Revolution, the second son of Victor Emmanuel II, Amadeo, was elected King of Spain, reigning from 1871 until his abdication in 1873.

Interwar period

Despite some incipient attempts to promote further understanding between the two countries, immediately after the end of World War I there were still issues restraining further Italian-Spanish engagement in Spain, including a sector of public opinion showing aversion towards Italy (a prominent example being Austria-born Queen Mother Maria Christina).[4]

Once dictators Benito Mussolini (1922) and Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923) got to power, conditions for closer relations became more clear, with the notion of a rapprochement to Italy becoming more interesting to the Spanish Government policy, particularly in terms of the profit those improved relations could deliver to Spain vis-à-vis the Tangier question (with France conversely antagonising Spain on this issue).[4] For Italy, the installment of the dictatorship in Spain offered a prospect for greater cultural ascendancy over a country with a government now widely interested in the reforms carried out in Italy.[5] The diplomatic relations between the two countries often became entangled in the wider triangular diplomacy that also included France. While showing a will for friendship and rapprochement, the "Treaty for Conciliation and Arbitration" signed in August 1926 between the two countries delivered limited substance in practical terms, compared to the expectations at the starting point of the Primorriverista dictatorship.[6] A diplomatic "honeymoon" between the two regimes followed the signing of the treaty, nonetheless.[7]

Spanish civil war

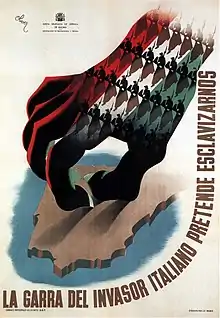

Meanwhile, fascism emerged in Spain, including its charismatic leader, José Antonio Primo de Rivera (1903–36), who believed that Italian Fascism, as personified by Mussolini, was the perfect model. After his execution by Spanish republican forces in 1936, Francisco Franco became the leader of the Falange Party, as well as chief of state and commander of the armed forces. He was not a charismatic fascist leader in the manner of Primo de Rivera or Mussolini, but he did come to personify the mission of the Falange. Franco did not allow the Falange to control his actions—rather he controlled it until his death in 1975.[8] In 1936 Mussolini intervened on the side of Francisco Franco and the Spanish Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War, helping Franco win. The Corps of Volunteer Troops, a fascist expeditionary force from Italy, brought in about 50,000 Italians troops.

World War II

During World War II, 1939 to 1943, Spanish-Italian ties were close. Though Italy fought alongside Germany during the war, Spain was engulfed in a civil war and remained neutral. In February 1941, the meeting between Mussolini and Franco in Bordighera took place; during the meeting the Duce asked Franco to join the Axis.[9] After Mussolini fell in 1943, Italy was ripped apart in its own civil war, and Spain stayed away;[10] From 1943 onwards, both the Kingdom of Italy and the Italian Social Republic aimed to maintain good diplomatic relations with Francoist Spain; those attempts for rapprochement were however aborted by Spain in order to ensue the balance in its relation with both countries as well as with the rest of belligerent powers.[11]

Common membership

Both countries are full members of NATO, the Union for the Mediterranean, European Union, and the Eurozone.

Resident diplomatic missions

- Italy has an embassy in Madrid and a consulate-general in Barcelona.

- Spain has an embassy in Rome and consulates-general in Genova, Milan and Naples.

_01b.jpg.webp) Embassy of Italy in Madrid

Embassy of Italy in Madrid Consulate-General of Italy in Barcelona

Consulate-General of Italy in Barcelona Embassy of Spain in Rome

Embassy of Spain in Rome

See also

References

- López Vega & Martínez Neira 2011, p. 96.

- López Vega & Martínez Neira 2011, pp. 96; 98.

- López Vega & Martínez Neira 2011, p. 99.

- Sueiro Seoane 1987, pp. 185–186.

- Domínguez Méndez 2013, p. 238.

- Tusell & Sanz 1982, p. 443–445.

- Tusell & Saz 1982, p. 444.

- Stanley G. Payne, "Franco, the Spanish Falange and the Institutionalisation of Mission." Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 7.2 (2006): 191-201.

- Payne 1998, p. 110.

- Stanley G. Payne, "Fascist Italy and Spain, 1922–45." Mediterranean Historical Review 13.1-2 (1998): 99-115. online

- Hierro Lecea 2015, p. 17.

Bibliography

- Domínguez Méndez, Rubén (2013). "Francia en el horizonte. La política de aproximación italiana a la España de Primo de Rivera a través del campo cultural". Memoria y Civilización. Pamplona: University of Navarre (16): 237–265.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hierro Lecea, Pablo del (2015). Spanish-Italian Relations and the Influence of the Major Powers, 1943-1957. Security, Conflict and Cooperation in the Contemporary World. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-49654-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- López Vega, Antonio; Martínez Neira, Manuel (2011). "España y la(s) cuestión(es) de Italia" (PDF). Giornale di Storia Costituzionale (22): 96.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Payne, Stanley G. (1998). "Fascist Italy and Spain, 1922–45" (PDF). Mediterranean Historical Review. 13 (1–2): 99–115. doi:10.1080/09518969808569738. ISSN 0951-8967.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sueiro Seoane, Susana (1987). "La política mediterránea de Primo de Rivera: el triángulo Hispano-ltalo-Francés" (PDF). Revista de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (1): 183–223.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tusell, Javier; Saz, Ismael (1982). "Mussolini y Primo de Rivera: las relaciones políticas y económicas de dos dictaturas mediterráneas". Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. CLXXIX (III): 413–484.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.svg.png.webp)